Post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents

The posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in children and adolescents is a serious mental disorder . Research shows that even toddlers and preschoolers can develop PTSD. PTSD in children and adolescents has a number of characteristics compared to PTSD in adults .

Colloquially, a lot of situations, such as B. Called divorce "traumatic". However, these usually do not lead to the characteristic symptoms of PTSD. The scientific term trauma is more narrowly defined in the diagnostic classification systems of mental disorders ( DSM-IV and ICD-10 ): It is an event in which the person concerned experiences a situation directly or indirectly with great fear and horror, which is a threat the physical integrity of himself or another person. Examples are psychological terror ( bullying ), sexual and physical violence , accidents or natural disasters. In children and adolescents, “the verbal communication of such an event also seems to be able to trigger PTSD, e. B. the news or photographs of the violent death of a family member ”.

Following a traumatic event, in the case of PTSD symptoms of reliving (e.g. intrusions and flashbacks ), avoidance and autonomic overexcitation must be present. The basic dimensions of the listed symptoms are shown in Table 1. They make it clear that PTSD in children is age-specific and is largely determined by the level of their cognitive , affective and social development.

Traumatic events are also divided into type 1 trauma, ie short-term traumatic events and type 2 trauma, ie long-lasting, repetitive traumatic events. Furthermore, a distinction is often made between catastrophes and man-made disaster, whereby the long-term and man-made traumatic events have more serious effects on mental health and can go well beyond the symptoms listed in Table 1 (see also: trauma (psychology): event factors ).

Case studies

Two case studies are given to illustrate the symptoms.

| Case study 1: Robert, 9 years old, lives with a foster family. At the age of six he was placed by the youth welfare office together with his brother with his uncle and aunt, as he was very often abused by his mother. So she kicked him, hit him with her fists and hit his head against the wall. In addition, she locked him and his brother in his room for many hours and went outside. During this time, he urinated and pooped on the floor of the room. If he was alone at night, he was afraid during these phases. In his early childhood, he watched his mother being abused by his father. He has no concrete memory of that time. Before he was housed with his uncle and his aunt, he spent a few weeks in an assisted living group for children. Today he remembers his own abusive situations very often. He behaves restlessly, suffers from severe lack of concentration and often reacts aggressively. Often he becomes conspicuous by beating other children for no apparent reason and getting into quarrels with them, like with his younger brother, whom he often beats. He also often gets into arguments with his teachers. His linguistic and intellectual abilities are far below his non-verbal abilities. At school he gets bad grades, so the class teacher has already considered that he should repeat a class. However, a special educational need has not yet been identified. At night he often suffers from anxiety and feels threatened. Occasionally he also has nightmares. He suffers from unspecific sleep disorders, which include problems falling asleep, staying asleep and waking up too early. The school psychology service advises foster parents to have him tested for attention deficit / hyperactivity disorder. |

| Case study 2: Peter, 10 years old, is a bright boy who likes to play soccer and swim. He and his friend go swimming at a lake for a weekend. While swimming in deeper water, Peter's friend suddenly panic. He clings to Peter, submerges him and never lets go. Peter can't breathe anymore, at the last second he pushes his friend away.

The two children react very differently to the event. The friend is fine, but Peter now avoids anything that has to do with water, as he associates the feeling of suffocation with water. He screams and defends himself when he is supposed to shower or bathe in the tub. He doesn't want to go to swimming lessons at school, the lessons trigger anxiety in him and he usually fakes a headache so that he doesn't have to go. He does not speak to his parents when they ask him about his changed behavior. After the mother found out about the incident at the lake, she turned to the sports teacher with whom Peter had swimming lessons at school. This advises the mother to an appointment with a psychologist. |

Diagnostic criteria for PTSD in children and adolescents

Preliminary remarks:

(1) “The younger a person is, the greater the consequences of trauma” (Scheeringa et al. , 2003; Steil, 2003, quoted in Arnold, 2010). (2) The PTSD criteria were developed on the basis of adult symptoms. However, they only partially reflect the reactions in childhood and adolescence. Especially in the area of DSM criteria C (avoidance) and D ( hyperarousal ), children and adolescents show symptoms similar to adults (Arnold, 2010). In the DSM-IV-TR, special features in children are explicitly stated in criteria A and B. (3) Some authors suggest that fewer symptoms in children than in adults should be sufficient for a diagnosis: One symptom for criterion B, one symptom for criterion C and two symptoms for criterion D (see Scheeringa et al. , 2003; Simons & Herpertz-Dahlmann, 2008). (4) The most common symptoms in traumatized children between the ages of 7 and 14 are “avoidance of thoughts, feelings and talking about the trauma”, “inability to remember all important aspects of the traumatic event”, “stressful memories” and “stressful Dreams "called. (Carrion et al. , Quoted in Simons & Herpertz-Dahlmann, 2008).

| Symptoms of PTSD according to DSM-IV | Possible symptoms in children and adolescents and differences from the adult criteria |

|---|---|

|

A. Initial response to traumatic event

The individual was faced with a traumatic event in which the following two criteria were met:

|

Re A1: Difficult with preschool children, as the reactions are primarily conveyed through the reactions of caregivers (Rosner & Hagl, 2008).

Regarding A2: Dissolved or agitated behavior (DSM-IV-TR, Saß et al. , 2003), e.g. screaming, whimpering, freezing or undirected urge to move, trembling, fearful facial expression. |

|

B. Reliving and memories

The traumatic event is persistently relived in at least one of the following ways:

|

For younger children: games in which themes or aspects of trauma are repeatedly expressed (DSM-IV-TR); very frightening dreams related to trauma or with increasing frequency without recognizable content (DSM-IV-TR; Scheeringa et al. , 2003); screams in sleep at night; trauma-specific new productions in smaller children (DSM-IV-TR, 2003); dissociative episodes (Scheeringa et al ., 1995); Psychological stress when confronted with cues (Scheeringa et al. , 1995); clingy behavior (Steil & Rosner, 2009). |

|

C. Avoidance

Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma or a flattening of general responsiveness (absent prior to the trauma). At least three of the following symptoms are present:

|

Difficult with children due to outside regulation of everyday life; Scheeringa et al. (2003) propose “ flattening of responsiveness ” as the category .

Avoid anything that might remind you of the experience (including talking about it) (Scheeringa et al. , 2003); Withdrawal from parents and / or playmates (Scheeringa et al. , 1995); emotional numbness ; Flattening of feelings; Lack of emotion (Steil & Rosner, 2009); seemingly indifferent and indifferent to the environment; restricted gaming behavior (Scheeringa et al ., 2003); decreased interest in previously significant things (Steil & Rosner, 2009); Feelings of alienation; Automutilation (Steil & Rosner, 2009); altered dysregulated eating behavior (Arnold, 2010); Perception of a shortened future (doesn't think you'll ever grow up or finish school; DSM-IV-TR); excessive concern for family members (Steil & Rosner, 2009); Loss of skills already acquired (especially language, toilet training; Scheeringa et al ., 1995); regressive behavior (thumb sucking, secondary enuresis or encopresis , speaking like a small child, fear of being alone; Steil & Rosner, 2009). |

|

D. Hyperarousal

Persistent symptoms of increased arousals (absent prior to trauma). At least two of the following symptoms are present:

|

Increased autonomic arousal; Nocturnal anxiety (Scheeringa et al. , 1995); Difficulties falling asleep and staying asleep (Scheeringa et al. , 2003), concentration disorders (Scheeringa et al. , 2003); Memory disorders; Deterioration in school performance (Steil & Rosner, 2009); Irritability, outbursts of anger (Steil & Rosner, 2009), fights; excessive vigilance (Scheeringa et al. , 2003;); Jumpiness (Scheeringa et al. , 2003); reacts for no apparent external reason, destroys e.g. B. Objects, suddenly starts crying or screaming; somatic disorders (stomach pain, headache, DSM-IV-TR); increased susceptibility to infection (Arnold, 2010). |

| E. The disorder (symptoms under criteria B, C and D) lasts longer than 1 month. | Scheeringa et al. (2003) suggest an additional category of “ new fears and aggression ” for preschool children : new violent aggressive reactions; newly emerging separation fears (e.g. avoiding kindergarten); Fear of going to the bathroom alone; Fear in the dark; Fear of trauma-related things or situations. |

| F. The disorder causes disease or impairment in a clinically meaningful manner in social, professional or other important functional areas. |

Table 1: Symptoms of PTSD in children and adolescents according to DSM-IV

A new disorder category is currently being discussed as a proposal for the DSM-V , which should in particular capture the reactions to multiple interpersonal trauma, possibly in combination with neglect, the development-related trauma-related disorder. The criteria for this developmental trauma disorder in complex traumatized children according to van der Kolk et al. (2009) contains Box 1.

|

A: Event Criterion: Traumatic Experience and Neglect

A1: Multiple or chronic interpersonal trauma (direct or indirect) A2: Loss of protective caregivers as a result of changes, repeated separation from caregivers, or severe and persistent emotional abuse B: Affective and physiological dysregulation (at least two criteria) B1: Inability to change extreme emotional states, endure them and calm down on their own (fear, anger, shame) B2: Difficulties regulating body functions and sensory perceptions (sleeping, eating, over-sensitivity to touch, noise, etc.) B3: Decreased awareness / dissociation of perception, emotions and physical states B4: Impaired ability to describe one's own emotions and physical conditions C: Dysregulation of attention and behavior (at least three criteria) C1: Excessive preoccupation with threats or insufficient awareness of them (incorrect assessment of security and danger) C2: Limited ability to protect yourself (risk-seeking behavior) C3: Inappropriate methods of self-soothing C4: Habitual or reactive self-harm C5: Inability to develop or maintain goal-oriented behavior D: Difficulties in self-regulation and building relationships (at least three criteria) D1: Intensive preoccupation with the safety of a caregiver or other loved one; Difficulty enduring breakups D2: Negative self-image, especially helplessness, worthlessness, a feeling of damage, lack of self-efficacy expectations D3: Suspicion, inadequate reciprocal behavior towards others D4: Reactive physical or verbal aggression D5: Inappropriate attempts to establish intimate relationships; Excessive trust in largely unknown adults or peers D6: Inability to have adequate empathy E: Symptoms from the post-traumatic spectrum At least one symptom from two of the PTSD symptom clusters Q: Duration of at least 6 months G: Functional impairments in at least one important area of life |

Box 1: Criteria for developmental trauma-related disorder in complex traumatized children according to van der Kolk et al. (2009)

Pathogenesis

Risk factors

There are a number of factors that increase the likelihood of post-traumatic stress disorder or are protective factors . Risk factors can be divided into pre-traumatic (factors with which a person enters the traumatic situation), peritraumatic (characteristics of the event and psychological processes in this situation) and post-traumatic (factors that have an effect on the situation). Among the pre-traumatic factors, younger age, female gender, minority status , low socio-economic status , pre-traumatic psychological morbidity (mental disorders already existing before the traumatic event), pre-traumatization, family structure, functional level, poor visual memory play a role (De Bellis et al. , 2010), possibly genetic predispositions ( cortisol or catechol-O-methyltransferase) (Kolassa et al. , 2010) and substance abuse (Kingston & Raghavan, 2009) a role. The peritraumatic factors include stressor severity, perceived danger to life, death and injury to known people, loss of resources, personal injury, circumstances of the event, emotional reaction, parenting behavior, and admission to a pediatric intensive care unit (Bronner et al ., 2008). Relevant post-traumatic factors are the acute stress reaction (ABR), psychopathology , lack of social support, dysfunctional coping strategies , PTSD of the mother (Yehuda et al. , 2008), family factors, high overprotection of the parents (Bokszczanin, 2008), frequent changes of residence and other stressful ones Life events. The factors most associated with PTSD are the peritraumatic factors stressor severity, perceived danger to life and loss of resources, and the post-traumatic factors acute stress reaction, psychopathology, lack of social support and other stressful life events (Kultalahti & Rosner, 2008). Pre-traumatic mental illness is also closely related to the development of PTSD (Kultalahti & Rosner, 2008). Table 2 provides an overview of the possible risk factors for PTSD.

| Pre-traumatic factors |

|

| Peritraumatic Factors |

|

| Post-traumatic factors |

|

Table 2: Possible risk factors for PTSD in children and adolescents

PTSD models

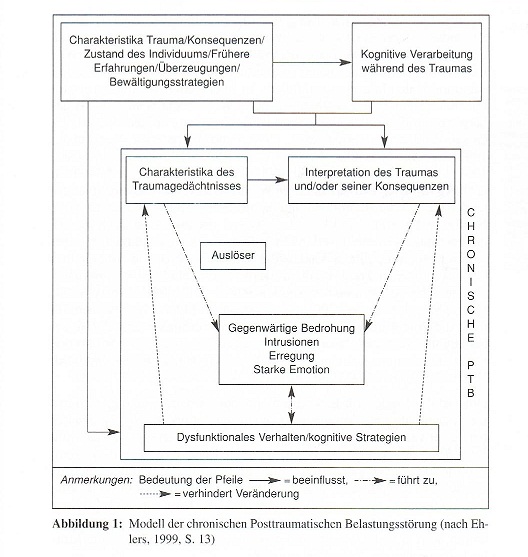

A number of models have been developed to explain PTSD. They must be able to explain (a) the symptoms (b) recovery and healing and (c) individual differences (Dalgleish, 2004, quoted in Steil & Rosner, 2009). An adaptable model of PTSD for children and adolescents is the cognitive model of PTSD according to Ehlers and Clark (2000).

Ehlers and Clark model of PTSD

The PTSD model is a cognitive model. According to Ehlers and Clark (1999, quoted from Ehlers, 1999), two different factors are necessary for the development of PTSD. On the one hand, the interpretation of the traumatic event, on the other hand, the characteristics of memory for traumatic memories and their connection to episodic and autobiographical memory play a role.

Ehlers and Clark (1999, quoted from Ehlers, 1999) assume that PTSD patients have difficulty willingly remembering the traumatic event that intrusive experience is predominantly sensory and not cognitive.

Figure 1 shows the model developed by Ehlers and Clark (1999, quoted from Ehlers, 1999). The authors state that people will only develop PTSD if they process a traumatic event in a way that they perceive to be experiencing a current threat.

Diagnosis

Special features of the PTSD diagnosis in children and adolescents

In view of the possible differences in PTSD symptoms as well as different requirements, a diagnostic procedure that takes this into account is indicated.

The diagnosis must take into account both the child's cognitive and linguistic level of development. These include B. Aspects of autobiographical memory and increased suggestibility in children (Cossins, 2010). For this reason, various sources of information should be consulted; In addition to the child's parents, this can also include carers or teachers.

With regard to the level of linguistic development, it should be taken into account that younger children also communicate in other ways, e.g. B. through drawing or playing behavior (Steil & Rosner, 2009). Due to the child-specific symptoms, it is necessary to use appropriate diagnostic instruments (interviews, questionnaires). As a rule, 2–5 sessions are required for a detailed diagnosis (Steil & Rosner, 2009). It serves as the basis for individually tailored therapy planning.

anamnese

At the beginning of the diagnosis there is an initial exploratory discussion, which includes the current and previous psychiatric symptoms of the child and parents, medical anamnesis , characteristics and circumstances of the traumatic event as well as resources and risk factors on the part of the child. This should be done separately for the child and caregiver (Steil & Rosner, 2009). Both perspectives should be taken into account because children mainly report internalizing problems (e.g. feelings of guilt and shame , fears , depressive moods ), while adults report more externalizing aspects (e.g. defiance and aggressive behavior, hyperactivity ) (Kolko & Kazdin, 1993) and generally tend to underestimate the child's symptoms (Ceballo, 2001).

Instrumental recording of the type and severity of the disorder

Diagnostics in preschool children

Since self-reports can only be regarded as reliable to a limited extent for children under 5 to 6 years of age (Cossins, 2010), the focus of diagnostics in this age range is on interviewing caregivers. Dehon and Scheeringa (2006) refer to the possibility of a diagnostic statement using a specific selection of 15 questions from the Child Behavior Checklist 1½ - 5 years (CBCL 1½ - 5 years; German Child Behavior Checklist work group, 2002). However, this should be interpreted with caution, since the CBCL rather records general psychological stress, but not specifically PTSD symptoms. An interview procedure translated into German is available for diagnosing PTSD in infants and young children (Graf, Irblich & Landolt, 2008).

Diagnostics in children over 6 years of age

Interview and questionnaire procedures exist for diagnosis. In general, (structured) interviews are preferable, as the child's cognitive and linguistic level can be addressed individually. Openly formulated questions reduce the risk of suggestions and thus increase the probability of unadulterated information being obtained (Cossins, 2010).

The interviews on stress disorders (IBS-KJ; Steil & Füchsel, 2006) are considered the gold standard for diagnosing 7 to 16 year olds. This procedure is the German translation of the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for Children and Adolescents (CAPS-CA; Nader, Blake & Kriegler, 1994). In addition to the type of disorder ( acute stress disorder (ABS), PTSD) according to criteria from both ICD-10 and DSM-IV , the frequency and intensity of the individual symptoms are recorded. Advantages of the procedure are the ease of understanding through child-friendly formulation and the use of visual analog scales. Standard values are available for the procedure and the test quality is considered to be assured (Steil & Rosner, 2009).

Other common methods are the UCLA-PTSD-RI (The University of California at Los Angeles Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index; Steinberg, Brymer, Decker & Pynoos, 2004), which can be used as an interview and questionnaire, as well as the pure questionnaire method Children's Impact of Events Scale (Dyregrov, Kuterovac & Barath, 1996), Child PTSD Symptom Scale (Foa, Johnson, Feeny & Treadwell, 2001; no German translation available) and the checklist for acute stress disorder (CAB; Früh, Kultalahti & Rosner, 2007; especially for the diagnosis of acute stress reactions). The test quality of the German-language versions has not been empirically verified in all cases (Steil & Rosner, 2009).

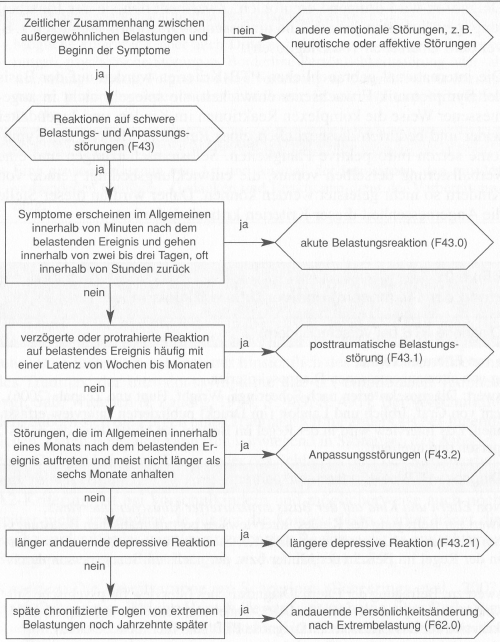

Differential diagnosis

A careful differential diagnosis is of central importance because the appearance of PTSD resembles other mental disorders in many ways.

Avoidance symptoms can also be found in the context of affective and anxiety disorders and overexcitation as hyperkinetic symptoms of attention deficit / hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Anomalies from the area of reliving could be misinterpreted as an expression of a psychotic disorder (Cohen et al. , 2010). Differentiation from the clinical picture of complicated grief , as well as borderline personality disorder , adjustment disorder and eating disorders may also be indicated (Steil & Rosner, 2009).

The German Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy suggests a differential diagnostic approach as shown in Figure 2.

Prevalence

The frequency of experiencing a traumatic (and thus potentially PTSD-triggering) event varies from region to region (cf. Darves-Bornoz et al. , 2008). This can be explained by differences in the occurrence of natural disasters, war events and the general incidence of violence in society.

Depending on the definition criteria of the event, the incidence in 13 to 16 year olds can rise to up to 90% in countries not affected by war if negative life events such as divorce or abortion are included in the statistics (Petersen, Elklit & Olesen, 2010 ). The likelihood of PTSD as a result of a traumatic event also depends on gender - girls are more likely to develop PTSD than boys (Gavranidou & Rosner, 2003) - and the type of event.

Table 3 provides an overview of epidemiological studies on PTSD in children and adolescents (according to DSM-IV criteria). Attention should be paid to the sometimes strongly varying prevalences , which can be attributed to the mentioned differences in the definition criteria of a traumatic event and other peculiarities of the respective studies.

| Study and land | Age | Prevalence of a Traumatic Event | Lifetime prevalence of PTSD | Number of participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essau et al . (2000) Germany | 12-17 years |

18.4% female 28.5% male |

1.6% total 1.4% male 1.8% female |

1035 |

| Perkonigg et al . (2000) Germany | 14–24 years |

17% total 18.6% male 15.5% female |

1.3% total 0.4% male 2.2% female |

3021 |

| Petersen et al . (2010)

Faroe Islands |

14.2

Years |

90% total 89% male 94% female |

20% total | 687 |

| Domanskaité-Gota, et al.

(2009) Lithuania |

15.1

Years |

80.2% total 80.7% male 79.8 female |

6.1% total | 183 |

| Copeland et al. (2007) USA | 9-16

Years |

68.2% total 67.9% male 68.4% female |

0.4% total 0.1% male 0.7% female |

1420 |

Table 3: Prevalence studies on traumatic events and PTSD in childhood and adolescence

A study with young children between 2 and 10 years by Meiser-Stedman et al. (2008), using alternative criteria of the DSM-IV for children, showed frequencies of 11.5% after traumatic traffic accidents. Therefore, if one assumes that the DSM-IV criteria, which are presumably too narrowly defined, partially exclude affected children and adolescents from the diagnosis, it can be assumed that PTSD actually occurs more frequently. This makes PTSD a common disease in children and adolescents compared to other mental disorders (Steil & Rosner, 2009).

course

An acute stress reaction (according to DSM-IV, corresponding in ICD-10: F43.0 acute stress reaction ) can occur within the first four weeks after a traumatic event . An acute stress reaction, however, has only a moderate prognostic connection with PTSD and is therefore still controversial as a predictor (Früh, Kultalahti, Röthlein & Rosner, 2008). PTSD can be diagnosed four weeks after the traumatic event. If symptoms start six months or later, it is called delayed-onset PTSD; this affects about 10% of the cases (Yule et al ., 2000).

The risk of developing PTSD is lower when using mental health care. Without treatment, the likelihood of developing PTSD or depression after a traumatic event is four times higher (Jia et al ., 2010).

Basically, one must assume a high risk of chronicity in PTSD: In 30% of the adolescents examined with a diagnosed PTSD, Yule et al. (2000) an improvement in the subclinical area one year after a ship accident. However, 34% of those affected still showed the full picture of PTSD several years after the accident. Perkonigg et al. (2006) report, as a result of a four-year long-term study, a risk of chronification of 42.4% in 14 to 17 year olds. Landolt et al. (2003) found no significant symptom changes within one year in a course analysis of untreated children with PTSD. The proportion of diagnoses even tended to increase.

Comorbidity

There are various research results regarding the frequency of comorbidities . In addition to methodological reasons, this is mainly due to differences in the age of occurrence, the course and the time sequence of the primary and secondary disorder (Essau, Conradt & Petermann, 1999).

Reported comorbidities of PTSD in childhood and adolescence are ADHD , affective disorders , anxiety disorders , somatoform disorders , suicidal behavior, and difficulties coping with everyday life (Essau, Conradt & Petermann, 1999).

Regardless of the specific diagnosis, Abram et al. (2007) found at least one comorbid disorder in 93% of the male adolescent prisoners they examined with PTSD. Two or more comorbidities were diagnosed in 54%. He found depression rates of 17%, 38% of the subjects had anxiety disorders, 43% of the subjects had ADHD and 79% of the subjects with substance abuse. The rates for female offenders varied: 24% were depressed, 27% had anxiety disorders, 40% ADHD and 63% substance use disorders (Abram et al ., 2007).

Slightly different frequencies are found in preschool children. Scheeringa and Zeanah report a general comorbidity rate of 88.6% in the presence of PTSD - the most common of these were oppositional defiance and anxiety disorders (Scheeringa & Zeanah, 2008).

PTSD is often associated with an increased rate of physical illness. In an overview study, Rohleder and Karl (2006) report particularly on cardiovascular diseases , autoimmune diseases and chronic pain (see also Boscarino, 2004). However, there is little empirical evidence on this topic for patients in childhood and adolescence .

Developmental trauma-related disorders

After intensive examination of trauma apsyschology in childhood and adolescence, Bessel van der Kolk came to the conclusion that children who were (or are still) exposed to traumatic experiences in their childhood have various other diseases in addition to PTSD. These can be both physical and psychological in nature. He sees changes in neurobiological developments caused by extreme stress as the cause of this (cf. Krüger & Reddemann 2007, p. 66).

Some of these developmental trauma-related disorders are (cf. Krüger & Reddemann 2007, p. 70):

- Exposure & change in the subjective quality of experience (e.g. with regard to fear , feelings of shame or defeat)

- Repeated patterns of dysregulation in response to trauma triggers (e.g., self-attribution, self-hatred, or states of confusion)

- Persistently changed attributions and expectations (e.g. mistrust of protective caregivers, negative self-image or a lack of conscience )

- Impairment of social and other functions (e.g. at school, work or leisure)

Various factors determine the intensity of the effects of trauma on the subsequent development of children. These are listed below (cf. Streck-Fischer 2006, p. 2):

- Level of development at the time of trauma

- Previous conditions of development

- Resources that the child can fall back on

- Integration into a stable social network

- Availability of a person of trust

Interventions in traumatized children and adolescents

There are currently many different interventions (at least 200 according to Streeck-Fischer (2007)) that are used in trauma therapy in children. However, so far only very few interventions have been scientifically examined with regard to their suitability and effectiveness for children and adolescents.

Children and adolescents who have just experienced a traumatic event should first receive medical and then psychosocial care in the acute situation as part of a crisis intervention . The main aim of psychosocial care is to restore normality by satisfying basic needs such as hunger, thirst and tiredness and creating a stable sense of security (e.g. through contact with caregivers, familiar surroundings, familiar daily routines) (Steil & Rosner, 2009).

Another possible crisis intervention in acute care is individual session debriefing (Psychological Debriefing (Dyregrov, 1979), Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (Mitchell, 1983)). This is not to be recommended, as no reliable evidence for the effectiveness of single session debriefing in children has been found (NICE, 2005; Stallard, 2006).

Children and adolescents who have experienced a traumatic event need further intervention after the crisis intervention if they develop a mental disorder, in particular ABS or PTSD. According to current research results, trauma-focused therapy approaches are most effective for this. Trauma-focused means that the traumatic experiences of the child are placed at the center of therapy and explicitly addressed (exposure). Currently, trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) are considered the best-studied methods (AACAP, 2010; NICE, 2005).

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy consists of the following components:

- Psychoeducation (providing general information on possible reactions to traumatic events)

- Stress management (e.g. learning relaxation and breathing techniques)

- Exposure (confrontation with trauma-specific memories and situations that are avoided due to the high aversive character)

- Cognitive therapy (identification and modification of unhelpful thoughts and feelings)

Before starting therapeutic work on trauma, children's resources need to be strengthened. Parents and other caregivers are an essential part of these resources. According to the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP), parents should be involved in therapy as supporters of positive change; Likewise, educators in day care centers, teachers and doctors of the child. The common goal is to promote the ability to function, resilience and further development of the child (not just a reduction in symptoms) (AACAP, 2010). A well-proven trauma-focused therapy manual that meets the requirements of the AACAP is, for example, trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy based on the manual by Cohen, Mannarino & Deblinger (2006). This therapy has the following 10 components for the trauma-focused approach:

The first 5 components convey basic information and skills, components 6 to 10 deal with trauma exposure and preparing the family for the time after therapy:

- Psychoeducation

- Parenting skills

- Relaxation

- Expression and modulation of affects

- Cognitive processing and coping

- Trauma narrative

- Cognitive coping and working through

- In-vivo coping with traumatic memories

- Joint parent-child sessions

- Enhance future security and development

The therapy manual emphasizes the importance of the therapist's sensitivity in building a trusting therapeutic relationship and in using the therapy manual flexibly and creatively (Cohen, 2006).

The second, very effective method for treating traumatized children and adolescents is EMDR . It is based on a theoretical model that aims to shift memories of thoughts, feelings and physical sensations related to the traumatic event and which are aversive from implicit memory to explicit memory. This means that these memories are no longer cut off from normal information processing. They can be put back into context with already existing memories and experiences and processed and can thereby lose their strong aversion (NICE, 2005).

In an EMDR session, the patient is instructed to remember the traumatic event, while bilateral physical stimulation (eye movements, touches, sounds) is provided by the therapist at various stages of the treatment. The goals of the EMDR procedure are desensitization, reduction of arousal as well as gaining a new insight or a changed conviction regarding the traumatic event experienced. The EMDR procedure thus contains elements of graded exposure, cognitive restructuring and classical conditioning (NICE, 2005).

The study carried out by Kemp, Drummond and McDermett (2009) proves the suitability of the EMDR procedure for traumatized children and adolescents.

In addition to the therapeutic approaches mentioned so far, research shows that narrative exposure therapy (NET; Schauer, Neuner & Elbert, 2005) can also be a promising method for children and adolescents. According to the study, NET showed an effective reduction in trauma symptoms in children and adolescents. An improvement occurs even if the young patient's environment remains unstable, insecure and unpredictable (Robjant & Fazel, 2010). The name KIDNET has now been used for narrative exposure therapy for children and adolescents. On the basis of psychological and neuroscientific findings - especially on learning and memory - traumatic events are processed with the aim of psychological and autobiographical integration (Sonnenmoser, 2009). The short-term therapy usually extends over eight phases (= sessions).

Pharmacotherapy

In the treatment of PTSD in children and adolescents, pharmacotherapy is not recommended due to insufficient research (NICE, 2005). If it is considered, then only in conjunction with psychotherapy - for example, if there are also severe depressive or other symptoms, the child / adolescent does not respond well to the therapy (AACAP, 2010) or no psychotherapy is available. In the meantime, a limited effectiveness has been shown for different active substances, depending on which phase of PTSD the patient is in and which goal is to be achieved, but research is not yet far enough to be able to make general recommendations (Huemer, 2010) .

literature

Monographs

- Marylene Cloitre, Lisa Cohen, K. Koenen: Treating Survivors of Childhood Abuse . Guilford, New York 2006, ISBN 1-59385-312-2 . (Practice-oriented comprehensive overview of the effects of traumatic experiences in children and adolescents as well as the concrete phase-oriented treatment approach) .

- J. Cohen, A. Mannarino, E. Deblinger: Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy in children and adolescents . Springer, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-540-88570-2 (Describes the implementation of a complete therapy with a behavioral approach for trauma and grief in children and adolescents with clear materials and examples).

- A. Krüger: Acute psychological trauma in children and adolescents. A manual for outpatient care . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-608-89065-5 (Conveys basic knowledge about traumatization and its effects as well as the first steps in treatment for adolescents after an acute trauma).

- DJ Kolko, CC Swenson: Assessing and treating physically abused children and their families . Sage Publ., London 2002, ISBN 978-0-7619-2149-3 (Practice-oriented approach to the diagnosis and treatment of physically abused children and descriptions of child, parent and family-specific treatments).

- MA Landolt: Psychotraumatology of Childhood . Hogrefe, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 978-3-8017-2450-4 (overview of the development, diagnosis, course, prevention and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorders in children and adolescents).

- MA Landolt, T. Hensel: Trauma therapy in children and adolescents . Hogrefe, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-8017-2071-1 (Comprehensive overview of current methods of trauma therapy in children and adolescents. (TF-CBT, EMDR, narrative exposure therapy, play therapy, etc.)).

- R. Steil, R. Rosner: Post-traumatic stress disorder . Hogrefe, Göttingen 2009 (current description of the PTB in childhood and adolescence, practice-oriented and comprehensive insight into diagnostics and treatment, as well as an overview of current research results and helpful materials).

Parents' guides and children's books

- A. Krüger: First aid for traumatized children . Patmos, Düsseldorf 2007, ISBN 978-3-8436-0146-7 (This book shows clearly and with many examples what adults can do to help children cope with trauma).

- A. Krüger: Powerbook, first aid for the soul . Elbe & Krueger Verlag, Hamburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-9814282-0-9 (With the Powerbook, affected young people can better understand their traumatic experiences with the help of numerous case studies. In simple language and with clear images, the author conveys possibilities for self-healing which lead to faster, noticeable relief).

- R. Lackner, B. Lueger-Schuster, K. Pal-Handl: How Pippa learned to laugh again. A picture book for children . Springer, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-211-22415-7 (With the help of this book, affected children are given the opportunity to express themselves, to ask questions and thus to process traumatic experiences).

- B. Lueger-Schuster, K. Pal-Handl: How Pippa learned to laugh again. Parents' guide for traumatized children . Springer, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-211-22416-5 (The parenting guide gives easy-to-understand tips on coping with trauma and grief and provides helpful information about advice centers, web pages and further literature).

- R. Rosner, R. Steil: Advisor Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Information for those affected, parents, teachers and educators . Hogrefe, Göttingen 2009 (The guidebook provides understandable information on the disorders of post-traumatic stress disorder in childhood and adolescence and on its treatment).

- U. Endres: I was tender, it was bitter. Sexual abuse of boys and girls. Recognize, protect, advise . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2001, ISBN 978-3-462-03328-1 (EA Cologne 2001; provides facts, backgrounds, causes and consequences of sexual abuse and offers concrete help).

Web links

- Help for children and young people after violence and disasters. National Institute of Mental Health, USA, German version: Dieter Berger, psychotrauma-kinder.de, May 24, 2018 ( archive ).

- Rita Rosner, Regina Steil: Post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. DNP - The Neurologist & Psychiatrist, 2013; 14 (1), pp. 2-10, ( archive ).

- Marion Sonnenmoser: Post-traumatic stress disorder - extent underestimated in children. Deutsches Ärzteblatt, PP 8, Issue 9, September 2009, pp. 413-416, ( archive ).

- German version of the Children's Impact of Event Scale. http://www.childrenandwar.org ( Word document 26 kB ; accessed on October 2, 2012, archive ).

- Post-traumatic stress disorder aumatic stress disorder. NICE guideline. National Institute for Health Care and Excellence. Published: 5 December 2018, ISBN 978-1-4731-3181-1 ( PDF 226kB ).

References

- AACAP: Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder . In: Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , Vol. 49 (2010), Issue 4, pp. 414-430, ISSN 0890-8567 .

- KM Abram, JJ Washburn, LA Teplin, KM Emanuel, EG Romero, GM McClelland: Posttraumatic stress disorder and psychiatric comorbidity among detained youths . In: Psychiatric Services , Vol. 58 (2007), No. 10, pp. 1311-1316, ISSN 1075-2730 .

- A. Bokszczanin: Parental support, family conflict, and overprotectiveness. Predicting PTSD symptom levels of adolescents 28 months after a natural disaster . In: Stress & Coping. An International Journal , Vol. 21 (2008), Issue 4, pp. 325-335.

- JA Boscarino: Posttraumatic stress disorder and physical illness. Results from clinical and epidemiologic studies . In: Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences , No. 1032 (2004), pp. 141-153, ISSN 0077-8923 .

- MB Bronner, H. Knoester, AP Bos, BF Last, MA Grootenhuis: Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in children after pediatric intensive care treatment compared to children who survived a major fire disaster . In: Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health , Vol. 2 (2008), Issue 9, ISSN 1753-2000 (accessed December 14, 2010 at http://www.capmh.com/content/2/1/9 ) .

- R. Ceballo, TA Dahl, MT Aretakis, C. Ramirez: Inner-city children's exposure to community violence. How much do parents know? In: Journal of Marriage and Family , Vol. 63 (2001), pp. 927-940, ISSN 0022-2445 .

- Child Behavior Checklist: Parent Questionnaire for Young and Preschool Children (CBCL-1½-5) . German Working Group on Child, Youth and Family Diagnostics (KJFD), Cologne 2002.

- JA Cohen, O. Bukstein, H. Walter, RS Benson, A. Chrisman, TR Farchione et al. : Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder . In: Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , Vol. 49 (2010), pp. 414-430, ISSN 0890-8567 .

- JA Cohen, MS Scheeringa: Post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis in children. Challenges and promises . In: Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience , Vol. 11 (2009), pp. 91-99, ISSN 1294-8322 .

- JA Cohen, AP Mannarino, E. Deblinger: Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents . Guilford, New York 2006, ISBN 978-1-59385-308-2 .

- Judith A. Cohen: Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy in children and adolescents . Springer, Heidelberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-540-88570-2 .

- WE Copeland, G. Keeler, A. Angold, EJ Costello: Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood . In: Archives of General Psychiatry , Vol. 64 (2007), pp. 577-584, ISSN 0003-990X .

- J.-M. Darves-Bornoz, J. Alonso, G. de Girolamo, R. de Graaf, J.-M. Haro, V. Kovess-Mas Sicherheit et al. : Main traumatic events in Europe. PTSD in the European study of the epidemiology of mental disorders survey . In: Journal of Traumatic Stress , Vol. 21 (2008), Issue 5, pp. 455-462, ISSN 0894-9867 .

- MD De Bellis, SR Hooper, DP Woolley, CE Shenk: Demographic, maltreatment, and neurobiological correlates of PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents . In: Journal of Pediatric Psychology , Vol. 35 (2010), Issue 5, pp. 570-577, ISSN 0146-8693 .

- C. Dehon, MS Scheeringa: Screening for preschool posttraumatic stress disorder with the Child Behavior Checklist . In: Journal of Pediatric Psychology , Vol. 31 (2006), pp. 431-435, ISSN 0146-8693 .

- German Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy a. a. (Ed.): Guidelines for the diagnosis and therapy of mental disorders in infants, children and adolescents . 3rd edition. Deutscher Ärzte Verlag, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-7691-0492-9 .

- V. Domanskaité-Gota, A. Elklit, DM Christiansen: Victimization and PTSD in a lithuanian national youth probability sample . In: Nordic Psychology , Vol. 61 (2009), Issue 3, pp. 66-81, ISSN 1901-2276 .

- A. Dyregrov: The process in critical incident stress debriefings . In: Journal of Traumatic Stress , Vol. 10 (1979), pp. 589-605, ISSN 0894-9867 .

- A. Dyregrov, G. Kuterovac, A. Barath: Factor analysis of the Impact of Event Scale with children in war . In: Scandinavian Journal of Psychology , Vol. 36 (1996), pp. 339-350, ISSN 0036-5564 .

- A. Ehlers: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders (Advances in Psychotherapy; Vol. 8). Hogrefe, Göttingen 1999, ISBN 3-8017-0797-0 .

- C. Essau, J. Conradt and F. Petermann: Frequency of post-traumatic stress disorder in adolescents. Results of the Bremen youth study . In: Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychotherapie , Vol. 27 (1999), Issue 1, pp. 37-45, ISSN 1422-4917 .

- C. Essau, J. Conradt, F. Peterman: Frequency, comorbidity, and psychological impairment of anxiety disorders in German adolescents . In: Journal of Anxiety Disorders , Vol. 14 (2000), Issue 3, pp. 263-279, ISSN 0887-6185 .

- EB Foa, KM Johnson, NC Feeny, KR Treadwell: The child PTSD symptom scale. A preliminary examination of its psychometric properties . In: Journal of Clinical Child Psychology , Vol. 30 (2001), pp. 376-384, ISSN 0047-228X .

- B. Früh, T. Kultalahti, R. Rosner: Checklist for acute exposure . Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2007.

- B. Früh, T. Kultalahti, H.-J. Röthlein, R. Rosner: Predictability of post-traumatic stress in children and adolescents after traumatic events in school . In: Childhood and Development , Vol. 17 (2008), Issue 4, pp. 219-223, ISSN 0942-5403 .

- M. Gavranidou, R. Rosner: The weak sex? Gender and PTSD . In: Depression and Anxiety , Vol. 17 (2003), pp. 130-139, ISSN 1091-4269 .

- A. Graf, D. Irblich, MA Landolt: Post-traumatic stress disorders in infants and young children . In: Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie , Vol. 57 (2008), pp. 247-263, ISSN 0032-7034 .

- Th. Hensel: EMDR with children and adolescents after single-incident trauma . In: Journal of EMDR practice and research , Vol. 3 (2009), Issue 1, pp. 2-9, ISSN 1933-320X .

- J. Huemer, F. Erhardt, H. Steiner: Posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. A review of psychopharmacological treatment . In: Child Psychiatry and Human Development , Vol. 41 (2010), pp. 624-640, ISSN 0009-398X .

- Z Jia, W. Tian, X. He, W. Liu, Ch. Jin, H. Ding: Mental health and quality of life survey among survivors of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake . In: Quality of Life Research , Vol. 19 (2010), pp. 1381-1391, ISSN 0962-9343 .

- M. Kemp, P. Drummond, B. McDermott: A wait-list controlled pilot study of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for children with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms from motor vehicle accidents . In: Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry , Vol. 14 (2009), ISSN 1359-1045 .

- S. Kingston, C. Raghavan: The relationship of sexual abuse, early initiation of substance use, and adolescent trauma to PTSD . In: Journal of Traumatic Stress , Vol. 22 (2009), Issue 1, pp. 65-68, ISSN 0894-9867 .

- I.-T. Kolassa, S. Kolassa, V. Ertl, A. Papassotiropoulos, DJ-F. De Quervain: The risk of posttraumatic stress disorder after trauma depends on traumatic load and the catechol-O-methyltransferase Val158Met polymorphism . In: Biological Psychiatry , Vol. 67 (2010), Issue 4, pp. 304-308, ISSN 0006-3223 .

- DJ Kolko, AE Kazdin: Emotional / behavioral problems in clinic and nonclinic children. Correspondence among child, parent and teacher reports . In: Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , Vol. 34 (1993), pp. 991-1006, ISSN 1469-7610 .

- T. Kultalahti, R. Rosner: Risk factors of post-traumatic stress disorder after trauma type I in children and adolescents . In: Childhood and Development , Vol. 17 (2008), Issue 4, pp. 210-218, ISSN 0942-5403 .

- M. Landolt, M. Vollrath, K. Ribi, K. Timm, F. Sennhauser, H. Gnehm: Incidence and course of post-traumatic stress reactions after traffic accidents in childhood . In: Childhood and Development , Vol. 12 (2003), Issue 3, pp. 184-192, ISSN 0942-5403 .

- R. Meiser-Stedman, P. Smith, E. Glucksman, W. Yule, T. Dalgleish: The posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis in preschool- and elementary school-age children exposed to motor vehicle accidents . In: American Journal of Psychiatry , Vol. 165 (2008), Issue 10, pp. 1326-1337, ISSN 0002-953X .

- JT Mitchell: When disaster strikes ... The critical incident stress debriefing . In: Journal of Emergency Medical Service , Vol. 8 (1983), pp. 36-39, ISSN 0197-2510 .

- A. Perkonigg, RC Kessler, S. Storz, H.-U. Wittchen: Traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder in the community. Prevalence, risk factors and comorbidity . In: Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica , Vol. 101 (2000), pp. 46-59, ISSN 0001-690X .

- A. Perkonigg, H. Pfister, MB Stein, M. Hoefler, R. Lieb, A. Maercke, H.-U. Wittchen: Longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in a community sample of adolescents and young adults . In: European Neuropsychopharmacology , Vol. 16, Suppl. 4 (2006), pp. 453-454, ISSN 0924-977X .

- T. Petersen, A. Elklit, J. Gytz Olesen: Victimization and PTSD in a Faroese youth total-population sample . In: Scandinavian Journal of Psychology , Vol. 51 (2010), pp. 56-62, ISSN 0036-5564 .

- K. Robjant, M. Fazel: The Emerging Evidence for Narrative Exposure Therapy . Hogrefe, Göttingen 2010.

- N. Rohleder, A. Karl: Role of endocrine and inflammatory alterations in comorbid somatic diseases of post-traumatic stress disorder . In: Minerva Endocrinologica , Vol. 31 (2006), Issue 4, pp. 273-288, ISSN 0391-1977 .

- R. Rosner, M. Hagl: Post-traumatic stress disorder . In: Childhood and Development , Vol. 17 (2008), Issue 4, pp. 205-209, ISSN 0942-5403 .

- H. Saß, H.-U. Wittchen, M. Zaudig: Diagnostic and statistical manual. Mental disorders, text revision, DSM-IV-TR . Hogrefe, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3-8017-1660-0 .

- M. Schauer, F. Neuner, T. Elbert: Narrative Exposure Therapy . Hogrefe, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 0-88937-290-X .

- MS Scheeringa, CH Zeanah: Reconsideration of Harm's Way. Onsets and comorbidity patterns of disorders in preschool children and their caregivers following hurricane Katrina . In: Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology , Vol. 37 (2008), Issue 3, pp. 508-518, ISSN 1537-4416 .

- MS Scheeringa, CH Zeanah, MJ Drell, JA Larrieu: Two approaches to the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder in infancy and early childhood . In: Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , Vol. 34 (1995), pp. 191-200, ISSN 0890-8567 .

- MS Scheeringa, CH Zeanah, L. Myers, FW Putnam: New findings on alternative criteria for PTSD in preschool children . In: Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , Vol. 42 (2003), pp. 561-570, ISSN 0890-8567 .

- MS Scheeringa, CH Zeanah: Symptom expression and trauma variables in children under 48 months of age . In: Infant Mental Health Journal , Vol. 16 (1995), No. 4, pp. 259-270, ISSN 0163-9641 .

- M. Simons, B. Herpertz-Dahlmann: Traumas and post-traumatic disorders in children and adolescents: A critical overview of classification and diagnostic criteria . In: Journal for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy , Vol. 36 (2008), Issue 3, pp. 151–161, ISSN 1422-4917 .

- C. Smith Stover, H. Hahn, S. Berkowitz, JY Jamie: Agreement of parent and child reports of trauma exposure and symptoms in the early aftermath of a traumatic event . In: Psychological Trauma. Theory, Research, Practice And Policy , Vol. 2 (2010), Issue 3, ISSN 1942-9681 .

- M. Sonnemmoser: Post-traumatic stress disorder. Extent underestimated in children . In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt , Heft 9 (2009), pp. 413-416, ISSN 0012-1207 .

- P. Stallard: Psychological interventions for post-traumatic reactions in children and young people. A review of randomized controlled trials . In: Clinical Psychology Review , Vol. 26 (2006), pp. 895-911, ISSN 0272-7358 .

- R. Steil, G. Füchsel: IBS-KJ. Interviews on stress disorders in children and adolescents . Hogrefe, Göttingen 2006.

- R. Steil, R. Rosner: Advisor "Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder" . Hogrefe, Göttingen 2009, ISBN 978-38017-1819-0 .

- AM Steinberg, MJ Brymer, KB Decker, RS Pynoos: The University of California at Los Angeles post-traumatic stress disorder reaction index . In: Current Psychiatry Reports , Vol. 6 (2004), pp. 96-100, ISSN 1523-3812 .

- A. Streeck-Fischer: Problems in the diagnosis and treatment of traumatized children and adolescents . In: F. Lamprecht (Ed.): Where is trauma therapy developing? (Learning to live; Vol. 199). Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-608-89041-9 .

- EV Trask, K. Walsh, D. DiLillo: Treatment effect for common outcomes of child sexual abuse. A current meta-analysis . In: Aggression and violent behavior , Vol. 16 (2011), Issue 1, pp. 6-19, ISSN 1359-1789 .

- BA Van der Kolk: Developmental trauma disorder. A new, rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories . In: Psychiatric Annals , Vol. 35 (2005), pp. 401-408, ISSN 0048-5713 .

- BA Van der Kolk, RS Pynoos, C. Cicetti, M. Cloitre, W. D'Andrea, JD Ford et al .: Proposal to include a developmental trauma disorder diagnosis for children and adolescents in DSM-V . Inproceedings, February 1, 2009 ( archive ).

- R. Yehuda, A. Bell, LM Bierer, J. Schmeidler: Maternal, not paternal, PTSD is related to increased risk for PTSD in offspring of Holocaust survivors . In: Journal of Psychiatric Research , Vol. 42 (2008), Issue 13, pp. 1104-1111, ISSN 0022-3956 .

- W. Yule, D. Bolton, O. Udwin, S. Boyle, D. O'Ryan, J. Nurrish: The long-term psychological effects of a disaster experienced in adolescence. The incidence and course of PTSD . In: The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , Vol. 41 (2000), Issue 4, pp. 503-511, ISSN 0021-9630 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Marion Sonnenmoser: Post-traumatic stress disorder - extent underestimated in children. Deutsches Ärzteblatt, PP 8, Issue 9, September 2009, pp. 413-416, (archive) .

- ^ Rita Rosner, Regina Steil: Post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. DNP - The Neurologist & Psychiatrist, 2013; 14 (1), pp. 2-10, (archive) .

- ↑ (Giaconia, et al., 1995; Nader et al., 1993; Saigh, 1991, quoted in Steil & Rosner, 2009)

- ↑ Help for children and young people after violence and disasters. National Institute of Mental Health, USA, German version: Dieter Berger, psychotrauma-kinder.de, May 24, 2018.

- ^ Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Children Affected by Sexual Abuse or Trauma. Child Welfare Information Gateway Children's Bureau / ACYF, August 2012.

- ↑ a b Post-traumatic stress disorder aumatic stress disorder. NICE guideline. National Institute for Health Care and Excellence. Published: 5 December 2018, ISBN 978-1-4731-3181-1 (PDF 226 kB).