Rock of Cashel

The Rock of Cashel ( Irish Carraig Phádraig ), near the town of Cashel , about 20 km north of Cahir in County Tipperary in Ireland , is a unique monument of Irish history.

The mountain rises 65 m high and is considered an Irish landmark. As the seat of fairies and spirits, it was venerated in ancient times.

In the 4th century the clan of the Eoghanachta , the later MacCarthys, conquered the rock and expanded it into a clan seat. This was of strategic importance due to its elevated position, which promised a good overview of the surrounding country.

history

Since the 4th century, Caiseal (old Irish for stone castle) was the seat of the kings of Munster and was equivalent in meaning to the other seats of the provincial rulers including Tara . St. Patrick made the fortress a bishopric in the 5th century.

In the early 10th century, Cormac mac Cuileannáin, also known as bishop and teacher, ruled Munster. He fell in 908 in the Battle of Ballaghmoon, which was fought between Leinster and Munster. The rock later fell to the O'Brian clan who became kings in Munster. Brian Boru , who later fell in the battle against the Vikings , was crowned King of Munster there in 977.

King Muircheartach Ó Briain gave the rock to the Bishop of Limerick on the occasion of the first synod in Ireland in 1101 .

Cormac Mac Carthaigh became the first Archbishop of Cashel in 1127 and built Cormac's Chapel in the Irish-Romanesque style that same year . The small church is next to the round tower the oldest building on the Rock of Cashel. Two master builders from a monk delegation from Regensburg , which was in close cultural exchange with Cashel, were also involved.

In 1172, after conquering part of Ireland , Henry II of England visited the castle, where princes and clergy paid homage to him. Thereby they achieved the independence of the Irish Church . In the 13th century, the construction of the great Gothic cathedral began. The Earl of Kildare set them on fire and had to justify himself to the king. He apologized for wanting to kill the archbishop, whose presence in the cathedral he suspected.

In the 15th century, the bishop's castle was built on the west side, which was integrated into the church. The Hall of the Vicars Choral is now the entrance to the entire complex.

After the death of Archbishop Roland Baron in 1561, competing bishops were appointed by the Pope (Roman Catholic) and the (English) Crown ( Anglican ), with the latter coming to power. From 1571 to 1622 Miler Magrath , the "villain of Cashel", held the title; his tomb with a self-made inscription can be seen in the cathedral choir .

In 1641 the Rock of Cashel became Catholic again in the course of the Irish Confederation Wars, but in 1647 it returned to the Anglican Church after a siege by the English commander of Cork, Murrough O'Brien , Earl of Inchiquin. The Confederate forces and Roman Catholic clergy, including Theobald Stapleton , were executed. The English troops also looted or destroyed many important religious works of art.

The Anglican Church gave up the complex in the 18th century. In 1749 the roof of the cathedral was removed by Arthur Price, an Anglican bishop of Cashel. As a result, the facility fell into disrepair.

Legends

Saint Patrick is said to have made the place a bishopric and baptized King Aengus in 450 AD . A legend tells that during the ceremony Patrick accidentally rammed his crosier into the foot of Aengus, which Aengus considered to be a Christian baptismal ritual and which he endured indifferently. In the early Middle Ages the Englishman Albert was elected archbishop at the request of the people in Cashel.

Buildings on the rock

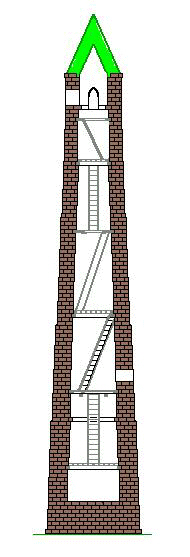

The oldest and tallest of the Cashel buildings is the very well-preserved round tower (28 meters or 90 feet high), it probably dates from 1101 (according to another source: 849). The entrance is 3.60 meters (12 feet) above the ground. It has the typical pointed roof of the round towers. The tower was built of stone without mortar. Only recently have joints been filled with mortar for safety reasons.

Cormac's Chapel , the chapel of King Cormac Mac Carthaig of Munster, was begun in 1127 and consecrated in 1134. The building consists of a central nave and a chancel, whereby the central nave and the chancel are not on the same line. There are two towers to the side of the chancel. Unlike most Irish Romanesque churches, the church is richly decorated. The abbot of Regensburg sent two of his carpenters to take care of the work. The two towers on the sides of the transition between the nave and the choir reveal their Germanic influence, this shape is otherwise not known in Ireland. Other notable features of the building, both indoors and outdoors, are the portico, barrel vault, carved tympanum over both doors, and the magnificent north gate. It contains one of the best preserved Irish frescoes from this period. Extensive restoration work on the chapel was completed in 2017.

The cathedral, built between 1235 and 1270, is a Gothic cruciform church without aisles. A tower from the 15th century rises above the crossing . At the same time, a large residential tower was built in the west. A spiral staircase can be used to climb up to the battlements, where you can enjoy a wonderful view. Next to the church entrance is the old stone on which the kings of Munster were crowned.

The Hall of the Vicars Choral was built in the fifteenth century by Archbishop O'Hedian. Laymen (sometimes minor canons ) were appointed as vicars choir , who took on the task of singing during the service in the cathedral. In Cashel there were originally eight of these singers, each with their own seal. This was later reduced to five honorary singers who had other singers as deputies, a practice that lasted until 1836.

The building consists of the hall and the later built dormitory. The vicar's main living room was on the upper floor.

The restoration of the hall was carried out by the Public Works Office as a project for the preservation of European monuments in 1975. In the rooms there is a museum about the history of the rock, and in the basement is the heavily weathered St. Patrick's Cross from the 12th century. It shows a figure of Christ and the figure of a bishop, the cross lacks the otherwise typical ring around the intersection. The small town of Cashel (Caiseal), which arose during the construction of the cathedral, also has attractions to offer, such as the ruins of the 13th century Hore Abbey at the foot of the rock. There clergy were trained who went to Regensburg. The Schottenportal in Regensburg is a reminder of this . In the immediate vicinity is the former Dominican branch Dominic's Abbey Cashel .

Location

The castle was used as the location for the medieval children's series Mystic Knights . In the series she depicts the Temra castle of the evil Maeve, the appearance of the castle has been digitally edited. Only the border walls and parts of the main building can be seen in the photos.

literature

- Michael Richter : Art. Cashel. I. story . In: Lexikon des Mittelalters , Vol. 2, Sp. 1546–1547.

- Dagmar Ó Riain-Raedel: “Like the German Emperor”. Sacred topography and Coronation Church in Cashel, Ireland . In: Caspar Ehlers (ed.): Places of Power - Places of rule - Lieux du Pouvoir (= German royal palaces. Contributions to their historical and archaeological research , Vol. 8). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 3-525-35600-5 , pp. 313-371.

photos

Web links

Coordinates: 52 ° 31 ′ 5 " N , 7 ° 54 ′ 41" W.

Footnotes

- ↑ Ingeborg Meyer-Sickendiek: God's learned Vaganten. On the trail of Irish mission and culture in Europe . Seewald, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-512-00591-8 , p. 68.

- ↑ Liam de Paor: The age of the Viking wars (9th and 10th centuries) . In: Theodore W. Moody, Francis Xavier Martin (eds.): The course of Irish history . Mercier, Cork, 17th ed. 1987, ISBN 0-85342-715-1 , pp. 91-106, here p. 104.