Savon de Marseille

The Savon de Marseille , or Marseille soap, is a type of soap that results from the saponification of a mixture of mostly vegetable oils with soda . It can be produced both industrially and by hand .

The name "Savon de Marseille" is not a registered designation of origin , but only corresponds to a codified manufacturing process that guarantees a minimum content of fatty acids . Fats other than olive oil may be used in this procedure , including tallow of animal origin.

The first soap maker was listed in the Marseille region in 1370. The formula of this soap was regulated in the 17th century under King Louis XIV . In 1688 Colbert issued an edict restricting the use of the name "Savon de Marseille" to soaps made with olive oil in the Marseille region. Historically , the traditional Marseille soap, made only from olive oil, was guaranteed to have a fatty acid content of 72%.

The Marseille region had around 90 soap factories in the 19th century. After 1950, their decline began with the rise of synthetic detergents. China and Turkey are the largest producers of Savon de Marseille today.

history

The birth of the Marseille soap industry

Soap has been used in France since ancient times. The first century Roman encyclopedist Pliny reports in his book Naturalis Historia that the Gauls use a product based on sebum and ash to dye their hair red. This soap acted as a gel and hair bleach.

The origin of the Savon de Marseille is the Aleppo soap from Syria , which has existed for thousands of years. The method of production, based on olive oil and laurel , spread throughout the Mediterranean after the Crusades through Italy and Spain to Marseille.

The Marseille soap factories from the 12th century initially only used the olive oil obtained in Provence as a raw material. The soda, a term that at the time refers to a more or less pure sodium carbonate , came from the ashes of plants in salty environments, especially salicornias . It is sufficient to collect the combustion residues of the vegetable matter with a high salt content and extract it by dissolving it. To do this, the moist ash was placed in a cloth bag and pressed out with the help of long sticks. The liquid, containing the soda and other sodium salts, was collected in a vat and left in the sun until the moisture had evaporated. The same procedure was used for the extraction of potassium salts from wood ash. In 1371, Crescas Davin is mentioned as the first Marseille soap maker to use soda. In 1593, Georges Prunemoyr went beyond the traditional scale of soap production and founded the first manufacture in Marseille.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the production of soap factories in Marseille barely met the requirements of the city and its territory. Soap from Genoa and Alicante even reached the port of Marseille.

In 1660 there were seven factories in the city with an annual output of nearly 20,000 tons. Under Louis XIV, the quality of the soap was so high that “Savon de Marseille” became a common name. It was a green soap that was mainly sold in 5 kg bars or 20 kg loaves.

On October 5, 1688, an edict of Louis XIV signed by Jean-Baptiste Colbert Seignelay , son of Colbert , secretary of the royal family, regulated the manufacture of soap. Article III of the edict states that the soap must be boiled in large cauldrons and that no animal fats and oils may be used. The oil content must be at least 72%. The soap factories had to cease operations in the summer because the heat affected the quality of the soap. Compliance with this regulation ensured the quality of the soap and made the Marseille soap factories famous.

At the same time, new soap factories sprang up in the region, in Salon-de-Provence , Toulon and Arles .

The soap industry

In 1786, 49 soap factories in Marseille produced 76,000 tons and employed 600 workers at the height of production; in addition, 1,500 prisoners were loaned from the galley arsenal.

After the economic upheaval caused by the French Revolution, Marseille soap production continued to grow to 62 soap factories in 1813. At that time, the soda was made from sea salt and sulfuric acid, which is produced by burning sulfur, limestone and charcoal, using the chemical process developed by Nicolas Leblanc .

From 1820 new fats were imported and transported through the port of Marseille. Palm oil, peanut oil, coconut oil and sesame oil from Africa or the Middle East were used to make soap.

The Marseille soap factories competed with English or Parisian soap makers who could use tallow to make a cheaper soap.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the city of Marseille had ninety soap factories. In 1906, François Merklen established the formula for Marseille soap: 63% coconut oil or palm oil, 9% soda or sea salt, 28% water. This industry flourished until the First World War, when the shipping of seeds severely affected the activity of soap manufacturers. In 1913 production was 180,000 tons and was reduced to 52,817 tons in 1918.

After the war, the soap factories benefited from the advancement of mechanization, although the quality of the product was maintained by using the old methods and production rose to 120,000 tons in 1938. When World War II broke out, Marseille still secured half of French production, but the years that followed were disastrous. Soap was increasingly being replaced by synthetic detergents and the Marseilles soap factories gradually closed.

In the Marseille region, only four soap factories are still making soap as it was made centuries ago, and they still produce the famous 600 gram cube with the soap factory's name and the mention "72% oil":

- Savonnerie Marius Fabre

- Savonnerie du Fer à Cheval

- Savonnerie du Midi

- Savonnerie le Sérail

These four soap factories have come together under the label "L'Union des Professionnels du Savon de Marseille" and fight for the protection and recognition of the "Savon de Marseille" as a real Marseille soap, for the respect of a traditional and authentic, centuries-old product .

Other real manufacturers are:

- Savonnerie de la Licorne

- La Savonnerie Rampal-Latour

The making of the Savon de Marseille

The saponification

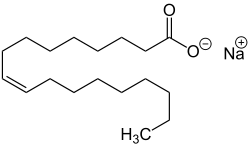

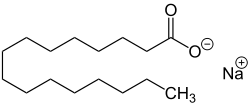

| Chemical structural formulas of the sodium salts of individual fatty acids (examples) - Components of Savon de Marseille - |

| Sodium oleate, the sodium salt of oleic acid. |

| Sodium palmitate, the sodium salt of palmitic acid. |

| Sodium stearate , the sodium salt of stearic acid. |

Marseille soap results from a chemical saponification reaction . It is a simple alkaline hydrolysis of fatty substance by a base. The fatty substances derived from fats are hydrolyzed in an alkaline environment by a base, sodium hydroxide (NaOH). The hydrolysis of the esters produces glycerine and a mixture of sodium carboxylates, ie sodium salts of fatty acids, which in a condensed phase are the determining constituents of the soap.

The Marseilles Trial

The Marseille process is a batch process for making soap. It consists of several stages:

Mashing and spinning

Soda and oils are mixed in large kettles with a volume of 10,000 to 40,000 l and heated to 120 to 130 ° C. The saponification begins. The high temperature serves to accelerate the saponification reaction. Fats and soda cannot be mixed. To facilitate the reaction, a soap base from an earlier manufacture is used, which serves to form an emulsion between the oily and aqueous phases. The mixture is continuously stirred to aid in emulsification.

Cook

To complete the saponification, the remaining emulsion is boiled for several hours with the addition of pure soda.

Relaxation and purification

The soap is washed with salt water for 3 to 4 hours to neutralize the soap and remove excess soda. In contrast to soda, soap is very slightly soluble in salt water. A precipitate forms, which is obtained by sedimentation.

Since the soap is insoluble in salt water, this process consists of adding water and sea salt, which can remove the glycerin and salty lye from the soil. The soap is separated from some water. Less than 1% glycerin, naturally produced during saponification, is retained. The glycerine is collected as a by-product of soap production.

liquefaction

The dough is brought to rest, where it hardens slightly. It is then washed with clear water to remove excess salt. The soap is then liquefied again by adding more water.

Pouring and drying

The soap is now in the form of a very fine paste, liquid and completely free of soda and salt. After decanting and mixing (homogenizing), the dough is poured into rectangular cooling containers made of cement. The dough has a temperature of 50 ° C to 60 ° C. It solidifies and forms a soap layer of the desired thickness.

The solidified soap screed is cut with a knife and laid out on shelves to dry.

Punching

The soap cubes are embossed in a molding machine. They can also be hand-marked with wooden or brass stamps.

The Savon de Marseille today

use

The Savon de Marseille is a cleaning agent that has proven itself in daily use for centuries, especially for hands and face. It is also used as a household cleaner and for washing clothes. There are flakes of Savon de Marseille for washing. It is mainly used for washing allergy and baby laundry as it does not contain any allergenic ingredients. Because the soap keeps moths away and is bactericidal, it contributed to the decline in child mortality in the 19th century.

The official definition

"Savon de Marseille" is not a registered designation of origin, but only symbolizes a production process that has been under the auspices of the General Directorate for Competition, Consumer Protection and Fraud Prevention (Direction générale de la Concurrence, de la Consommation et de la Répression des fraudes, DGCCRF) since March 2003 is registered with the Ministry of Finance. This method comes from a code that has been unilaterally validated by the French Association of Cleaning, Care and Industrial Hygiene Products (AFISE). This code defines the manufacturing method based on the four historical stages of mashing / boiling, glycerol release, washing and liquefaction to ensure a smooth crystalline phase of at least 63% oleic acids. It also defines restrictions on the use of fats, with the exception of acidic oils other than olive oil. It allows tallow, the quality of which is subject to the European Regulation (EC) No. 1774/2002 on animal derivatives used in cosmetics.

After all, this “Savon de Marseille soap code” limits additives and in particular excludes synthetic surfactants. The additives that can be used must comply with EU Directive 76/768 and then Regulation (EC) No. 1223/2009 on the placing of cosmetic, hygiene and toilet articles on the market. This code distinguishes the qualities: Savone de Marseille brut, sans colorant, sans parfum and sans additifs. So there is no obligation to make soap in Marseille in order for it to receive the designation. The name is associated with the so-called “Marseilles” saponification method, which was developed through the Leblanc process for the chemical production of caustic soda.

This code is very broad and enables a large number of soaps of various origins to benefit from the reputation of the Savon de Marseille. As a result, China and Turkey are the Savon de Marseille's largest soap makers.

Recognition as a designation of origin

In 2015, the Association des Fabricants de Savon de Marseille (AFSM) submitted an application to the European Commission for recognition as a Protected Geographical Indication via the French Patent and Trademark Office (Institut national de la propriété industrial) to use the name Savon de Marseille is protected.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k MuSaMa, Le Musée du Savon de Marseille, 1 rue Henri Foccia, Marseille. In: Tourisme Marseille // Carte Interactive & Blog de découverte de Marseille. Retrieved January 12, 2019 (fr-fr).

- ^ Pierre Larcher: Les Mille et Une Nuits. I. Nuits 1 à 327, texts traduit, présenté et annoté par Jamel Eddine Bencheikh and André Miquel; II. Nuits 327 à 719 et III. Nuits 719 à 1001, texts traduit et présenté par Jamel Eddine Bencheikh et André Miquel et annoté par André Miquel, Paris, Gallimard ["Bibliothèque de la Pléiade"], 2005 (pour le tome I) et 2006 (pour les tomes II et III ), ISBN 978-2070118533 , 65 € (tome I), 60 € (tome II et III). In: Arabica . tape 59 , no. 1-2 , January 1, 2012, ISSN 0570-5398 , p. 171–173 , doi : 10.1163 / 157005812X619014 ( brill.com [accessed January 12, 2019]).

- ↑ Histoire du Savon de Marseille. Retrieved January 12, 2019 .

- ↑ Gérard Holtzinger: Comprendre les produits d'hygiène moussants . Édilivre, Saint-Denis 2015, ISBN 978-2-332-96522-6 ( worldcat.org [accessed January 12, 2019]).

- ↑ Chambre de commerce et d'industrie de Marseille, R Collier, J Bellioud, G Rambert: Histoire du commerce de Marseille Tom. 3, Tom. 3 . Plon, Paris 1951 ( worldcat.org [accessed January 12, 2019]).

- ↑ Soap making. Retrieved January 13, 2019 .

- ↑ JM EcoSavon: The History of Soap. In: EcoSavon. June 3, 2016, accessed on January 13, 2019 (German).

- ↑ JM EcoSavon: The History of Soap. In: EcoSavon. June 3, 2016, accessed on January 13, 2019 (German).

- ↑ L'histoire du Savon de Marseille - Savonnerie Marius Fabre. Retrieved January 13, 2019 .

- ^ A b Siegbert Mattheis: Savon de Marseille, history, background, soap factories, quality. Accessed January 12, 2019 (German).

- ^ Fabrication du Savon de Marseille. In: Fer à cheval. Retrieved January 12, 2019 (fr-fr).

- ↑ * Savon de Marseille, son histoire - Perle de Provence. Retrieved January 13, 2019 .

- ↑ FABRICATION - La Savonnerie Marseillaise. Retrieved January 13, 2019 .

- ↑ Le Point magazine: Made in France: il faut sauver le savon de Marseille! July 14, 2013, accessed on January 13, 2019 (French).

- ↑ Savon de Marseille - La Maison du Savon de Marseille. Retrieved January 13, 2019 .

- ↑ Pourquoi le Savon de Marseille n'est-il pas forcément marseillais? Par Manuel Roche, CPI. Retrieved January 13, 2019 (French).

- ↑ Search database - European Commission. Retrieved January 13, 2019 .