Scala Naturae

Scala Naturae , German step ladder of nature (derived from Latin scala: ladder), is a concept of natural philosophy that shaped European thinking about nature, and especially about its living part, living beings , for many centuries . According to this idea, all objects that occur in nature can be arranged in a seamless, hierarchically organized row, from the lowest to the highest. European thinkers of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance then extended this series into the supernatural realm, where it ultimately led via the angelic hierarchy to God as the highest level. Although elements of the concept have retained their influence up to the present day, it has been largely supplanted and superseded in the science of living things, in biology , by the theories of evolution .

Antiquity

Like most of the philosophical ideas of the Occident, Plato's philosophical concepts are fundamental to the later ideas of a Scala Naturae . Over the centuries his worldview, developed in the Timaeus dialogue, remained influential . For Plato, the existence of the variable and changeable objects of the natural world depends on the eternal and unchangeable, which are not directly accessible to man and his senses, but can only be found in reason. The derived, sensually experienceable world is less good than the imperishable and immutable being, it is only real to the extent that it has a share in it. Their existence is based on the fact that what is eternal, as good, also allows the existence of further planes of being that are less perfect; these are even necessary, since the world would lack an element of perfection if not all possible beings actually came into existence. The historian Arthur O. Lovejoy calls this thought that, because of a higher perfection, everything that is possible must also exist, the “principle of abundance”. This thought implies that everything that can exist must actually exist, that all beings in nature form a complete whole, because if there was space between two forms for another, the world would be incomplete and therefore imperfect. These members, however, have different rank depending on their closeness to the eternal things.

A consequence of these thoughts ultimately leads to the tendency characteristic of Platonism that, since the essential truths lie outside the sensible world, it is not particularly worthwhile for a wise man to bother too much with the lower phenomena of the natural world, thereby making platonic ones and Neoplatonic thinkers have nothing but contempt for empirical research.

In contrast to Plato, his greatest student Aristotle was a passionate explorer of the natural world. According to his philosophy, every natural thing is a combination of form ( eidos ) and matter ( hyle ), whereby the forms exist in the world and do not form a realm of ideas outside of it. In contrast to inanimate things, living things have a soul that exists in different levels: The deepest level, the nourishing soul, belongs to all living beings. Animals also have a sensitive soul, which gives them the perception of sensory impressions and mobility. The highest level, the insightful soul, belongs among all beings (at least under the moon, sublunar) to man. There are numerous differences between different beings, some of which can be explained by purposeful causes (teleologically), whereby every living being uses its material components in an optimal, unique way in order to realize an optimal life opportunity in its environment without wasting it. Although every living being thereby has a harmonious place in the order of things, they are differently perfect. According to Aristotle, living beings inherit their shape from their ancestors through movements and properties of their blood, whereas those with “warmer” blood (although this warmth is not understood as a purely physical temperature property) are more perfect. Each type of living being has its own specific degree of perfection, with the transitions being fluid. In his work Historia animalium he says at one point (588b4-589a9 according to the Bekker census ) that has been quoted over and over again : “ Nature steps from the inanimate to the animals in such small steps that we do not recognize to which one because of the continuity Side the borders and the middle between them belong. Because after the inanimate things comes first the kind of plants and within these one differs from the other in that it seems to have more life, but the whole kind appears as more or less animate in comparison to other objects, while in comparison with the species of the animals appears inanimate ”. In De partibus animalium (681a10) he expresses it as follows: “ The sea squirts differ little from plants, but they have more animal nature than the sponges , which are not much more than plants. Because nature progresses from inanimate objects to animals in an uninterrupted sequence and in between arranges beings that live and yet are not animals, so that there is hardly any difference between neighboring groups due to their close proximity to one another. “The most imperfect, deepest beings do not inherit their form from their parents, but arise through spontaneous generation under the influence of heat directly from inanimate matter.

Theology and Christian Philosophy

Many Christian thinkers of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, first and foremost the immensely influential Doctor of the Church Augustine , but also, for example, the anonymous author who wrote under the name of Dionysius Areopagita , were not only influenced by the Bible but also by Neoplatonic ideas from Plotinus and others and created one Theology in which Christian and Neoplatonic ideas merged. Through the writings of the Church Fathers, the idea of the Scala Naturae thus became part of the binding Christian worldview. With the rediscovery of Aristotle, as a result of the Spanish Reconquista and the translations from Arabic fonts from the newly conquered Toledo By Michael Scot , Gerard of Cremona and the Toledo School of Translators , originated in the 11th century the school of scholasticism , the combined the medieval Christian tradition with the newly interpreted philosophy of Aristotle.

In addition to the thought of the honor and wisdom of the divine Creator, it was characteristic of the medieval tradition that humans did not mark the highest step of the ladder, as with Aristotle, but should at best be located somewhere in the middle. Just as there were countless “lower” creatures below man, there was above him, with the Nine Choirs of Angels , a continuously increasing series of more perfect creatures. Nor did John Locke consider it probable " that there are many more kinds of beings above than below us, since we ourselves stand farther from the infinite being of God than from the lowest kind of things, which comes closest to nothing ". For medieval natural philosophers, the idea of the Scala Naturae was particularly attractive because of this middle position. Thus the supernatural, metaphysical world was connected with the natural, physical world. Man had the rational soul in common with the angels and other higher beings, while he was connected with the nature below him through his bodily functions. In encyclopedic works such as the bestiaries , the entries were often arranged according to their rank in the scale. The obvious imperfections, such as the lack of intermediate forms, were often explained by the fact that these lived in previously unexplored regions of the world, such as the antipodes , and had simply not yet been discovered.

The great chain of beings

Building on the ideas of their predecessors, thinkers and natural philosophers of the 17th and especially the 18th century developed their concept of the “great chain of beings”. The idea was rooted in the ideas of deism and natural theology , developed especially in England . According to them, it was an outflow of God's goodness that He bestowed the grace of existence on every being that can exist, even the lowest and lowest among them. Every being has its natural place in the order of things. It cannot change this place, as it would then take the place of other beings and gaps or spaces between them are unthinkable. With that the world is as perfectly ordered as it is possible at all. John Law put it: “ If we accept the existence of a ladder of beings that gradually descends from perfection to non-being, then we soon understand the absurdity of questions like this: Why was man not made perfect? Why are his abilities and talents not the same as those of the angels? Because that amounts to the question, why he did not get into another class of beings, when all other classes have to be considered full "

Biological principle of order

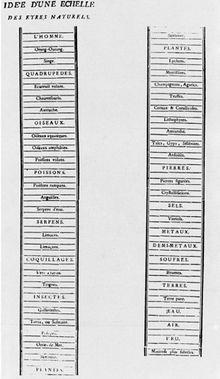

The idea of a step ladder of nature was initially retained in the developing scientific biology, since it gave the abundance of unconnected facts a common framework and a principle of order. In contrast to earlier works, which were primarily devoted to the moral position of man, now, if possible, all beings and manifestations of nature should be assigned a place in the ladder of their own right. The important natural scientist Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck established such a sequence in his work Flore Françoise (1788). In the Philosophical Account of the Works of Nature (1721) Richard Bradley undertook a similar attempt, very sophisticated in detail, to classify all beings according to their “perfection”. The illustration opposite shows a section from another scale by the Swiss naturalist Charles Bonnet. These researchers encountered great difficulties in the detailed work. A major problem was that not all beings wanted to fit into a perfectly linear sequence. Depending on the characteristic observed, different degrees of perfection were realized in the same organism. Very early on, as early as Bradley and Bonnet, considerations arose that there could be no uniform scale, but that it must be branched. In addition to the ladder (scale), this was recorded in a picture of a tree or a network. These metaphorical trees are partly similar to family trees, but had a completely different foundation; a chronological sequence or evolution still seemed almost unthinkable. Carl von Linné , the founder of modern biological taxonomy, remarked in Philosophia botanica (1751): “ Nature itself connects minerals, plants and animals; She does not connect the most perfect plants with the animals, which are considered to be the least perfect, but imperfect plants and imperfect animals are connected with each other ”.

Another debate arose about the continuity that the Scala Naturae presupposes. There have long been different views on the classification. For Aristotle and his followers, the natural variations within a species were completely different from those that existed between the different species with their respective blueprints. Other thinkers also saw seamless transitions within the categories, so that the most extreme individuals of one species continued the continuum with the most similar of another species, according to them the classification according to species was actually artificial, only the individuals real. In the age of colonialism, this idea was misused to justify “lower” human races. Eighteenth-century authors said: “ The difference between the lowest representatives of our species and the ape is not so great that, if it had been given the ability to speak, it could not claim the rank and dignity of man as the wild Hottentott or the dull native of Novaya Zemlya. "The then highly esteemed William Smellie wrote in his Philosophy of Natural History " How many transitions can be traced between a stupid Huron, or Hottentot, and a profound philosopher? The difference is immense here, but nature has combined the difference with almost imperceptible shading of the transition. In descending order of soulfulness, the next step to our shame is very small. Man, in his lowest form, is evident, both in the form of the body and in the capacity of the mind, associated with the large and small orangutans. “It was not, as later in the theory of evolution, a matter of actual relationship or temporal development, but of a proximity between“ higher ”and“ lower ”representatives of the respective category, which was represented in the theory of evolution even before corresponding tendencies.

In biology, which was developing as an independent science at that time, there were controversies between the most important anatomist of his time, Georges Cuvier , and two other important naturalists, Lamarck and Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, about the continuity of the construction plan. In the animal kingdom, Cuvier had differentiated between various classes, which he called embranchments (today, following Ernst Haeckel, called tribes ), the basic structure of which, according to him, is radically different, with no transition between them. His opponents, however, stressed that some organs could very well be classified as transitions.

Zoophytes

Already Aristotle noticed during his research on marine life (presumably on the island of Lesbos) various "lower" animals whose classification caused him difficulties because they seemed to stand between the otherwise so clearly differentiated realms of plants, animals and minerals. Sponges are alive and immobile. Do they belong to the animals or to the plants? His pupil and successor Theophrastus describes a deep-sea corallion (the precious coral Corallium rubrum ) on the one hand with the minerals, on the other hand as a plant. Other creatures such as sea squirts or sea anemones were neither clearly animal nor vegetable according to the criteria used. There was no fundamental doubt about the nature of the plants. Even the pre-Socratic natural philosophers such as Empedocles clearly assigned them to living beings, Plato accepted that they too must have a soul, which was adopted from Aristotle. The existence of stone plants or lithophytes and animal plants or zoophytes was seen as an argument for the Scala Naturae until the 18th century, which predicts an unbroken series (gradation).

Many systematic scientists of the 18th century, in addition to those already mentioned such as Bonnet, for example, John Ellis and Oliver Goldsmith and Jean-Baptiste-René Robinet , set up systems in which the zoophytes and their intermediate position, completely comparable to the ancient ideas, were accepted. The name zoophytes, in the sense of Edward Wotton's conception , was still used until the 19th century for various groups of cnidarians , some of which also have the color of plants (as discovered later, by symbiotic zooxanthellae ). Their membership in the animal kingdom was not generally accepted until the end of the 19th century.

Changes and evolution

In its traditional form, completed in the 17th century, the principle of the Scala Naturae describes an eternal and unchangeable universe. God had arranged all things well and for the best. Even the Aristotelian philosophy, which assumed an eternal universe, left little room for things that change. The famous English theologian and naturalist John Ray wrote about fossils in 1703: “ It would follow that many shellfish would have disappeared from the world, an idea that philosophers have not yet been able to accept, since they saw the demise of a species as a mutilation of the universe and to regard it as a diminution of its perfection ”(in the surviving work of Aristotle fossils are not mentioned at all, although they were known to the Greeks of his time). Eighteenth-century thinkers were increasingly dissatisfied with this situation, since such a world left no hope of improvement. The ladder (scala) interpreted more and more literally as a tendency to perfection inherent in nature, which has not yet been achieved, but towards which the world is striving. In his work Protogaea , Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz allowed the thought that the chain of beings whose existence seemed certain to him describes a process, not a state. Countless earlier beings could well have become extinct and replaced by those that did not exist then.

If there is an infinite chain of being, provide missing links are a particular problem. In the 18th century, more and more natural philosophers began about seemingly missing links, in the English Missing Links to think. In A Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Natural History (1834), William Swainson assumed a circular arrangement of species, with no beginning or end, but was only able to realize this by postulating numerous missing links that had yet to be discovered . Robert Chambers spoke in Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844) of gaps in the fossil record that could be bridged by missing links.

Building on these considerations of his time, Charles Darwin set with his fundamental work On the Origin of Species (1859) a radically different approach with his theory of evolution , which ultimately prevailed across the board despite bitter controversy among his controversies. Part of Darwin's theory is the theory of descent , with which he was able to explain the similarity between different organisms as a “family similarity” based on common ancestry. Instead of a justification from above, with decreasing degrees of perfection, there was a development from below, with (at least on average) increasing degrees of complexity. While this made it possible to explain the natural observations and facts much better, the harmony and order of the previous worldview, which had given many people confidence, was finally lost.

Afterlife: higher and lower forms of life

Most of the ideas and principles of order that were developed within the framework of the Scala Naturae concept are now considered completely out of date in biology and are no longer represented by anyone. We are convinced today that species of living beings can arise and become extinct again without adversely affecting the order of the world or God's plan in creation. The idea of spontaneous generation, according to which living beings could emerge again at any time from decaying substance or damp mud, has been refuted by careful empirical studies. The division of the world into a realm of animals, plants and minerals, which was still based on Linné's Systema Naturae , the founding work of the biological system, is only of historical interest today. “Transitional forms” and missing links are interpreted radically differently today.

Many evolutionary biologists argue, however, that thoughts that go back to the concept would have stayed in the popular view of evolutionary theory and are even still used in specialist publications. According to this view, evolution is often viewed like the progressive, evolving version of the Scala Naturae that was developed in the 18th century. According to this view, which they described as erroneous and false, evolution would be something like a narrative of progress in nature: The lower forms of life that arose first would have produced higher and higher forms, which gradually replaced them. This higher development ultimately culminated in the emergence of man, who, as the most highly developed living being, is still something like the crown of creation . In evolutionary biology, however, every living being that exists at the same time has evolved through an exactly comparable series of ancestors. The very fact that it can survive shows that it is fully up to the demands of its environment. Development tendencies or even laws, such as a hypothetical trend towards higher development, led to misinterpretations: just as complex living beings could develop even with more simply organized ancestors, the opposite occurs, i.e. simply organized living beings that had more complex ancestors. No predictions for the future can be derived from the evolutionary success at the present time. Although theories of evolution like orthogenesis , which postulated something like a goal of evolution, have hardly any adherents, it is still widely used in biology to speak of higher or lower (or basic, primitive, plesiomorphic) forms of life, for example " Lower Plants " or " Higher Mammals ". On the other hand, all terminal taxa in a clade have the same rank among each other, there is actually no justification for evaluating some of them as “more progressive” than others. Assumptions about evolutionary trends can also hinder the view of actual developments. Instead of primitive or advanced organisms, consideration should instead be directed to their characteristics , with each real organism being in fact a mosaic of “advanced” and “basic” characteristics.

Literature and Sources

- Arthur O. Lovejoy : The great chain of beings. Story of a thought. Suhrkamp Verlag, 3rd edition 2015. ISBN 978-3-518-28704-0 . Original edition: The Great Chain of Beeing. A Study of the History of an Idea. William James Lectures at Harvard University, 1933.

- Armand Marie Leroi: The lagoon or how Aristotle invented the natural sciences. Scientific Book Society Darmstadt 2017. ISBN 978-3-8062-3693-4 . Original edition: The Lagoon. How Aristotle invented Science. Bloomsbury Publishing, London 2014.

- Juliet Clutton-Brock (1995): Aristotle, The Scale of Nature, and Modern Attitudes to Animals. Social Research 62 (3): 421-440.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Arthur O. Lovejoy: The great chain of beings. Story of a thought. Suhrkamp Verlag, 3rd edition 2015. ISBN 978-3-518-28704-0 , on page 229.

- ^ Richard Jones: The Medieval Natural World. Routledge, Oxford 2013. ISBN 978-1-317-86150-8 . on page 23.

- ^ John GT Anderson: Deep Things Out of Darkness: A History of Natural History. University of California Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-520-27376-4 .

- ↑ Arthur O. Lovejoy: The great chain of beings. Story of a thought. Suhrkamp Verlag, 3rd edition 2015. ISBN 978-3-518-28704-0 , on page 260.

- ^ Mark A Ragan (2009): Trees and networks before and after Darwin. Biology Direct 2009, 4:43 doi: 10.1186 / 1745-6150-4-43 (open access).

- ↑ Olivier Rieppel (2010): The series, the network, and the tree: changing metaphors of order in nature. Biology and Philosophy 25 (4): 475-496. doi: 10.1007 / s10539-010-9216-4

- ↑ Arthur O. Lovejoy: The great chain of beings. Story of a thought. Suhrkamp Verlag, 3rd edition 2015. ISBN 978-3-518-28704-0 , on page 283.

- ^ William F. Bynum (1975): The Great Chain of Beeing after forty years, an appraisal. History of Science 13: 1-28. on page 5.

- ^ William F. Bynum (1975): The Great Chain of Beeing after forty years, an appraisal. History of Science 13: 1-28. on page 20.

- ↑ Armand Marie Leroi: The lagoon or how Aristotle invented the natural sciences. Scientific Book Society Darmstadt 2017. ISBN 978-3-8062-3693-4 . Chapter XCI.

- ↑ Armand Marie Leroi: The lagoon or how Aristotle invented the natural sciences. Scientific Book Society Darmstadt 2017. ISBN 978-3-8062-3693-4 . Chapter LXXXVII.

- ↑ Hans Werner Ingensiep : History of the plant soul . Philosophical and biological designs from antiquity to the present. Kröner Verlag, Stuttgart 2001. ISBN 978-3-520-83601-4 .

- ↑ August Thienemann (1903): The succession of things, the attempt of a natural system of natural bodies from the eighteenth century. Zoological Annals 3: 185-274 + 3 plates.

- ^ Susannah Gibson: Animal, Vegetable, Mineral ?: How eighteenth-century science disrupted the natural order. Oxford University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-101523-6

- ↑ Arthur O. Lovejoy: The great chain of beings. Story of a thought. Suhrkamp Verlag, 3rd edition 2015. ISBN 978-3-518-28704-0 , on pages 293-294.

- ↑ Armand Marie Leroi: The lagoon or how Aristotle invented the natural sciences. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft Darmstadt 2017. ISBN 978-3-8062-3693-4 , pages 316-317.

- ↑ Peter C. Kjærgaard (2011): 'Hurray for the missing link!': A history of apes, ancestors and a crucial piece of evidence. Notes & Records, the Royal Society Journal of the History of Science 65, 83-98. doi: 10.1098 / rsnr.2010.0101

- ^ Emanuele Rigato & Alessandro Minelli (2013): The great chain of being is still here. Evolution: Education and Outreach 2013 6:18. doi: 10.1186 / 1936-6434-6-18

- ↑ Kevin E. Omland, Lyn G. Cook, Michael D. Crisp (2008): Tree thinking for all biology: the problem with reading phylogenies as ladders of progress. BioEssays 30: 854-867. doi: 10.1002 / bies.20794

- ^ Frank T. Krell & Peter S. Cranston (2004): Which side of the tree is more basal? Systematic Entomology 29: 279-281.

- ↑ Mark E. Olson (2012): Linear Trends in Botanical Systematics and the Major Trends of Xylem Evolution. Botanical Review 78 (2): 154-183. doi: 10.1007 / s12229-012-9097-0

- ↑ Andrew Moore (2013): What to do about '' higher '' and '' lower '' organisms? Some suggestions. Bioessays 35: 759. doi: 10.1002 / bies.201370093