Battle for Nanking (1937)

| date | December 1. bis 13. December 1937 |

|---|---|

| place | Shanghai , Republic of China |

| output | Japanese victory |

| consequences | Nanking massacre |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 100,000 men | 200,000 men |

| losses | |

|

About 70,000 dead and wounded |

About 7,000 dead and wounded |

1937–1939

Marco Polo Bridge - Beijing-Tianjin - Chahar - Shanghai ( Sihang warehouse ) - Beijing-Hankou Railway - Tianjin-Pukou Railway - Taiyuan ( Pingxingguan , Xinkou ) - Nanjing - Xuzhou ( Tai'erzhuang ) - Henan - Lanfeng - Amoy - Wuhan ( Wanjialing ) - Canton - Hainan - Nanchang - ( Xiushui ) - Chongqing - Suixian-Zaoyang - ( Shantou ) - Changsha (1939) - South Guangxi - ( Kunlun Pass ) - Winter Offensive - ( Wuyuan )

1940–1942

Zaoyang-Yichang - Hundred Regiments - Central Hubei - South Henan - West Hebei - Shanggao - Shanxi - Changsha (1941) - Changsha (1942) - Yunnan-Burma Road - Zhejiang-Jiangxi - Sichuan

1943–1945

West Hubei - North Burma and West Yunnan - Changde - Ichi-gō - Henan - Changsha (1944) - Guilin – Liuzhou - West Henan and North Hubei - West Hunan - Guangxi (1945) - Manchukuo (1945)

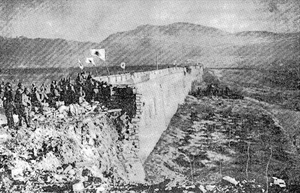

The Battle of Nanking was a battle of the Second Sino-Japanese War . In December 1937, Japanese forces captured what was then the capital of the Republic of China, Nanking , after the Chinese defenders had chaotically withdrawn from the city. After the battle, the Japanese forces committed numerous war crimes against Chinese civilians in the Nanking massacre .

background

After the outbreak of war in July 1937, the Japanese forces were able to take control of large parts of the country north of the Huang He . Contrary to Japanese expectations, the leadership of the Kuomintang under Chiang Kai-shek did not give in to Japanese pressure and planned a long war of defense against Japan. As part of this strategy, the Chinese had opened a new front at the Battle of Shanghai , but this led to the city being taken by the Japanese. The Japanese had gained a lot of territory but did not achieve their war goal of forcing the Kuomintang to bring about peace in favor of the Japanese by destroying their army.

Planning

After the battle of Shanghai, the Japanese side was about 240 km east and downstream of the Yangtze River from the capital Nanking. The Imperial Headquarters , called up on November 7th, planned an action on Nanking by the Shanghai Expeditionary Army and the 10th Army . The first-mentioned large unit ( 9th , 16th and 13th divisions ) was to advance north of Lake Tai , the 10th Army ( 6th , 18th and 114th division ) was to advance south of the lake against Nanking. The Japanese side provided four divisions for each major unit and started the march on Nanking in November 1937. In order to ensure coordination between the major units, these were combined under the command of Matsui Iwane to form the Central China Regional Army .

Chiang Kai-shek was certain that Nanking could not be successfully defended. Due to the importance of the capital, however, he did not want to give it up to the Japanese without a fight. On September 8, 1937, he entrusted General Tang Shengzhi with the supreme command of the troops in Nanking. The aim of the Chinese was to inflict the greatest possible losses on the Japanese in retreat battles with as few troops as possible. The Chinese side also planned a counterattack on the Qiantang River to slow the advance of the Japanese. The Kuomintang made 12 divisions available to defend Nanjing and the apron of the city, but they had not yet made up for the losses suffered in the previous battle for Shanghai.

course

The Japanese army used tactical air support, artillery and armored forces as it advanced. Chinese fortified positions were bypassed by the preceding elements and only encircled and smashed by units advancing. On November 19, Japanese troops captured Suzhou on the north bank of Lake Tai. Chiang tried to strengthen the front at Nanjing with 5 divisions and 2 Brigades from Sichuan . These warlord troops, which were not directly part of the KMT, fled in the face of the Japanese advance. On November 30, both the heads of the two major Japanese associations had reached the city of Nanking from the south-east and south-west and began to encircle the capital. Chiang left the city on December 7th. On December 11th, the organized resistance within the city collapsed more and more. The following day, following a withdrawal order from Chiang, the troops fled the city. On December 13, 1937, the city was completely under the control of Japanese forces. The Chinese troops lost around 70,000 people in defense of the city and the apron. Before they left, the Chinese set numerous buildings in the city on fire so as not to leave them to the Japanese.

consequences

The Japanese leadership at the army level had issued the orders to react with the greatest possible severity to Chinese resistance. Prisoners of war were not taken, but shot on the spot. The order to locate Chinese soldiers in plain clothes was equivalent to a permit to murder Chinese civilians. The 10th Army under Yanagawa Heisuke did not take any food with them to relieve their own logistics. The ordered looting of the civilian population's supplies resulted in numerous deaths. Murder, robbery, pillage and rape against the Chinese went unpunished. The behavior of the Japanese army culminated after the victory in the Nanking massacre , the most notorious war crime of the entire war.

The Japanese side was able to conquer Nanking quickly, but their goal of getting the Chinese side to surrender was not achieved. The Kuomintang government had already evacuated its military headquarters to Wuhan in October . The civil government was evacuated to the new capital, Chongqing, that same month .

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Edward J. Drea, Hans van de Ven: An Overview of Major Military Campaigns during the Sino-Japanese War 1937 - 1945. in Mark Peattie, Edward Drea, Hans van de Ven (eds.): The Battle for China - Essays on the Military History of the Sino-Japanese War of 1937-1945. Stanford, 2011, p. 31f

- ↑ Mark Peattie, Edward Drea, Hans van de Ven (eds.): The Battle for China - Essays on the Military History of the Sino-Japanese War of 1937 - 1945. Stanford, 2011, np, Map 6

- ↑ a b c Hattori Satoshi, Edward J. Drea: Japanese Operations from July to December 1937. in Mark Peattie, Edward Drea, Hans van de Ven (eds.): The Battle for China - Essays on the Military History of the Sino- Japanese War of 1937-1945. Stanford, 2011, pp. 176-180

- ↑ a b Yang Tainshi: Chiang Kai-shek and the Battles of Shanghai and Najing. in Mark Peattie, Edward Drea, Hans van de Ven (eds.): The Battle for China - Essays on the Military History of the Sino-Japanese War of 1937-1945. Stanford, 2011, pp. 155–158

- ^ Rana Mitter: China's War with Japan 1937-1945 - The Struggle for Survival. London, 2014, p. 128

- ^ Rana Mitter: China's War with Japan 1937-1945 - The Struggle for Survival. London, 2014, p. 120