Battle of Wakefield

| date | December 30, 1460 |

|---|---|

| place | Wakefield , Yorkshire , England |

| output | Victory of the House of Lancaster |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Henry Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset , Henry Percy, 3rd Earl of Northumberland |

|

| Troop strength | |

| 8,000-10,000 | 18,000 |

| losses | |

|

approx. 3,000 |

200 |

St Albans - Blore Heath - Ludlow - Northampton - Wakefield - Mortimer's Cross - St Albans - Ferrybridge - Towton - Hedgeley Moor - Hexham - Edgecote Moor - Losecote Field - Barnet - Tewkesbury - Bosworth Field - Stoke

The Battle of Wakefield took place on December 30, 1460 in Wakefield , West Yorkshire , England and was one of the main battles of the Wars of the Roses . Adversaries were troops of the House of Lancaster, who for King Henry VI. and his Queen Margaret of Anjou came in, and Richard Plantagenet's followers , 3rd Duke of York . The trigger for the battle was the Act of Accord , a parliamentary resolution that Richard of York succeeded Henry VI. made and disinherited the actual heir to the throne, Henry's son Edward of Westminster . This decision met with opposition from the nobles of the House of Lancaster and Margaret of Anjou, who then gathered troops against Richard of York. The battle ended with the victory of the House of Lancaster and the death of Richard of York.

prehistory

With the victory of the Battle of Northampton , the party of the House of York had gained the upper hand: the army of the House of Lancaster was defeated, London in the hands of the Yorkists, King Henry VI. a prisoner in the bishop's palace. Margaret of Anjou, the Queen, had fled to Wales with the Crown Prince, Edward of Westminster, under the protection of Jasper Tudor . Margaret raised troops in Wales, she also sought military support from the royal family in Scotland.

Richard of York had returned from exile in Ireland in September 1460, two months after the Battle of Northampton, and was claiming the English crown. As a compromise, Parliament decided on October 24th, with the Act of Accord , that Richard would succeed him to the throne after Heinrich's death. In October, Parliament returned land and possessions confiscated from York and his supporters, and on November 8, Richard was proclaimed heir to the throne and protector of England.

The reorganization of the succession to the throne and with it the disinheritance of Heinrich's son Edward met resistance from Queen Margaret, who wanted to protect the inheritance of her only son, who was then about six years old. There were also supporters of the House of Lancaster in Wales and the north of England, including Henry Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset , John Clifford, Lord Clifford, Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, and other nobles from the House of Lancaster. In York the troops of Margaret and the troops of the House of Lancaster met. In York, Margaret also announced her protest against the Act of Accord and prepared to march against London.

Richard of York then moved north with Salisbury with an army of 5,000 to 6,000 men, although information about his actual troop strength varies. It is also believed that Richard recruited, or intended to recruit, more soldiers along the way. Richard's army moved towards Sandal Castle in Yorkshire, one of the headquarters of the House of York, about two miles west of Wakefield. There he wanted to wait the Christmas season in a good defensive position until reinforcements arrived from his son, Eduard, Earl of March, who was still in Shrewsbury.

battle

Margarete of Anjou was not on the battlefield herself, but was in Scotland. It led Henry Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset and Henry Percy, 3rd Earl of Northumberland , the army of Lancaster in the battle. The Lancasterian army encamped around Sandal Castle: to the north the Duke of Somerset encamped with Thomas Courtenay, Earl of Devon, with Sir Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland with his troops nearby. To the west was Sir Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter, along with a contingent of Somerset troops under the command of Andrew Trollope. To the south was Sir James Butler, Earl of Wiltshire. John, Lord Clifford positioned his troops south of the village of Sandal Magna, and to the northeast the troops of Lord Roos camped. Despite their superior strength, they did not dare to attack the fortress, as they did not have sufficient military resources for a siege and an attack. Instead, the army commanders hoped they could engage Richard in battle if he dared to venture out of his fortress.

In fact, Richard left the security of his fortress on December 30th. The reports about his reasons are contradictory and can no longer be clearly clarified because there are not enough surviving sources for this battle. One theory is that because of running out of supplies Richard was forced to send out a troop that was attacked and that Richard came to the rescue with more troops, which marked the beginning of the battle. Another theory is that Richard was misled by soldiers in disguise from the Lancaster camp and launched an attack believing that reinforcements had arrived for him. Other theories suggest that he was concerned that more reinforcements would arrive for Lancaster, or it is believed that Richard of York overestimated his own strength.

Richard of York moved with his troops and his younger son, Edmund, Earl of Rutland , 17 years old , towards the open fields south of the River Calder, to an area called Wakefield Green, without realizing that Lancasterian troops were hiding in the wooded area . Richard's troops were gradually encircled and eventually overwhelmed by the flanks of Lancaster troops. About half of York's troops were killed in that battle. The Earl of Salisbury , who had remained in the fortress with some of the York troops, eventually came to the aid of Richard of York, but was ultimately unable to avert the loss of the battle.

The Duke of York was killed in the battle. His son was sent off the battlefield with his tutor, Sir Robert Aspall, but was unable to escape and was also killed. Salisbury was captured and publicly executed at Pontefract Castle the next day. Some of the most skilled Yorkist military leaders were also killed in the battle.

Consequences

After the battle, the heads of the Duke of York, his son Edmund, Earl of Rutland, and the Earl of Salisbury were impaled on stakes and displayed in York. The duke wore a paper crown and a sign that read, "Let York Overlook the City of York."

The battle did not bring about a decision in the Wars of the Roses, as London and the King remained under the control of the Earl of Warwick. With the outcome of the battle, York's eldest son Edward became the Yorkist heir to the throne. The still young Edward was to prove himself to be an excellent battle leader and politician and would later rule as King Edward IV of England .

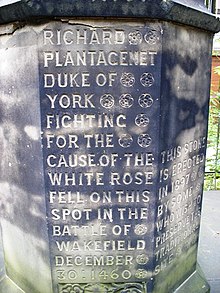

monument

Edward later erected a monument to the memory of his father on the battlefield of Wakefield, which lasted until the Civil War in the late 17th century. In 1897, locals erected a new stone monument that stands on the site of the local school and can still be viewed today.

literature

- Martin J. Dougherty: The Wars of the Roses . Amber Books, London 2015, ISBN 978-1-78274-239-5 .

- Anthony Goodman: The Wars of the Roses: Military Activity and English Society, 1452-97 . Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1981, ISBN 0-415-05264-5 .

- Philip A. Haigh: The Battle of Wakefield 1460 (illustrated ed.). Sutton Publishing, Stroud 1996, ISBN 978-0-7509-1342-3 .

- Philip A. Haigh: The Military Campaigns of the Wars of the Roses . Sutton Publishing, Stroud 1995, ISBN 0-7509-1430-0 .

- Desmond Seward: The Wars of the Roses and the Lives of Five Men and Women in the Fifteenth Century . Constable, London 1995, ISBN 0-09-474100-X .

- Alison Weir: Lancaster and York. The Wars of the Roses . Jonathan Cape, London 1995, ISBN 0-224-03834-6 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Philip A. Haigh: The Military Campaigns of the Wars of the Roses . Sutton Publishing, Phoenix Mill 1995, ISBN 0-7509-1430-0 , p. 33.

- ^ Philip A. Haigh: The Military Campaigns of the Wars of the Roses . Sutton Publishing, Phoenix Mill 1995, ISBN 0-7509-1430-0 , p. 33.

- ^ Philip A. Haigh: The Military Campaigns of the Wars of the Roses . Sutton Publishing, Phoenix Mill 1995, ISBN 0-7509-1430-0 , p. 37.

- ^ Alison Weir: Lancaster and York. The Wars of the Roses . Jonathan Cape, London 1995, ISBN 0-224-03834-6 , pp. 245-47.

- ^ A b Alison Weir: Lancaster and York. The Wars of the Roses . Jonathan Cape, London 1995, ISBN 0-224-03834-6 , pp. 252-253.

- ^ John A. Wagner: Encyclopedia of the Wars of the Roses . ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, California 2001, ISBN 1-85109-358-3 , p. 288.

- ^ Alison Weir: Lancaster and York. The Wars of the Roses . Jonathan Cape, London 1995, ISBN 0-224-03834-6 , p. 254.

- ^ Martin J. Dougherty: The Wars of the Roses . Amber Books, London 2015, ISBN 978-1-78274-239-5 , p. 105.

- ^ Philip A. Haigh: The Military Campaigns of the Wars of the Roses . Sutton Publishing, Phoenix Mill 1995, ISBN 0-7509-1430-0 , pp. 33-34.

- ^ Alison Weir: Lancaster and York. The Wars of the Roses . Jonathan Cape, London 1995, ISBN 0-224-03834-6 , p. 255.

- ^ Martin J. Dougherty: The Wars of the Roses . Amber Books, London 2015, ISBN 978-1-78274-239-5 , p. 105.

- ^ A b Philip A. Haigh: The Military Campaigns of the Wars of the Roses . Sutton Publishing, Phoenix Mill 1995, ISBN 0-7509-1430-0 , pp. 36-37.

- ^ Alison Weir: Lancaster and York. The Wars of the Roses . Jonathan Cape, London 1995, ISBN 0-224-03834-6 , p. 257.

- ^ Martin J. Dougherty: The Wars of the Roses . Amber Books, London 2015, ISBN 978-1-78274-239-5 , p. 106.

- ^ Philip A. Haigh: The Military Campaigns of the Wars of the Roses . Sutton Publishing, Phoenix Mill 1995, ISBN 0-7509-1430-0 , p. 39.

Coordinates: 53 ° 40 ′ 50 " N , 1 ° 29 ′ 32" W.