Sir Thomas More (play)

Sir Thomas More is an Elizabethan play about Sir Thomas More and the question of obeying the law and obedience to the authorities and the king. It was originally written by Anthony Munday (and Henry Chettle ) between 1596 and 1601, but received no performance permission from the censor Edmund Tillney ( Master of the Revels ) and was revised by several authors, including probably William Shakespeare as well as Thomas Heywood and Thomas Dekker . All writers except Shakespeare were associated with The Admiral's Men theater company . Often, the arrangement is placed around or in the years after 1601, when the Admiral's Men gave up their traditional theater The Rose (1600) and built a new one.

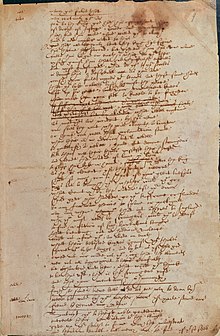

It is preserved as a handwritten manuscript in the British Library (MS Harley 7368) and it is widely believed that a few pages are in the handwriting of William Shakespeare, making it the only Shakespeare play that is preserved in his handwriting. The manuscript is entitled The Booke of Sir Thomas More and in the first version consisted of 16 sheets by a single scribe (Munday), one of which was empty. It has been heavily revised, in part in the handwriting of the censor Edmund Tillney. Two or three sheets of paper have been torn out, some areas have been deleted and seven sheets and two smaller sections have been added. In addition to the original scribe, there is also the handwriting of five people.

The play has an elaborate cast of 59 speaking roles for the theater troupes at the time, some of which could be performed by the same actors, and crowd scenes.

content

The second act has the role of Thomas More as the undersheriff of London and mediator in the May riots of 1517 in London, in which a xenophobic mob of Londoners attacked immigrants primarily from Lombardy with the aim of driving them out (shown in first act). In Thomas More's speech, probably originating from Shakespeare, with which he tries to calm down the insurgents and abandon their plan, More demonstrates to the agitators that they could also become victims of such attacks themselves if they would allow this and asks them, how they would fare if persecution forced them to seek refuge in other European countries. The subject was still very topical in Shakespeare's time, in his time there were many attacks in London, whereby the immigrants were often Huguenots at the time.

In the third act it is described how the majority of the rebels were pardoned after More stood up for them. In the fourth act, More is portrayed as the King's Lord Chancellor. His friend Erasmus von Rotterdam visits him and he entertains the Mayor of London, with a play (The Marriage of Wit and Wisdom) being performed. Thomas More is later shown in the Privy Council. He is supposed to obey a written instruction from the king, which is not specified in more detail, but refuses to sign for reasons of conscience. John Fisher, the Bishop of Rochester, also refuses and is imprisoned, More placed under house arrest. More explains the reasons to his family and when he resists further pressure, More is also imprisoned in the Tower and executed in the fifth act.

The speech by Thomas More

Grant them removed, and grant that this your noise

Hath chid down all the majesty of England;

Imagine that you see the wretched strangers,

Their babies at their backs and their poor luggage,

Plodding to the ports and coasts for transportation,

And that you sit as kings in your desires,

Authority quite silent by your brawl,

And you in ruff of your opinions clothed;

What had you got? I'll tell you: you had taught

How insolence and strong hand should prevail,

How order should be source; and by this pattern

Not one of you should live an aged man,

For other ruffians, as their fancies wrought,

With self same hand, self reasons, and self right,

Would shark on you, and men like ravenous fishes

Would feed on one another ....

Say now the king ...

Should so much come too short of your great trespass

As but to banish you, whither would you go?

What country, by the nature of your error,

should give you harbor? go you to France or Flanders,

To any German province, to Spain or Portugal,

Nay, any where that not adheres to England,

Why, you must needs be strangers: would you be pleased more

To find a nation of such barbarous temper,

That , breaking out in hideous violence,

Would not afford you an abode on earth,

Whet their detested knives against your throats,

Spurn you like dogs, and like as if that God

Owed not nor made not you, nor that the elements

Were not all appropriate to your comforts,

But chartered unto them, what would you think

To be thus used? this is the strangers case;

And this your mountainish inhumanity.

German translation:

Suppose you were rid of them and that your noise

would have dragged down all the majesty of England , imagine

the troubled strangers,

their babies on their backs and their poor luggage,

dragging themselves to the ports and coasts for the crossing,

and that you stand up like kings enthroned your desires,

the authorities silenced by your revolt

and forced you into the ruff of your opinions,

what would you have achieved? I'll tell you, you would have shown

audacity and violence prevail,

such order will be defeated, and how this pattern

to a great age not one of you,

for other ruffians are as they please

with the same hand, the same reasons and the same right

over attack you and others like sharks and

like hungry fish one eats the other ...

Now suppose the king

only holds you accountable for your great misstep to the point

that he banishes you from the country, where would you go?

Which country would you find

refuge according to the manner of your errors ? Whether you go to France or Flanders,

any of the German provinces, Spain or Portugal,

yes, any country that does not belong to England,

since you are necessarily strangers there, you would be delighted

to find a people of such barbaric disposition

who break out into hideous ones violence

you allow no place to live on earth.

Who sharpen their knives on your gargles,

despise you as dogs and as if you were not

guarded or created by God,

not that the circumstances are all to your advantage, but

dependent on them , what would you think to

be treated like that? That is the lot of the stranger,

and that is your peak inhumanity.

Authorship

It is unknown whether the work was ever performed in Elizabethan times or that of James I. It was first published in 1844 by Alexander Dyce for the Shakespeare Society. The co-authorship of Shakespeare first proposed the literary scholar Richard Simpson (1820–1876) in 1871 and he was confirmed therein in 1872 by James Spedding, the biographer and editor of the works of Francis Bacon . The writing expert and former director of the British Museum Edward Maunde Thompson identified the handwriting of D with Shakespeare's in 1916. After the publication of Thompson's book, a lively debate ensued in England that lasted until about 1928, and as a result of which the attribution was largely deemed to be authentic. Edited volumes with studies on the play that support the attribution were published in 1923 (Ed. Alfred Pollard, Maunde Thompson was also involved) and 1989 (Ed. TH Howard-Hill) and Shakespeare's authorship is largely affirmed today and the parts of the play ascribed to Shakespeare for example included in The Riverside Shakespeare (Boston 1974). But there are also skeptics about the attribution to Shakespeare.

Performances

Apart from student performances and in 1948 for the BBC on the radio, the play was first performed in the theater in 1954 and, for example, in 1964 at the Nottingham Playhouse with Ian McKellen as Thomas More. In 2005 the play was performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company .

Text output

- English

- CF Tucker Brooke (Ed.): Shakespeare Apocrypha, Oxford 1908, Reprint 1967 (the first edition made widely available)

- John S. Farmer (Ed.): The Book of Sir Thomas More, The Tudor Facsimile Texts No. 65, London and Edinburgh 1910, Reprint New York 1970 (facsimile)

- Walter Wilson Greg (Ed.): The Book of Sir Thomas More, The Malone Society 1911, Archives

- Gabrieli Vittorio, Giorgio Melchiori (eds.): Sir Thomas More, Manchester University Press 1999.

- German

- The Strangers - For More Compassion. With a foreword by Heribert Prantl . Edited and translated by Frank Günther , Munich 2016 ( dtv ), ISBN 978-3-423-14555-8

literature

- Alfred W. Pollard (Ed.): Shakespeare's Hand in the Play of Sir Thomas More, Cambridge University Press 1923.

- Scott McMillin (Ed.): The Elizabethan Theater and the "Book of Sir Thomas More", Cornell University Press 1987.

- TH Howard-Hill (Eds.): Shakespeare and Sir Thomas More; Essays on the Play and its Shakespearean Interest, Cambridge University Press 1989

- RC Bald: The Booke of Sir Thomas More and its problems, Shakespeare Survey, Volume 2, 1949, pp. 44-65

- Brian Vickers: Shakespeare Co-Author: a historical study of five collaborative plays, Oxford 2002

Web links

- “Mountainish inhumanity”: Thomas More, Shakespeare, and the refugee crisis, blog by Cynthia Haven, Stanford University (with the speech Mores from the play presented by Ian McKellen)

- The Book of Sir Thomas More: Shakespeare's only surviving literary manuscript, British Library

- Shakespeare, Sir Thomas More and the refugee migrants, Shakespeare Blog 2015

supporting documents

- ^ Collection Items, British Library

- ^ After Walter Wilson Greg (Ed.): The Book of Sir Thomas More, The Malone Society 1911, pp. 76, 78

- ↑ Since the manuscript was poorly restored in the following years, some parts of the text published by Dyce in 1844 are no longer legible today

- ^ Thompson, Shakespeare's Handwriting: A Study, Oxford University Press 1916

- ^ For example, Paul Ramsay: The literary evidence for Shakespeare as Hand D in the Manuscript play Sir Thomas More: a re-re-consideration , The Upstart Crow, Volume 11, 1991, pp. 131-135, Paul Werstine, Shakespeare More or Less: AW Pollard and Twentieth-Century Shakespeare Editing , Florilegium, Volume 16, 1999, pp. 125-145 (on this EAJ Honigmann , Shakespeare, Sir Thomas More and Asylum Seekers , Shakespeare Survey, Volume 57, 2004, pp. 225-235 )