Slavery by Another Name

Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (translated: slavery under another name: The Wiederversklavung Black Americans from the Civil War to the Second World War ) is a 2008 published non-fiction of the American writer Douglas A. Blackmon , who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 2009.

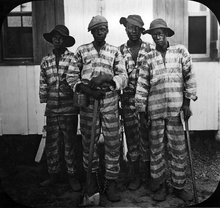

Slavery by Another Name addresses the forced labor of imprisoned black men and women through so-called convict leasing , in which prisoners were leased to private individuals or companies for a fee or served their sentence in the form of debt bondage . Individual states, county governments, justice of the peace, white farmers and companies were involved. Since this form of serfdom can be proven from the end of the American Civil War until well into the 20th century, Blackmon argues that the American Civil War did not end slavery in the United States.

Blackmon first dealt with the subject of forced labor by blacks in an article for The Wall Street Journal using the example of US Steel . Due to the very extensive reactions to the article, he began to research the topic in more depth. The non-fiction book created on the basis of this research was included on the bestseller list of The New York Times Book Review and was the basis of a documentary film for PBS in 2011 .

background

Blackmon is a reporter for the Wall Street Journal . He grew up in Washington County, Mississippi , where as a seventh grader, encouraged by his teacher and mother, he researched a local incident of racism for a history essay. Despite negative reactions from some adults to his research work, according to his own statements, this justified a continued interest in the relationship between whites and colored people in US history.

In 2003 Blackmon described the use of black slave labor in the US Steel coal mines in an article. The article met with a wide response and was included in an anthology of the best economic articles in 2003. Blackmon then began to conduct extensive research on the subject. Originally, he wanted to tell the life story of Green Cottenham, who was arrested and convicted in 1908 on the basis of a presumably fabricated accusation of vagrancy, who had to do forced labor under the convict lease system in a US Steel coal mine and was killed in the process. However, Blackmon was unable to find sufficient sources on the case. In the course of his research, however, he noticed the numerous arrests and convictions of blacks, suggesting that there were numerous cases comparable to Green Cottenham's.

content

In the introduction to Slavery by Another Name , Blackmon refers to German companies that have to be asked to what extent they profited from Jewish forced labor during the rule of National Socialism, and suggests that a number of US companies in a comparable form of black forced labor benefited.

Blackmon proves that in the decades after the end of the American Civil War, black people were not only used for forced labor in cotton fields, but also in factories and especially in mines. Although slavery was formally abolished with the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1865, the southern states issued a series of so-called black codes in the decades that followed, which were essentially aimed at criminalizing people of color, making them socially insecure, and white supremacy to be fixed. These black codes also provided the pretext for sentencing people of color to several months' imprisonment on the basis of banal and often fabricated allegations. They were then rented out to plantations, sawmills and mines for forced labor or were ransomed by private individuals and companies on payment of a bail, provided they were willing to sign a bondage contract at the same time . This left them vulnerable to living conditions that were harsher than those that enslaved people experienced before 1860. While slave owners had an economic interest in maintaining the labor of their slaves, this incentive did not exist for the slave laborers. Inadequately supplied with food and clothing, chained and regularly subjected to corporal punishment, the death rate of prisoners in bondage or rented out through a convict lease system was extremely high. One case cited by Blackmon is that of John Clarke, who was fined April 11, 1903 by a Jefferson County court for gambling. Unable to pay the fine, he was rented to the Sloss Sheffield mine, where he would have served his sentence after ten days of work. Additional fees imposed on him as part of the legal process added 104 days to his forced labor. The Sloss Sheffield Mine paid $ 9 a month for the Jefferson County labor. However, John Clarke did not see the end of his forced labor: He was killed after a month and three days by falling rocks. Blackmon mentions numerous other cases in which inmates who had finished their term of imprisonment or the length of their bondage were sentenced to further forced labor on trumped-up charges. Justice of the peace, sheriffs and employees of the districts benefited financially from providing those interested with such forced laborers.

Blackmon also points out, however, that it was the death of a leased white prisoner in 1922 that made the cruelty of this system so clear to a very broad public in 1922 that the practice of convict leasing was finally discontinued in the following years. In the winter of 1921, Martin Tabert, a 22-year-old white man from a middle-class farming family in North Dakota, decided to travel to the United States. He traveled the West and Midwest by train, working in between to finance his trip. In December 1921 he had arrived in the southern states and, running out of funds, he jumped on a freight train with a group of other hobo men. You were picked up by the local sheriff in Leon County, Florida . Tabert was fined $ 25 for vagrancy and then leased for three months to the Putnam Lumber Company, which was producing turpentine from wood in labor camps. Tabert's family had sent enough money to redeem their son within days, but Tabert had already gone missing in the Putnam Lumber Company labor camps. He did not endure the brutal labor conditions in the labor camp for long. In January 1922, camp manager Walter Higginbotham accused Tabert, who fell ill, of work shyness. He was forced to lie on the floor in front of the assembled 85 other convicts to receive 35 lashes on his bare back with a leather thong. When Tabert was unable to get up afterward, he received an additional 40 blows and an additional 24 blows for moving too slowly to his bed. Tabert died the next night. A few days later, a senior executive at the Putnam Tumber Company wrote to Tabert's family that their son had died of malaria. The family initiated a prosecutor's investigation into the incident and journalists investigated, which ultimately resulted in a Pulitzer Prize- winning article in New York World . Higginbotham was convicted of manslaughter, but his conviction was later overturned by a Florida court. The death, which made it clear that the excesses of criminal prosecution practiced in the southern states could extend to whites from respected families, was widely discussed in the US public. He immediately ensured that the use of the whip against prisoners was prohibited in Florida.

The problem of illegal debt bondage became known to a wider audience through a spectacular murder case. In 1921, the plantation owner John S. Williams and his overseer Clyde Manning reportedly murdered at least 11 black workers who were under bonded labor contracts. Williams feared prosecution for debt bondage after being visited by FBI agents, but in his first interview with agents described bondage as a common (if illegal) practice in the area. Presumably, the FBI agent's visit would have been of no consequence to Williams if the decaying bodies of the murdered had not appeared in the waters of Jasper County, Georgia weeks later . Debt bondage can be proven up to 1941. On October 13, 1941, Charles E. Bledsoe pleaded guilty in federal court in Mobile, Alabama, to having detained a black man named Martin Thompson against his will on the basis of a debt servant contract. Bledsoe was fined $ 100 and sentenced to six months probation.

State attorneys such as Warren S. Reese attempted to end this practice using federal anti- debt bondage laws as early as the early 1900s, but received no regional or national support in these efforts. The system of convict leases or debt bondage in its various forms did not end until the outbreak of World War II, when the need for national unity came back into focus.

reception

In a 2008 review for the New York Times , Janet Maslin wrote that Blackmon's book was undermining one of America's core beliefs: that slavery in the United States ended with the American Civil War. She gives him credit for having brought back a previously largely neglected aspect of American history. A similar judgment is made by Leonard Pitt, who called Slavery by Another Name an astonishing book that dramatically changes one's understanding of history.

James Smethurst, a historian specializing in African American history, calls Slavery by Another Name a compendium on the end of Reconstruction , the attempt to reshape the slavery-dependent southern states. However, Smethurst calls the abundance of examples one of the book's weaknesses. He also complains that Blackmon did not adequately differentiate between the convict lease system and debt bondage. Blackmon had also neglected the numerous testimonies to forced labor and bonded labor that can be found in African American literature. However, he also points out that the book illustrates the scope and horror of this form of modern slavery.

literature

- Douglas A. Blackmon: Slavery by Another Name: The re-enslavement of black americans from the civil war to World War Two , Icon Books, London 2012, ISBN 978-1-84831-413-9

Single receipts

- ↑ Blackmon: Slavery by Another Name . 2012, p. 404 and p. 405.

- ↑ PBS Introduction to Documentation Based on Blackmon's Film , accessed December 28, 2013

- ↑ Interview with Blackmon in MPRNews , accessed December 28, 2013

- ↑ Interview with Blackmon in MPRNews , accessed December 28, 2013

- ↑ Blackmon: Slavery by Another Name , 2012, p. 39

- ^ Blackmon: Slavery by Another Name , 2012, p. 53

- ↑ Blackmon, 2012, p. 112

- ↑ Blackmon: Slavery by Another Name. 2012, p. 366.

- ↑ Blackmon: Slavery by Another Name. 2012, p. 367.

- ^ A b Blackmon: Slavery by Another Name. 2012, pp. 363-367.

- ↑ Blackmon: Slavery by Another Name. 2012, p. 363.

- ^ Blackmon: Slavery by Another Name , 2012, p. 377 and p. 378.

- ↑ Review of the book in the New York Times, April 10, 2008 , accessed December 28, 2013

- ↑ Review of the book in the Baltimore Sun, July 28, 2008 , accessed December 28, 2013

- ↑ James Smethurst's review of the book on June 22, 2008 , accessed December 28, 2013