Temple economy

In Assyriology and Near Eastern Archeology , temple economy describes, among other things, a historical thesis, according to which every economic activity in Sumerian Mesopotamia was oriented towards the temples . This, state capitalist ' economic system is the theocratic sprung basic idea that the whole community a deity or gods family is intrinsically than full ownership, from ensik would Priest the prince of the respective city state represented. The relationship between the deities and their earthly governors thus corresponded to that between landlords and land managers.

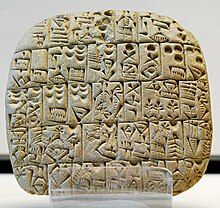

The thesis was developed at the beginning of the 20th century after texts that could be interpreted in this way had been found in Tello (today Girsu ), which date back to the 24th century BC. To be dated. Based on the oldest described clay tablets from the temple area of Uruk , which also came from the context of an economic administration, it was assumed that the temple economy in Mesopotamia had existed since the 4th millennium BC. Was a universal phenomenon.

This assumption came under increasing criticism towards the end of the 20th century, if not gone away. Archaeological finds indicate clear signs of private economic activity or the complete lack of centralized temple and economic districts in other settlements, as well as a clear separation between administrative officials and cult figures. A further point of criticism is of a research systematic nature, in that it is noted that the previous selection of central settlements as preferred excavation sites inevitably led to the misleading impression of centralized forms of organization.

In pharaonic Egypt , temples of gods and mortuary temples were the decisive economic redistribution centers. In the Old Kingdom and partly also in the Middle Kingdom , the economic and cultural unification of Egypt was intertwined with the role of the pyramid building . The royal residence, together with the mortuary temple, was near the pyramid city, where goods from all districts and provinces were brought together and redistributed. In the New Kingdom and in the late period, the great temples of gods, especially in Thebes and Memphis , were the economic, administrative and redistributive centers.

Similar, if not so pronounced manifestations of intensive economic interdependence of religious centers and the people working in them (“temples”, “priests”), for example in ancient Greece or India, are sometimes also referred to by the term temple economy. In the historical biblical studies the economic and fiscal function and importance of the Jerusalem temple in biblical times is examined under this heading .

literature

- Hans J. Nissen : History of ancient Near East . R. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-486-56374-2 , pp. 156-159.

Individual evidence

- ^ Thomas Naumann: Trade / Traders (AT). In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (eds.): The scientific biblical dictionary on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff., Accessed on January 3, 2020. Section “2.3.3. Internal Trade ", below (as of October 2012). See also: Joachim Schaper , Michael Tilly : Tempel. In: Frank Crüsemann , Kristian Hunger, Claudia Janssen , Rainer Kessler , Luise Schottroff (eds.): Social history dictionary for the Bible. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2009, ISBN 978-3-579-08021-5 , pp. 581-586.