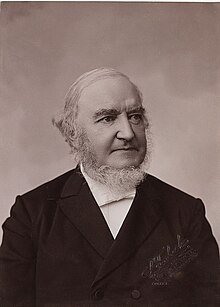

Torkel Halvorsen Aschehoug

Torkel Halvorsen Aschehoug (born June 27, 1822 in Idd (now Halden ), † January 20, 1909 in Kristiania ) was a Norwegian lawyer, social economist, historian and politician. He was the type of professor politician of the time.

Family and youth

His parents were: Pastor Halvor Thorkildsen Aschehoug (1786–1829) and his wife Anne Christine Darre (1799–1885). In his first marriage he married his cousin Anne Catharine Marie Aschehoug (1822-1854), daughter of the pastor Johan Aschehoug (1795-1867), brother of Halvor Thorkildsen Aschehoug, and his wife Marthe Elisabeth Joys (1799-1863). In his second marriage in 1856 he married the sister of his first wife Johanne Bolette Aschehoug (1832-1904).

Aschehoug grew up in a pastor's family. Father and grandfather were pastors and also members of the Stortings. After his father's death, he lived with his grandfather. In 1839 he passed the exam artium. He studied law at the University of Christiania and was cand. Jur. In the course of his studies he joined the intellectual circle Intelligensen around Anton Martin Schweigaard . Throughout his career he was part of the academic and political elite.

The politician

He entered politics early and belonged to the Høyre party . He was also a central contributor to the Morgenbladet newspaper for 20 years from 1847 to 1868 . Like many intellectuals of his time, he was a member of Det skandinaviske selskap . As a leading member of the second union committee (1865-1867), as a supporter of Scandinavianism, he was significantly involved in the drafting of a new union treaty between Norway and Sweden. On the one hand, the draft was intended to ensure that Norway had an equal position with Sweden within the Union, and, on the other, to connect economic and political ties more closely. But the draft was not accepted because the political public saw it as a weakening of Norwegian independence within the Union.

In 1868 Aschehoug became a member of parliament in Storting . He attended all the meetings until 1882. His program was linked to the government's policy: reform policy within the framework of the constitution. He worked closely with Frederik Stang . After Schweigaard's death, many saw him as the right successor. But the expectations did not materialize. Although he showed extensive knowledge in his sorting work, he did not have Schweigaard's undisputed authority.

University career

In 1852 he became a lecturer at the law school. In 1862 he became a professor. After Schweigaard's death in 1870, he also took over economics and statistics. His legal focus was public law. But he also dealt with inheritance law and tax law. From 1863 he was often an associate judge at the Supreme Court . In this way he gained experience in the business process and in the practice of this court. As a lecturer, Aschehoug read in 1852 about “Fædrelandets offentlige Ret” (The public law of the fatherland).

Scientific work

At the age of 23, Aschehoug published his first book, Indledning til den norske Retsvidenskab . Here he gave an overview of the Norwegian legal system for the first time. It was important that he worked out the meaning of the constitution for normal legislation and developed a doctrine of the interpretation of the law. He was also the first in Norwegian legal theory to introduce the German “ historical school ” view of the essence of law. The historical view of the law remained decisive for his scientific work.

Research into society and social policy was at the center of Aschehoug's interests until the mid-1950s. He wanted to make the economic theories fruitful for practical life, for example in dealing with the relationship between the state and the individual and the problem of the poor. In addition, he saw the foundation of law in natural law. Study trips strengthened his view of economics as an empirical science . Back in Norway, he continued to study economics and statistics. In 1850 he became a member of the "Husmanns-Wesen" commission and in 1853 of the commission for the poor being in the country. Much of his contribution was to provide statistically validated data for legislation in these areas. He saw economic growth as a tool for solving social problems.

From 1873 he published his main legal work, Norges nuværende Statsforfatning (Norway's current state constitution) in continuous issues . It then appeared in three volumes (1875–1885). In doing so, he built on a pluralistic doctrine of legal sources: the constitutional text was only the starting point for determining the applicable constitutional law. It had to be supplemented from the history of the constitution and state and legal practice, whereby the comparative law with the constitutional problem solutions of other countries had to be included.

Aschehoug saw an independent royal power and limited suffrage as a central feature of the Norwegian constitution. But in the 1970s he realized that parliamentarism and universal suffrage would come. That is why he proposed in the Storting the introduction of a two-chamber system as a conservative guarantee and limitation of a radically democratic form of government. But the Norwegian political reality did not permit such reforms. He was liberal in cultural and science policy and advocated freedom of research. So he defended the Norwegian Darwinists and the full freedom of poetry.

His political stance in the Storting also shines through in his constitutional interpretation, for example when he deals with the conservative understanding of the distribution of power in the constitution and advocates the king's absolute right of veto . A much debated question is to what extent he has contributed to the teaching on the right of the judiciary to review decisions of the Storting for their constitutionality. After all, he developed this doctrine in 1884 as a conservative counterweight to the loss of the royal right of veto. With this instrument, the conservative Supreme Court could limit the effects of unlimited democratic rule of the Storting.

His historical work also tied in with his economic and legal research. He advocated a positive assessment of the time under Danish rule . This work marked the beginning of a general reorientation of Norwegian historical research in the 1960s. He worked essentially empirically and saw the science of history as an investigation of the causal connections in the development of a constantly advancing civilization. The material conditions in society were essential for this development from an early age.

His main historical work was Statsforfatningen i Norge og Danmark indtil 1814 (The state constitution in Norway and Denmark until 1814), which appeared in 1866. The work contains not only the constitutional history, but also the social history. Nevertheless, he thought the book was a legal work. In doing so, he followed the German legal history school, which saw the importance of legal history and the context of society as a prerequisite for understanding applicable law. This is how he justified the state's supervision of the church and its borders in legal history: the state had supervised the church since the Reformation because it gave collective expression to the religious feelings of society, but it was not able to change the Lutheran creed even under absolutism which does not prevent different currents. He was also influenced by the English economist Alfred Marshall and the German conservative reformist Adolph Wagner , the main architect of Bismarck's welfare state. It is to these influences that the early Norwegian social legislation and the introduction of progressive taxation can be traced back.

He considered the stronger union of Denmark with Norway in 1537 necessary to really rule Norway. Even if the Danish policy towards Norway was flawed, it had brought the goods of civilization to Norway in the long run, the creation of legal certainty being its greatest merit. He was in sharp contrast to his contemporary and colleague Ernst Sars , who referred to this time as the “400-year night”, and other nationalists who wanted to tie Norwegian society back to the old royal days and skip the 400-year history as a Danish province .

From the mid-1980s until his death, social economy was the focus of his interest. A separate chair had already been established for this in 1877, which he took over in 1886. As early as 1883, a Statsøkonomisk forening (National Economic Association) was founded on his initiative, and he was chairman until 1903.

In 1887 the Statsøkonomisk Tidsskrift (Journal of Economics) was created, where he published 15 large articles. After 1900 his main socio-economic work, Socialøkonomik, appeared . It dealt in three volumes (the third volume in two half-volumes; 1903-1908) the economics of human society. It presents analyzes of social institutions and economic theories. The historical view is central and is incorporated into the presentations partly as a theoretical history, partly as an economic history, and partly as an event history. He knew about the latest theories and was involved in the introduction of the theory of marginal utility according to the Austrian school into the Norwegian technical discussion, which was first made known in Norway through Oskar Jæger's dissertation on Adam Smith in 1892, which described the marginal utility theory .

Aschehoug was admitted to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1890 and was awarded the Order of Saint Olav (Grand Cross) in 1895 . The University of Lund awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1868 and the Albertus University of Königsberg in 1892 . In 1908 he received Norway's highest civilian award, the Borgerdåds medal in gold. After him was Professor Aschehougs plass named in Oslo.

Works

- Indledning til den norske Retsvidenskab . (Introduction to Norwegian Law) 1845.

- Norges public ret. Første Afdeling. Statsforfatningen i Norge og Danmark indtil 1814 . (Norway's Public Law. First Section. Constitution of Norway and Denmark until 1814). 1866

- Om Union Committees Udkast til en Foreningsakt . (On the draft of the Union Committee for a Unification Treaty). 1870

- Norges public ret. Andes afdeling. Norges nuværende Statsforfatning (Norway's Public Law. Second Section. Norway's Current Constitution) (3 volumes. 1874–1885; 2nd edition 1891–1893)

- Nordisk retsencyklopædi (Norway's Legal Encyclopedia ) (together with KJ Berg and AF Krieger). 5 volumes, Copenhagen 1885–1899; in volume 1 (1885): "Den nordiske Statsret" (the Scandinavian constitutional law)

- Statistiske Studier over Folkemænge og Jordbrug i Norges Landdistrikter i det syttende og attende Aarhundrede (Statistical studies of the population and agriculture in Norway's rural districts in the 17th and 18th centuries). 1890

- De norske Communers Retsforfatning for 1837 . (The legal constitution of the Norwegian municipalities before 1837). 1897

- Social economics. En videnskabelig Fremstilling af det Menneskelige Samfunds økonomiske Virksomhed . (Social economy. A scientific representation of the economic conditions of human society) 3 volumes in 4 books, 1903–1908 (2nd edition of volume 3: 1910)

Remarks

The article is essentially based on the Norsk biografisk leksikon . Any other information is shown separately.

- ↑ The Examen artium was the entrance examination for the university, so it corresponded to the Abitur, but was accepted by the university.

- ↑ cand. Jur. was the "examined legal candidate", so had passed the state examination.

- ↑ Aschehoug: Norges nuværende Statsforfatning . 2nd Edition. Volume 3, Kristiania 1893, p. 2 f. and p. 7, and volume 1, Kristiania 1891 p. 75 f.

- ↑ "Husmann" was a tenant, small farmer, kätner who cultivated a certain area on the land of a large farmer in return for a fee or compulsory service. Its economy was not hereditary.

- ↑ Aschehoug: Norges nuværende Statsforfatning . 1st edition. Christiania 1874-1885, pp. 299-307.

- ↑ T. Bergh, TJ Hanisch: Vitenskap og Politikk (science and politics). Oslo 1984, p. 94.

- ↑ Knut Mykland: Firehundreaarig natten . In: Historisk Tidsskrift . (Danish), Volume 15, Series 1 (1986) Issue 2. pp. 225-237.

- ^ Oskar Jæger: The modern Statsøkonomis grunnleggelse ved Adam Smith . In: Statsøkonomisk Tidsskrift , 1901.

literature

- Torkel Halvorsen Aschehoug . In: Bernhard Meijer (Ed.): Nordisk familjebok konversationslexikon och realencyklopedi . 2nd Edition. tape 2 : Armatoler – Bergsund . Nordisk familjeboks förlag, Stockholm 1904, Sp. 138 (Swedish, runeberg.org ).

- Dag Michalsen: Torkel Halvorsen Aschehoug . In: Norsk biografisk leksikon ; Retrieved October 25, 2009.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Aschehoug, Torkel Halvorsen |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Norwegian lawyer, economist, historian and politician, member of the Storting |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 27, 1822 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Halden , Norway |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 20, 1909 |

| Place of death | Oslo , Norway |