Bald eagle

| Bald eagle | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bald eagle ( Haliaeetus leucocephalus ) |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||

| Haliaeetus leucocephalus | ||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1766) |

The bald eagle ( Haliaeetus leucocephalus , from Greek ἁλι- hali- "sea water- ", αἰετός aietos "eagle", λευκός leukos "white", κεφαλή cephale "head") is a large bird of prey from the Accipitridae family . In appearance and way of life, the species is very similar to the Eurasian sea eagle , the two species are therefore united by some authors to form a superspecies . The bald eagle is the heraldic bird of the USA and can therefore be seen on their seal .

The stocks of the bald eagle, which was originally found in large parts of North America, have been declining since the 19th century, with the lowest number of breeding pairs recorded in the 1960s. The reasons for this were kills, the consequences of the use of DDT and changes in habitat. The first legal edicts to protect the bald eagle were issued in the early 20th century, which were tightened in the following years. After the ban on DDT, which through biomagnification had a major impact on the ability of bald eagles to raise offspring, stocks recovered. Bald eagles can now be found again in their entire original range and the populations have recovered to such an extent that they are no longer considered endangered.

description

Bald eagles are the largest birds of prey in North America after the California condor . Their body length is 70–90 cm, the wingspan 1.80–2.50 m and the weight 2.5–6.3 kg. The proportions and plumage are very similar to the sea eagle , but the coloration of the bald eagle is much more contrasting. The head and the neck, the tail and the lower and upper tail-coverts are white, the body and wings are dark brown. Feet, beak, wax skin and the iris of the eyes are light yellow.

The fledgling juveniles are very similar to the young birds of the sea eagle, they are brown with a dark gray beak and brown iris. The best distinguishing features to the young sea eagle are the white axillary feathers and the largely unspotted belly. They do not reach sexual maturity until they are five and sometimes six years old. It is very rare that they are fully grown by the age of four, and in exceptional cases they reach sexual maturity as early as three years. They develop the plumage that corresponds to that of adult birds over several years: two-year-old bald eagles have gray-brown or whitish eyes. The belly and back appear spotted with white. In three-year-old bald eagles, the cheeks and head already show a greater proportion of white, the beak is yellow. The irises of the eyes are now light yellow. Bald eagles in their fourth year of life already predominantly have a dark brown body and dark brown wings, but there are still individual white spots. The tail as well as the lower and upper tail-coverts are already white in most individuals. The head is white, but still has a dark streak of eyes.

distribution

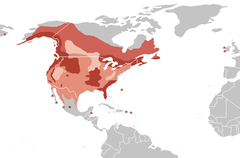

Originally, the bald eagle was common all over mainland North America . Due to human persecution, the distribution in the USA is now essentially reduced to the east and west coasts as well as to Alaska , and the species colonizes large parts of Canada . The bald eagle lives mostly on rivers, lakes or on the coast. The largest population is in Alaska, the second largest in Florida, with Florida 70% living on the St. Johns River . It is sometimes found in central Arizona and in the Gulf of Mexico. During the winter months, the bald eagles, which are found in the northern range, congregate in certain regions. Between November and February, between one and two thousand bald eagles arrive near the town of Squamish in the Canadian province of British Columbia, at the northern end of Howe Sound . They stay along the banks of the Squamish and Cheakamus Rivers due to the salmon returning to their spawning grounds . The bald eagle has been seen twice in Europe as a stray visitor . A juvenile was illegally shot down in County Fermanagh, Ireland in January 1973 , and an exhausted juvenile was found in County Kerry, Ireland in November 1987 .

nutrition

Similar to the sea eagle, the bald eagle feeds mainly on fish and waterfowl, and it uses mammals less often as prey. In 20 studies of the bald eagle's eating habits, fish made up a total of 56% of the diet of nesting birds. Birds provided 28% and mammals 14% of the diet; other prey animals accounted for 2%. In southeast Alaska, the bald eagle's diet consists of 66% fish, while fish accounts for 78% of the prey they bring to the nest during the nesting season.

It often eats carrion, especially in winter. Like the white-tailed eagle, the bald eagle often parasitizes other species. The hunting methods largely correspond to those of the sea eagles.

Reproduction

Like the sea eagle, he builds the nests (clumps) on old trees or in rock walls from thick branches, the hollow is padded with moss and grass. Old clumps can weigh up to 450 kg. The clutch comprises one to three eggs and the incubation period lasts 33–36 days. The young eagles can fledge after ten to eleven weeks.

Lifespan and causes of mortality

In the wild, the average lifespan of bald eagles is around 20 years, with an age of 28 years for a single individual. In captivity, they regularly reach a higher age. An individual kept in New York lived nearly fifty years of age.

The average lifespan that is reached in a population of bald eagles is largely influenced by the availability of food and thus in turn by the region in which they live. Since they are no longer tracked, the adult bald eagle death rate is extremely low. In Prince William Sound , Alaska, they had an annual survival rate of 88% even after the Exxon Valdez's wreck resulted in serious oil pollution. Of 1,428 individuals whose cause of death was investigated by the National Wildlife Health Center between 1963 and 1984, however, 68% died directly or indirectly from human influence. 23% of the causes of death were due to collisions with vehicles or wires, 22% died from shooting down, 11% from poisoning, 9% from electric shock and 5% in traps. However, it is assumed that the number of illegal kills due to the threat of punishment has meanwhile decreased.

As a rule, less than 50% of the nestlings survive their first year of life. The collapse of the nest, starvation, aggressiveness and unfavorable weather conditions contribute to the high mortality rate, which is not atypical for bird species. Another major reason for egg loss and nestling death are predators . The predators include large species of seagulls , ravens, crows and magpies , wolverines , other birds of prey such as owls , hawks and eagles, lynxes , brown bears and raccoons . Parent birds vigorously defend their nest against predators and have even successfully repelled an attempt by a brown bear to climb a tree on which there were nestlings.

Hazard and protection

Stock decline until the 1960s

Originally a comparatively common North American bird of prey, the species was exterminated in large parts of North America by 1950. In the 1950s and 1960s there was a further decline in the population, which was mainly attributed to the use of the pesticide DDT . Bald eagles, like many birds of prey, are particularly susceptible to pollutants building up in their bodies through food. This so-called biomagnification with DDT was not fatal for the adult bird, but it did affect its calcium metabolism and ultimately resulted in the bird either being sterile or unable to lay healthy eggs. Females laid eggs that were too thin-skinned to support the weight of a brooding adult bird. As a result, nestlings hardly hatched from eggs.

It is believed that in the early 18th century the bald eagle population was 300,000 to 500,000 individuals. In 1917 a shooting bonus was offered to the bald eagle. As early as 1940, shooting was banned again in the southern states of the USA. In Alaska, the shooting continued until 1953. By the late 1950s, there were fewer than 500 breeding pairs in the 48 US states that were originally part of the range. Factors that contributed to this development included loss of suitable habitat and legal and illegal degrees. As early as 1930, a New York ornithologist recorded that in the US state of Alaska alone, around 70,000 bald eagles had been shot in the previous twelve years. Many kills were due to the misconception that bald eagles would hunt young lambs and could carry off children themselves. In fact, lambs are rarely hunted by bald eagles and hunting of humans by these bird species is considered to be ruled out.

Protective measures

Measures were taken very early to protect the bald eagle. In Canada and the United States, it was already protected by the 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty , which was later extended to the entire North American territory. In 1940, the US Congress approved the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act , which made commercial catching and killing of bald eagles and golden eagles a criminal offense. Changes to the law enactment between 1962 and 1972 increased the penalties for violations. A decisive step that led to the recovery of the population is the DDT ban in the United States, which was enacted in 1972. Canada did not go quite as far in its decrees - its use was drastically restricted from the late 1970s and was not completely banned until 1989.

Stock recovery

Due to legal measures and the DDT ban, the population of bald eagles recovered from the 1980s. At the beginning of the early 1980s, the population was estimated at 100,000 individuals and in 1992 at 110,000 to 115,000. In 1984, the National Wildlife Federation named hunting and death by power lines as the primary causes of mortality for this bird of prey. Other causes included oil pollution and lead and mercury poisoning.

The US state of Alaska has the largest population with 40,000 to 50,000 individuals. This is followed by the Canadian province of British Columbia , in which 20,000 to 30,000 individuals lived in 1992. The number of adult, breeding bald eagles that breed in a US state other than Alaska was given as 9,789 breeding pairs in 2006. For a long time Florida was considered the state with the most breeding pairs after Alaska. In the meantime, however, it has been replaced by Minnesota , where in 2011 1312 breeding pairs were counted. More than 23 states now have at least 100 breeding pairs each.

The species was one of the key species for the enactment of the Endangered Species Act in 1973 . Due to the protective measures and the gratifying recovery of the population, the species was released from protection under the Endangered Species Act on June 4, 2007. Live and dead bald eagles and their body parts may continue to be owned only with permission in the United States. This also applies to Indians who use eagle feathers for religious and cultural purposes. The National Eagle Repository in Denver , Colorado is granting the permits and making the bodies of animals found dead available to authorized persons.

Detention in the US and Canada

The captivity of bald eagles in the United States requires a separate permit. These permits are given primarily to zoological gardens and mostly bald eagles, which cannot be released into the wild due to injuries, are held. Permits are also granted to individual Indian peoples in North America, where captured bald eagles play a special role in religious ceremonies. In principle, the keeping of bald eagles for falconry is prohibited in the United States; in Canada, however, this is possible with an appropriate permit.

Bald eagles kept in ideal conditions have been shown to be very long-lived. However, they only very rarely brood.

literature

- Jonathan Alderfer (Ed.): Complete Birds of North America . National Geographic, Washington DC 2006, ISBN 0-7922-4175-4 .

Web links

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus in endangered species red list of the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed on December 18 of 2008.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Haliaeetus leucocephalus in the Internet Bird Collection

Single receipts

- ↑ a b c J. del. Hoyo: Handbook of the Birds of the World , vol. 9 . Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2004, ISBN 84-87334-69-5 .

- ↑ Jonathan Alderfer (Ed.): Complete Birds of North America . Pp. 132-133.

- ↑ Website on the observation sites for bald eagles (English) , accessed on May 10, 2015

- ^ AP report from 1987

- ^ "Bald Eagle Fact Sheet, Lincoln Park Zoo" . Accessed May 10, 2015.

- ^ MV Stalmaster; The Bald Eagle . Universe Books, New York 1987.

- ^ Armstrong, R .: The Importance of Fish to Bald Eagles in Southeast Alaska: A Review (PDF) US Forest Service. Archived from the original on November 23, 2014. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ↑ Cornell Lab of Ornithology , accessed May 10, 2015

- ↑ Bald Eagle Fact Sheet . Southern Ontario Bald Eagle Monitoring Project. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ^ TD Bowman; P, F. Schempf; JA Bernatowicz (1995): Bald Eagle survival and populations dynamics in Alaska after the Exxon Valdez oil spill . Journal of Wildlife Management 59 (2): 317-324., 1995. doi: 10.2307 / 3808945 .

- ^ PB Wood, DA Buehler, and MA Byrd: Raptor status report-Bald Eagle . Pages 13 to 21 in Proceedings of the southeast raptor management symposium and workshop . 1990, National Wildlife Federation Washington, DC

- ^ JD Fraser: The impact of human activities on Bald Eagle Populations-a review . Pages 68 to 84 in The Bald Eagle in Canada . White Horse Plains Publishers Headingley, Manitoba 1985

- ↑ Drexel University on the habitat and habits of the bald eagle , accessed May 10, 2015.

- ^ RJ Hensel and WA Troyer: "Nesting studies of the Bald Eagle in Alaska". Condor 66 (4), 1964: pp. 282-286. doi: 10.2307 / 1365287 .

- ↑ A. Sprunt; FJ Ligas; Excerpts from convention addresses on the 1963 Bald Eagle report . Audubon 66, 1964: pp. 45-47.

- ↑ RW Mckelvey; DW Smith: A black bear in a Bald Eagle nest . Murrelet 60, 1979: A. 106.

- ^ C. Nash; M. Pruett-Jones; GT Allen: The San Juan Islands Bald Eagle nesting survey . In RL Knight .; GT Allen; MV Stalmaster; CW Servheen: Proceedings of Washington Bald Eagle Symposium . Seattle, WA, 1980: The Nature Conservancy. Pp. 105-115.

- ↑ JM Gerrard and GR Bortolotti: The Bald Eagle: haunts and habits of a wilderness monarch . Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, 1988.

- ↑ Bald Eagle attacks Black bear again at Redoubt Bay on YouTube

- ^ A b J. Bull, J. Farrand: Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds: Eastern Region. Alfred A. Knopf. New York, 1987, ISBN 0-394-41405-5 , pp. 468-9.

- ↑ American Eagle Foundation website on bald eagles ( December 6, 2007 memento on Internet Archive ), accessed May 9, 2015.

- ↑ DDT ban, EPA website ( memento of July 5, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on May 9, 2015

- ↑ Jorge Barrera: Agent Orange has left deadly legacy Fight continues to ban pesticides and herbicides across Canada ( Memento of January 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on May 9, 2015

- ↑ American Eagle Foundation website on bald eagles ( December 6, 2007 memento on Internet Archive ), accessed May 9, 2015

- ↑ Bald Eagle Breeding Pairs 1963 to 2006 . US Fish & Wildlife Service. March 18, 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ↑ Center for Biological Diversity , accessed May 9, 2015.

- ↑ Bald Eagle Soars Off Endangered Species List . US Department of the Interior. June 28, 2007. Archived from the original on July 13, 2007. Retrieved on August 27, 2007.

- ^ John R. Maestrelli: "Breeding Bald Eagles in Captivity". The Wilson Bulletin 87 (I), March 1975: pp. 45-53.