Xiangqi

Xiangqi ( Chinese 象棋 , Pinyin xiàngqí , W.-G. hsiang 4 -ch'i 2 ; ), Chinese chess , is a form of chess that is widespread in East Asia, especially in China , Taiwan and Vietnam has existed since the 9th century .

General

Xiangqi (Vietnam: Cờ tướng ) is closely related to the Korean chess Janggi . In contrast, the Mongolian Shatar is more similar to Western chess, although it is on the list of the intangible cultural heritage of the People's Republic of China .

As a widespread far, but somewhat controversial theory is that all chess games have a common ancestor - that of India originating Chaturanga - and are therefore related to each other, chess and Xiangqi are similar in many respects. According to another theory, Chaturanga is derived from an older version of Xiangqi. The spread and use of elephants and the setting up at the beginning of a battle speak against it.

The game is played on the intersection of a board with ten horizontal rows and nine vertical lines (90 possible positions). As in Go , the figures are placed on the intersection of the lines, not in the interior of the fields. Accordingly, there are no white and black fields.

Rules of the game

Basic concepts and goal of the game

The game board (which in China can often simply be a fold-out paper game board) is divided into special areas. Between the 5th and 6th row is the " yellow river " without longitudinal lines, which divides the playing field into two realms - north (red) and south (black). This flow affects how two types of figures move.

The general (king) himself and his companions, the bodyguards (mandarins) are also restricted in their movement. You can not leave the palace or the fortress (an area of 3 by 3 fields (intersections) in the middle of the basic row, which is marked by diagonal lines). Not infrequently it happens that one of the or even both mandarins becomes a “traitor” to their general, because they restrict his movement so that he no longer has a place to escape.

The game pieces are not figures, but rather thick, round disks that are distinguished by their printed, painted or embossed Chinese characters . Although the pieces on both sides do not differ from one another in their moves, two different, but either meaning-similar or identical ( homophonic ) characters (one for red, one for black) are used for each type of figure. This is due to the fact that the black stones (sometimes also green) represent the southern Chinese, while the red stones represent the northern Chinese; a possible - albeit unproven - explanation is that because of the different dialects of the two parts of the country, and because the north z. B. did not have war elephants, the names are partly different. In old game sets, which often only use carved characters without black and red coloring, all pairs of figures are labeled slightly differently in order to be able to distinguish the stones without color marking.

One player leads the red stones, the other the black ones. Red opens the game with the first move.

In Chinese chess, players always hit at the destination of a move. If a pawn can reach a point with its move that is occupied by an opposing pawn, this can be captured and is removed from the playing field. There is no need to hit .

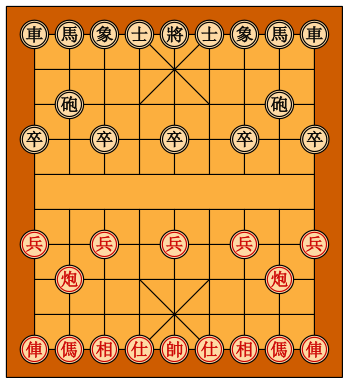

Starting grid

On the basic row from left to right:

- Chariot / 車 jū (black and red)

- Rider (red) - horse / 馬 mǎ (black and also red)

- Minister / 相 xiàng (red) - elephant / 象 xiàng (black)

- Bodyguard / Officer / 仕 shì (red) - Mandarin / 士 shì (black)

- Feldherr / 帥 shuài (red) - General / 將 jiàng (black)

- Bodyguard / Officer / 仕 shì (red) - Mandarin / 士 shì (black)

- Minister / 相 xiàng (red) - elephant / 象 xiàng (black)

- Rider (red) - horse / 馬 mǎ (black and also red)

- Chariot / 車 jū (black and also red)

Two rows facing the river, in front of the riders or horses, two cannons / 炮 pào (red) and catapults / 砲 pào (black) on each side. On the next row there are five soldiers / 兵 bīng (red) and infantry / 卒 zú (black) on each side; These are, starting with one edge field, on every second field to the other edge. The starting spaces of the cannons and soldiers are highlighted on most game boards and boards by markings at the intersection points (hidden in the picture).

In the picture, as with (traditional) Chinese maps, south (black) is at the top.

Train rule

The general

The commander (red) and the general (black) - both also called king by western players - only ever move one step horizontally or vertically (not diagonally) to an immediately adjacent space. He is never allowed to leave the palace (the fortress), so he only has nine spaces in total that he can enter. A castling does not exist.

The two opposing generals may never face each other freely on a line without a piece in between. The general's “death look” forbids this and thus introduces an interesting (but double-edged) long-range effect for the general who is reluctant to travel, which can be used especially in the endgame to force a stalemate (which in Xiangqi is not a draw, but a victory).

According to legend, this figure was once called "King" in China, but this is said to have been forbidden by an emperor, as he felt offended by being pushed around on a playing field by his subjects.

Bodyguard

The mandarins / officials (red) and bodyguards (black) have the same origins as the queen of European chess, but are much weaker than this: They only move one step diagonally (not horizontally or vertically) onto an immediately adjacent square and are allowed to enter the palace also do not leave. This means that both of them have only five fields available, namely the middle of the palace and its four corners, on which they can be at all.

Ministers and elephants

The ministers (red) and the elephants (black) (who give the game its name; xiàng = 'elephant') correspond to the elephants of Shatranj ; they are related to the modern runner , but their pulling power is also significantly weaker. Western players usually refer to the figures on both sides as elephants. The elephants always take exactly two steps in a diagonal direction, but only if the space in between (skipped) is free. If there is a piece of your own or someone else's on this space, this move is denied. In addition, the elephants are never allowed to cross the river, i.e. the border between the two realms between the fifth and sixth row. So they have seven fields in common, all in their own half of the field, on which they are allowed to be at all. With the exception of the strong middle position on the front of the palace, you have a maximum of two moves to choose from on all of the other squares, unless one or both of them are blocked by neighboring stones. The elephants are purely defensive figures, but as such, because of their ability to "get around" quickly in their own half, they are much more important than one might assume - due to the lack of runners and women of European style.

Horses

The horses are essentially the same as the knights in European chess, but they cannot jump. A horse first moves one square horizontally or vertically in any direction and then one square diagonally (further away from the starting square), but is blocked if another stone is on the first square to be entered. The strength of the horses increases towards the endgame, because then there are fewer stones that could block them.

dare

The move of the (battle) chariots corresponds to that of the rooks of European chess - they move any number of squares in a horizontal or vertical direction. The chariots are by far the strongest figures. While they cannot fully develop their strength in the opening due to the unfavorable position in the corners and the still relatively full playing field, their strength increases towards the endgame.

Cannons

The cannons are a purely Chinese invention and do not correspond to any figure in European chess or any other form. If they don't hit, they move like carts. For whipping somewhere must be between the stone to be beaten and the gun exactly one other marker is ( ski jump stone ), which is skipped when struck. A striking movement is possible over any distance and in a horizontal or vertical direction. Both your own and your opponent's stones can serve as a jump stone.

This approach of the cannon (more precisely: the mortar and catapult), which at first seems a bit strange, enables many different interesting constellations. The double cannon in particular (a player's cannon that uses the other cannon as a Schanzenstein) is a powerful weapon in the game when aimed at the opposing general. Overall, however, the strength of the cannons tends to decrease towards the endgame because there are fewer and fewer possible hill stones.

soldiers

The weapon (red) and soldiers (black) (or farmers ) know a direction of movement: one space forward - at least until they have crossed the river. If they have reached the opposing side of the river, they are promoted and can not only move forward, but also one space to the left or right, but not diagonally or backwards.

In contrast to western chess , the soldiers do not hit diagonally, but exactly as they usually move, i.e. forwards and across the river also sideways. A double step in the first move (and thus also the en passant capture ) is not possible; but this is compensated for by the starting position further forward.

A conversion on the opposing back row does not take place; a soldier who has arrived there can only pull sideways.

Even if the pawns no longer play a particularly important role as defensive pieces due to their loosened up and forward position in contrast to European chess, they are definitely important offensive pieces, especially since they cannot be simply played through the Can stop in front of another figure. They are also powerful weapons as entrenchment stones for the cannons.

the end of the game

The general is in check when an opposing piece threatens him (could move to his position and thus capture him). It is forbidden to move into chess, and a chess bid by the opponent must be averted in the immediately following move, otherwise the game is lost. The two generals also threaten each other if nothing is in a straight line between them; Moves that create this situation are therefore forbidden like other moves into chess.

Accordingly, there are basically three ways to get out of chess:

- the general pulls out of the chess position

- the threatening opposing counter is captured

- your own token covers the general

- The previous three ways to fend off a chess are the same as in western chess. A peculiarity in Xiangqi arises when the general is attacked by a cannon and the entrenchment stone in between belongs to the player who is in check: then the check can also be canceled by moving this stone between the cannon and the general. Fending off a chess in this way by practically "exposing" the general can take some getting used to and difficult to see for players of western chess.

In contrast to European chess, there is no stalemate in Chinese chess : if a player cannot move, he has lost the game.

The bidding of permanent chess or repetitions to threaten unprotected pieces is prohibited. In this case the attacker has to change his behavior.

A tie by agreement is possible.

notation

There are several types of notation used to record gameplay. In any case, the moves are numbered and written down according to the same pattern:

- 1. <first move> <first answer>

- 2. <second move> <second answer>

- 3. etc.

It is easier to understand, but not necessary, to put each pair of moves on a separate line.

Unfortunately, there are very many variants of the notation in use and you should always check which application of abbreviations or numbering is used.

Classic system

The game board is numbered from right to left with the numbers one to nine on one face of an area - as seen from the respective player. The counting direction is explained by the classical Chinese spelling. In the classic Chinese style, writing a text begins in the upper right corner and continues to write column by column. This type of numbering results in a notation that is identical for both sides. Nobody needs to rethink when the sides are switched. In order to better distinguish the moves of both sides in a recording, one area is numbered with Arabic numerals, the other area with Chinese numerals.

The names of the characters will be written in Chinese characters (cannon is always 炮, horse is always 馬); The direction of movement is indicated by a special sign. Forward moves are marked with mit, backward moves with 退 and side moves with 平. The numbers are written in Chinese for one or both players and in Arabic for the other. For figures that move diagonally (horse, elephant, advisor), the characters 進 or 退 are used instead of 平.

The structure is <Figure> <Start line> 平 <Finish line> for horizontal moves or <Figure> <Start line> <Direction: 進 or 退> <Number of rows crossed> for vertical movements .

Computer programs use a representation with simple characters (see table), which is also used in English-language literature. The abbreviations in the form of “f”, “b” and “h” are also used in the latter.

|

The most common opening sequence is written like this according to this system:

- 1. 炮 二 平 五 馬 8 進 7 or (English) 1. C2 = 5 H8 + 7 or (German) 1. K2 = 5 P8 + 7

Algebraic system

This method is mainly used by western players and in translated books to help the chess player get started. It corresponds to the algebraic notation of the game of chess. Letters are used for lines (a to i) and numbers for rows (1 to 10). Line “a” is on the left from the red player's point of view and row “1” is next from the red player's point of view. This method always designates the fields in the same way, regardless of which player is to move. A 0 is usually used for ten. Sometimes the rows are numbered from 0 to 9.

Figures are written as in the classical system, with the exception that no sign is used for soldiers. Both Chinese characters (less common, corresponds to a figurine notation) and Latin characters (requires a language to be selected) are also used here.

The previous space is only indicated if two pieces of the same kind are allowed to make the move. If the two figures are in the same column, only the row is given. If they are on the same line, only the column is given. If they are neither in the same column nor in the same line, often only the column is given.

Hitting is marked by the "×" character. No marker is used for moves that do not capture a piece. Chess is marked by the sign "+". Checkmate and stalemate are marked by the "#" sign. Trains can also be marked with comment signs like “?” For bad moves and “!” For good moves. (see also chess notation )

The most common opening sequence is written like this using this method:

- 1. 炮 he3 馬 g8 or (English) 1. Che3 Hg8 or (German) 1. Khe3 Pg8

A detailed algebraic notation is also possible. The original field is always specified:

- 1. Ch3 – e3 Hh0 – g8 or 1. Kh3 – e3 Ph0 – g8

Numerical system

A mixture of the classical and algebraic systems is the following. The rows of the board are numbered from 1 to 10, from the closest to the furthest. This is followed by a number from 1 to 9 for the lines, which are counted from right to left. Both details are relative to the player whose turn it is. The start field is bracketed and separated from the target field with a line.

The most common opening sequence is written like this according to this system:

- 1. 炮 (32) -35 馬 (18) -37

Basic concepts of strategy and tactics

Almost all tactical motifs in chess also appear in Xingqi. So are victims , bondage , spit , forks and discovered check possible. There are also mate turns, opening systems, special endgames etc.

| Token | designation | value |

|---|---|---|

| soldier | 1 unit | |

| Soldier after crossing the river | 2 units | |

| Bodyguard | 2 units | |

| Minister / Elephant | 2 units | |

| horse | 4 units | |

| cannon | 4.5 units | |

| dare | 9 units |

These are the usual approximate comparative values, so you can roughly evaluate the effects of an exchange or a position. The value of a figure is very much dependent on the game situation. Horses in particular get stronger in the endgame because the fewer pieces on the board mean that they can no longer be blocked as often. In contrast, the value of the cannon decreases because there are no possible jump stones.

Comparison with other chess variants

| 象棋 Xiangqi basic table |

將 棋, 장기 Janggi basic setup |

international chess basic setup |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

chess

There are important differences that make Xiangqi a game in its own right:

- There are pieces with identical, similar and completely new moves compared to the known chess.

- The game is much more “open” and “comes alive” much faster (shorter opening phase), since the playing field is significantly larger with the same number of figures (which means that the figures are less in each other's way) and the officers do not stand behind an almost impenetrable phalanx of Farmers can hide. There are also many different types of "double attacks" that can be made by the horses and cannons.

- Since there are neither queen nor bishop, the diagonals lose a lot of their importance. In addition, your own figures can cover each other very well through skillful positioning, which makes it difficult for the opponent to attack.

- The playing field is mirror-symmetrical. The general and the general stand exactly in the middle, so that there is no difference between the queen's wing and the king's wing. It is customary to always make the first move on the right wing.

- The presence of explicitly defensive pieces results in completely different tactics and strategies as well as values of the pieces.

- A stalemate does not lead to a draw, but to the winning of the game by the party who is still able to move.

- The two generals (kings) are not allowed to face each other without a figure (their own or someone else's) standing in between ( the evil eye ).

- The goal is to checkmate or mate the opposing general (king).

Janggi

The Korean Janggi lacks the “river” in the middle. The generals also start in the center of their palace instead of the baseline.

Xiangqi in Germany

A team championship has been played since 1992 and an individual championship since 1994. Clubs or regular player meetings can be found in Berlin, Hamburg, Nuremberg, Leonberg, Munich and Steinwiesen (as of May 2020).

The chess grandmaster Robert Huebner is still considered one of the strongest German Xiangqi players, although he never took part in the German players' play. Hübner took part in the 1993 World Championships in Beijing and drew the attention of the Chinese media with his 36th place out of 76 participants. Michael Nägler from Lingen is the German record champion . He won the individual title six times (1996, 1997, 1998, 2000, 2001 and 2007). The Xiangqi community in Germany has adopted the INGO scoring system that was used in the German Chess Federation until 1990 .

photos

See also

literature

- Joachim Schmidt-Brauns: Xiangqi - Introduction to the rules and tactics of the Chinese chess game . Joachim Beyer Verlag, 2019. ISBN 978-3-95920-077-6

- Dieter Ziethen : Xiangqi: Rules and Tactics of Chinese Chess . Hefei Huang Verlag, 2010. ISBN 978-3-940497-28-4

- Vladimir Budde , Thomas Bandholtz: Chinese chess. Game Myth Culture . Joachim Beyer Verlag, Hollfeld 1985. ISBN 3-88805-080-4

- Vladimir Budde : Xiangqi . Admos Media GmbH, 1988. ISBN 3-612-20330-4

- Rainer Schmidt: The people in China play that. Mah Jongg, Chinese chess, Go and others , China Study and Publishing Society, Frankfurt am Main, no year, ISBN 3-88728-100-4

Web links

- The website of the German Xiangqi Association - Probably the largest German-speaking reservoir of information about games and gaming in Germany

- The rules of the game of Xiangqi - In German and with European pieces (PDF document; 303 kB)

- An introduction with Chinese and Europeanized pieces (English)

- Online course with interactive tasks

- Coffe Chinese Chess Online Java applet by Pham Hong Nguyen that can be played immediately on play.chessvariants.org (2003)

- Cole Xiangqi Online immediately playable program without Java, also for smartphones and tablets (2016)

Individual evidence

- ^ Charles F. Wilkes: A Manual of Chinese Chess , 1952.

- ↑ Dieter Ziehten: Xiangqi - Rules and Tactics of Chinese Chess , Hefei Huang Verlag

- ↑ HT Lau: Chinese Chess - An Introduction to China's Ancient Game of Strategy , Tuttle

- ↑ Rainer Schmidt: Introduction to the middle game tactics of Xingqi , special edition for the 1st World XQ Open

- ^ German Xiangqi Bund