South Gate, California and Oracle bone: Difference between pages

No edit summary |

for the Chinese characters found on oracle bones, see Oracle bone script |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{for|Chinese characters found on oracle bones|Oracle bone script}} |

|||

<!-- Infobox begins -->{{Infobox Settlement |

|||

{{Contains Chinese text}} |

|||

|official_name = City of South Gate |

|||

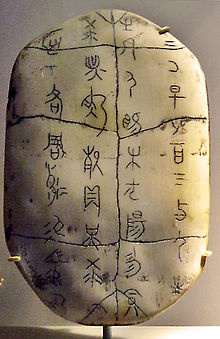

[[Image:OracleShell.JPG|thumbnail|right|Replica of an oracle bone -- turtle shell]] |

|||

|other_name = |

|||

|native_name = <!-- for cities whose native name is not in English --> |

|||

|nickname = |

|||

|motto = |

|||

|image_skyline = |

|||

|imagesize = |

|||

|image_caption = |

|||

|image_flag = |

|||

|flag_size = |

|||

|image_seal = South gate california seal.jpg |

|||

|seal_size = 221 |

|||

|image_shield = |

|||

|shield_size = |

|||

|image_blank_emblem = |

|||

|blank_emblem_size = |

|||

|image_map = LA County Incorporated Areas South Gate highlighted.svg |

|||

|mapsize = 250x200px |

|||

|map_caption = Location of South Gate in [[Los Angeles County, California|Los Angeles County]], [[California]] |

|||

|image_map1 = |

|||

|mapsize1 = |

|||

|map_caption1 = |

|||

|subdivision_type = [[List of countries|Country]] |

|||

|subdivision_name = [[United States]] |

|||

|subdivision_type1 = [[U.S. state|State]] |

|||

|subdivision_name1 = [[California]] |

|||

|subdivision_type2 = [[List of counties in California|County]] |

|||

|subdivision_name2 = [[Los Angeles County, California|Los Angeles]] |

|||

|subdivision_type3 = |

|||

|subdivision_name3 = |

|||

|subdivision_type4 = |

|||

|subdivision_name4 = |

|||

|government_type = |

|||

|leader_title = [[Mayor]] |

|||

|leader_name = Bill De Witt <ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.sogate.org/index.cfm/fuseaction/nav/navid/31/ | title = Meet the City Council | accessdate = 2007-08-02}}</ref> |

|||

|leader_title1 = <!-- for places with, say, both a mayor and a city manager --> |

|||

|leader_name1 = |

|||

|leader_title2 = |

|||

|leader_name2 = |

|||

|leader_title3 = |

|||

|leader_name3 = |

|||

|established_title = <!-- Settled --> |

|||

|established_date = |

|||

|established_title2 = <!-- Incorporated (town) --> |

|||

|established_date2 = |

|||

|established_title3 = Incorporated (city) |

|||

|established_date3 = [[1923-01-20]] <ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.cacities.org/resource_files/20457.IncorpDateLO.doc | title = Incorporation Dates of California Cities | accessdate = 2007-01-18|format=DOC}}</ref> |

|||

|area_magnitude = |

|||

|area_total_km2 = 19.38 |

|||

|area_total_sq_mi = 7.48 |

|||

|area_land_km2 = 19.08 |

|||

|area_land_sq_mi = 7.37 |

|||

|area_water_km2 = 0.30 |

|||

|area_water_sq_mi = 0.12 |

|||

|area_water_percent = 1.57 |

|||

|area_urban_km2 = |

|||

|area_urban_sq_mi = |

|||

|area_metro_km2 = |

|||

|area_metro_sq_mi = |

|||

|population_as_of = 2005 |

|||

|population_note = |

|||

|population_footnotes = <ref>{{cite web | url = http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ACSSAFFFacts?_event=Search&geo_id=&_geoContext=&_street=&_county=&_cityTown=South%20Gate&_state=04000US06&_zip=&_lang=en&_sse=on&pctxt=fph&pgsl=010 | title = South Gate city, California - Fact Sheet - American FactFinder | accessdate = 2007-01-17}}</ref> |

|||

|settlement_type = [[City]] |

|||

|population_total = 103,547 |

|||

|population_density_km2 = 5052.0 |

|||

|population_density_sq_mi = 13084.6 |

|||

|population_metro = |

|||

|population_density_metro_km2 = |

|||

|population_density_metro_sq_mi = |

|||

|population_urban = |

|||

|population_density_urban_km2 = |

|||

|population_density_urban_sq_mi = |

|||

|timezone = [[Pacific Time Zone|PST]] |

|||

|utc_offset = -8 |

|||

|timezone_DST = PDT |

|||

|utc_offset_DST = -7 |

|||

|latd = 33 |latm = 56 |lats = 39 |latNS = N |

|||

|longd = 118 |longm = 11 |longs = 42 |longEW = W |

|||

|elevation_m = 35 |

|||

|elevation_ft = 115 |

|||

|postal_code_type = [[ZIP Code]] |

|||

|postal_code = 90280 <ref>{{cite web | url = http://zip4.usps.com/zip4/zcl_1_results.jsp?visited=1&pagenumber=0&state=ca&city=South%20Gate | title = USPS - ZIP Code Lookup - Find a ZIP+ 4 Code By City Results | accessdate = 2007-01-18}}</ref> |

|||

|area_code = [[Area code 323|323]] <ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.nanpa.com/nas/public/npa_city_query_step2.do?method=displayData&cityToNpaModel.stateAbbr=CA&cityToNpaModel.city=South%20Gate | title = Number Administration System - NPA and City/Town Search Results | accessdate = 2007-01-18}}</ref> |

|||

|website = [http://www.sogate.org] |

|||

|blank_name = [[Federal Information Processing Standard|FIPS code]] |

|||

|blank_info = 06-73080 |

|||

|blank1_name = [[Geographic Names Information System|GNIS]] feature ID |

|||

|blank1_info = 1652795 |

|||

|footnotes = |

|||

}} |

|||

<!-- Infobox ends --> |

|||

'''Oracle bones''' ([[Chinese character|Chinese]]: 甲骨; [[pinyin]]: jiǎgǔpiàn) are pieces of [[bone]] or [[animal shell|turtle shell]] that were heated and cracked during divination, chiefly during the late [[Shang Dynasty|Shāng]], and then typically<ref>Not all oracle bones were inscribed after divination. (Xu Yahui p.30)</ref> inscribed with a record of the divination, in what is known as [[oracle bone script]]. The oracle bones are the earliest known significant<ref>The oracle bones are not the earliest writing in China--a '''very''' few isolated mid to late Shang pottery, bone and bronze inscriptions may predate them. However, the oracle bones are considered the earliest significant body of writing, due to the length of the inscriptions, the vast amount of vocabulary (very roughly 4000 graphs), and the sheer quantity of pieces found -- at least 100,000 pieces (Qiu 2000, p.61; Keightley 1978, p.xiii) bearing millions (Qiu 2000, p.49) of characters, and around 5,000 different characters (Qiu 2000, p.49), forming a full working vocabulary (Qiu 2000, p.50 cites various statistical studies before concluding that “the number of Chinese characters in general use is around five to six thousand”). It should be noted that there are also inscribed or brush-written [[Neolithic signs in China]], but they do not generally occur in strings of signs resembling writing; rather, they generally occur singly, and whether or not these constitute writing or are ancestral to the Shang writing system is currently a matter of great academic controversy. They are also insignificant in number compared to the massive amounts of oracle bones found so far. See Qiú 2000, Boltz 2003, and Woon 1987.</ref> corpus of ancient [[Written Chinese|Chinese writing]], and contain important historical information such as the complete royal genealogy of the Shāng dynasty<ref> Zhōu Hóngxiáng (周鴻翔) 1976 p.12 cites two such scapulae, citing his own “商殷帝王本紀” Shāng–Yīn dìwáng bĕnjì, pp. 18-21</ref>. These records confirmed the existence of the Shāng dynasty, which some scholars had recently begun to doubt. |

|||

'''South Gate''' is a city in [[Los Angeles County, California|Los Angeles County]], [[California]], [[United States]]. It is part of the [[Gateway Cities]] region of southeastern Los Angeles County. In 2005 the city had an estimated total population of 103,547.<ref>[http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ACSSAFFFacts?_event=Search&geo_id=01000US&_geoContext=01000US&_street=&_county=South+Gate&_cityTown=South+Gate&_state=04000US06&_zip=&_lang=en&_sse=on&ActiveGeoDiv=geoSelect&_useEV=&pctxt=fph&pgsl=010&_submenuId=factsheet_1&ds_name=ACS_2005_SAFF&_ci_nbr=null&qr_name=null®=null%3Anull&_keyword=&_industry= U.S. Census 2005 estimate]</ref> The "City of South Gate" was incorporated on [[20 January]] [[1923]] by the Los Angeles County [[Board of Supervisors]]<ref>http://www.cityofsouthgate.org/southgategardens.htm</ref>. |

|||

==Dating== |

|||

In 1990, South Gate was one of ten U.S. communities to receive the [[All-America City Award]] from the [[National Civic League]].<ref>[http://www.ncl.org/aac/past_winners/past_winners.html All-America City: Past Winners<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

The vast majority of the inscribed oracle bones date to the last 230 or so years of the Shāng dynasty; oracle bones have been reliably dated to the fourth and subsequent reigns of the kings who ruled at at [[Yin|Yīn]] (modern [[Anyang|Ānyáng]])—from king Wǔ Dīng (武丁) to Dì Xīn (帝辛).<ref> Keightley 1978, p.xiii; p.139</ref> However, the dating of these bones varies from ca. the 14th -11th centuries BCE <ref>裘錫圭 Qiú Xīguī (1993; 2000) Chinese Writing, p.29</ref><ref>Xu Yahui p.4</ref> to ca. 1200-1050 BCE<ref>Keightley 1978 p.xiii; see also pp.171-176</ref> because the end date of the Shāng dynasty is not a matter of consensus. The largest number date to the reign of king Wǔ Dīng<ref>55% of all fragments are Period I; Period I covers kings Pán Gēng (盤庚), Xiǎo Xīn (小辛), Xiǎo Yǐ (小乙) and Wǔ Dīng. However, few or perhaps none can be reliably assigned to pre-Wǔ Dīng reigns. Therefore about 55% of all oracle bone fragments found belong to the King Wǔ Dīng reign period. It is assumed that earlier oracle bones from [[Anyang|Ānyáng]] exist but have not been found yet. (Keightley 1978, p.139, 140 & 203)</ref> . Very few oracle bones date to the beginning of the subsequent [[Zhou Dynasty|Zhōu Dynasty]], as divination using [[milfoil]] (yarrow) became more common at that time. |

|||

==Discovery== |

|||

The city government has been criticized in 2002 for its corruption and one-sided votes. The city is on a progress calendar after governmental reform and improved accountability. Many new projects are under way as the city paves the way for the Gateway Communities. |

|||

[[Image:Orakelknochen.JPG|thumb|right|200px|A Shang Dynasty oracle bone from the [[Shanghai Museum]]]] |

|||

The Shāng-dynasty oracle bones are thought to have been unearthed periodically<ref>Qiu 2000, p.60</ref> by local farmers, ''perhaps'' starting as early as the [[Han dynasty|Hàn dynasty]],<ref> Zhōu Hóngxiáng (周鴻翔) 1976 p.1, citing Wei Juxian 1939, “Qín-Hàn shi fāxiàn jiǎgǔwén shuō”, in Shuōwén Yuè Kān, vol. 1, no.4; and He Tianxing 1940, "Jiǎgǔwén yi xianyu gǔdài shuō”, in Xueshu (Shànghǎi), no. 1</ref> and certainly by 19th century China, when they were sold as ''dragon bones'' (lóng gǔ 龍骨) in the [[Chinese herbology|traditional Chinese medicine]] markets, used either whole or crushed for the healing of various ailments.<ref>Fairbank, 2006, p. 33.</ref> The turtle shell fragments were prescribed for malaria<ref>Xu Yahui p.4-5 cites The Compendium of Materia Medica and includes a photo of the relevant page and entry.</ref>, while the other animal bones were used in powdered form to treat knife wounds<ref>Xu Yahui p.4</ref>. They were first recognized as bearing ancient Chinese writing by a scholar and high-ranking Qing dynasty official<ref>Xu Yahui p.4</ref>, Wáng Yìróng (王懿榮; 1845-1900) in 1899. A legendary<ref>Xu Yahui p.4</ref> tale states that Wang was sick with [[malaria]], and his scholar friend Liú È (刘鶚; 1857-1909) was visiting him and helped examine his medicine. They discovered, before it was ground into powder, that it bore strange glyphs, which they, having studied the ancient [[Bronzeware script|bronze inscriptions]], recognized as ancient writing. As Xǔ Yǎhuì (許雅惠 2002, p.4) states: |

|||

:''"No one can know how many oracle bones, prior to 1899, were ground up by traditional Chinese pharmacies and disappeared into peoples’ stomachs."'' |

|||

==Geography== |

|||

South Gate is located at {{coor dms|33|56|39|N|118|11|42|W|city}} (33.944264, -118.194903){{GR|1}}. |

|||

It is not known how Wang and Liu ''actually'' came across these “dragon bones”, but Wang is credited with being the first<ref>Xu Yahui p.4</ref> to recognize their significance, and his friend Liu was the first to publish a book on oracle bones<ref>Xu Yahui p.16</ref>. Word spread among collectors of antiquities, and the market for oracle bones exploded. Although scholars tried to find their source, antique dealers falsely claimed that the bones came from Tāngyīn (湯陰) <ref>Xu Yahui p.4</ref> in Hénán. Decades of uncontrolled digs<ref>Xu Yahui p.6 cites eight waves of illegal digs over three decades, with tens of thousands of pieces taken.</ref> followed to fuel the antiques trade, and many of these pieces eventually entered collections in Europe, the US, Canada and Japan<ref>Zhou 1976, p.1</ref>. The first Western collector was the American Rev. Frank H. Chalfant<ref>Rev. Chalfant acquired 803 oracle bone pieces between 1903 and 1908, and hand-traced over 2500 pieces including these. Zhōu 1976, p.1-2.</ref>, while Presbyterian minister James Mellon Menzies (明义士) (1885-1957) of Canada bought the largest amount<ref>Xu Yahui p.6</ref>. The Chinese still acknowledge the pioneering contribution of Menzies as "the foremost western scholar of Yin-Shang culture and oracle bone inscriptions." His former residence in Anyang was declared in 2004 a "Protected Treasure" and the James Mellon Menzies Memorial Museum for Oracle Bone Studies was established<ref>Wang Haiping (2006). "Menzies and Yin-Shang Culture Scholarship – An Unbreakable Bond." Anyang Ribao (Anyang Daily), August 12, 2006, p.1</ref><ref> See Linfu Dong (2005). Cross Culture snd Faith: the Life and Work of James Mellon Menzies. Toronto: University of Toronto Press</ref><ref> Geoff York (2008). "The unsung Canadian some knew as 'Old Bones' James Mellon Menzies, a man of God whose faith inspired him to unearth clues about the Middle Kingdom." Globe and Mail, January 18,2008, p. F4-5</ref> |

|||

According to the [[United States Census Bureau]], the city has a total [[area]] of 19.4 km² (7.5 [[square mile|mi²]]). 19.1 km² (7.4 mi²) of it is land and 0.3 km² (0.1 mi²) of it is [[water]]. The total area is 1.60% water. |

|||

==Official excavations== |

|||

The [[Los Angeles River]] runs through the eastern part of South Gate. |

|||

By the time of the establishment of the Institute of History and Philology headed by [[Fu Sinian|Fù Sīnián]] at the [[Academia Sinica]] in 1928, the source of the oracle bones had been traced back to modern Xiǎotún (小屯) village at [[Anyang|Ānyáng]] in [[Henan|Hénán]] Province. Official archaeological excavations in 1928-1937 led by Lĭ Jì (李濟; 1896-1979), the father of Chinese archaeology<ref>Xu Yahui, p.9</ref>, discovered 20,000 oracle bone pieces, which now form the bulk of the Academia Sinica's collection in [[Taiwan]] and constitute about 1/5 of the total discovered<ref>over 100,000 pieces have been found in all (Qiu 2000, p.61; Keightley 1978, p.xiii)</ref> . The inscriptions on the oracle bones, once deciphered, turned out to be the records of the divinations performed for or by the royal household. These, together with royal-sized tombs<ref>Eleven royal-sized tombs were found --Xu Yahui p.10; note that this exactly matches the number of kings who should have been buried at Yīn (the 12th king died in the Zhou conquest and would not have received a royal burial).</ref>, proved beyond a doubt for the first time the existence of the Shāng Dynasty, which had recently been doubted, and the location of its last capital, Yīn. Today, Xiǎotún at Ānyáng is thus also known as the Ruins of Yīn, or [[Yinxu|Yīnxū (殷墟)]]. |

|||

== |

==Materials== |

||

[[Image:CMOC Treasures of Ancient China exhibit - oracle bone inscription.jpg|thumb|In this [[Shang Dynasty]] oracle bone (which is incomplete), a diviner asks the Shang king if there would be misfortune over the next ten days; the king replied that he had consulted the ancestor ''Xiaojia'' in a worship ceremony.]] |

|||

Elected officials (as of August 2006): |

|||

The oracle bones are mostly [[tortoise]] [[plastron]]s (ventral or belly shells, probably female<ref>Keightley 1978, p.9 – the female shells are smoother, flatter and of more uniform thickness, facilitating pyromantic use.</ref>) and [[Cattle#Oxen|ox]] [[scapula]]e (shoulder blades), although some are the [[carapace]] (dorsal or back shells) of tortoises, and a few are ox rib bones<ref>According to Zhōu 1976 p.7, only four rib bones have been found.</ref>, scapulae of sheep, boars, horses and deer, and some other animal bones<ref>such as ox [[humerus]] or [[Talus bone|astragalus]] (ankle bone); see Zhōu 1976, p.1</ref>. The skulls of deer, ox skulls and human skulls<ref>Xu Yahui p.34 shows a large, clear photograph of a piece of inscribed human skull in the collection of the Institute of History and Philology at the Academia Sinica, Taiwan, presumably belonging to an enemy of the Shang.</ref> have also been found with inscriptions on them, although these are very rare, and appear to have been inscribed for record-keeping or practice rather than for actual divination<ref>Keightley 1978, p.7; note that there appears to be some confusion in published reports between inscribed bones in general, and bones which have actually been heated and cracked for use in divination</ref>; in one case inscribed deer antlers are reported, but Keightley (1978) reports that they are fake<ref>Keightley 1978, p.7, note 21; Xu Yahui p.35 does show an inscribed deer skull, thought to have been killed by a Shang king during a hunt.</ref>. Neolithic diviners in China had long been heating the bones of deer, sheep, pigs and cattle for similar purposes; evidence for this in [[Liaoning|Liáoníng]] has been found dating to the late fourth millennium BCE<ref>Keightley 1978, p.3</ref>. However, over time, the use of ox bones increased, and use of tortoise shells does not appear until early Shāng culture. The earliest tortoise shells found which had been prepared for oracle bone use (i.e., with chiseled pits) date to the earliest Shāng stratum at [[Erligang culture|Èrlĭgāng]] ([[Zhengzhou|Zhèngzhoū]], [[Henan|Hénán]])<ref>Keightley 1978 p.8</ref>. By the end of the Èrlĭgāng the plastrons were numerous<ref>Keightley 1978, p.8</ref>, and at [[Anyang|Ānyáng]] scapulae and plastrons were used in roughly equal numbers<ref>Keightley 1978, p.10</ref>. Due to the use of these shells in addition to bones, early references to the oracle bone script often used the term 'shell and bone script', but since tortoise shells are actually a bony material, the more concise term "oracle bones" is applied to them as well. |

|||

*Mayor: Bill De Witt |

|||

*Vice Mayor: Gil Hurtado |

|||

*Council Member: Henry Gonzalez |

|||

*Council Member: Gregory Martinez |

|||

*Council Member: Maria Davila |

|||

*Treasurer: Rudy Navarro |

|||

*Clerk: Carmen Avalos |

|||

===Scandal and corruption=== |

|||

From 2001 to 2003 city treasurer [[Albert Robles]] accepted bribes and funneled money to friends and relatives via city contracts. He, along with three allies on the city council, formed a majority and had effective control of the five member city council. In 2002 Robles was arrested then acquitted of threatening two other politicians. The city paid for his legal bills, however, amounting to 10% of the city budget. The city council cut the pay of [[city clerk]] Carmen Avalos by 90% after she complained about corruption and election fraud in the city to the California State Secretary.<ref name = "McGrath"> |

|||

{{ cite news |

|||

| title = South Gate: Mexico Comes to California; How an all-American town became a barrio |

|||

| url = http://www.amconmag.com/05_19_03/feature.html |

|||

| format = html |

|||

| work = 19 May 2003 Issue |

|||

| publisher = [[The American Conservative]] |

|||

| date = 19 May 2003 |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-12-01 |

|||

}}zip |

|||

</ref> |

|||

The bones or shells were first sourced, and then prepared for use. Their sourcing is significant because some of them (especially many of the shells) are believed to have been presented as tribute to the Shāng, which is valuable information about diplomatic relations of the time. We know this because notations were often made on them recording their provenance (e.g. tribute of how many shells from where and on what date). For example, one notation records that “Què (雀) sent 250 (tortoise shells)”, identifying this as, perhaps, a statelet within the Shāng sphere of influence<ref>Keightley 1978, p.9; Xu Yahui p.22. Some cattle scapulae were also tribute (Xu Yahui p.24.)</ref>. These notations were generally made on the back of the shell's bridge (called bridge notations), the lower carapace, or the xiphiplastron (tail edge). Some shells may have been from locally raised tortoises, however.<ref>Keightley 1978, p.12 mentions reports of Xiǎotún villagers finding hundreds of shells of all sizes, implying live tending or breeding of the turtles onsite.</ref> Scapula notations were near the socket or a lower edge. Some of these notations were not carved after being written with a brush, proving (along with other evidence) the use of the writing brush in Shāng times. Scapulae are assumed to have generally come from the Shāng’s own livestock, perhaps those used in ritual sacrifice, although there are records of cattle sent as tribute as well, including some recorded via marginal notations<ref>Keightley 1978, p.11</ref>. |

|||

On [[28 January]] [[2003]] voters recalled Robles along with former Mayor [[Xochitl Ruvalcaba]], former Vice Mayor [[Raul Moriel]], and former city councilwoman [[Maria Benavides]].<ref> |

|||

{{ cite web |

|||

| title = County of Los Angeles Department of Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk JANUARY 28, 2003 - SPECIAL ELECTION Final Official Election Returns (Los Angeles County Only) |

|||

| url = http://rrcc.co.la.ca.us/elect/03010262/rr0262pa.html-ssi |

|||

| format = html |

|||

| publisher = County of Los Angeles Department of Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk |

|||

| date = 28 January 2003 |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-12-01 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref><ref name = "NBC"> |

|||

{{ cite news |

|||

| title = South Gate Voters Clean House; Ousted Robles Said He May Seek Office Again |

|||

| url = http://www.nbc4.tv/news/1942556/detail.html |

|||

| format = html |

|||

| publisher = [[KNBC]] Los Angeles |

|||

| date = 29 January 2003 |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-12-01 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

==Preparation and usage== |

|||

Robles was convicted of bribery and other charges in July 2005,<ref name = "Rosenzweig"> |

|||

The bones or shells were cleaned of meat, and then prepared by sawing, scraping, smoothing and even polishing to create convenient, flat surfaces.<ref>Xu Yahui p.24; Zhou 1976 p.12 notes that evidence of sawing is present on some oracle bones, and that the saws were likely of bronze, although none have ever been found.</ref><ref>For details of the preparations, see Keightley 1978, pp.13-14.</ref> The predominance of scapulae and later of plastrons is also thought to be related to their convenience as large, flat surfaces needing minimal preparation. There is also speculation that only female tortoise shells were used, as these are significantly less concave<ref>Keightley 1978, p.9</ref>. Pits or hollows were then drilled or chiseled partway through the bone or shell in orderly series. At least one such drill has been unearthed at [[Erligang culture|Èrlĭgāng]], exactly matching the pits in size and shape<ref>Keightley 1978 p.18</ref>. The shape of these pits evolved over time, and is an important indicator for dating the oracle bones within various sub-periods in the Shāng dynasty. The shape and depth also helped determine the nature of the crack which would appear. The number of pits per bone or shell varied widely. |

|||

{{ cite news |

|||

| author = Rosenzweig, David |

|||

| title = Ex-South Gate treasurer convicted in bribery case |

|||

| url = http://www.cityethics.org/southgate |

|||

| format = html |

|||

| work = 29 July 2005 Issue |

|||

| publisher = [[Los Angeles Times]] |

|||

| date = 29 July 2005 |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-12-01 |

|||

}}</ref> ordered to pay the city of South Gate $639,000 in restitution, and sentenced to 10 years in federal prison.<ref> |

|||

{{ cite news |

|||

| author = Becerra, Hector |

|||

| title = Robles sentenced to 10 years; The former South Gate treasurer, convicted of stealing millions from the city, is taken into custody. He insists his power was exaggerated. |

|||

| url = http://www.latimes.com/news/local/politics/cal/la-me-robles29nov29,1,2110069.story?coll=la-news-politics-california |

|||

| format = html |

|||

| work = 29 November 2006 Issue |

|||

| publisher = Los Angeles Times |

|||

| date = 29 November 2006 |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-12-02 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

==Divination== |

|||

In March 2006, Rudy Navarro, who was elected to replace Albert Robles as city treasurer, was caught making a false statement on his biography as posted on the city's official web site. He claimed that he earned a degree from [[San Diego State University]], when he actually had not completed all the requirements.<ref>{{ cite web |

|||

[[Image:OracleBone.JPG|thumbnail|right|Replica of an oracle bone -- ox scapula]] |

|||

| title = SOUTH GATE CITY TREASURER |

|||

Since divination (-mancy) was by heat or fire (pyro-) and most often on plastrons or scapulae, the terms [[pyromancy]], plastromancy<ref>According to Keightley 1978, p.5, citing Yang Junshi 1963, the term plastromancy was coined by Li Ji</ref> and scapulimancy are often used for this process. Divinations were typically carried out for the Shāng kings, in the presence of a diviner. A very few oracle bones were used in divination by other members of the royal family or nobles close to the king. By the latest periods, the Shāng kings took over the role of diviner personally.<ref>Qiu 2000, p.61.</ref> |

|||

| url = http://www.cityofsouthgate.org/Navarro.htm |

|||

| format = html |

|||

| publisher = City of South Gate |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-12-016 |

|||

| quote = One of three children, Rudy is proud of the fact that he is the first member of his family to earn a college degree. He chose to attend San Diego State University, where he majored in both Finance and Political Science, with a minor in International Conflict Resolution. |

|||

}}</ref><ref> |

|||

{{ cite web |

|||

| title = Treasurer Elected to Help Clean Up South Gate Admits Resume Fib |

|||

| url = http://www.vote29.com/blog/archives/archive_2006-m03.php |

|||

| format = html |

|||

| publisher = Cactus Thorns; Irreverent Barbs On Desert Politics |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-12-01 |

|||

| date = 20 March 2006 |

|||

| quote = Rudy Navarro, 26, admitted he did not graduate from San Diego State University as he had claimed on the resume that's posted on the city's Web site, the Los Angeles Times reported Monday. "I don't know what I was thinking. It was stupid," said Navarro, adding that until this week he hadn't even told his parents he had yet to finish college. "Maybe it was the pressure to make myself look better than the previous person. My intention was really to come out and help." |

|||

}}</ref><ref> |

|||

{{ cite news |

|||

| title = (Unknown article title) |

|||

| url = http://www.mercurynews.com/mld/mercurynews/news/local/states/california/northern_california/14142032.htm |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

During a divination session, the shell or bone was anointed with blood <ref>Xu Yahui p.28, citing the [[Rites of Zhou|Rites of Zhōu]]</ref>, and in an inscription section called the 'preface', the date was recorded using the [[sexagenary cycle| Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches]], and the diviner name was noted. Next, the topic of divination (called the 'charge') was posed<ref>There is scholarly debate about whether the topic was posed as a question or not; Keightley prefers the term 'charge', since grammatical questions were often not involved</ref>, such as whether a particular ancestor was causing a king's toothache. The divination charges were often directed at ancestors, whom the ancient Chinese revered and worshiped, as well as natural powers and Dì (帝), the highest god in the Shāng society. A wide variety of topics were asked, essentially anything of concern to the royal house of Shāng, from illness, birth and death, to weather, warfare, agriculture, tribute and so on. One of the most common topics was whether performing rituals in a certain manner would be satisfactory.<ref>For a fuller overview of the topics of divination and what can be gleaned from them about the Shāng and their environment, see Keightley 2000.</ref> |

|||

South Gate's recent political history has been characterized by political observers and editors. An account of the South Gate corruption scandals can be found in journalist Sam Quinones' book ''Antonio's Gun and Delfino's Dream: True Tales of Mexican Migration''.<ref name = "Bebitch"> |

|||

{{ cite news |

|||

| author = Bebitch Jeffe, Sherry |

|||

| url = http://www.capitoljournal.com/news/features/_J.e.f.f.e./?7 |

|||

| title = Southgate |

|||

| publication = California Journal |

|||

| work = March 2004 Issue |

|||

| date = March 2003 |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-12-04 |

|||

| quote = Using a strategy reminiscent of old-style Mexican politics, the besieged incumbents began offering their constituents "freebies," including one-month's free trash service, a plan for free medical care out of a new health clinic, and raffles which awarded a new television set to one newly registered voter and a free, new house, offered by the city, to one lucky non-homeowner. |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref><ref name ="Marosi"> |

|||

{{ cite news |

|||

| author = Marosi, Richard |

|||

| url = http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/latimes/access/280534801.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&type=current&date=Jan+25%2C+2003&author=Richard+Marosi&pub=Los+Angeles+Times&desc=THE+NATION |

|||

| title = The Freebies Pile Up as South Gate Goes to Polls ; Some residents say the city's largess before a recall vote resembles the graft they saw in Mexico |

|||

| publication = Los Angeles Times |

|||

| work = 25 Jan 2003 Issue |

|||

| date = 25 January 2003 |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-12-04 |

|||

| quote = Have Third World politics come to South Gate? As three council members and the treasurer face a closely watched recall election Tuesday, many residents say the answer is yes... If the recall targets prevail, residents and political observers say, South Gate-style politics could spread to other Latino- majority communities, since candidates like to lift pages from other successful politicians' playbooks. |

|||

}}</ref><ref name ="Anderson"> |

|||

{{ cite news |

|||

| author = Anderson, Jeffrey |

|||

| url = http://www.laweekly.com/general/features/the-town-the-law-forgot/15731/ |

|||

| title = The Town the Law Forgot |

|||

| publication = L.A. Weekly |

|||

| date = 2007-02-21 |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-02-28 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

An intense heat source<ref>The nature of this heat source is still a matter of debate</ref> was then inserted in a pit until it cracked. Due to the shape of the pit, the front side of the bone cracked in a rough 卜 shape. The character 卜 (pinyin: bǔ or pǔ; [[Old Chinese]]: *puk; "to divine") may be a [[pictogram]] of such a crack; the reading of the character may also be an [[onomatopoeia]] for the cracking. A number of cracks were typically made in one session, sometimes on more than one bone, and these were typically numbered. The diviner in charge of the ceremony read the cracks to learn the answer to the divination. How exactly the cracks were interpreted is not known. The topic of divination was raised multiple times, and often in different ways, such as in the negative, or by changing the date being divined about. One oracle bone might be used for one session, or for many<ref>Most full (non-fragmentary) oracle bones bear multiple inscriptions; the longest of which are around 90 characters long: Qiu 2000, p.62</ref>, and one session could be recorded on a number of bones. The divined answer was sometimes then marked either "auspicious" or "inauspicious," and the king occasionally<ref>Xu Yahui p.30</ref> added a “prognostication”, his reading on the nature of the omen. On very rare<ref>Xu Yahui p.30</ref> occasions, the actual outcome was later added to the bone in what is known as a “verification”. A complete record of all the above elements is rare; most bones contain just the date, diviner and topic of divination,<ref>Xu Yahui p.30</ref> and many remained uninscribed after the divination<ref>Qiu 2000, p.62</ref>. |

|||

===Finances=== |

|||

South Gate was $150 million in debt in 2005.<ref name = "Rosenzweig" /> |

|||

This record is thought to have been brush-written on the oracle bones or accompanying documents, later to be carved in a workshop. As evidence of this, a few of the oracle bones found still bear their brush-written records<ref>Qiu 2000, p.60 mentions that some were written with a brush and either ink or cinnabar, but not carved</ref>, without carving, while some have been found partially carved. After use, the shells and bones which had seen ritual use<ref>Those which were for practice or records where buried in common rubbish pits (Xu Yahui p.32)</ref> were buried in separate pits (some for shells only; others for scapulae only), in groups of up to hundreds or even thousands (one pit unearthed in 1936 contained over 17,000 pieces along with a human skeleton)<ref>Xu Yahui p.32</ref>. |

|||

On [[June 5]], [[2007]], the city reported that it is facing a severe financial crisis [http://www.sogate.org/news/index.cfm/fuseaction/story/ID/26/]. |

|||

==Mythical origins of pyromancy== |

|||

==Economy== |

|||

A mythical account published in the [[Ming dynasty|Míng dynasty]] credits the mythical [[Fu Xi|Fú Xī]] with the invention of plastromancy, while a [[Song dynasty|Sòng dynasty]] account tells of tribute of a divine tortoise shell from what is now [[Vietnam]], sent to the court of the mythical emperor [[Yao (ruler)|Yáo]]<ref>Keightley 1978, p.8, n.26</ref>. |

|||

==Archaeological evidence of pre-Anyang pyromancy== |

|||

South Gate's commercial activity is concentrated in the following zones: |

|||

While the use of bones in divination has been practiced almost globally, such divination involving fire or heat has generally been found in Asia and the Asian-derived North American cultures<ref>Keightley 1978 p.3, p.4, and p.4 n.11 & 12.</ref>. The use of heat to crack scapulae (pyro-scapulimancy) originated in ancient China, the earliest<ref>Keightley 1978 p.3</ref> evidence of which extends back to the 4th millennium BCE, with archaeological finds from [[Liaoning|Liáoníng]], but these were not inscribed. In Neolithic China at a variety of sites, the scapulae of cattle, sheep, pigs and deer used in pyromancy have been found<ref>Keightley 1978, p.3; p.6, n.16</ref>, and the practice appears to have become quite common by the end of the third millennium BCE. Scapulae were unearthed along with smaller numbers of pitless plastrons in the Nánguānwài (南關外) stage at [[Zhengzhou|Zhèngzhoū]], [[Henan|Hénán]]; scapulae as well as smaller numbers of plastrons with chiseled pits were also discovered in the Lower and Upper [[Erligang|Èrlĭgāng]] stages<ref>Keightley 1978, p.8, note 25, citing KKHP 1973.1, pp.70, 79, 88, 91, plates 3.1, 4.2, 13.8</ref>. |

|||

Significant use of ''tortoise plastrons'' does not appear until the Shāng culture sites.<ref>Keightley p.8</ref> Ox scapulae and plastrons, both prepared for divination, were found at the Shāng culture sites of Táixīcūn (台西村) in [[Hebei|Hébĕi]], and Qiūwān (丘灣) in [[Jiangsu|Jiāngsū]]<ref>Keightley 1978, p.8, note 25 cites KK 1973.2 p.74</ref>. One or more pitted scapulae were found at Lùsìcūn (鹿寺村) in [[Henan|Hénán]], while unpitted scapulae have been found at [[Erlitou|Èrlĭtóu]] in [[Henan|Hénán]], Cíxiàn (磁縣) in [[Hebei|Hébĕi]], Níngchéng (寧城) in [[Liaoning|Liáoníng]], and Qíjiā (齊家) in [[Gansu|Gānsù]] <ref>Keightley 1978 p.6, n.16</ref>. Plastrons do not become more numerous than scapulae until the Rénmín (人民) Park phase<ref>Keightley 1978, p.8, note 25 cites Zhèngzhoū Èrlĭgāng, p.38</ref>. |

|||

*Tweedy Mile (from Long Beach Boulevard to Atlantic Avenue) |

|||

*[[Firestone Boulevard]] (from Alameda Street to Garfield Avenue) |

|||

*Garfield Avenue (at Firestone Boulevard; at Imperial Highway; and from McKinley Avenue to Century Boulevard) |

|||

As for pyromantic shells or bones ''with inscriptions'', the earliest date back to the site of [[Erligang culture|Èrlĭgāng]] in [[Zhengzhou|Zhèngzhoū]], [[Henan|Hénán]], where burned scapula of oxen, sheep and pigs were found, and one bone fragment from a pre-Shāng layer was inscribed with a graph (ㄓ) corresponding to Shāng [[oracle bone script]]. Another piece found at the site bears ten or more characters which are similar in form to the Shāng script but different in their pattern of use, and it is not clear what layer the piece came from<ref>Qiu Xigui 2000 p. 41cites Kexue Press 1959:38, also Fig. 30</ref>. |

|||

==Demographics== |

|||

As of the [[census]]{{GR|2}} of 2000, there are 96,375 people, 23,213 households, and 20,056 families residing in the city. The [[population density]] is 5,048.9/km² (13,084.6/mi²). There are 24,269 housing units at an average density of 1,271.4/km² (3,294.9/mi²). The racial makeup of the city is 0.78% [[White (U.S. Census)|White]], 0.19% [[African American (U.S. Census)|African American]], 9.93% [[Native American (U.S. Census)|Native American]], 0.83% [[Asian (U.S. Census)|Asian]], 0.12% [[Pacific Islander (U.S. Census)|Pacific Islander]], 94.69% of the population are [[Hispanic (U.S. Census)|Hispanic]] or [[Latino (U.S. Census)|Latino]] of any race. |

|||

==Post-Shāng oracle bones== |

|||

There are 23,213 households out of which 58.2% have children under the age of 18 living with them, 59.6% are [[Marriage|married couples]] living together, 18.4% have a female householder with no husband present, and 13.6% are non-families. 10.4% of all households are made up of individuals and 4.8% have someone living alone who is 65 years of age or older. The average household size is 4.15 and the average family size is 4.37. |

|||

After the Zhōu conquest, the Shāng practices of bronze casting, pyromancy and writing continued. Oracle bones found in the 1970s have been dated to the [[Zhou dynasty|Zhōu dynasty]], with some dating to the [[Spring and Autumn period]]. However, very few of those were inscribed; these very early inscribed Zhōu oracle bones are also known as the Zhōuyuán oracle bones. It is thought that other methods of divination supplanted pyromancy, such as numerological divination using [[Achillea millefolium|milfoil]] (yarrow) in connection with the hexagrams of the ''[[I Ching]]'', leading to the decline in inscribed oracle bones. However, evidence for the continued use of plastromancy exists for the [[Eastern Zhou|Eastern Zhōu]], [[Han dynasty|Hàn]], [[Tang Dynasty|Táng]]<ref>Keightley 1978 p.4 n.4</ref> and [[Qing Dynasty|Qīng]]<ref>Keightley 1978, p.9, n.30, citing Hu Xu 1782-1787, ch. 4, p.3b on use in Jiāngsū</ref> dynasty periods, and Keightley (1978, p.9) mentions use in [[Taiwan]] today<ref>Keightley cites Zhāng Guangyuan 1972</ref>. |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

In the city the population is spread out with 35.6% under the age of 18, 12.5% from 18 to 24, 31.6% from 25 to 44, 14.9% from 45 to 64, and 5.4% who are 65 years of age or older. The median age is 26 years. For every 100 females there are 98.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there are 95.5 males. |

|||

{{reflist|2}} |

|||

The median income for a household in the city is $35,695, and the median income for a family is $35,789. Males have a median income of $25,350 versus $19,978 for females. The [[per capita income]] for the city is $10,602. 19.2% of the population and 17.4% of families are below the [[poverty line]]. Out of the total population, 24.2% of those under the age of 18 and 12.0% of those 65 and older are living below the poverty line. |

|||

===Demographics history=== |

|||

The South Gate area was inhabited by the [[Gabrielino]]/[[Tongva]] Indians before development by Spanish ranchers. |

|||

South Gate developed during the 1920s and 1930s as an industrial city (primarily in "metal-bashing" industries) and its blue-collar community was predominantly non-Hispanic white.<ref>{{cite news |

|||

| author = McGrath, Roger D. |

|||

| title = South Gate: Mexico Comes to California; How an All-American Town Became a Barrio |

|||

| url = http://www.amconmag.com/05_19_03/feature.html |

|||

| format = html |

|||

| work = 19 May 2003 Issue |

|||

| publisher = The American Conservative |

|||

| date = 19 May 2003 |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-12-01 |

|||

| quote = The population was mostly blue collar: many of the new arrivals during the 1930s were Dust Bowl migrants who brought with them "hillbilly" music, Protestant fundamentalism, and rawboned toughness. |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> During the 1940s and 1950s, South Gate was one of the most fiercely segregationist cities in Southern California; gangs of white youths were known to prowl the streets looking for blacks who dared to cross over from neighboring [[Watts, Los Angeles, California|Watts]]. One of the most infamous clubs of the area at that time was the [[Spook Hunters]]. <ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.streetgangs.com/history/hist01.html |

|||

| title = Black Street Gangs in Los Angeles: A History (excerpts from Territoriality Among African American Street Gangs in Los Angeles) |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-12-01 |

|||

| author = Alonso, Alex |

|||

| format = html |

|||

| work = Territoriality Among African American Street Gangs in Los Angeles |

|||

| quote = In Huntington Park, Bell, and South Gate, towns that were predominately white, teenagers formed some of the early street clubs during the 1940s. One of the most infamous clubs of that time was the [[Spook Hunters]], a group of white teenagers that often attacked black youths. If blacks were seen outside of the black settlement area, which was roughly bounded by Slauson to the South, Alameda Avenue to the east, and Main[5] Street to the west, they were often attacked. The name of this club emphasized their racist attitude towards blacks, as “Spook” is a derogatory term used to identify blacks and “Hunters” highlighted their desire to attack blacks as their method of fighting integration and promoting residential segregation. Their animosity towards blacks was publicly known; the back of their club jackets displayed an animated black face with exaggerated facial features and a noose hanging around the neck. The Spook Hunters would often cross Alameda traveling west to violently attack black youths from the area. In Thrasher’s study of Chicago gangs, he observed a similar white gang in Chicago during the 1920s, the Dirty Dozens, who often attacked black youths with knives, blackjacks, and revolvers because of racial differences (Thrasher 1963:37). Raymond Wright was one of the founders of a black club called the Businessmen, a large East side club based at South Park between Slauson Avenue and Vernon Avenue. He stated that “you couldn’t pass Alameda, because those white boys in South Gate would set you on fire,”[6] and fear of attack among black youths was not, surprisingly, common. In 1941, white students at Fremont High School threatened blacks by burning them in effigy and displaying posters saying, “we want no niggers at this school” (Bunch 1990: 118). There were racial confrontations at Manual Arts High School on Vermont and 42nd Street, and at Adams High School during the 1940s (Davis 1990:293). In 1943, conflicts between blacks and whites occurred at 5th and San Pedro Streets, resulting in a riot on Central Avenue (Bunch 1990:118). white clubs in Inglewood, Gardena, and on the West side engaged in similar acts, but the Spook Hunters were the most violent of all white clubs in Los Angeles. |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

After the [[Watts Riots]] in 1965, many young non-Hispanic white families began to flee South Gate for other areas.<ref> |

|||

{{cite news |

|||

| author = McGrath, Roger D. |

|||

| title = South Gate: Mexico Comes to California; How an All-American Town Became a Barrio |

|||

| url = http://www.amconmag.com/05_19_03/feature.html |

|||

| format = html |

|||

| work = 19 May 2003 Issue |

|||

| publisher = The American Conservative |

|||

| date = 19 May 2003 |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-12-01 |

|||

| quote = In August 1965, the Watts riots erupted. Watts was virtually 100 percent black, and South Gate, immediately to the east of Watts, was nearly 100 percent white. |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Since the 1970s, South Gate has had a large [[Hispanic]] community, which became dominant in the 1990s as working-class [[Hispanics]] and immigrant Latin American families filled the vacuum left by [[white flight]]. |

|||

==Politics== |

|||

In the [[California State Legislature|state legislature]] South Gate is located in the 27th and 30th [[California State Senate|Senate]] Districts, represented by Democrats [[Alan Lowenthal]] and [[Ronald S. Calderon]] respectively, and in the 50th [[California State Assembly|Assembly]] District, represented by Democrat [[Hector De La Torre]]. Federally, South Gate is located in [[California's 39th congressional district]], which has a [[Cook Partisan Voting Index|Cook PVI]] of D +13<ref>{{cite web | title = Will Gerrymandered Districts Stem the Wave of Voter Unrest? | publisher = Campaign Legal Center Blog | url=http://www.clcblog.org/blog_item-85.html | accessdate = 2008-02-10}}</ref> and is represented by Democrat [[Linda Sánchez]]. |

|||

==Education== |

|||

===Primary and secondary schools=== |

|||

====Public schools==== |

|||

Most of South Gate is served by the [[Los Angeles Unified School District]] public school system. A small section of South Gate is served by the [[Paramount Unified School District]] and Downey Unified School District.<ref name = "hollydale elementary">{{cite web | url = http://www.greatschools.net/modperl/browse_school/ca/2764 | title = Hollydale Elementary School - South Gate, CA - school overview | accessdate = 2006-12-27}}</ref><ref> {{cite web | url = http://www.paramount.k12.ca.us/schools/hollydale.html | title = PUSD: Schools : Hollydale | accessdate = 2006-12-27}}</ref> |

|||

===== Los Angeles Unified School District ===== |

|||

======LAUSD primary schools====== |

|||

*[http://www.lausd.k12.ca.us/Bryson_EL Bryson Avenue Elementary School] (Opened 1931) |

|||

*Independence Elementary School (Opened 1997) |

|||

*[http://www.lausd.k12.ca.us/Liberty_EL/ Liberty Boulevard Elementary School] (Opened 1932) |

|||

*Madison Elementary School <!--South Gate New Elementary School #6--> (Opened 2005)<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.laschools.org/project-status/one-project?project_number=47.08402 | title = LAUSD Facilities Services Division: Project Details: South Gate New ES #6, 47.08402}}</ref> |

|||

*Montara Avenue Elementary School (Opened 1988) |

|||

*San Gabriel Avenue Elementary School (Opened 1920) |

|||

*[http://san-miguel.lausd.k12.ca.us/ San Miguel Avenue Elementary School] (Opened 1989, partially a math and science [[magnet school]]) |

|||

*[http://www.lausd.k12.ca.us/Stanford_EL/ Stanford Avenue Elementary School] (1-5, Opened 1924) |

|||

*Stanford New Primary Center (K, Opened 2004)<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.laschools.org/project-status/one-project?project_number=47.07402 | title = LAUSD Facilities Services Division: Project Details: Stanford New PC, 47.07402}}</ref> |

|||

*State Street Elementary School (Opened 1932) |

|||

*Tweedy Elementary School (Opened 2004)<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.laschools.org/project-status/one-project?project_number=55.98027 | title = LAUSD Facilities Services Division: Project Details: South Gate New ES #7, 55.98027}}</ref> |

|||

*[http://www.lausd.k12.ca.us/Victoria_EL Victoria Avenue Elementary School] (Opened 1925) |

|||

======LAUSD middle schools====== |

|||

*[http://www.lausd.k12.ca.us/South_Gate_MS/ South Gate Middle School] (Opened 1941) |

|||

*[[Southeast Middle School (South Gate, California)|South East Middle School]] (Opened 2004)<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.laschools.org/project-status/one-project?project_number=55.98028 | title = LAUSD Facilities Services Division: Project Details: Southeast Area New MS #3, 55.98028}}</ref> |

|||

======LAUSD high schools====== |

|||

*[[South Gate High School]] (Opened 1932) |

|||

*[[South East High School (South Gate, California)|South East High School]] (Opened 2005)<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.laschools.org/project-status/one-project?project_number=55.98034 | title = LAUSD Facilities Services Division: Project Details: Southeast Area New HS #2, 55.98034}}</ref> |

|||

======LAUSD middle and high schools====== |

|||

*International Studies Learning Center (opened in 2005) |

|||

===== Paramount Unified School District ===== |

|||

*[http://www.paramount.k12.ca.us/schools/hollydale.html Hollydale School] (K-8) |

|||

*[[Paramount High School]] |

|||

Part of South Gate is served by Downey Unified School District. |

|||

====Private schools==== |

|||

=====Private primary schools===== |

|||

*Lollypop Lane Preschool and Kindergarten |

|||

*Redeemer Lutheran School |

|||

*Saint Helen Elementary School |

|||

=====Private high schools===== |

|||

*Academia Betel |

|||

*Faith Christian Academy |

|||

===Continuation Schools=== |

|||

*Odyssey Continuation School |

|||

===Colleges and Universities=== |

|||

*Career College of America |

|||

*South Gate Satellite Campus, [[East Los Angeles College]] |

|||

==Future additions to South Gate== |

|||

* Atlantic Park Plaza |

|||

* Firestone Village and Shops |

|||

* Gateway Project |

|||

* Tierra Del Rey luxurious private town homes |

|||

==Trivia== |

|||

{{Trivia|date=June 2007}} |

|||

* The A.R. Maas Chemical Company began operating in South Gate in 1922. |

|||

*[[Firestone Tire and Rubber Company]] built its South Gate factory on a former bean field and produced its first tire there on [[15 June]] [[1928]].<ref name="autogenerated1">http://www.cityofsouthgate.org/thenewcity.htm</ref> |

|||

*In 1936 the General Motors plant went into production in South Gate with 1,000 employees.<ref name="autogenerated1" /> |

|||

*South Gate has 4 area codes : 323, 562, 310, and 424 (overlay to 310 area code).<ref>http://www.cpuc.ca.gov/Static/telco/reports/area+code+info/ac310pubmtgs/areacodechange-310npa_overlaymap.pdf</ref> |

|||

*A dramatic incident occurred at the last city council meeting after the 2003 recall election: The mayor, Xochitl Ruvalcaba, punched then 67 year old councilmember Henry Gonzalez as he reached for a ''speaker's card'' that she refused to hand-over for review; she later accused him of trying to fondle her [[breast]] during the public city council meeting.<ref name = "McGrath" /><ref> |

|||

{{ cite news |

|||

| author = York, Anthony |

|||

| title = Personal ties lead Dymally into Vernon elections fight |

|||

| url = http://www.capitolweekly.net/news/article.html?article_id=856 |

|||

| format = html |

|||

| work = 20 July 2006 Issue |

|||

| publisher = Capitol Weekly: A Newspaper of California Government and Politicsc |

|||

| date = 20 July 2006 |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-12-01 |

|||

}}</ref><ref> |

|||

{{ cite news |

|||

| title = Mayor Punches Councilman At Her Last Meeting; Audience Members: 'Arrest The Mayor' |

|||

| url = http://www.simpletoremember.com/what/mayorpunch.htm |

|||

| format = html |

|||

| publisher = [[Associated Press]] |

|||

| date = 4 February 2003 |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-12-01 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

* Was officially home to the [[16th World Science Fiction Convention]], "Solacon", in 1958. Solacon was physically in Los Angeles, but (by mayoral proclamation) technically in South Gate to fulfill their bid slogan of "South Gate in 58."<ref>[http://www.nesfa.org/data/LL/LongListNotes.html#1958 Notes on the Long List of Worldcons<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[South Los Angeles|South Central Los Angeles]] |

|||

* [[Albert Robles]] |

|||

* [[Seaborg Home (South Gate, California)|Seaborg Home]] |

|||

* [[South Gate High School]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

*Boltz, William G. (1994). The Origin and Early Development of the Chinese Writing System. American Oriental Series, vol. 78. American Oriental Society, New Haven, Connecticut, USA. ISBN 0-940490-18-8 |

|||

{{reflist|2}} |

|||

*Fairbank, John King and Merle Goldman (1992). ''China: A New History; Second Enlarged Edition'' (2006). Cambridge; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01828-1. |

|||

*Keightley, David N. (1978). ''Sources of Shang History: The Oracle-Bone Inscriptions of Bronze Age China''. University of California Press, Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-02969-0; Paperback 2nd edition (1985) ISBN 0-520-05455-5. |

|||

==External links== |

|||

*Keightley, David N. (2000). ''The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China (ca. 1200 – 1045 B.C.)''. China Research Monograph 53, Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 1-55729-070-9. |

|||

*[http://www.cityofsouthgate.org/ CityOfSouthGate.org] - South Gate's official Site |

|||

*Qiu Xigui (裘錫圭) (2000). ''Chinese Writing''. Translation of 文字学概要 by Gilbert L. Mattos and Jerry Norman. Early China Special Monograph Series No. 4. The Society for the Study of Early China and the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 1-55729-071-7. |

|||

*[http://www.southgatehs.org/ SouthGateHS.org] - South Gate High School's official website. |

|||

*Woon, Wee Lee 雲惟利 (1987). “Chinese Writing: Its Origin and Evolution” (in English; Chinese title漢字的原始和演變). Originally published by the Univ. of East Asia, Macau; now by Joint Publishing, Hong Kong. |

|||

*[http://www.lausd.k12.ca.us/South_East_HS/ SouthEastHS.com] - South East High School's official |

|||

*Xǔ Yǎhuì (許雅惠 Hsu Ya-huei) (2002). ''Ancient Chinese Writing, Oracle Bone Inscriptions from the Ruins of Yin''. Illustrated guide to the Special Exhibition of Oracle Bone Inscriptions from the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica. English translation by [[Mark Caltonhill]] and Jeff Moser. National Palace Museum, Taipei. Govt. Publ. No. 1009100250. |

|||

*[http://www.southgatechamber.org/ SouthGateChamber.org] - South Gate Chamber of Commerce official website. |

|||

* Zhōu Hóngxiáng (周鴻翔, wg Chou Hung-hsiang) (1976). “Oracle Bone Collections in the United States”. University of California Press, Berkeley – Los Angeles – London. ISBN 0-520-09534-0. |

|||

{{Mapit-US-cityscale|33.944264|-118.194903}} |

|||

*[http://www.samquinones.com/ www.samquinones.com] -- website of journalist Sam Quinones |

|||

<br />{{Time in religion and mythology}} |

|||

{{Cities of Los Angeles County, California}} |

|||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Archaeology of China]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Shang Dynasty]] |

||

[[Category:California political scandals]] |

|||

[[Category:California communities with Hispanic majority populations]] |

|||

[[da:Orakelben]] |

|||

[[ar:سووث غاتي، لوس أنجليس، كاليفورنيا]] |

|||

[[de:Orakelknochen]] |

|||

[[bg:Южен Гейт (Калифорния)]] |

|||

[[ |

[[es:Hueso oracular]] |

||

[[eo:Orakola osto]] |

|||

[[fr:South Gate (Californie)]] |

|||

[[fr:Écriture ossécaille]] |

|||

[[ht:South Gate, Kalifòni]] |

|||

[[nl: |

[[nl:Orakelbot]] |

||

[[no:Orakelben]] |

|||

[[pt:South Gate (Califórnia)]] |

|||

[[ru:Гадательные кости]] |

|||

[[vo:South Gate (California)]] |

|||

[[simple:Oracle bone]] |

|||

[[sv:Orakelbensskrift]] |

|||

Revision as of 04:36, 14 October 2008

Template:Contains Chinese text

Oracle bones (Chinese: 甲骨; pinyin: jiǎgǔpiàn) are pieces of bone or turtle shell that were heated and cracked during divination, chiefly during the late Shāng, and then typically[1] inscribed with a record of the divination, in what is known as oracle bone script. The oracle bones are the earliest known significant[2] corpus of ancient Chinese writing, and contain important historical information such as the complete royal genealogy of the Shāng dynasty[3]. These records confirmed the existence of the Shāng dynasty, which some scholars had recently begun to doubt.

Dating

The vast majority of the inscribed oracle bones date to the last 230 or so years of the Shāng dynasty; oracle bones have been reliably dated to the fourth and subsequent reigns of the kings who ruled at at Yīn (modern Ānyáng)—from king Wǔ Dīng (武丁) to Dì Xīn (帝辛).[4] However, the dating of these bones varies from ca. the 14th -11th centuries BCE [5][6] to ca. 1200-1050 BCE[7] because the end date of the Shāng dynasty is not a matter of consensus. The largest number date to the reign of king Wǔ Dīng[8] . Very few oracle bones date to the beginning of the subsequent Zhōu Dynasty, as divination using milfoil (yarrow) became more common at that time.

Discovery

The Shāng-dynasty oracle bones are thought to have been unearthed periodically[9] by local farmers, perhaps starting as early as the Hàn dynasty,[10] and certainly by 19th century China, when they were sold as dragon bones (lóng gǔ 龍骨) in the traditional Chinese medicine markets, used either whole or crushed for the healing of various ailments.[11] The turtle shell fragments were prescribed for malaria[12], while the other animal bones were used in powdered form to treat knife wounds[13]. They were first recognized as bearing ancient Chinese writing by a scholar and high-ranking Qing dynasty official[14], Wáng Yìróng (王懿榮; 1845-1900) in 1899. A legendary[15] tale states that Wang was sick with malaria, and his scholar friend Liú È (刘鶚; 1857-1909) was visiting him and helped examine his medicine. They discovered, before it was ground into powder, that it bore strange glyphs, which they, having studied the ancient bronze inscriptions, recognized as ancient writing. As Xǔ Yǎhuì (許雅惠 2002, p.4) states:

- "No one can know how many oracle bones, prior to 1899, were ground up by traditional Chinese pharmacies and disappeared into peoples’ stomachs."

It is not known how Wang and Liu actually came across these “dragon bones”, but Wang is credited with being the first[16] to recognize their significance, and his friend Liu was the first to publish a book on oracle bones[17]. Word spread among collectors of antiquities, and the market for oracle bones exploded. Although scholars tried to find their source, antique dealers falsely claimed that the bones came from Tāngyīn (湯陰) [18] in Hénán. Decades of uncontrolled digs[19] followed to fuel the antiques trade, and many of these pieces eventually entered collections in Europe, the US, Canada and Japan[20]. The first Western collector was the American Rev. Frank H. Chalfant[21], while Presbyterian minister James Mellon Menzies (明义士) (1885-1957) of Canada bought the largest amount[22]. The Chinese still acknowledge the pioneering contribution of Menzies as "the foremost western scholar of Yin-Shang culture and oracle bone inscriptions." His former residence in Anyang was declared in 2004 a "Protected Treasure" and the James Mellon Menzies Memorial Museum for Oracle Bone Studies was established[23][24][25]

Official excavations

By the time of the establishment of the Institute of History and Philology headed by Fù Sīnián at the Academia Sinica in 1928, the source of the oracle bones had been traced back to modern Xiǎotún (小屯) village at Ānyáng in Hénán Province. Official archaeological excavations in 1928-1937 led by Lĭ Jì (李濟; 1896-1979), the father of Chinese archaeology[26], discovered 20,000 oracle bone pieces, which now form the bulk of the Academia Sinica's collection in Taiwan and constitute about 1/5 of the total discovered[27] . The inscriptions on the oracle bones, once deciphered, turned out to be the records of the divinations performed for or by the royal household. These, together with royal-sized tombs[28], proved beyond a doubt for the first time the existence of the Shāng Dynasty, which had recently been doubted, and the location of its last capital, Yīn. Today, Xiǎotún at Ānyáng is thus also known as the Ruins of Yīn, or Yīnxū (殷墟).

Materials

The oracle bones are mostly tortoise plastrons (ventral or belly shells, probably female[29]) and ox scapulae (shoulder blades), although some are the carapace (dorsal or back shells) of tortoises, and a few are ox rib bones[30], scapulae of sheep, boars, horses and deer, and some other animal bones[31]. The skulls of deer, ox skulls and human skulls[32] have also been found with inscriptions on them, although these are very rare, and appear to have been inscribed for record-keeping or practice rather than for actual divination[33]; in one case inscribed deer antlers are reported, but Keightley (1978) reports that they are fake[34]. Neolithic diviners in China had long been heating the bones of deer, sheep, pigs and cattle for similar purposes; evidence for this in Liáoníng has been found dating to the late fourth millennium BCE[35]. However, over time, the use of ox bones increased, and use of tortoise shells does not appear until early Shāng culture. The earliest tortoise shells found which had been prepared for oracle bone use (i.e., with chiseled pits) date to the earliest Shāng stratum at Èrlĭgāng (Zhèngzhoū, Hénán)[36]. By the end of the Èrlĭgāng the plastrons were numerous[37], and at Ānyáng scapulae and plastrons were used in roughly equal numbers[38]. Due to the use of these shells in addition to bones, early references to the oracle bone script often used the term 'shell and bone script', but since tortoise shells are actually a bony material, the more concise term "oracle bones" is applied to them as well.

The bones or shells were first sourced, and then prepared for use. Their sourcing is significant because some of them (especially many of the shells) are believed to have been presented as tribute to the Shāng, which is valuable information about diplomatic relations of the time. We know this because notations were often made on them recording their provenance (e.g. tribute of how many shells from where and on what date). For example, one notation records that “Què (雀) sent 250 (tortoise shells)”, identifying this as, perhaps, a statelet within the Shāng sphere of influence[39]. These notations were generally made on the back of the shell's bridge (called bridge notations), the lower carapace, or the xiphiplastron (tail edge). Some shells may have been from locally raised tortoises, however.[40] Scapula notations were near the socket or a lower edge. Some of these notations were not carved after being written with a brush, proving (along with other evidence) the use of the writing brush in Shāng times. Scapulae are assumed to have generally come from the Shāng’s own livestock, perhaps those used in ritual sacrifice, although there are records of cattle sent as tribute as well, including some recorded via marginal notations[41].

Preparation and usage

The bones or shells were cleaned of meat, and then prepared by sawing, scraping, smoothing and even polishing to create convenient, flat surfaces.[42][43] The predominance of scapulae and later of plastrons is also thought to be related to their convenience as large, flat surfaces needing minimal preparation. There is also speculation that only female tortoise shells were used, as these are significantly less concave[44]. Pits or hollows were then drilled or chiseled partway through the bone or shell in orderly series. At least one such drill has been unearthed at Èrlĭgāng, exactly matching the pits in size and shape[45]. The shape of these pits evolved over time, and is an important indicator for dating the oracle bones within various sub-periods in the Shāng dynasty. The shape and depth also helped determine the nature of the crack which would appear. The number of pits per bone or shell varied widely.

Divination

Since divination (-mancy) was by heat or fire (pyro-) and most often on plastrons or scapulae, the terms pyromancy, plastromancy[46] and scapulimancy are often used for this process. Divinations were typically carried out for the Shāng kings, in the presence of a diviner. A very few oracle bones were used in divination by other members of the royal family or nobles close to the king. By the latest periods, the Shāng kings took over the role of diviner personally.[47]

During a divination session, the shell or bone was anointed with blood [48], and in an inscription section called the 'preface', the date was recorded using the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches, and the diviner name was noted. Next, the topic of divination (called the 'charge') was posed[49], such as whether a particular ancestor was causing a king's toothache. The divination charges were often directed at ancestors, whom the ancient Chinese revered and worshiped, as well as natural powers and Dì (帝), the highest god in the Shāng society. A wide variety of topics were asked, essentially anything of concern to the royal house of Shāng, from illness, birth and death, to weather, warfare, agriculture, tribute and so on. One of the most common topics was whether performing rituals in a certain manner would be satisfactory.[50]

An intense heat source[51] was then inserted in a pit until it cracked. Due to the shape of the pit, the front side of the bone cracked in a rough 卜 shape. The character 卜 (pinyin: bǔ or pǔ; Old Chinese: *puk; "to divine") may be a pictogram of such a crack; the reading of the character may also be an onomatopoeia for the cracking. A number of cracks were typically made in one session, sometimes on more than one bone, and these were typically numbered. The diviner in charge of the ceremony read the cracks to learn the answer to the divination. How exactly the cracks were interpreted is not known. The topic of divination was raised multiple times, and often in different ways, such as in the negative, or by changing the date being divined about. One oracle bone might be used for one session, or for many[52], and one session could be recorded on a number of bones. The divined answer was sometimes then marked either "auspicious" or "inauspicious," and the king occasionally[53] added a “prognostication”, his reading on the nature of the omen. On very rare[54] occasions, the actual outcome was later added to the bone in what is known as a “verification”. A complete record of all the above elements is rare; most bones contain just the date, diviner and topic of divination,[55] and many remained uninscribed after the divination[56].

This record is thought to have been brush-written on the oracle bones or accompanying documents, later to be carved in a workshop. As evidence of this, a few of the oracle bones found still bear their brush-written records[57], without carving, while some have been found partially carved. After use, the shells and bones which had seen ritual use[58] were buried in separate pits (some for shells only; others for scapulae only), in groups of up to hundreds or even thousands (one pit unearthed in 1936 contained over 17,000 pieces along with a human skeleton)[59].

Mythical origins of pyromancy

A mythical account published in the Míng dynasty credits the mythical Fú Xī with the invention of plastromancy, while a Sòng dynasty account tells of tribute of a divine tortoise shell from what is now Vietnam, sent to the court of the mythical emperor Yáo[60].

Archaeological evidence of pre-Anyang pyromancy

While the use of bones in divination has been practiced almost globally, such divination involving fire or heat has generally been found in Asia and the Asian-derived North American cultures[61]. The use of heat to crack scapulae (pyro-scapulimancy) originated in ancient China, the earliest[62] evidence of which extends back to the 4th millennium BCE, with archaeological finds from Liáoníng, but these were not inscribed. In Neolithic China at a variety of sites, the scapulae of cattle, sheep, pigs and deer used in pyromancy have been found[63], and the practice appears to have become quite common by the end of the third millennium BCE. Scapulae were unearthed along with smaller numbers of pitless plastrons in the Nánguānwài (南關外) stage at Zhèngzhoū, Hénán; scapulae as well as smaller numbers of plastrons with chiseled pits were also discovered in the Lower and Upper Èrlĭgāng stages[64].

Significant use of tortoise plastrons does not appear until the Shāng culture sites.[65] Ox scapulae and plastrons, both prepared for divination, were found at the Shāng culture sites of Táixīcūn (台西村) in Hébĕi, and Qiūwān (丘灣) in Jiāngsū[66]. One or more pitted scapulae were found at Lùsìcūn (鹿寺村) in Hénán, while unpitted scapulae have been found at Èrlĭtóu in Hénán, Cíxiàn (磁縣) in Hébĕi, Níngchéng (寧城) in Liáoníng, and Qíjiā (齊家) in Gānsù [67]. Plastrons do not become more numerous than scapulae until the Rénmín (人民) Park phase[68].

As for pyromantic shells or bones with inscriptions, the earliest date back to the site of Èrlĭgāng in Zhèngzhoū, Hénán, where burned scapula of oxen, sheep and pigs were found, and one bone fragment from a pre-Shāng layer was inscribed with a graph (ㄓ) corresponding to Shāng oracle bone script. Another piece found at the site bears ten or more characters which are similar in form to the Shāng script but different in their pattern of use, and it is not clear what layer the piece came from[69].

Post-Shāng oracle bones

After the Zhōu conquest, the Shāng practices of bronze casting, pyromancy and writing continued. Oracle bones found in the 1970s have been dated to the Zhōu dynasty, with some dating to the Spring and Autumn period. However, very few of those were inscribed; these very early inscribed Zhōu oracle bones are also known as the Zhōuyuán oracle bones. It is thought that other methods of divination supplanted pyromancy, such as numerological divination using milfoil (yarrow) in connection with the hexagrams of the I Ching, leading to the decline in inscribed oracle bones. However, evidence for the continued use of plastromancy exists for the Eastern Zhōu, Hàn, Táng[70] and Qīng[71] dynasty periods, and Keightley (1978, p.9) mentions use in Taiwan today[72].

Notes

- ^ Not all oracle bones were inscribed after divination. (Xu Yahui p.30)

- ^ The oracle bones are not the earliest writing in China--a very few isolated mid to late Shang pottery, bone and bronze inscriptions may predate them. However, the oracle bones are considered the earliest significant body of writing, due to the length of the inscriptions, the vast amount of vocabulary (very roughly 4000 graphs), and the sheer quantity of pieces found -- at least 100,000 pieces (Qiu 2000, p.61; Keightley 1978, p.xiii) bearing millions (Qiu 2000, p.49) of characters, and around 5,000 different characters (Qiu 2000, p.49), forming a full working vocabulary (Qiu 2000, p.50 cites various statistical studies before concluding that “the number of Chinese characters in general use is around five to six thousand”). It should be noted that there are also inscribed or brush-written Neolithic signs in China, but they do not generally occur in strings of signs resembling writing; rather, they generally occur singly, and whether or not these constitute writing or are ancestral to the Shang writing system is currently a matter of great academic controversy. They are also insignificant in number compared to the massive amounts of oracle bones found so far. See Qiú 2000, Boltz 2003, and Woon 1987.

- ^ Zhōu Hóngxiáng (周鴻翔) 1976 p.12 cites two such scapulae, citing his own “商殷帝王本紀” Shāng–Yīn dìwáng bĕnjì, pp. 18-21

- ^ Keightley 1978, p.xiii; p.139

- ^ 裘錫圭 Qiú Xīguī (1993; 2000) Chinese Writing, p.29

- ^ Xu Yahui p.4

- ^ Keightley 1978 p.xiii; see also pp.171-176

- ^ 55% of all fragments are Period I; Period I covers kings Pán Gēng (盤庚), Xiǎo Xīn (小辛), Xiǎo Yǐ (小乙) and Wǔ Dīng. However, few or perhaps none can be reliably assigned to pre-Wǔ Dīng reigns. Therefore about 55% of all oracle bone fragments found belong to the King Wǔ Dīng reign period. It is assumed that earlier oracle bones from Ānyáng exist but have not been found yet. (Keightley 1978, p.139, 140 & 203)

- ^ Qiu 2000, p.60

- ^ Zhōu Hóngxiáng (周鴻翔) 1976 p.1, citing Wei Juxian 1939, “Qín-Hàn shi fāxiàn jiǎgǔwén shuō”, in Shuōwén Yuè Kān, vol. 1, no.4; and He Tianxing 1940, "Jiǎgǔwén yi xianyu gǔdài shuō”, in Xueshu (Shànghǎi), no. 1

- ^ Fairbank, 2006, p. 33.

- ^ Xu Yahui p.4-5 cites The Compendium of Materia Medica and includes a photo of the relevant page and entry.

- ^ Xu Yahui p.4

- ^ Xu Yahui p.4

- ^ Xu Yahui p.4

- ^ Xu Yahui p.4

- ^ Xu Yahui p.16

- ^ Xu Yahui p.4

- ^ Xu Yahui p.6 cites eight waves of illegal digs over three decades, with tens of thousands of pieces taken.

- ^ Zhou 1976, p.1

- ^ Rev. Chalfant acquired 803 oracle bone pieces between 1903 and 1908, and hand-traced over 2500 pieces including these. Zhōu 1976, p.1-2.

- ^ Xu Yahui p.6

- ^ Wang Haiping (2006). "Menzies and Yin-Shang Culture Scholarship – An Unbreakable Bond." Anyang Ribao (Anyang Daily), August 12, 2006, p.1

- ^ See Linfu Dong (2005). Cross Culture snd Faith: the Life and Work of James Mellon Menzies. Toronto: University of Toronto Press

- ^ Geoff York (2008). "The unsung Canadian some knew as 'Old Bones' James Mellon Menzies, a man of God whose faith inspired him to unearth clues about the Middle Kingdom." Globe and Mail, January 18,2008, p. F4-5

- ^ Xu Yahui, p.9

- ^ over 100,000 pieces have been found in all (Qiu 2000, p.61; Keightley 1978, p.xiii)

- ^ Eleven royal-sized tombs were found --Xu Yahui p.10; note that this exactly matches the number of kings who should have been buried at Yīn (the 12th king died in the Zhou conquest and would not have received a royal burial).

- ^ Keightley 1978, p.9 – the female shells are smoother, flatter and of more uniform thickness, facilitating pyromantic use.

- ^ According to Zhōu 1976 p.7, only four rib bones have been found.

- ^ such as ox humerus or astragalus (ankle bone); see Zhōu 1976, p.1

- ^ Xu Yahui p.34 shows a large, clear photograph of a piece of inscribed human skull in the collection of the Institute of History and Philology at the Academia Sinica, Taiwan, presumably belonging to an enemy of the Shang.

- ^ Keightley 1978, p.7; note that there appears to be some confusion in published reports between inscribed bones in general, and bones which have actually been heated and cracked for use in divination

- ^ Keightley 1978, p.7, note 21; Xu Yahui p.35 does show an inscribed deer skull, thought to have been killed by a Shang king during a hunt.

- ^ Keightley 1978, p.3

- ^ Keightley 1978 p.8

- ^ Keightley 1978, p.8

- ^ Keightley 1978, p.10

- ^ Keightley 1978, p.9; Xu Yahui p.22. Some cattle scapulae were also tribute (Xu Yahui p.24.)

- ^ Keightley 1978, p.12 mentions reports of Xiǎotún villagers finding hundreds of shells of all sizes, implying live tending or breeding of the turtles onsite.

- ^ Keightley 1978, p.11