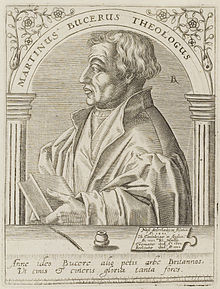

Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer (or Butzer[1]) (11 November 1491 – 28 February 1551) was a Protestant reformer whose principal ministry was in Strasbourg.

Early years (1491–1523)

Martin Bucer was born in Sélestat (Schlettstadt), Alsace, a free imperial city of the Holy Roman Empire.[2] His father, Claus Butzer, Jr., and grandfather, Claus Butzer, Sr., were coopers (barrelmakers) by trade. Nothing is known about Bucer’s mother except that her name was Eva. It was likely that he attended Sélestat’s Latin school where children of artisans sent their children. By the time he completed his studies in the summer of 1507, he was able to read and speak Latin fluently and was familiar with Aristotelian logic and its philosophical system. In the same year, he joined the Dominican order. Bucer claimed in later years that he was forced into the order by his grandfather. What is known is that Bucer's family did not plan for him to learn a craft and they did not have enough money to provide a university education. Hence, the Dominicans provided Bucer a path toward social advancement. After a year of being a novice, he was consecrated as an acolyte in the Strasbourg church of the Williamites and in 1508 he took his vows to become a full Dominican monk. By 1510 he was consecrated as a deacon.[3]

Bucer was sent to study at Heidelberg. There he became acquainted with the works of Erasmus and Protestant Luther, and was present at a disputation of the latter with some of the Romanist doctors. He became a convert to the reformed opinions, then abandoned his order, still by papal dispensation, in 1521, and soon afterwards married a former nun, Elisabeth Silbereisen.

In 1522 he was pastor at Landstuhl in the Palatinate, and travelled broadly propagating the reformed doctrine of Protestantism.

Preacher in Strasbourg

After his excommunication in 1523 he made his headquarters at Strassburg, where he succeeded Matthew Zell. Henry VIII of England asked his advice in connection with the divorce from his wife Catherine of Aragon.

After the death of his first wife, in 1542 he married Wibrandis Rosenblatt the widow of the Reformers Johannes Oecolampadius and Wolfgang Fabricius Capito.

On the question of the sacrament of the Lord's Supper, Bucer's opinions were decidedly Zwinglian, being the author of the Tetrapolitan Confession, but he was anxious to maintain church unity with the Lutheran party and constantly endeavoured — especially after Zwingli's death — to formulate a statement of belief that would unite Lutheran, south German and Swiss reformers; hence, the charge of ambiguity and obscurity which has been laid against him. After the failure of the Marburg Colloquy of October, 1529 to bring about such a union, Bucer himself persisted in seeking agreement with the Lutheran reformers. Such an agreement, the Wittenberg Concord, was concluded on May 29, 1536. The south German signatories were Bucer, Wolfgang Fabricius Capito, Matthäus Alber, Martin Frecht, Jakob Otter, and Wolfgang Musculus. The Lutheran signatories were Martin Luther, Philipp Melanchthon, Johannes Bugenhagen, Justus Jonas, Caspar Cruciger, Justus Menius, Friedrich Myconius, Urban Rhegius, George Spalatin. Later Bucer disavowed the agreement due to his differences with the Lutherans over the interpretation of manducatio indignorum (that "unworthy communicants" also eat and drink the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist). Bucer held that such "unworthy communicants" could only be Christians, though "unworthy" due to impenitence. The Lutherans held that "unworthy" communicants included unbelievers as well.

In 1548 he was sent for to Augsburg to sign the agreement, called the Augsburg Interim, between the Catholics and Protestants. His stout opposition to this project exposed him to many difficulties, and he was glad to accept Cranmer's invitation to make his home in England and assist with the Reformation of the Church of England. On his arrival in 1549 he was appointed Regius Professor of Divinity at Cambridge. Edward VI and the protector Somerset showed him much favour and he was consulted as to the revision of the Book of Common Prayer. But on February 28, 1551 he died, and was buried in the university church, with great state.

Theology and Marian views

Bucer, who is considered to have been one of the most influential and important Protestant theologians of his time, was not always clear to conflicting views of Luther and Zwingli. [4] He wrote his main theological work, De Regno Christi in two large volumes for King Edward VI. He did not live to see his larger ten volume treatise on theology, of which only the first volume was published. In the year 1530, he published a summary of his theology Confessio Tetrapolitana. [5]

The confession is noteworthy as it contains his views on the relations of Christ to his mother Mary. Bucer believed that the “Blessed Virgin Mary gave birth to Jesus”, through the Holy Spirit". [6] Bucer encouraged Protestant veneratation of Mary, “because the Mother of God should be honoured most industriously”. This can only happen according to Bucer, “if one does, what she demands, most of all, purity, innocence and piety, for which she gave such wonderful examples”. [7] Bucer believed in the perpetual virginity of Mary, who in his view, lives now in glory with her son in heaven, where together with the saints prays for us. Bucer asks Protestants not for prayers to Mary, but for praying the Hail Mary in order to honour her. Like Martin Luther, he supports three Marian holidays. [8]

Legacy

In 1557 Catholic Queen Mary's commissioners exhumed and burnt his body (along with that of Paul Fagius, also considered an heretic) and demolished his tomb; it was subsequently restored by order of Queen Elizabeth I. Bucer is said to have written ninety-six treatises, among them a translation and commentary of the Psalms (one of the first of its kind from the Hebrew text published in 1529), Grund und Ursach (a detailed account of Strassburg reforms to the Roman Mass published in 1524) and De regno Christi (his last major publication; written for Edward VI in 1550). His name is familiar in English literature from the use made of his doctrines by Milton in his divorce treatises.

Works

Bucer's collected writings are being published in three series: the Opera Latina edited by Francois Wendel et al (1955-), the Deutsche Schriften edited by Robert Stupperich et al (1960-), and the correspondence, edited by Jean Rott et all (1979-). Many of his biblical commentaries (among his most important writings) remain without a modern edition. A volume known as the Tomus Anglicanus (Basel, 1577) contains his works written in England.

Notes

- ^ Selderhuis 1999, p. 51; Greschat 2004, pp. 10, 273. When Bucer wrote in German, he used his original name, "Butzer". The Latin form of his name is "Bucerus" and modern scholars have opted to use the abbreviation of the Latin form, "Bucer".

- ^ Selderhuis 1999, p. 51; Greschat 2004, pp. 1, 10–13

- ^ Greschat 2004, pp. 14–16

- ^ Algermissen Martin Butzer (Bucer), in Marienlexikon, Eos, St.Ottilien, 1988, 621

- ^ Algermissen 621

- ^ Algermissen 621

- ^ Algermissen 621

- ^ Algermissen 621

References

- Burnett, Amy Nelson. (1994), The Yoke of Christ: Martin Bucer and Christian Discipline, Kirksville, Missouri: Sixteenth Century Journal Publishers, Inc., ISBN 0-940474-28-X

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help). - Greschat, Martin (2004), Martin Bucer: A Reformer and His Times, Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN 0-664-22690-6

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help). Translation from the original Martin Bucer: Ein Reformator und seine Zeit, Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich, 1990. - Poll, G. J. van de (1954), Martin Bucer's Liturgical Ideas, Assen, Netherlands: Koninklijke Van Gorcum & Comp. N.V., OCLC 1068276

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help). - Selderhuis, H. J. (1999), Marriage and Divorce in the Thought of Martin Bucer, Kirksville, Missouri: Thomas Jefferson University Press, ISBN 0-943549-68-X

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help). Translation from the original Huwelijk en Echtscheiding bij Martin Bucer, Uitgeverij J. J. Groen en Zoon BV, Leiden, 1994. - Spijker, Willem van ’t (1996), The Ecclesiastical Offices in the Thought of Martin Bucer, Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill, ISBN 9004102531

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help). - Thompson, Nicholas (2004), Eucharistic Sacrifice and Patristic Tradition in the Theology of Martin Bucer 1534-1546, Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill N.V., ISBN 9004141383

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help). - Wright, D. F., ed. (1994), Martin Bucer: Reforming church and community, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 052139144X.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)