Islamic views on slavery

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

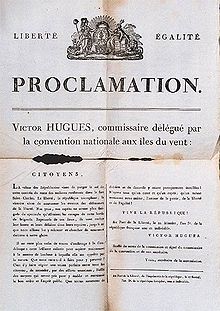

Islam and slavery, documents Islam's approach to slavery and the status of slaves within Islamic society. Islam, like Judaism, Christianity and other world religions, accepted and even endorsed the institution of slavery.[1] Muhammad and those of his Companions who could afford it themselves owned slaves, and some of them acquired more by conquest. However, the Islamic dispensation enormously improved the position of the Arabian slave through the reforms of a humanitarian tendency both at the time of Muhammad and the later early caliphs.[1] The legal legislations brought two major changes to the practice of slavery inherited from antiquity, from Rome, and from Byzantium, which were to have far-reaching effects. Bernard Lewis, a distinguished Islamic historian, considers these reforms to be the cause of the vast improvements in the practice of slavery in Muslim lands. The reforms also seriously limited the supply of new slaves.[1]

The Qur'an considers emancipation of a slave to be a meritorious deed, or as a condition of repentance for certain sins. The Qur'an and Hadith contain numerous passages supporting this view. Muslim jurists considered slavery to be an exceptional circumstance, with the basic assumption of freedom until proven otherwise. Furthermore, as opposed to pre-Islamic slavery, enslavement was limited to two scenarios: capture in war, or birth to slave parents (birth to parents where one was free and the other not so would render the offspring free).[2]

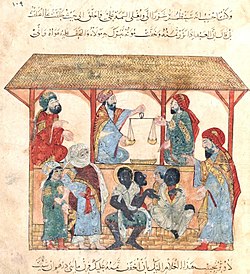

Slavery in Islam does not have racial or color component, although this ideal has not always been put into practice. Nevertheless, historically, black slaves could rise to important positions in Muslim nations.[3][4] In early Islamic Arabia, Slaves were often African blacks from across the Read sea, but by expansion of the Islamic empire in later times, slaves could be Berbers from North Africa, Slavs from Europe, Turks from Central Asia, or Circassians from the Caucasus. [5] The majority of slaves throughout the history of Arabia were, however, of African origin. The Arab slave trade was most active in eastern Africa, although by the end of the 19th century such activity had reached a significantly low ebb. It was in the early 20th century (post World War I) that slavery gradually became outlawed and suppressed in Muslim lands, largely due to pressure exerted by Western nations such as Britain and France.[2]

Pre-Islamic slavery

Slavery was widely practiced in pre-Islamic Arabia, as well as in the rest of ancient and early medieval world. The majority of slaves within Arabia were of Ethiopian origin, through whose sale merchants grew rich. The minority were white slaves of foreign race, likely brought in by Arab caravaneers (or the product of Bedouin captures) stretching back to biblical times. Native Arab slaves had also existed, a prime example being Zayd ibn Harithah, later to become Muhammad's adopted son. Arab slaves, however, usually attained as captives, were generally ransomed off amongst nomad tribes.[2] The slave population was recruited by the abandonment, kidnapping or sale of small children. Free persons were also able to sell their offspring, or even themselves, into slavery. Enslavement was also possible due to legal offences of the law, as in the Roman Empire.[6]

Two classes of slave were apparent: A purchased slave, and a slave born in the master's home— the latter over whom the master had complete rights of ownership, although was unlikely to be sold or disposed of by the master. Female slaves were at times prostituted for the benefit of their masters in accordance with Near Eastern customs, the practice of which is condemned in the Qur'an [Quran 24:33].[2][7] [8]

Slavery in Islamic society

The Qur’an, like the Old and the New Testaments, assumes the existence of slavery, Bernard Lewis states.[1] The Qur'an regulates the practice of the institution and thus implicitly accepts it. Lewis also notes that slavery was a feature of the ancient times and for example both the Old and New Testaments recognize and accept the institution of slavery. Lewis points out that the Islamic legislation "brought two major changes to ancient slavery which were to have far-reaching effects: "the presumption of freedom" and "the ban on the enslavement of free persons except in strictly defined circumstances". [1] Muslim jurists defined slavery as an exceptional condition, with the general rule being a presumption of freedom (al-'asl huwa 'l-hurriya — "The basic principle is liberty") for a person if his origins were unknown. Furthermore, lawful enslavement was restricted to two instances: capture in war (on the condition that the prisoner is not a Muslim), or birth in slavery. Islamic law did not recognize the two classes of slave from pre-Islamic Arabia.[2]

Slavery in Islamic jurisprudence

Treatment

Although slavery itself was not abolished by the Qur'an, Muslims were admonished to treat their slaves well: In the instance of illness, for example, it would be required for the slave to be looked after. Slave manumission (declaring the slave to be free) would be considered a meritorious act, although the slave would be eligible to ransom himself with the money he has earned while conducting his own business. Slave owners were encouraged to allow their slaves to earn their freedom, and to "give them some of God's wealth which He has given you" ([Quran 24:33]).[8] Azizah Y. al-Hibri, a professor of Law specializing in Islamic jurispundence, states that both the Qur’an and Hadith are repeatedly exhorting Muslims to treat the slaves well and that Muhammad showed this both in action and in words.[9] Al-Hibri supports her assertion by quoting a tradition from Ibn Hisham in which Muhammad made Bilal, an Ethiopian slave, to be a mu’ath.thin (a person who calls for prayers) of all Muslims, to envy of many Arabs. Al-Hibri also quotes the famous last speech of Muhammad and other hadiths emphasizing that all believers, whether free or enslaved, are siblings. [9] Lewis explains, "the humanitarian tendency of the Qur'an and the early caliphs in the Islamic empire, was to some extent counteracted by other influences,"[1] notably the practice of various conquered people and countries Muslims encountered, especially in provinces previously under Roman law (even the Christianized form of slavery was still harsh in its treatment of slaves). In spite of this, Lewis also states, "Islamic practice still represented a vast improvement on that inherited from antiquity, from Rome, and from Byzantium."[1]

Legal status

Within Islamic jurisprudence, slaves are able to occupy any office within the Islamic government, and instances of this in history include Eunuchs(castrated human male) having held military and administrative positions of note.[10] They are also able to marry, own property, and lead the Muslim congregational prayers (the five daily ritual prayers).[11] Annemarie Schimmel, a contemporary scholar on Islamic civilization, asserts that because the status of slave under Islam could only be obtained through either being a prisoner of war (this was soon restricted only to infidels captured in a holy war)[1] or born from slave parents, slavery would be theoretically abolished with the expansion of Islam.[10] Islam's reforms seriously limited the supply of new slaves, according to Lewis.[1] In the early days of Islam, he notes, a plentiful supply of new slaves were brought due to rapid conquest and expansion. But as the frontiers were gradually stabilized, this supply dwindled to a mere trickle. The prisoners of later wars between Muslims and Christians were commonly ransomed or exchanged.[1] Azizah Y. al-Hibri argues that the Qur'an recognized slavery as an undesirable socio-political condition and spelled out many ways for its elimination.[12] Patrick Manning, a professor of World History, states that Islamic legislations against the abuse of the slaves convincingly limited the extent of slavery in Arabian peninsula and to a lesser degree for the whole area of the whole Umayyad Caliphate where slavery existed since the most ancient times. He however notes that with the passage of time and the extension of Islam, Islam by recognizing and codifying the slavery seems to have done more to protect and expand slavery than the reverse. [13]

Theoretically, free-born Muslims could not be enslaved, and the only way that a non-Muslim could be enslaved was being captured in the course of holy war. [14] (In early Islam, neither a Muslim nor a Christian or Jew could be enslaved.[15]) Slavery was also percieved as a means of converting non-Muslims to Islam: A task of the masters was Religious instructions. Although conversion and assimilation into the society of the master didn't automatically lead to emancipation but there was normally some guarantee of better treatment and was deemed a prerequisite for emancipation [16]

The property of the slave technically was owned by the master unless a contract of freedom of the slave had been entered into, which allowed the slave to earn money to purchase his freedom and similarly to pay bride wealth. The marriage of slaves required the consent of the owner. Under the Hanafi and Shafai schools of jurisprudence male slaves could marry two wives, but the Maliki permitted them to marry four wives like the free men. According to the Islamic law, a male slave could marry a free woman but this was discouraged in practice. [14] Islam permits intimate relations between a male master and his female slave outside of marriage referred to in the Qur'an as ma malakat aymanukum or "what your right hands possess"[17][18]), although he may not co-habit with a female slave belonging to his wife.[2] Neither can he have relations with a female slave if she is co-owned, or already married. If the female slave has a child by her master, she then receives the title of "Umm Walad" (lit. Mother of a child), which is an improvement in her status as she can no longer be sold and is legally freed upon the death of her master. The child, by default, is born free due to the father (i.e. the master) being a free man. Although there is no limit on the number of concubines a master may possess, the general marital laws are to be observed, such as not having intimate relations with the sister of a female slave.[2] [16] The concubines, under the Islamic law, had an intermediate position between slave and free.[16] In Islam, "men are enjoined to marry free women in the first instance, but if they cannot afford the bridewealth for free women, they are told to marry slave women rather than engage in wrongful acts." [19] Another rationalization given for recognition of concubinage in Islam is that "it satisfied the sexual desire of the female slaves and thereby prevented the spread of immorality in the Muslim community." Concubinage was only allowed as a monogamous relation between the slave woman and her master [20], however, in reality in many Muslim societies, female slaves were prey for members of their owners' household, their neighbors, and their guests. [21]

In certain legal punishments, a slave would be entitled to half the penalty required upon a freeman. For example: where a free man would be subject to a hundred lashes due to pre-marital relations, a slave would be subject to only fifty. Other cases however, as with theft or apostasy, require the same punishment upon the slave as the free man, as long as the necessary conditions for such punishments are fulfilled.[2]

Slavery in Islamic texts

Qur'an

Hadith

A hadith attributed to Abu Hurairah Allah's Messenger (may peace be upon him) as saying: "He who emancipates a slave, Allah will set free from Hell every limb (of his body) for every limb of his (slave's) body, even his private parts." Template:Muslim reports:[citation needed]

Treatment of the captive

A hadith attributed to Abu Sa’eed al-Khudri The Prophet (peace and blessings of Allaah be upon him) said, concerning the prisoners of Awtaas: “Do not have intercourse with a pregnant woman until she gives birth, or with one who is not pregnant until she has menstruated once.” Sunan Abu Da'ud, 2157[22] reports:[citation needed]

A hadith attributed to Zadhan Ibn Umar called his slave and he found the marks (of beating) upon his back. He said to him: I have caused you pain. He said: No. But he (Ibn Umar) said: You are free. He then took hold of something from the earth and said: There is no reward for me even to the weight equal to it. I heard Allah's Messenger (may peace be upon him) as saying: He who beats a slave without cognizable offence of his or slaps him (without any serious fault), then expiation for it is that he should set him free. Template:Muslim reports:[citation needed]

A hadith attributed to Abu Mas'ud al-Badri I was beating my slave with a whip when I heard a voice behind me: Understand, Abu Masud; but I did not recognise the voice due to intense anger. He (Abu Mas'ud) reported: As he came near me (I found) that he was the Messenger of Allah (may peace be upon him) and he was saying: Bear in mind, Abu Mas'ud; bear in mind. Abu Mas'ud. He (Aba Maslad) said: threw the whip from my hand. Thereupon he (the Holy Prophet) said: Bear in mind, Abu Mas'ud; verily Allah has more dominance upon you than you have upon your slave. I (then) said: I would never beat my servant in future. Template:Muslim reports:[citation needed]

A hadith attributed to Ma'rur b. Suwaid I saw Abu Dharr wearing clothes, and his slave wearing similar ones. I asked him about it, and he narrated that he had abused a person during the lifetime of Allah's Messenger (may peace be upon. him) and he reproached him for his mother. That person came to Allah's Apostle (may peace be upon him) and made mention of that to him. Thereupon Allah's Apostle (may peace be upon him) said: You are a person who has (remnants of) Ignorance in him. Your slaves are brothers of yours. Allah has placed them in your hand, and he who has his brother under him, he should feed him with what he eats, and dress him with what he dresses himself, and do not burden them beyond their capacities, and if you burden them, (beyond their capacities), then help them. Template:Muslim reports:[citation needed]

Abolition of Slavery

In 19th century, the revolution against slavery gave rise to a strong abolitionist movement of slavery in England and later in other Western countries, gradually taking hold in Muslim lands. Contrasting with ancient and colonial systems, slaves in Muslim lands had a certain legal status and had obligations to as well as rights over the slave owner. Slavery was not only recognized but was elaborately regulated by Sharia law. Although emancipation of slaves was recommended, it was not compulsory. Lewis eludicates that it was for this reason that "the position of the domestic slave in Muslim society was in most respects better than in either classical antiquity or the nineteenth-century Americas", and that the situation of such slaves were no worse than (and even in some cases better than) free poors[23]. However, the processes of acquisition and transportation of slaves to Muslim lands often imposed appalling hardships, though "once the slaves were settled in Islamic culture they had genuine opportunities to realize their potential. Many of them became merchants in Mecca, Jedda, and elsewhere." The hardships of acquisition and transportation of slaves to Muslim lands drew attention of European opponents of slavery. The continuing pressure from European countries eventually overcame the strong resistance of religious conservatives who were holding that forbidding what God permits is just as great an offense as to permit what God forbids. Slavery, in their eyes, was "authorized and regulated by the holy law". Eventually, the Ottoman empire's orders against the traffic of slaves were issued and put into effect. [23]

Muslim scholar Javed Ahmed Ghamidi writes in his book Mizan that Qur'an gave slaves the right to make contract with their masters according to which they would be required to pay a certain sum of money in a specific time period, or would carry out a specific service for their masters (mukatabat); once they would successfully fulfill either of these two options, they would stand liberated. [24] As stated in Qur'an:

This right of mukatabat was granted to slave-men and slave-women. Prior to this, various other directives were given at various stages to gradually reach this stage. These steps are summarized below:[24]

- In the very beginning of its revelation, the Qur'an regarded emancipation of slaves as a great virtue.[25]

- People were urged that until they free their slaves they should treat them with kindness.[26][27]

- In cases of unintentional murder, Zihar(see footnote for definition) [28], and other similar offences, liberating a slave was regarded as their atonement and charity.[29]

- It was directed to marry off slave-men and slave-women who were capable of marriage so that they could become equivalent in status, both morally and socially, to other members of society.[30]

- If some person were to marry a slave-woman of someone, great care was exercised since this could result in a clash between ownership and conjugal rights. However, such people were told that if they did not have the means to marry free-women, they could marry, with the permission of their masters, slave-women who were Muslims and were also kept chaste. In such marriages, they must pay their dowers so that this could bring them gradually equal in status to free-women.[31]

- In the heads of Zakat (Legal almsgiving, Islamic religious tax), a specific head (for freeing necks [emancipation of slaves]) was instituted so that the campaign of slave emancipation could receive impetus from the public treasury.[32]

- Fornication (sexual intercourse between a man and a woman who are not married to each other) was regarded as an offence. Since prostitution centers around this offence, brothels that were operated by owners using their slave-women were shut down automatically, and if someone tried to go on secretly running this business, he was given exemplary punishment.[33]

- People were told that they were all slaves/servants of Allah and so instead of using the words عَبْد (slave-man) and اَمَة (slave-woman), the words used should be فَتَى (boy/man) and فَتَاة (girl/woman) so that the psyche about them should change and a change is brought about in these age-old concepts.[34]

- A major source of slaves within the institution of slavery at the advent of Islam were the prisoners of war. The Qur'an rooted this out by legislating that prisoners of war should be freed at all costs, either by accepting ransom or as a favour by not taking any ransom money. No other option was available to the Muslims.[35][36]

Slavery in Sudan

John Eibner of Christian Solidarity International, as quoted by the American Anti-Slavery Groups, gives the following description of slavery in Sudan:

"It begins when the armed forces of the government-backed mujadeen, or allied militias, raid a southern Sudanese village. They kill men on the spot, beat the elderly, and capture the women and children. Raiders and their victims start the horrific march to the North. Children are executed when they cry. People who try to run away are shot. The young girls are taken by soldiers into the bush and gang raped.

"Each victim later becomes one of two kinds of slaves, a house slave or a field slave. House slaves cook, clean, fetch water and firewood, and do other household chores. The field slaves cultivate the land, weed, and tend to livestock. Children usually tend cows and goats. But all slaves are mocked, insulted, threatened, and beaten into submission.

"Some masters are simply interested in labor and do not convert slaves to Islam. Other masters teach slaves Islam and give their slaves Muslim names. Many female slaves are subjected to genital mutilation or circumcision - a rite of passage for some Muslims, but something not practiced by the Dinka." [1]

The going price of a "servant" (as slaves are called there) is $20 to $25 (USD equivalent).

According to CNN, Christian groups in the United States have expressed concern about slavery and religious oppression against Christians by Muslims in Sudan, putting pressure on the Bush administration to take action. [2]

Oriental slave trade

The oriental slave trade is sometimes called Islamic slave trade, but religion was hardly the point of the slavery, Patrick Manning, a professor of World History, states. [37] Also, this term suggests comparison between Islamic slave trade and Christian slave trade. Furthermore, usage of the terms "Islamic trade" or "Islamic world" implicitly and erroneously treats Africa as it were outside of Islam, or a negligible portion of the Islamic world.[37]

In the 8th century Africa was dominated by Arab-Berbers in the north: Islam moved southwards along the Nile and along the desert trails. The Solomonic dynasty of Ethiopia often exported Nilotic slaves from their western borderland provinces, or from newly conquered or reconquered Muslim provinces. Native Muslim Ethiopian sultanates (rulership) exported slaves as well, such as the sometimes independent sultanate (rulership) of Adal (a sixteenth century province-cum-rulership located in East Africa north of Northwestern Somalia).[38] On the coast of the Indian Ocean too, slave-trading posts were set up by Arabs and Persians. The archipelago of Zanzibar, along the coast of present-day Tanzania, is undoubtedly the most notorious example of these trading colonies. East Africa and the Indian Ocean continued as an important region for the Oriental slave trade up until the 19th century.[2] Livingstone and Stanley were then the first Europeans to penetrate to the interior of the Congo basin and to discover the scale of slavery there.[39] The Arab Tippu Tib extended his influence and made many people slaves.[39] After Europeans had settled in the Gulf of Guinea, the trans-Saharan slave trade became less important. In Zanzibar, slavery was abolished late, in 1897, under Sultan Hamoud bin Mohammed.[40] The rest of Africa had no direct contact with Muslim slave-traders.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lewis 1994, Ch.1 Cite error: The named reference "Lewis" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Brunschvig. 'Abd; Encyclopedia of Islam

- ^ Lewis (1992) p. 19, 74

- ^ The famous medieval jurist al-Ghazzali denounced the perception of a white man being better than a black one as adopting the same hierarchical principles of ignorance endorsed by Satan: something which al-Ghazzali believes would eventually result in polytheism. cf. Azizah Y. al-Hibri, 2003

- ^ Bloom and Blair (2002) p. 48

- ^ Lewis (1992) p. 4

- ^ Mendelsohn (1949) pp. 54—58

- ^ a b John L Esposito (1998) p. 79

- ^ a b c Azizah Y. al-Hibri, 2003

- ^ a b Schimmel (1992) p. 67

- ^ Esposito (2002) p.148

- ^ Azizah Y. al-Hibri, 2003. The footnote of the article references to the discussion of ABD AL-WAHID WAFI, HUQUQ AL-INSAN FI AL-ISLAM (Cairo: Nahdhat Misr 1999) at 156-164; see also Muhammad ‘Amarah, Al-Islam Wa Huquq Al-Insan (Cairo: Dar al-Shuruq 1989), pp. 18-22.

- ^ Manning (1990) p.28

- ^ a b Sikainga (1996) p.5

- ^ John Esposito (1998) p.40

- ^ a b c Paul Lovejoy (2000) p.2

- ^ See Tahfeem ul Qur'an by Sayyid Abul Ala Maududi, Vol. 2 pp. 112-113 footnote 44; Also see commentary on verses [Quran 23:1]: Vol. 3, notes 7-1, p. 241; 2000, Islamic Publications

- ^ Tafsir ibn Kathir 4:24

- ^ Nashat (1999) p. 42

- ^ Bloom and Blair (2002) p.48

- ^ Sikainga (1996) p.22

- ^ This hadeeth was classed as saheeh by Shaykh al-Albaani in Irwa’ al-Ghaleel, 187.

- ^ a b Bernard Lewis, (1992), pp. 78-79

- ^ a b Ghamidi, Chapter: The Social Law of Islam

- ^

Quran - ^ Sahih Muslim,1662, 1661, 1657, 1659

- ^ Sunan Abu Dawud, 5164

- ^ A particular form of severing relationship with one's wife. In this form, the man would declare something to the effect that his wife shall from now on be like a mother to him, as mentioned in

Quran - ^

, [Quran 58:3], [Quran 5:89]Quran - ^ 24:32

- ^

Quran - ^

Quran - ^ Ghamidi, The Penal Law of Islam

- ^ Sahih Muslim, 2249

- ^

Quran - ^ Ghamidi, Islamic Law of Jihad

- ^ a b Manning (1990) p.10

- ^ Pankhurst (1997) p. 59

- ^ a b Holt et. al (1970) p.391

- ^ Ingrams (1967) p.175

References

- P.J. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs (ed.). "Abd". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill Academic Publishers. ISSN 1573-3912.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Al-Hibri, Azizah Y. (2003). "An Islamic Perspective on Domestic Violence". 27 Fordham International Law Journal 195.

- Bloom, Jonathan; Blair, Sheila (2002). Islam: A Thousand Years of Faith and Power. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300094221.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Esposito, John (1998). Islam: The Straight Path. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195112334. - First Edition 1991; Expanded Edition : 1992.

- Javed Ahmed Ghamidi (2001). Mizan. Lahore: Al-Mawrid. OCLC: 52901690.

- Ed.: Holt, P. M ; Lambton, Ann; Lewis, Bernard (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521291372.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ingrams, W. H. (1967). Zanzibar. UK: Routledge. ISBN 0714611026.

- Lewis, Bernard (1992). Race and Slavery in the Middle East. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195053265.

- Lovejoy, Paul E. (2000). Transformations in Slavery. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521784301.

- Manning, Patrick (1990). Slavery and African Life: Occidental, Oriental, and African Slave Trades. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521348676.

- Mendelsohn, Isaac (1949). Slavery in the Ancient Near East. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 67564625.

- Pankhurst, Richard (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. The Red Sea Press. ISBN 0932415199.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1992). Islam: An Introduction. US: SUNY Press. ISBN 0791413276.

- Sikainga, Ahmad A. (1996). Slaves Into Workers: Emancipation and Labor in Colonial Sudan. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0292776942.

- Tucker, Judith E.; Nashat, Guity (1999). Women in the Middle East and North Africa. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253212642.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Race and Slavery in the Middle East by Bernard Lewis