Khosr

|

Khosr نهر الخوصر / Nahr al-Khosr |

||

|

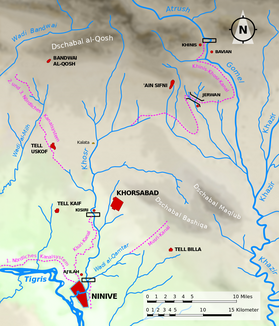

Course of the Khosr, the location of old cities and Sennacheribs hydraulic structures |

||

| Data | ||

| location | Ninawa Province , Iraq | |

| River system | Shatt al-Arab | |

| Drain over | Tigris → Shatt al-Arab → Persian Gulf | |

| Start by name | Confluence of two wadis 36 ° 36 ′ 13 ″ N , 43 ° 11 ′ 47 ″ E |

|

| Source height | approx. 318 m | |

| muzzle | At Mosul in the Tigris coordinates: 36 ° 20 '43 " N , 43 ° 8' 27" E 36 ° 20 '43 " N , 43 ° 8' 27" E |

|

| Mouth height | approx. 211 m | |

| Height difference | approx. 107 m | |

| Bottom slope | approx. 2.3 ‰ | |

| length | approx. 47 km | |

The Khosr is a 47 kilometer long wadi in the Ninawa Governorate in northwest Iraq . It is one of the largest of the tributaries of the Tigris that do not have constant water and to which it flows orographically on the right.

Names

The full name is in Arabic (نهر الخوصر / Nahr al-Khosr ). Both the article "ال / al- "as well as the expression"نهر / Nahr “for river, canal do not necessarily have to be placed in front. Langenscheidt's Arabic-German dictionary translates the term horn into the meaning of the brass instrument. In addition, there are many different name variants that are explained by transcriptions into different languages according to different rules. In more recent German sources the following spellings are used: Chosr, Ḫosr, Hausr, Khosr, Khoser , in older sources also Choser, Chusur, Khauser . The French translation includes Koussour and Khosar, Khausser or Hosrow in English transcriptions. Other forms of the name in other languages are: Khosar, Khasar, Khawsar, Kawarsar , sometimes together with the introductory name Wadi, such as " Wadi al Khawşar ".

course

The river arises in the hilly foothills at the southern foot of the Jabal al-Qosh mountain range near the Sunni - Kurdish village of Xorekor from the confluence of two multi-branched wadis. The western tributary is called Nahr 'Ayn Zawah (نهر عين زاوة), the eastern one is as Rubar Kitak روبار كتكknown. After the union of the two source streams, the Khosr flows through the northeastern part of the Nineveh Plain in many meanders and after about 15 kilometers in a southerly direction passes the ancient fortifications of Dur Šarrukin on its eastern bank . A little further down the river lie the remains of a dam that formed the head of the 16-kilometer-long Kisiri Canal, first mentioned in 702 BC, which ran parallel to the river as far as the city walls of Nineveh .

After another eight kilometers, the river accumulates at the place Mintaqat ash Shalalat (منطقة الشلالات) in front of a weir that is said to go back to an Assyrian dam. From here it is another 17 kilometers to reach the excavations of Nineveh. Some archaeologists have assumed that the river, which rushes when it rains or when snowmelts, was routed around the city in the broad moat in King Sennacherib's time. After more than two and a half millennia, however, this can no longer be proven, and the situation is as follows: The water has broken through the east wall and destroyed part of the former fortifications, but one can still clearly see that the lower part of the wall consists of large Stone blocks. The course of the river takes its way in a south-westerly direction, draws a pronounced loop in front of the settlement hill Tell Kujundschik and leaves the ruined city after a little more than three kilometers to flow into the Tigris after the last two kilometers.

bridges

Within the urban area of Mosul, the following bridges span the Khosr in the order downstream. Several of them were destroyed during the Battle of Mosul . Efforts have been made to rebuild it since the end of the fighting in July 2017.

- The Sugar Bridge (جسر السكر) is part of the Mosul - Lalish expressway .

- The approximately 238 meter long Al ‑ Muthanna Bridge (جسر المثنى) connects the neighborhoods of Al ‑ Muthanna and Al ‑ Zuhour.

- Over the Great Muthanna Bridge (جسر المثنى الكبير) leads one of the busiest streets between the neighborhoods of Al ‑ Muthanna and Al ‑ Noor.

- The flower bridge (جسر الزهور) is about 124 meters long and connects the districts of Al ‑ Muthanna and Al ‑ Zuhour.

- The Al Suez Bridge (جسر السويس) with a length of 269 meters connects the district of Al ‑ Faisaliah with the agricultural areas in the north-west of the city.

- The 180 meter long Sennacherib Bridge (جسر سنحاريب) runs a little further downstream, parallel to the Al Suez Bridge.

History

6th century BC Chr.

At the time of the Assyrian king Sennacherib , the water of the Tigris was probably not drinkable. The so-called Bavian inscription states that “the inhabitants did not know drinking water and their eyes were on the rain falling from the sky”. In order to ensure the water supply of his capital Nineveh even during the dry season, the king realized between 702 and 688 BC. An epochal hydraulic engineering project. The channeling of the Khosr played the most important role. He had the connection to the aqueduct of Jerwan created through his eastern source stream . The water from the Atrush River in the eastern Al ‑ Qosh Mountains in the Khosr came through this 275 meter long overpass, which some researchers consider the oldest of its kind .

From the north-westerly direction water came from the upper reaches of the Wadis Al ‑ Milah (وادي المالح) and Bandwai (بهنداوة) through the Wadi al Abrah (وادي الابرة) directed into the Khosr.

At the instigation of the king , artificial lakes were created at the springs at the foot of Mount Musri (Jabal Bashiqa), about 20 kilometers from Nineveh, near the present-day city of Bashiqa . With the help of sluices, the water could be channeled into the Musri Canal as required. This waterway led into the Wadi al ‑ Qamtar, which flows into the Khosr near above the lock of Aj'ilah.

The construction of tunnels, aqueducts, dams and weirs took a total of fifteen years and created a 150-kilometer-long canal system that allowed the Khosr to be regulated and thus enabled the city to be supplied with drinking water and irrigated arable land.

In his work "The Geography", the geographer Carl Ritter describes the river as the happinesser of Nineveh. The Khosr could also pose a danger, especially during floods, which the far-sighted ruler must have been aware of. The Khosr comes into being with the destruction of the city by the Medes and Babylonians in 612 BC. More or less directly related. This event was foretold by the prophet Nahum from Elkosch and was included in the book of Nahum in the prophetic books of the Torah and thus in the Bible .

The prophecy describes that the walls of the palace are to be destroyed by large amounts of water.

"With the raging tide he puts an end to his adversaries, and he pursues his enemies with darkness."

Perhaps the water could also get into the city at the lock gates to Khosr, as Nahum's text suggests. Who could have opened it remains in the dark.

Some researchers interpret the Bible text to mean that a devastating flood undermined the fortifications; others believe that the besiegers dammed the water in the canals so high that the city walls collapsed. In trying to explain the biblical flood, another possibility would be that the city was not flooded until after the Babylonian victory. To this end, the water reservoirs could have been opened and their contents drained into the Khosr in an uncontrolled manner. At least that is what the text in the book of Nahum (chapter 2, verse 9) suggests, where it says:

“Nineveh is like a full pond, but its waters must run away. "Stand, stand!" You shout, but nobody turns around. "

In 1898 the Innsbruck professor Friedrich questioned the conquest of the city by the Medes. According to his thesis, the end of Nineveh could have been the result of a devastating natural disaster. During a storm, heavy rains, not uncommon in the area, could have caused a dam on the Khosr to collapse, causing the east wall to collapse. A lightning strike could have ignited a fire, which would have been further kindled by the storm, which could explain scorch marks in the ruins. The biblical scholar Aron Pinker, on the other hand, takes the view that the topography of Nineveh excludes the possibility of a flood by the Khosr.

The date and duration of the siege are known from the Babylonian Chronicle No. 3, but no description of the fighting. The role of Khosr is also not mentioned in this source. There it says:

“The king of Akkad gathered his army and united it with the army of Kyaxares , the king of the Medes. They besieged Nineveh from the month of Sivan to the month of Ab - for three months. They set up camp in front of Nineveh and subjected the city to a heavy siege. On ... the day of the month of Ab, they inflicted a great defeat on the mighty [people of Nineveh]. At that time the king of Assyria was Sîn-šarru-iškun [who] was dying. They carried rich booty from the city and the temple and reduced the city to rubble. "

19th century

After the rediscovery of Nineveh by Paul-Émile Botta in 1842 , it became clear that the former capital was not rebuilt after the fall of the Assyrian Empire and that Sennacherib's hydraulic structures had crumbled. This had the consequence that the Khosr fell back to a normal dry valley in terms of flow rate. As with other wadis, the water throughput has been subject to seasonal fluctuations since then.

21st century

The lower course near Mosul has very little water seasonally and is misused as a sewer. An analysis of the river water near the mouth in 2006 revealed a high concentration of heavy metals such as cadmium and copper and contamination with bacteria.

Web links

- Austen Henry Layard: "Discoveries in the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon" . John Murray, London, 1853, ISBN 1-4021-7444-6 ( archive.org ).

- Ariel M. Bagg: "On the waters of Nineveh" . Philipp von Zabern, 2012 ( academia.edu ). (Article in the magazine ANTIKE WELT)

References and comments

- ↑ a b Dr. Mazin N. Fadhel: "Adverse impact of Al-Khoser river upon Tigris river at outfall area" . 2008 ( edu.iq [PDF]).

- ↑ وصر in Langenscheidt: Arabic-German dictionary. Retrieved April 7, 2018 .

- ↑ Restored Assyrian dam on Khosr

- ↑ a b Dr. Thomas Friedrich: "Nineve's Ende" in "Festgabe im Ehren Max Bdinger's" . Verlag der Wagner'schen Universitäts-Buchhandlung, Innsbruck, 1898, ISBN 1-148-36331-9 ( google.de ).

- ↑ Reconstruction of the Sugar and Flower Bridge (English)

- ↑ Bridges in the province of Ninawa (Arabic)

- ↑ Jason Ur: "Sennacherib's Northern Assyrian Canals" . British Institute for the Study of Iraq, 2005, pp. 1 (English, harvard.edu [PDF]).

- ↑ Thorkild Jacobsen, Seton Lloyd: "Sennacherib's Aqueduct at Jerwan" . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, 1935, ISBN 0-226-62120-0 ( uchicago.edu [PDF]).

- ↑ Carl Ritter: "The Geography of Asia" . Verlag der Wagner'schen Universitäts-Buchhandlung, Innsbruck, 1844, ISBN 0-365-17001-1 ( google.de ).

- ↑ Dahlia Shehata: "Babylonians, Hittites and Co. for dummies" . Wiley-VCH, 2015, ISBN 978-3-527-70499-6 ( google.de ).

- ↑ Aron Pinker: "Nahum and the Greek Tradition on Nineveh's Fall" (English)

- ↑ Albert Kirk Grayson: "Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles" . Eisenbrauns, 2000, ISBN 1-57506-049-3 ( google.de ). (Text of the Babylonian Chronicle No. 3 from line 38, English)