Residence permit (Germany)

The residence permit is a residence permit by the laws of Germany since 1 January 2005 Residence Act (core of the Immigration Act ). It is granted for a specific purpose and limited to so-called third-country nationals .

history

international law

A general customary international law principle of granting persons without nationality of the country of residence a right to entry and residence does not exist to this day. In its legal system, each state regulates the legal status of foreigners or foreigners staying on its territory itself. Under customary international law, states are fundamentally permitted to expel foreigners at will, i. H. to order them to leave the state. The only thing that is guaranteed under international law is to grant strangers a certain minimum standard (e.g. right to legal capacity , right to life and physical integrity, protection from cruel and degrading treatment, fair hearing, fair trial, equality in court, protection from expropriation without compensation). Further legal positions must be justified separately by bilateral trade, friendship and settlement agreements or multilateral agreements.

Time until the founding of the empire

The understanding of the foreigner's right to stay, which prevails in international law, goes back in human history to ideas in Greece and ancient Rome that the foreigner was initially viewed as an enemy. He was fundamentally without rights and protection and excluded from public and political rights. In Germanic law, the stranger could be robbed, enslaved or even killed without the perpetrator being held accountable. Only later did he acquire guest status, initially under private law. Whoever took in a guest assured him of protection and assistance. The mainly religiously based custom was regarded as generally mandatory, but only extended to short stays of a few days.

Until the early Middle Ages, the right of foreigners to reside was based on unwritten customary law that was even anti-literate. In addition to tribal and popular law, the law of the sovereign , including state and imperial law, increasingly emerged .

Population growth, pauperization and internal mobility as well as the liberation of peasants in the first half of the 19th century led to tightening of border controls and passport systems as well as stricter control of deportation practice. In 1813, Prussia introduced compulsory passports in general and therefore also for foreigners. Foreigners also required a residence permit in the form of a visa to stay in a municipality for more than 24 hours, without which they were not allowed to be accommodated by the innkeepers designated as non-commissioned officers of the Aliens Police . In 1842 the right to freedom of movement for Prussian citizens was introduced, which was withheld from foreigners because the introduction of the freedom of trade was intended to keep away undesirable, especially impoverished, foreigners. Strangers could be deported at any time if they were or became needy.

Period from 1871 to 1945

With the establishment of the German Empire in 1871, nationals of a German federal state were treated as residents in every other federal state. That did not apply if they were “poor”. Then the law of the Reichsausländer applied to them and they could be expelled. At that time expulsions were possible with effect for a municipality, a country or for the entire territory of the Reich. The prerequisites were not uniform. In Prussia, expulsion was generally considered permissible in the interests of public safety, law and order, as was expulsion of "annoying foreigners". Reasons for deportation could be criminal, police or political. In Prussia, the expulsion of foreign beggars as well as foreign vagrants, beggars and laborers after discharge was provided by law; Incidentally, measures to terminate residence could undisputedly and of course be based on the general police general clause and did not require a special legal basis.

A residence permit for admission to stay in the form of a state document was first introduced in Prussia with the Prussian Aliens Police Ordinance of 1932. At the same time, it limited the reasons for deportation to a conclusive catalog and made binding obstacles and bans on deportation. With its systematics and its existing and protective regulations, it laid the foundation for the later legislation on foreigners in Germany. Every foreigner who either stayed in Prussia for more than six months or wanted to work as an employee, self-employed person or farmer required a residence permit (§ 3).

During the rule of National Socialism - in keeping with the zeitgeist of the time - uniform imperial regulations were introduced, which were found in the Aliens Police Ordinance (APVO) of August 22, 1938. The foreigner police regulations of the federal states have all been repealed (Section 18 (2) c). From then on, residence in the Reich territory was only permitted "for foreigners who, according to their personality and the purpose of their stay in the Reich territory, guarantee that they are worthy of the hospitality granted to them" (§ 1). A formal residence permit was only issued for specific purposes of residence (e.g. as an employee, as a trader, or generally for stays of more than three months) (Section 2). The expulsion was replaced by the prohibition of residence , which could be enacted in nine enumerative case groups as well as in cases of unworthiness within the meaning of Section 1 and extended to family members by way of clan detention (Section 5).

Developments between 1945 and 1990

With the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany, the Aliens Police Ordinance in 1938 essentially continued to apply as an injustice that was not typically National Socialist. It was only replaced by the Aliens Act of April 28, 1965. While the Aliens Police Ordinance of 1938 still differentiated between the entry procedure and the right of residence - the authorization to enter was based solely on the passport law and, here, on the nationality of the person concerned - the Aliens Act 1965 abandoned this distinction. Since then, both the entry permit and the subsequent right to stay have been based solely on the law on foreigners. A passport is still required under aliens law, but primarily as proof of identity and no longer as an entry permit.

The 1965 Aliens Act basically required every foreigner to obtain a formal residence permit. Only people under the age of 16, homeless foreigners and people who were exempt from this under international agreements were exempt from this (Section 2 AuslG 1965).

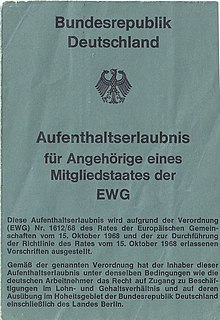

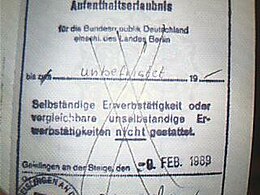

The treaty establishing the European Economic Community on January 1, 1958, caused a serious break in the law on foreigners. The fundamental freedoms enshrined in it , in particular the free movement of workers , significantly changed the national systems of residence rights with regard to community citizens. In the form of Directive 64/221 / EEC of February 25, 1964 and Regulation (EEC) No. 1612/68 of October 15, 1968, national law was overlaid by European law. The law on entry and residence of citizens of the European Economic Community (AufenthG / EEC) of July 22, 1969, which was added in Germany in addition to the Aliens Act 1965 , introduced a special residence permit / EEC , although for a long time it was not always clearly recognized and consistently observed that the primary and secondary community law already finally regulated the residence status of EEC citizens and the German AufenthG / EEC as well as the residence permit / EEC basically only had declaratory significance.

Relatively few foreigners (approx. 190,000) lived in the GDR until the establishment of German unity, mainly students from friendly socialist states and workers who, within the framework of government and foreign trade agreements with Angola , Cuba , Mozambique , Poland and Vietnam for a certain Were employed for a long time in companies in the GDR and then usually returned to their home countries. Neither the constitutions of 1949 and 1968/74 nor the Aliens Ordinance of 1957 and the Aliens Act of 1979 recognized a policy aimed at immigration and mobility for foreigners.

Development after 1990

With the entry into force of the Aliens Act 1990 on January 1, 1991 - while maintaining the residence permit / EEC for community citizens - the always possible connection of the residence permit to a specific purpose of residence (previously mostly by way of ancillary provision) was already expressed in the name. The residence permit became the generic term to which the four forms of residence permit , residence permit , residence permit and residence permit were subordinated. At that time, the purpose of the residence permit was as a rule to stay for employment purposes, i.e. to pursue a professional activity, and for family reunification.

The legislature broke away from this terminology with the Residence Act that came into force on January 1, 2005. Since then, the new generic term has been the residence permit based on European law , which also includes the visa and the special forms of the right of residence based on European law (e.g. the EU Blue Card and the permit for permanent EU residence ). Since January 1, 2005 there are no longer any permanent residence permits; Since then, the residence permit has always been issued for a limited period. Since then, the new permanent residence permit has been the settlement permit .

The sub-forms of residence permits that had been customary in Germany up to that time, with which the purpose of the residence (e.g. for study, family, humanitarian stay, employment) became clear, were abolished and the standard residence permit was returned to. From now on, however, the purpose of the stay must be entered in the residence permit, stating the exact legal basis ( Section 78 subs. 1 sentence 3 no. 8 AufenthG).

The legal basis entered there is of major importance for the question of renewability, but also in other areas of law (e.g. naturalization , basic security [SGB II], child benefit , etc.). A foreigner can - if the prerequisites are met - demand from the immigration authorities that, despite having a valid residence permit, another residence permit with the desired other legal basis is issued. It is even conceivable to have several residence permits at the same time, because each of them grants different rights.

If the purpose no longer applies, the immigration authorities are generally entitled to subsequently shorten the validity of the issued residence permit or to revoke it immediately. Unlike before 2005, the loss of purpose or change of purpose is now fundamentally legally destructive for the future. This tightening is related to the permanent right of permanent residence that has been emerging much more quickly (sometimes after three years). Since the legislature has become more generous here, it pays attention to strict compliance with the earmarking in the preliminary phase. Disputes about the subsequent limitation or the revocation of a residence permit before the deadline expires are now more common in the administrative courts than before.

In the case of EU citizens - more precisely: EEA citizens - the legislature has gone the opposite way: Since the right of free movement is based directly on the treaties on the European Union and is fundamentally permanent from the outset, the residence permit / EEC only had declaratory significance (identity card character ). It was valid for five years when it was issued. In 2005, it was replaced by the unlimited freedom of movement certificate , available on application , until it was also discontinued in January 2013 - and now without replacement. Since then, EEA citizens in Germany do not need a residence permit, a certificate of freedom of movement or any other permit if they make use of their right to freedom of movement under European law (e.g. as an employee, service provider, etc.). All you have to do is prove your citizenship (with an identity card or passport). It is only different if the right to freedom of movement is not used (e.g. when entering retirement age without securing a livelihood at the same time); then, according to the current state of Community law, a residence permit is required again ( Section 11 (1) sentence 11 FreizügG / EU).

It is different for family members of EEA citizens who are not citizens of an EEA country. However, they do not receive a residence permit, but a residence card .

In the case of new accession countries (until recently: Croatia ), there are often transition periods in which a special EU work permit ( Section 284 SGB III) is required for employment . The stay as such does not require a permit after joining.

On the various residence permits and residence situations of today's right of residence → main article residence status (Germany) .

Those affected by the residence permit today

Today, residence permits are only issued to third-country nationals .

Turkish citizens are subject to certain exemptions in their right of residence based on the EEC-Turkey Association Agreement of September 12, 1963 . In principle, the Residence Act applies to them; so they need a residence permit. After a certain period of residence, however, Turkish workers and their family members receive rights similar to free movement within the country in which they live according to the decision 1/80 of the Association Council of the EEC-Turkey . They still need a residence permit; However, this then only has a declaratory meaning, i.e. only the character of an identity card.

Legal basis

The residence permit is regulated in § 7 and § 8 AufenthG and is generally only issued for a limited period and always for a specific purpose (the individual purposes of the stay are listed in §§ 16 to 38 a).

- Residence for the purpose of training ( Sections 16 to 17 a )

- Residence for the purpose of gainful employment ( Sections 18 to 21 )

- Residence for international law, humanitarian or political reasons ( Sections 22 to 26 )

- Residence for family reasons ( Sections 27 to 36 )

- Residence for former Germans and long-term residents in the EU ( Sections 37 to 38 a )

The purpose of the stay is entered in the form of the legal basis in the residence permit.

The residence permit for Turkish citizens who are entitled to association is mentioned in Section 4 (5) of the Residence Act.

Gainful employment

The residence permit is not always associated with a work permit ; this must be expressly stated in the residence permit ( Section 4 subs. 2 and 3 AufenthG). The conditions under which this is possible depend on the purpose of the stay. In many cases, the immigration authorities must first obtain the consent of the Federal Employment Agency ( Sections 39 to 42 of the Residence Act ).

Procedure

Before applying for a residence permit at the Immigration Office has the civil or the registration office of the respective local government a home address for the requesting foreigners are logged.

Form of grant

Since September 1, 2011, the residence permit has been issued as an electronic residence permit in credit card format. The entry of the residence permit in the national passport in the form of a sticker no longer takes place, with rare exceptions ( Section 78a, Paragraph 1 of the Residence Act). Children also need their own check card. The costs for the first issue of a residence permit are between 100 and 110 euros and for an extension between 65 and 80 euros ( Section 44 AufenthV), whereby there are a number of fee exemptions and reductions.

For further details → main article electronic residence permit .

Web links

- Residence Act Act on the residence, employment and integration of foreigners in the federal territory

- General administrative regulation for the Residence Act of October 26, 2009 (PDF; 2 MB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Knut Ipsen: Völkerrecht , 6th edition 2014, § 38 marginal no. 2 ff. (P. 855).

- ↑ Matthias Herdegen: Völkerrecht , 11th edition 2012, § 27 marginal no. 7 (p. 204).

- ↑ Andreas von Arnauld: Völkerrecht , 2nd edition 2014, § 9 marginal no. 587.

- ^ Friedrichsen: The position of the foreigner in German laws and international treaties since the age of the French Revolution , Diss. Göttingen 1967, p. 19; von Frisch, Das Aliensrecht , 1910, pp. 20 f.

- ^ Günter Renner: Aliens Law in Germany , 1998, § 2 No. 4 (p. 2).

- ↑ Werner Kanein: The Aliens Act , 1966, introduction (p. 3/4).

- ^ Günter Renner: Aliens Law in Germany , 1998, § 2 No. 15 (p. 6).

- ↑ Law on the acquisition and loss of the status of Prussian subject and entry into foreign government services of December 31, 1842, GS p. 15.

- ↑ Law on the admission of newly attracted people of December 31, 1842, GS p. 5. Printed in the collection of sources for the history of German social policy 1867 to 1914 , Section I: From the time when the Empire was founded to the Imperial Social Message (1867-1881) , 7. Volume: Poor law and freedom of movement , 2 half volumes, edited by Christoph Sachße, Florian Tennstedt and Elmar Roeder, Darmstadt 2000, Appendix No. 2.

- ^ Günter Renner: Aliens Law in Germany , 1998, § 2 No. 16 (p. 7).

- ^ Günter Renner: Aliens Law in Germany , 1998, § 2 No. 19-21 (pp. 8-10).

- ↑ Günter Renner: Aliens Law in Germany , 1998, § 4 No. 26 (p. 11).

- ↑ Police Ordinance on the Treatment of Foreigners (Aliens Police Ordinance) of April 27, 1932, PrGS p. 179.

- ^ Günter Renner: Aliens Law in Germany , 1998, § 5 No. 44/45 (pp. 17/18).

- ↑ RGBl. 1938 I p. 1053 .

- ^ Günter Renner: Immigration law in Germany , 1998, § 6 marginal no. 52 (p. 20).

- ↑ BGBl. 1965 I p. 353 .

- ↑ Werner Kanein: The Aliens Act , 1966, § 2 (p. 40).

- ↑ Directive 64/221 / EEC of the Council of February 25, 1964 on the coordination of special provisions for the entry and residence of foreigners, insofar as they are justified on grounds of public order, security or health (OJ 56 of April 4, 1964, Pp. 850-857).

- ↑ Regulation (EEC) No. 1612/68 of the Council of October 15, 1968 on the free movement of workers within the Community (OJ L 257 of October 19, 1968, p. 2).

- ↑ Federal Law Gazette 1969 I p. 927 .

- ^ Günter Renner: Immigration law in Germany , 1998, § 7 marginal no. 59 (pp. 24/25).

- ^ Günter Renner: Immigration law in Germany , 1998, § 7 marginal no. 62 (p. 26).