Adoptive emperor

The adoptive emperorship encompasses a period of the Roman Empire during which succession to the rule was regularly determined by adoption (98-180 AD). According to the reading that was officially widespread at the time, this involved selecting the most suitable candidate as a successor. However, modern research has now put this idealizing view into perspective.

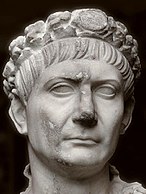

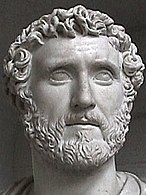

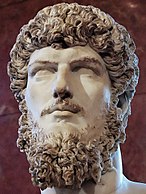

Adoptive emperors in the sense of the current historical term were Nerva , who was not adopted but rather elected by the Senate, Trajan , Hadrian , Antoninus Pius , Mark Aurel and Lucius Verus , none of whom came to rule as the biological sons of their predecessors. In other languages, this imperial era - with reference to Antoninus Pius as the namesake - is sometimes referred to as the Antoninian dynasty , then also with the inclusion of Mark Aurel's son Commodus .

The principate of the emperors from Nerva to Mark Aurel is still often considered the heyday of the Roman Empire and a symbol of good monarchical rule , which is why these emperors (omitting the co-emperor Verus) are also known as "the five good emperors", especially in English-speaking countries become. During her period of rule, Trajan initially saw the phase of the greatest expansion of the Roman Empire, followed by a comparatively relaxed military era of external and internal consolidation, infrastructural expansion and economic prosperity. The end of this era, which in retrospect was transfigured as the “golden age” by authors like Cassius Dio and Herodian, appears in the self-reflections of the “philosopher emperor” Mark Aurel from his last years of reign.

Background: Adoption law in the age of the Roman Republic

Since the Republican era, adoption has been a widespread means among members of the nobility to ensure the continuity of their own sex in this way if there are no biological heirs. The one who was adopted in lieu of his son took over the name, property and clientele of the adoptive father and was legally treated exactly like a biological son. Such an adoption under private law originally took place as an adrogatio before the comitia curiata (curiate meetings) under the supervision of the most important college of priests, the pontifices . In addition to adrogation, in which both adoptive partners were publicly asked ( rogated ) for their consent , there was later the adoption of the child ( adoptio ), which placed the adoptive under the domestic authority ( patria potestas ) of the adoptive father and removed the legal ties to the family of origin.

One of the best-known examples of adoption from the Republican era is that of the younger Scipio , the second son of Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus , the victor in the Third Macedonian-Roman War . After the adoption by Publius Cornelius Scipio , he added the extended gentile name of his father (Aemilius) to the new one and was now called Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus . Later on, Caesar's testamentary adoption of Gaius Octavius, later Augustus , became the basis for the transition from republic to principate .

Adoption for the purpose of succession in principle

Without his own biological sons, Augustus, as the first Roman emperor, had to regulate his own succession by way of adoption. In any case, the principate was formally not hereditary at any time. Because the ruling power was given according to the legal form by the people and the Senate to the respective Princeeps. In practice, however, the efforts of incumbent emperors to make their own sons successors could hardly be countered. But since the son or adopted son of an emperor was legally only his private heir, it was part of a regular succession, the next princeps already during the lifetime of the predecessor of the Senate with the corresponding powers ( tribunicia potestas and imperium proconsulare ) as well as dignities such as the suffix Caesar , the 69 was first awarded, or to furnish princeps iuventutis .

After all of the blood relatives in question had died, Augustus finally adopted his stepson Tiberius and had the appropriate powers given to him. Also Claudius adopted his stepson Nero and did so even though he and Britannicus had a (albeit younger) own son. Nero's childless successor Galba tried in vain to secure his position in the four-emperor year 69 by adopting a younger senator ( Lucius Calpurnius Piso Frugi Licinianus ).

A chance to choose the best?

When the Flavian dynasty ended with Domitian's forcible elimination and the Senate had imposed the abolitio nominis on the emperor, who was last hated by many , there was a renewed interest in the establishment of a suitable principle on the Senate side. Nerva may have been chosen deliberately as a transition candidate. His adoption of Trajan, who was not inconvenient to important senators as future rulers, created a situation in which Trajan and the Senate met in the interest of Nerva's adoption decision, which actually preceded a bitter power struggle, as the selection of the most suitable in terms of the Roman community to propagate. This could serve Trajan as legitimation of his rule; Under these circumstances, the Senate, in turn, was apparently able to introduce its own ideas regarding the selection and properties of an ideal principle.

The historians Tacitus and Pliny the Younger were among the senators who demonstratively represented an image of the ruler that was strongly related to the common good and friendly to the senate . When he had to give a speech of thanks to the emperor for the suffect consulate made possible for him by Trajan in 100 , he expressed the wishful principle of choosing the best:

“Whoever is to rule over all must be chosen from among all. You don't want to put a new master in front of your slaves so that you could be satisfied with an heir according to legal regulations, but you want to give the citizens of Rome a new princeps and emperor. That is why you would act presumptuously and despotic if you did not adopt the one who, according to the unanimous opinion, would have come to power even if you had not adopted him. […] The best Princeps [Nerva] gave you his own name when you adopted it, and the Senate that of Optimus . [...] With what heartfelt joy, divine Nerva, you can now experience that the man you have chosen as the best is really the best and is also called that. "

Tacitus , too, formulated the ideology of the adoptive emperorship in the histories he wrote a few years later , and already put these thoughts into Galba’s mouth:

“If the huge body of the empire could exist without a handlebar and be kept in balance, I would deserve to start the republic again with me. […] Under Tiberius , Gaius and Claudius , we were, so to speak, the inheritance of a single family. From now on it should be a substitute for freedom that we begin to be chosen emperors; and since the Julier and Claudier house is now extinct, adoption will always choose the best. Because to be begotten by principes is a coincidence, and then no further questions are asked about the value; in the case of adoption, however, the judgment is free, and if you want to choose someone, the general mood already gives you a clue. […] With us, as with the peoples ruled by kings, there is no specific ruling house and otherwise only slaves. "

This notion, conveyed by the sources, that a pioneering, new program of the invention of the emperors was born in the Roman Empire, which had become authoritative or even binding for the subsequent adoptive emperors, was for a long time adopted quite uncritically. But it is very much relativized in recent research. A stoically oriented opposition among the senators may well have favored the choice of the best even in the time of Nero and the Flavians, with the dynastic principle removed; However, according to Jörg Fündling , the current research consensus says that a “stoic electoral empire” never existed in the political reality of the imperial era. The very fact that the emperors initially adopted their designated successors under private law, an act that was of crucial importance, but in which the Senate was not involved, suggests that in truth they did not deviate from dynastic thinking, and that alone for practical reasons it probably couldn't. In addition, the supposedly ideal candidates chosen by the emperors were often also their closest male relatives - Hadrian was Trajan's great-nephew, Marcus Aurelius was Antoninus Pius' nephew by marriage. The only new thing was that the emperors from Trajan onwards, with the help of the Senate, ideologically exaggerated the not at all innovative procedure of choosing a successor to “choose the best”. This did not change the balance of power.

Karl Strobel , who examines Pliny’s acceptance speech to see whether it was designed as a prince’s mirror to influence Trajan or whether it only contained what the emperor wanted to hear from Pliny, comes to the conclusion: “Pliny spreads before us in the frame of the genre rules from which he could expect that one wanted to hear it like this or something similar and that Traian and the authoritative men around him would like it. [...] In the expansion of Traian's entire strategy of legitimation for his rule, Pliny becomes the emperor's propagandist. ”In any case, there was no unified ideology of the Senate, as the exponent of which Pliny could be considered. The senatorial class consisted of different groupings, each with their own interests and with different political-pragmatic priorities, but who, if they did not want to fall out of favor, had to subordinate themselves to the requirements of the senators who belonged to the emperor's immediate vicinity. "With very few exceptions, the members of the Senate have been opportunists in the history of this body and followers who are concerned about their well-being," said Strobel.

Women as a binder in dynastic power politics

From the perspective of the ruling adoptive emperors, in the absence of a biological heir for succession planning, the problem of a sufficiently clear legitimation of the intended heirs arose. In addition to adoption, female relatives were also used for the purpose of targeted marriage. Thus, the engagement of a young relatives could already be seen as a signal that the successor -in-law indicated that without this through adoption and establishment as Caesar had already officially as a future emperor nominated. The latter was often delayed as long as possible so that the coming man did not already partially withdraw the public's attention from the incumbent emperor and thereby weaken the latter's exercise of power. This constellation can be based on the transition of the imperial dignity from Trajan to Hadrian, which did not leave the impression of "an impeccable, 'clean' accession to power" because Trajan postponed the appropriate time for the adoption of Hadrian "in a sufficiently official framework" for too long .

The “role of the women of the imperial family as a central element of dynastic construction” has recently been specifically emphasized by Karl Strobel. Hadrian set special accents in this regard by not only divinising his mother-in-law Matidia , Trajan's niece , but also by building a monumental temple with a 17-meter-high column front for her on the Field of Mars .

“Aedicules, niches framed with columns and gables, were attached to the magnificent temple, the shape of which has only been handed down through the coin images. The building and its forecourt were flanked by two-storey basilicas, one of which was dedicated to the Diva Marciana, the mother of Matidia, the other to the deceased herself. "

This was the first temple ever built for a woman in Rome. Only for the wife of Antoninus Pius, Faustina the Elder , was such an exception again made after her death in 141 with a temple in the Roman Forum . As the mother of Faustina the Younger , who had released Antoninus Pius from her engagement to Lucius Verus and betrothed Marcus Aurelius - the wedding took place in 145 - she was suitable as Trajan's great-granddaughter and Matidia's granddaughter, the blood-like legitimation of the last in the series the adoptive emperor to ensure.

Permanent priority of the biological heir

That the supposed selection of the best through adoption had not become the new, binding guideline in the Roman Empire, became apparent when Marcus Aurelius and Commodus were able to make a biological son as his successor for the first time since the times of the Flavian emperors, despite his being a problematic nature also did: Already at the age of 5 years Commodus was raised to Caesar by his father . Strobel sums it up: “The adoption did not create a new type of empire, but only practiced the solution on the level of monarchical rule that was taken for granted in Roman thought and in the Roman family structure when no biological son was available for the succession. "

After the murder of Commodus, Septimius Severus claimed a (fictitious) adoption for himself by Marcus Aurelius in 193. However, this remained without a successor, as Severus had two biological sons, which is why we no longer speak of adoptive emperors here. Nonetheless, the Severers followed the Antonines in their naming. so the emperors Caracalla and Elagabal carried the official names Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus and Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, respectively . The extremely bad reputation of these two rulers, however, discredited the name Antoninus in such a way that Elagabal's successor Severus Alexander called himself Marcus Aurelius , but not Antoninus . The rulers who succeeded the adoptive emperors also strove to found their own dynasty if they were not already in a dynastic row. But even in late antiquity (4th – 6th centuries), adoption played an important role for childless emperors as a sign of the designation of the presumptive successor. The events surrounding Constantine I 's elevation as emperor in 306 made it clear that the dynastic principle - although still irrelevant under constitutional law - almost always played a decisive role in cases of doubt: since Nero , no emperor's son has ever been bloodlessly excluded from the succession , this was only possible through violence.

Historical classification of the adoptive emperorship

The era of the adoptive empire, sometimes also referred to as humanitarian empire in the scientific literature, taking into account other characteristics , is based on the one hand in the fact that from Nerva to Antoninus Pius none of the rulers had a biological son, based on the one in Panegyricus Pliny the Younger The programmatic generalization and ideological exaggeration expressed, however, according to Karl Christ, also on the historical accompanying circumstance “that a severe political crisis forced a new stylization of the Principate.” In view of the bitter reckoning of many senators with the Principate Domitian, the distance from this predecessor is for Nerva and Trajan have been fundamental. The ideologeme of the adoption of the best thus served to secure one's own power: “Even if the function of the principate ideology has always been particularly important at the beginning of every new principate, it gains a meaning here that is reminiscent of that of the ideologems of the year 27 BC. The authoritarian arrogance of a Domitian was opposed to key concepts of a civilitas aimed primarily at the common good , such as modestia (moderation), moderatio (prudence), mansuetudo (gentleness) and humanitas (humanity).

The time of the adoptive emperors was also a heyday of the second sophistry , first so called by Flavius Philostratos , whose representatives in the cultural metropolises of the eastern half of the Roman Empire, especially in Athens , Ephesus ; Pergamum and Smyrna , a return to the Greek culture of the classical period . The adoptive emperors were also open to this spiritual trend, especially with the arrival of the philhellenic Hadrian, who took an active part in the cultural, religious and philosophical traditions of the Greeks. The response was mutual, as Alfred Heuss sought to show with reference to the adoptive emperors: “Spiritual Greece gave them its approval from the mouths of the leading figures and made itself the spokesman for the public of the empire and thus of the Roman Senate circles. This empire deserves the name of an 'enlightened' and 'humane' monarchy that has been given to it in modern research. "

Well-known representatives of the second sophistry who were in contact with adoptive emperors include, above all, Dion of Prusa and Aelius Aristides . The eulogy given by the latter to Antoninus Pius on the contemporary Roman Empire, whose freedom of movement, internal security, traffic infrastructure and civilized unity he extolled among other things, has its modern equivalent in the judgment of Edward Gibbons : “If someone should be asked, the period of world history to indicate during which the situation of the human race was the best and happiest, he would without hesitation name the one which passed between the death of Domitian and the accession of Commodus. "

From the point of view of contemporaries and ancient posterity, the government of Antoninus Pius in particular was characterized by external stability and inner calm (according to Aelius Aristides in his speech on Rome ) and was considered a glorious epoch of peace and prosperity. From the point of view of recent research, some positive exaggerations of the humanitarian adoptive empire should be taken back, according to Oliver Schipp, and attributed to Roman pragmatism and utilitarianism; but subject to some points of criticism and problems, one can speak of a golden age in the end. Other researchers, however, deny this and emphasize the structural instability of imperial rule, which was only ideologically veiled.

In the late phase of the adoptive empire, the so-called imperial crisis of the 3rd century was already casting its shadow. Mark Aurel's reign was already marked by looming external and internal problems, such as the growing threat to the north-eastern borders from Germanic warriors and inflation associated with the deterioration of coins. The assumption of power by Mark Aurel's son Commodus ended, as already mentioned, the series of adoptions due to the lack of biological sons and was viewed by contemporary Cassius Dio ( Roman history 72,36,4) as a transition from a “golden age” to a “rust and iron ”. The murder of Commodus at the end of 192 was followed by the bloody power struggles of the second year of the four emperors , in which Septimius Severus finally prevailed. Under the Severi the importance of the military element in the ascension of rulers grew, which was to become even more important for the soldier emperors during the imperial crisis of the 3rd century, while the senate continued to lose importance for the establishment of the imperial position.

Rulers' gallery

literature

- AK Bowman et al. a. (Ed.): The Cambridge Ancient History . Vol. 11 Cambridge 2000.

- Albino Garzetti: From Tiberius to the Antonines . London 1974.

- Michael Grant : The Antonines. The Roman Empire in Transition . Routledge, London 1994, ISBN 0-415-10754-7 (very brief representation).

- Johannes Pasquali: The adoptive emperors. The Roman Empire at the height of its power (98–180 AD) . Projektverlag, Bochum 2011, ISBN 978-3-89733-229-4 (A very problematic representation that takes on the self-portrayal of the adoptive emperors largely uncritically.)

- Oliver Schipp: The adoptive emperors. Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antonius Pius, Marc Aurel, Lucius Verus and Commodus. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2011, ISBN 978-3-534-21724-3 . (Schipp's book has been accused of significant deficiencies, see for example the specialist review in the viewing points )

- Colin Wells: The Roman Empire . DTV, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-423-04405-5 , pp. 231-304.

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ This is the name of the corresponding article in the English language Wikipedia Nerva-Antonine dynasty and in the French language Antonins (Rome) . The problem is this designation, however, that the emperors of the dynasty of Severus (193-235) had the name Antoninus, as they claimed a fictitious kinship with Commodus.

- ↑ Oliver Schipp: The adoptive emperor. Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antonius Pius, Marc Aurel, Lucius Verus and Commodus. Darmstadt 2011, p. 14 f.

- ↑ Schipp 2011, p. 14, citing in this context the so-called lex de imperio Vespasiani ( Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum Vol. VI, No. 930)

- ↑ See Werner Eck : An Emperor is Made. Senatorial Politics and Trajan's Adoption by Nerva in 97 . In: Gillian Clark, Tessa Rajak (eds.): Philosophy and Power in the Graeco-Roman World . Oxford 2002, p. 211 ff.

- ↑ Quoted from Oliver Schipp: Die Adoptivkaiser. Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antonius Pius, Marc Aurel, Lucius Verus and Commodus. Darmstadt 2011, p. 17.

- ^ Tacitus, Histories 1:16

- ↑ Jörg Fündling: Commentary on Hadriani's Vita from the Historia Augusta . 2 volumes, Bonn 2006, vol. 4.1, p. 394 f.

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Regensburg 2010, p. 455.

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Regensburg 2010, p. 456. In an appendix to his Trajan biography, Strobel deals with further aspects and positions of recent research on Pliny 's Panegyricus. (Ibid, pp. 454-460)

- ↑ Jörg Fündling: Commentary on Hadriani's Vita from the Historia Augusta . 2 volumes, Bonn 2006, Vol. 4.1, pp. 383/386.

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Regensburg 2010, p. 410. See also Peter Weiß : The exemplary imperial marriage. Two Senate resolutions on the death of the older and younger Faustina, new paradigms and the formation of the “Antonine” principle. In: Chiron 38, 2008, pp. 1-45.

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Regensburg 2010, p. 409.

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Regensburg 2010, p. 409 f.

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Regensburg 2010, p. 410.

- ↑ Henning Börm : Born to be emperor. The principle of succession and the Roman Monarchy . In: Johannes Wienand (Ed.): Contested Monarchy . Oxford 2015, p. 239 ff.

- ↑ Karl Christ: History of the Roman Empire. From Augustus to Constantine. 5th edition, Munich 2005, p. 287 f. (The principate was established by Augustus in 27 BC .)

- ↑ Karl Christ: History of the Roman Empire. From Augustus to Constantine. 5th edition, Munich 2005, p. 289.

- ↑ Oliver Schipp: The adoptive emperor. Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antonius Pius, Marc Aurel, Lucius Verus and Commodus. Darmstadt 2011, p. 120.

- ^ Alfred Heuss: Roman history. 4th edition, Braunschweig 1976, p. 344.

- ^ Edward Gibbon: The History of the Decline and the Fall of the Roman Empire. Quoted from Schipp 2011, p. 127.

- ↑ Oliver Schipp: The adoptive emperor. Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antonius Pius, Marc Aurel, Lucius Verus and Commodus. Darmstadt 2011, p. 128.

- ↑ See for example Ulrich Gotter : Penelope's Web, or: How to become a bad Emperor post mortem . In: Henning Börm (Ed.): Antimonarchic Discourse in Antiquity . Stuttgart 2015, pp. 215-233.