Labor economics

The labor economics is a branch of economics that result from an economic perspective, the functioning of labor markets is concerned. The central object of investigation is the supply and demand for people as an essential factor of production . For this purpose, the focus of the discipline is, for example, on the factors and mechanisms that influence the decision to take up work, the choice of individual work, the level of wages and the level of unemployment.

The neoclassical theory

In the standard model of neoclassical theory , the labor market follows the same rules as a classic goods market and can also be characterized by supply and demand curves. The course of the curves depends on the individual preferences of the job providers (households) and the job seekers (companies), whereby the following assumptions are made in the simplest model:

- There are no barriers to entry or other restrictions of competition on the labor market.

- The labor providers are homogeneous : they do not differ in terms of their productivity and are therefore completely substitutable (interchangeable). In addition, there is no discrimination whatsoever .

- The job market is transparent : all actors (job providers and job seekers) always have complete information at their disposal, so they know about the current and future market situation at all times. This includes, for example, that both households and companies are aware of the market clearing wage for a position.

- The adaptation processes are infinitely fast and are not influenced by rigidity or friction. For example, supply and demand react immediately to price changes.

- The job providers are completely mobile (and ready for mobility), so that spatial factors have no relevance for their choice of offer.

- There are no transaction costs . In particular, this also excludes costs for obtaining information (for example about vacancies).

The job offer

The job provider basically has a multitude of options at his disposal for dividing his time budget. The conceivable activities can be subdivided into different "time (use) groups" to make them easier to understand, including, for example, paid working time, housework time, regeneration time and leisure time. For the sake of simplicity, a distinction is usually only made between work and leisure as alternatives, the term “work” standing for gainful employment and “leisure” for all other activities.

An actor chooses the time allocation that brings him the greatest possible benefit (principle of benefit maximization ).

Determination of the individual job offer

An individual actor always uses his (freely divisible) time budget either for work or for leisure . The personal freedom to divide one's time for different purposes is therefore subject to time restrictions

-

.

( : Total time budget in hours ,: working time in hours ,: leisure time in hours)

In addition to this time restriction, there is a second restriction, the budget restriction . She can be classified as

-

( : Consumer spending in euros ,: wages in euros / hour ,: non-wage income in euros)

(for the sake of clarity, all prices have been normalized to 1 so that nominal and real income are identical). Since only one period is considered and positive marginal utility of income is assumed, the budget equation of a utility-maximizing job provider applies (the entire monetary income is spent). The resulting budget line shows the slope . As the utility maximizer, the job provider thus solves the maximization problem

under the constraint , where quasi-concave and continuously differentiable. Those leisure-consumption combinations that create the same level of benefit form a (strictly monotonically falling and convex) indifference curve . The classic properties apply to these, in particular the benefit level of income-leisure combinations increases with the distance of the respective curve from the origin. With a maximum achievable income of , the point in the diagram marks the maximum useful work input. The slope of the indifference curve corresponds there to that of the budget line; Identical to this, it can also be formulated that the marginal utility ratio of leisure and consumption corresponds to wages . In other words: “The 'subjective' exchange ratio between the two goods is equal to the 'objective' exchange ratio, which is indicated by the level of the wage rate.” Thus, in point there is the household balance.

For the neoclassical standard model as a whole, the preceding considerations imply the existence of individual reservation wages, which denotes the wage rate that is at least required to motivate people to take up a (further) hour of work. The reservation wage thus corresponds precisely to the marginal rate of substitution at the lowest point of the budget line; In the above model, it is solely dependent on the specific form of the utility function and the level of non-wage income , whereby it is positively dependent on this (provided that leisure time is a normal good).

Reaction to wage and income changes

There are two possible reactions for an employee to a wage increase. On the one hand, he can expand his job offer, i.e. work more and forego part of his free time. In economic terms, this can be justified by the opportunity costs of leisure time: if the offered wage increases, it becomes relatively more expensive not to work. This effect is known as the substitution effect because the job provider substitutes (replaces) leisure time with work. A second conceivable reaction is the restriction of the labor supply - the wage increase gives the worker the opportunity to turn to other goods (vacation, family, etc.). This is the income effect . The income effect of a wage increase differs from an income effect on a classic goods market in that the monetary income of an actor changes (by definition), whereas this is not the case with corresponding price changes in other markets.

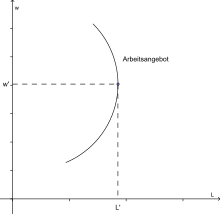

For this reason, the income effect can be broken down into a “normal” or “pure” income effect and an “additional” income effect (endowment income effect) . The former is always negative with regard to a wage increase based on the assumption that leisure time is normal , which is easy to see if one imagines that instead of wage income, non-wage income would be increased. The sign of the latter, on the other hand, is not determined, so that an increase in the wage rate can theoretically also lead to a reduction in working hours, although work in itself is a normal good. In fact, it can be assumed that the strength of the income effect is closely related to the level of income that the actor has received up to now: if the wage increases, the labor supply rises initially, but then decreases again from a real wage . For supply curves, this sometimes implies semicircular, backward-curved courses (backward-bending labor supply curve). In the literature, this subdivision of the income effect is usually not made and one simply speaks of an overall effect that is indefinite in its direction of action.

The effect of a change in wages on labor can be quantified using the (Marshall's) elasticity of the labor supply . It is defined as

and indicates the percentage change in working hours that a one percent wage change entails. Dominates the substitution effect, applies for even a preponderance of income effect implies accordingly .

Extensions

In the literature, many extensions of the classic model framework are suggested. A modelable inadequacy of the basic model is, for example, that due to the dichotomous "time-use groups", differences in the preference and utility structures of activities in the area of non-wage income are not taken into account. This includes, in particular, the fact that households spend a considerable part of their time on productive activities (think of cooking [in a substitute relationship for going to a restaurant] or sleeping [as a condition for successful gainful employment]). In this light, Gary Becker (1965) tries to bring the model closer to reality by introducing a production component in the utility maximization problem. The various activities of a household can in turn influence the decision making process positively or negatively. Another part of the literature tries to include the role of family structures in the model. For example, one can aggregate individual budget restrictions and / or aggregate the individual benefits of the family members so that only the overall benefit is maximized while limiting the overall budget. For example, Pierre-André Chiappori suggested in several papers a collective model in which the household members maximize their benefit individually, but this also depends on the individual benefit of other household members, so that there is effectively a certain distribution of individual risks.

Another group of expansion approaches starts with the linearity of the budget constraint. In reality, this will generally not be the case because, for example, progressively levied taxes endogenous to the budget constraint in such a way that the realizable budget amount must now be treated as a function of working time.

The demand for labor

The demand for labor follows the maxim of profit maximization . As with the theory of labor supply, this basic assumption already disregards many actors, including, for example, non-profit organizations or the state. Work is one of the production factors for a company and is combined with other factors such as capital in such a way that the highest possible profit is achieved. Labor has a positive marginal product; H. an additional unit of labor is always suitable to increase the output of the labor consumer. Whether a worker is hired at all depends on the one hand on the resulting wage costs, on the other hand on the costs of other production factors (e.g. capital) and other specific individual factors that determine the company's sales (e.g. the productivity of an employee).

Determination of individual labor demand in a short period of time

As a rule, the input factors capital and labor are regarded as relevant for the labor demand decision . Since the capital stock and other influencing factors such as company size are usually assumed to be constant in the short term, labor is the only variable production factor in the short term. The general short-term production function follows from this , for which the following properties are assumed to apply:

The job offer from the point of view of the individual entrepreneur is perfectly inelastic due to the assumption of complete competition in the sales market (the individual actor has no influence on the wage level).

For the determination of the mechanisms of action of the demand for labor, it is crucial which assumptions are made about the labor market and the sales market for the goods produced. First of all, the following assumes a company that operates in a competitive labor and goods market environment (in the following section “Forms of incomplete competition” these assumptions are then gradually abandoned). In concrete terms, this means that, on the one hand, the wages do not depend on the company's decision to hire, and on the other hand, the price of goods cannot be influenced by how much the individual actor produces. A company that produces in such an environment then follows the profit function, for example

-

( : Profit : capital [here constant] : labor, : price of a goods unit : sales volume, : wage / hour : user cost of capital, : taxes / duties, etc.)

For a maximum it is then necessary:

- that is the product of the selling price and the physical marginal product of labor - is here as value marginal product of labor ( English value of the marginal product called). Since the physical marginal product by definition corresponds to the amount of production that would produce an additional unit of labor, the marginal value product of labor describes the turnover that the company could achieve by using an additional unit of work. It follows from the equation that the marginal value product of labor must optimally correspond to wages . If it is higher, new workers bring an increase in profits, if it is lower, a new employment relationship would obviously no longer be profitable and the company would accordingly hire or fire workers until the marginal product of the workforce equals the workforce's wages. Accordingly, the curve of the marginal value product on competitive markets - as shown in the figure - is identical to the labor demand curve due to the exogenous nature of the wage.

If one looks at the effects of a wage increase on the work demanded, the effect is immediately apparent from the assumptions made - the demand for work falls. In the case of labor demand, unlike in the case of labor supply, there are no two contrary quantitative effects.

Monopoly structures

If one gives up the assumption of complete competition on the goods market, the price is no longer fixed; rather, the company now has a direct influence on the market price through the quantity of goods it produces. This is a form of monopoly power, so new (and still ). The following applies to the profit function

- ,

therefore necessary at the maximum (and also sufficient)

An equivalent expression for this is better suited for considering the differences from the perfectly competitive model:

-

( : Elasticity of demand on the sales market)

The above condition for profit-maximizing wages in a monopsonistic labor market is the functional equivalent to the marginal value product in the case of complete competition; it differs from this only in the elasticity factor . In fact, the resulting term for is a generalized form of marginal value product in perfect competition, and the term is generally referred to as marginal revenue product (MRP). A generalization is given because in a competitive market and is true, so that the marginal revenue product can be converted directly into its special form of the marginal value product.

The neoclassical standard model for cases of incomplete competition also implies a lower demand for labor than in the competitive case. This is because, in the case of incomplete competition, production always takes place on the elastic part of the demand curve - since the elasticity of demand is then always negative, the marginal revenue product is also always lower than the marginal value product. The intuitive explanation for this fact is that hiring an additional worker leads to an increase in output. However, if the company has pricing power in the sales market, the expansion of production according to the laws of supply and demand will lower the sales price ( falls in ). As a result, hiring additional workers is no longer that lucrative.

Monopsonistic structures

A much-noticed special case of the non-competitive labor market environment is the monopsony (also: “demand monopoly”), in which there is only one demand for labor. While in perfect competition the company acts as a “price taker” with regard to the wage rate - i.e. it is confronted at the individual level with a horizontal labor supply curve, in which every marginal wage rate decrease below the market wage would result in the loss of the workforce - with forms of the monopsonistic competition has a direct influence on the wages forming in the market. The reward is therefore a function of the newly requested amount of work: . It also applies here that there is a rising labor supply curve.

Analogous to the case above, the monopsony model now applies to the gain function

and at the maximum necessary (and also sufficient)

The marginal value product of labor must therefore correspond precisely to the marginal costs of labor. In comparison to the competitive case, important statements can be made from this for the wage rate . Because according to the prerequisites, the wages in the environment of a monopsonic or monopsonistic competition are obviously lower than with complete competition.

This is a general result. Intuitively, the explanation is that when the labor market is fully competitive, the labor demand decision does not affect market wages; but if the company gains market power, as in the monopsony case, a higher demand from the monopsonyist increases the price of the goods in accordance with the laws of supply and demand, which in the case of work consists of wages. This effect, in turn, has a negative effect on the company's profits, which is why the demand for labor of a monopsonist also lags behind that of an actor with full competition. But since the wage rate rises in the demand for labor, the monopsonyist not only hires fewer workers than would be the case in perfect competition, but also pays the workforce even less.

A social planner can generally cope with the negative effects of a monopsy on employment and wages by introducing a minimum wage . As can be seen graphically in the figure, a minimum wage of leads to a change in the marginal cost structure. In the area in which the factor marginal costs are above the marginal value product or marginal revenue product, a minimum wage that is above the monopsony wage but below the maximum wage rate given by the intersection of the original marginal cost curve and the curve of the marginal product (in the diagram:) sets the marginal costs of work exogenously to the level of the minimum wage (as long as the minimum wage is not exactly above the marginal revenue product - but there is no longer any demand for work). The minimum wage thus approximates the imperfect market result to the result of full competition desirable for labor providers. If you set the minimum wage exactly equal to the competitive wage, all negative effects of the monopsy on employment and wages are neutralized. Any minimum wage below the monopsy, however, would not be binding and therefore ineffective; every minimum wage above would lead to a decline in labor demand (and thus unemployment) compared to the competitive equilibrium.

Determination of individual labor demand in the long term

While the capital stock can be viewed as a fixed (as it is exogenous) variable in the short term, this is usually not the case in the long term. This is because, in larger time horizons, there is the possibility that labor and capital are to a limited extent in a substitute relationship. In reality it can be observed that in the course of technology processes certain workplaces are replaced by robots.

In the long term, therefore, the new production function applies first and both the profit-maximum amount of labor and the profit-maximum amount of capital must be maximized. Therefore - assuming particularly simple and appropriately constructed function processes - in a situation with a competitive goods market environment (the general case is not taken into account at this point), in addition to the already known condition for the maximum profit

- ,

In addition, the condition for the maximum profitable capital must be met:

In summary:

The condition states that a profit-maximizing company modifies its labor and capital input until the marginal costs that would arise in the production of another unit of goods using labor are identical to those that arise in production using capital.

Transfer to the macro level

The supply and demand curves imply an equilibrium at their intersection; for wage rates below the equilibrium wage there is a demand surplus, for those above a supply surplus.

The described static view enables a very simple transfer of this intrinsically microeconomic analysis model into a macroeconomic dimension, in that market events are viewed as the interaction of a representative job provider and a representative job seeker. This idea is reflected in a corresponding market diagram, which is shown on the right: the higher the wage rate, the lower the work demanded and the higher the work offered.

If one sees how this is the core of the concept of the representative actor, the macroeconomic supply or the macroeconomic demand as an aggregation of individual labor demand and labor demand curves, it can be seen that the mere horizontal aggregation of labor demand curves leads to incorrect results. This is not only based on the fact that labor demand curves can in principle only be aggregated horizontally if the sales price is completely fixed (i.e. there is full competition on the sales market). Rather, the procedure ignores the fact that the fact that each individual company cannot influence the market price of the goods to be sold by changing its goods production does not also mean that the sale price would remain constant even if each company changes its output. In the aggregated demand curve, it must therefore be taken into account that, for example, an increase in labor input via an increase in output will lead to a reduction in the selling price, which in turn creates an incentive to reduce labor input. As a consequence, the mechanism described leads to the fact that, regardless of the market structure, the aggregated demand will have a steeper downward trend than a curve that has arisen through horizontal aggregation.

The equilibrium indicated by the intersection of the supply and demand curves is the only stable market condition. For every wage there would be unemployed labor providers who would be willing to work for a wage , so that a mutual undercutting competition would be set in motion on the supplier side, at the end of which the equilibrium wage is again. Similarly, for every wage there would be companies who want to ask for additional labor and who are willing to pay for it, so that an overbid competition would start. At the same time, the equilibrium is also the only Pareto-optimal market condition: for every (wage) condition , as can be seen from a contract curve, there is a reform possibility that puts at least one actor in a better position without making any other - regardless of household or company - worse put.

criticism

The assumptions of the static (neoclassical) standard model differ in many respects from the observations in reality. For example, it cannot take into account the fact that employees actually rarely have the opportunity to make completely independent decisions on the number of hours worked. In addition, the standard model cannot explain the occurrence of wage differentials. Likewise, inheritance structures on the employer and employee side are not adequately taken into account. Although it is possible to integrate different degrees of monopoly or monopsony power into the model with the help of different elasticity parameters, the aggregation required for their estimation inevitably leads to a loss of information.

Efficiency wage theories

Addiction Theory and Matching Technology

The micro level - workers as seekers

One of the basic assumptions of the neoclassical basic model of the labor market is that all market actors have perfect information. For example, they know about available job offers as well as the associated requirements and their respective salary. This premise, which obviously runs counter to perceived reality, has been abandoned in the addiction theory of the labor market, which has been in use especially since the 1970s . Search theory models of the labor market focus on the job search preceding an employment - since job providers do not have perfect information, this search process is itself a productive activity and job providers are constantly faced with the question of what part of their time budget they spend on their actual time in a frictional market environment Activity and what they should spend looking for a (more productive) job. In doing so, job providers and job seekers both endeavor to fill existing vacancies (i.e. vacancies); the search process already described must first lead to a meeting of two actors; At the end there is finally a match (i.e. a successful agreement between the parties) with a certain “contract probability”.

While the first search models - in particular that of George J. Stigler (1962), which is widely regarded as the origin of the search theory of the labor market - still a two-period view prevailed, in which the job providers the optimal number of their steps (i.e. the contacts made ) ex ante, then obtain the respective wage offers for the randomly selected vacancies, compare them with each other and finally bring about the highest profitable potential match, later models are based on sequential processes (McCall 1970, Mortensen 1970). In the following, the basic principle of addiction theory is described using a simple model.

Basic model (Franz 2006)

The model outlined below is based on the idea that the seeker visits a company in each period and obtains a wage offer from it. However, until he is in direct contact with the company, he does not know how high it would be - if he even received one (the probability is , see next paragraph). Rather, the wage level follows a density function that does not change over time and the individual offers are distributed independently and identically ( iid ). After all, after every offer (the wage is the only characteristic of a job) , the seeker has to decide whether or not to accept the job. If he does not accept it, he not only waives the income offered, but also has to accept search costs in the next period; if he accepts the offer, however, he misses the higher income that would be offered to him in the following periods.

In summary, the basic assumptions are in detail:

- Employment providers are homogeneous, but are confronted with different wage offers;

- Employment providers know the distribution of wages, but do not know which company is offering which wages;

- Employment providers prefer high over low wages, aiming to maximize their (discounted) lifetime income;

- every contact with a company causes search costs.

It is initially assumed that the probability that a job seeker will be offered a job at all is. This probability differs from seeker to seeker - personality, qualifications or other individual factors have a decisive influence on its value. In addition, the wage rate by which a job is characterized has a negative effect ; the higher the wage offered, the more employers will seek the job and the less the individual will have a chance of receiving an offer. So be a vector of the individual factors and the offered wage, then applies . We also assume that the probability that the searcher will accept a job offer is. is in turn dependent on the individual reservation wage and also on personal characteristics (represented by ), so that .

The probability of accepting the offer is then

where one arrives at this formula intuitively by checking for each wage rate above the reservation wage the probability of receiving a corresponding offer and then weighting this probability with the probability that a company contacted will offer such a wage at all. it describes the probability of receiving a specific wage rate ; the probability of accepting an offer is therefore precisely the sum of the probabilities of accepting a specific offer, in relation to every offer whose wage offered is at least as high as the seeker's reservation wage.

This is the expected wage of an offer accepted in the next period

A strategy in which the discounted expected value of the income resulting from the offer corresponds to the expected return from continuing the search is obviously search-optimal. First you define the expected value of the reservation wage. This simply corresponds to the discounted sum of all wage payments in this amount over the entire period of time, i.e.

according to the laws of calculation on the geometric series . In order to determine the amount of the expected payoff that would result if the offer was rejected, it is first broken down according to the respective search steps or periods. The discounted value of the step immediately following the rejection is then

- ,

where , for example, can stand for benefits from unemployment insurance and corresponds to the search costs that the actor incurs by obtaining a new offer. This may include direct costs such as travel or the like, but in particular also opportunity costs that arise because the actor is inhibited in his other activities.

Taking into account the fact that the seeker is still likely to be unemployed at the beginning of the following period and taking into account the present value of future wage replacement income and search costs below the nominal value, the same applies to the expected income in the following period

In total (i.e. for all subsequent periods) this leads to an expected payoff of

However, according to the above condition, this must now be identical to the sum of the discounted reservation wages, which after a few conversions

leads.

interpretation

Some important findings for the search behavior of job providers can be derived from the model results of the model. The reservation wage depends on the discount rate, the likelihood of a job offer, the likelihood of accepting a job and the expected wage. Clear statements about the effects of these variables can be made, for example, with regard to the (conditional) expected value of the wage rate. The higher this is, the higher the individual reservation wages of the searcher will be, because the continuation of the search is then more worthwhile. The amount of the allowance in the case of unemployment (unemployment benefit or the like) also has a positive effect on the reservation wage, because this reduces the costs of a further search step. As long as the direct net income from the next search step ( i.e. unemployment benefits minus the direct search costs) is not already positive and also exceeds the expected wage , a higher discount rate will continue to have a negative effect on the eligible wage . Since a higher one indicates a higher present preference, this result appears reasonable, since the seeker thus values the previous income higher than any higher future income. With the same restriction, however, the effect of is positive with regard to the reservation wage - the higher the probability of accepting a position, the higher, ceteris paribus, the wage that one expects from it must be.

The addiction theory model also makes it clear what the length of unemployment can depend on. Obviously, the length of the average search time (up to employment) will correlate positively with the reservation wage. A high unemployment benefit and a low present preference can increase the duration of unemployment, as can a high expected wage rate. In times when there are shocks to the demand for labor (for example in the event of recessions or the like), this can mean that labor providers do not take into account the changed economic situation or do not take sufficient account of the changed economic situation when forming their wage claims by shifting the density function (left) do not recognize it as such, but only assume when viewing a low offer that you are at an outer point of the previous density function, i.e. that you have only accidentally received a particularly unfavorable offer (see figure). This further extends the search process (and thus the duration of unemployment).

Evaluation and extensions

An obvious shortcoming of the model presented is that the seekers all (want to) move from a state of unemployment to a state of employment. The easiest way to circumvent this exclusion of “turnovers” is to limit the period of employment exogenously, for example by introducing a “layoff parameter” which, following a certain distribution, terminates jobs (see for example Wright 1987). The more fundamental extension approach is based on explicitly modeling the so-called “on-the-job” search. Starting with the model by Kenneth Burdett (1978), these models have also been used time and again as the theoretical foundation for several empirical findings on search behavior, including the fact that older employees are usually associated with a lower probability of leaving.

Another problem with the above model is that it assumes that the searchers are familiar with the distribution function . Part of the literature has therefore started to include learning effects about the distribution function in the model. Michael Rothschild (1974) assumed for his version of the search model (which, however, was not related to the labor market but to a goods market; the problem is analogous), for example, that the searcher assumes a fixed density function, in which he initially starts from a certain price that he wants to achieve, but revises his asking price after a certain frequency of not reaching this price. This should also take into account the observation that individual reservation wages typically fall with the duration of previous unemployment, which the standard models cannot explain (practical implications of the continuous revision process of the distribution functions can also be found in Burdett / Vishwanath 1988)

The basic assumption that only the wage level is relevant for the acceptance of a job offer can be conceptually modified in such a way that instead of the wage the benefit arising from the job is raised as the criterion relevant to the decision; In a corresponding utility function, for example, not only the wage level, but also the working hours.

In essence, addiction theory models of this kind are supply-side theories - how the demand for labor is composed or how wages develop in reality, they are unable to adequately explain.

A newer and more widely used class of search models randomizes the search and hiring process. Following the original model by Christopher Pissarides (1985), the probability of recruitment is modeled using a matching function - conceptually based on Peter Diamond (1982); the wage in turn is then determined on the basis of a negotiation game. These matching processes, which are central in the field of labor market research, are the subject of the following section in detail.

A macro level - matching and the randomized search process

The modeling of interactions on the labor market by means of a matching function has the primary advantage of being able to model frictions in a simple way and without the need for a general revision of the theoretical basis of the model. Frictions can be of various types: shocks on important macroeconomic parameters of the labor market, such as the number of job seekers, can be taken into account, as can shocks on behavioral parameters of the job providers (e.g. a higher search intensity). The following section outlines the simplest form of the matching function. The presentation of the basic model follows Pissarides 2000 and Economic Sciences Prize Committee of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 2010.

Basics and Beveridge Curve

Let the number of employable people, the proportion of employable persons who are actively looking for a job, and the proportion of employable persons for whom an open position is available. Then the number of job seekers is even and the number of vacancies . A matching function is defined

- ;

where is the number of new hires. For the further calculations it is also assumed that both of its arguments increase monotonously and that it is concave and homogeneous of degree one (constant returns to scale).

The ratio of vacancies to the number of job seekers is denoted by and it applies accordingly - this ratio of vacancies to unemployed is referred to in the following with Pissarides as “market tension”. Furthermore, one defines a vacancy probability . Its connection to the matching function is intuitively revealed by the fact that the product of the probability of filling a position and the number of vacancies should correspond to the number of new hires, i.e. that means . Change provides the definition of :

(taking advantage of the homogeneity property).

If you look at a certain time interval, the probability that an unemployed person will find a new job is . The average duration of unemployment just corresponds to the reciprocal value . The average duration of unemployment is indefinitely dependent on market tension. From the supplier's point of view, a high means a higher probability of finding work; From the point of view of job seekers, however, a vacancy can be filled faster if it is smaller ( ). The so-called search externalities as a result of an increase in the number of seekers can be explained with a similar justification: An additional seeker increases the probability that another job provider will not find employment (this is currently ) and reduces the probability that a company cannot fill a position ( this is ).

A distinction is then made between two flow variables, the flow from the pool of employees into the pool of unemployed (job destruction) and the reverse case (job creation). In this simplified model, unemployment occurs solely as a result of idiosyncratic productivity or output shocks that "come up" with a certain probability ( ) on a specific employment relationship. In contrast to more complex models, in which these shocks only lead to a termination of the employment relationship with a certain probability, we assume here that every shock leads to separation from the employee. If one then assumes for a short period of time that is constant, the average number of those who become unemployed is - is the number of employees. In the same interval, however, some unemployed people are again in employment. Because the number of unemployed is and has already been found above as the probability that an unemployed person will find a job, we can quantify the average number of those who find employment in that time by .

In the steady state, entries and exits to the unemployment pool must be exactly the same, that is . If you solve this equation for , the result is

- .

This is an equilibrium condition. It assigns an unemployment rate to a given churn rate and market tension ; what is so defined is called equilibrium unemployment. The so-called Beveridge curve is given by the condition . Graphically represented in a -diagram it becomes evident that unemployment is negatively dependent on market tension . The higher the market tension, i.e. the higher the number of vacancies in relation to the number of workers, the lower the unemployment rate. An exogenous increase in the churn rate means that, given market tension, unemployment rises, so that the curve shifts upwards. If the relationship is transferred to a diagram, the corresponding curve also shows a falling course. The higher the number of vacancies, the higher the market tension and the lower the unemployment. Here, an increase in causes the curve to shift to the right because the corresponding unemployment rate is now higher for every given proportion of vacant positions.

Job creation

The steady state condition incorporated in the Beveridge curve contains a variable that is still largely undetermined (the model does not yet contain any information about what the number of vacancies results from); It can, however, show that this a unique value can be determined by the model assumptions, so that the equilibrium unemployment to any loss and is uniquely determined given market condition.

When is a worker hired? Assume that every company can hire exactly one worker at a time, can always fire him and does so as soon as it hits a corresponding shock, and can only produce if it has employed one worker. The productivity of the worker is generally the value of the output and amounts to (fixed working hours); the recruitment costs are proportional to productivity and amount per unit of time ( stands for search costs or the costs of concluding a contract, for example); the wage costs are given by. The market value of an occupied position is that of a vacancy . In order to reach the so-called job creation condition, it is necessary to explicitly calculate these two market values.

- : In the optimum, the expected profit that the company will generate from an open position corresponds to the expected return that the investment of the market value of the vacancy would bring in the capital market. The investment in the vacancy costs initially . It is likely that the vacancy will be filled and will then generate a profit of . On the other hand, if you invest the market value on the capital market, you get a return of (with the interest rate). In equilibrium, the following applies .

- Since in equilibrium the companies exploit all profit opportunities through the creation of new jobs, the market value of a vacancy there is zero. With the equation just derived it therefore follows .

- : First of all, an occupied position brings net income of (output value minus wages). However, the job will most likely be destroyed (and profitable ) by an idiosyncratic shock , otherwise it will persist and profit . Because the equilibrium is zero anyway (see previous point), there is a probability that the company will lose . Again, in the optimum, the expected profit from an occupied position is identical to the expected return that the investment of the market value of the occupied position would yield in the capital market. It follows . Substituting in the result from the previous point provides

- .

Workers

After the perspective of the company and thus that of the job seeker was taken in the previous section, the behavior of the job provider will be considered in the following. For the sake of simplicity, the various influences of the job seeker on the equilibrium result are not taken into account here. Instead of influencing the search behavior or the behavior in wage negotiations, as is obvious in reality, only one channel of influence is modeled in this basic model - the wage level; be constant and the labor productivity of all workers is identical. If an actor is employed, his income is equal to, while looking for a job (or unemployment) it amounts to (unemployment benefit, "depriving" or similar), whereby here, again for the sake of simplicity, it is assumed that it does not depend on the market situation. Every worker is either busy or looking for a job at all times.

Let be the present value of future income from unemployment and the present value of future income from employment. The following considerations apply to and :

- : The present value of the future income of an employee is composed on the one hand of the wages ; however, there is also the risk of losing one's job again. In this case, the actor experiences an income loss of . This results in the expected period income of an employee . Optimally, this must be equal to the amount that the employee could get on the capital market for investing this sum. Thus applies . (That is how long the employee continues to work; what we are assuming here is sufficient .)

- : The present value of the future income of an unemployed person is composed on the one hand of the direct income that he can generate in the state of inactivity ( ); however, he is likely to find work again and thus experience an income gain of . This results in the expected period return of an unemployed person . Optimally, this must be equal to the amount that the employee could get on the capital market for investing this sum. Thus applies .

Wage negotiations

It is believed that after a successful meeting between worker and employer, a wage will be negotiated. In contrast to the Walrasian model, the amount of the wage has no market-clearing function and it is by no means the result of an over- or undercutting competition on the part of the labor supply or demand side. Rather, the wages in the everyday life of the matching actors are the channel through which the monopoly rent is divided in the bilateral monopoly that arises during the match . It must first be considered that the total return that results in equilibrium from an occupied position is higher than the sum of the market value of the occupied job (the "benefit for the company") and the present value of the future income of the employee (the "Benefit to the worker"); this is because the destruction of the employment relationship would result in search costs for both sides again. The pension from a match is therefore for the company , for the worker, and thus in total .

The division of this match pension takes place when the two actors meet by means of a Nash negotiation game . If the axiom of symmetry is disregarded, it is through

a Nash solution, namely the so-called general Nash solution , where ( ) indicates the bargaining power of the worker and that of the company. A necessary condition for solving the problem is that for with and it follows that (so it reappears here by specifying the share of the worker in the employer's excess return from the creation of the job). For is again in equilibrium , so the wage equation is now also called

can be written (represented graphically by the wage curve).

A variety of conclusions can be drawn from the wage equation about the wage formation process in the matching models. For example, high market tension implies a high wage rate, as providers of work have greater bargaining power due to the higher vacancy to unemployed ratio. The same applies to income in the event of unemployment - - which can be viewed here as a direct outside option (and thus strengthening the negotiating position). High recruitment costs also contribute to a relatively high wage, which is intuitively based on the fact that companies with higher recruitment costs also save higher costs by quickly filling their offer. The slope of the wage curve is . A marginal change in market tension therefore leads to greater wage gains the higher the average hiring costs.

balance

The unique matching equilibrium is marked by a tuple . On this point are both

- the equation of the Beveridge curve,

- the job creation condition as well

- the wage equation

Fulfills. The JC condition and the wage equation define the equilibrium and the equilibrium wage rate for a given interest rate (job creation curve and wage curve act as a matching theoretical substitute for the neoclassical labor demand and labor supply curve); with then follows from the Beveridge curve equilibrium unemployment .

The following table, based on Wagner / Jahn, gives an overview of the implications of parameter changes:

Overview of the effect of changing parameters on the components of the matching equilibrium … leads to …

For example, a positive productivity shock ( ) leads to a higher wage level and a lower unemployment rate by shifting the wage curve up and the JC curve to the right. This means that the effect on wages is immediately apparent. The positive effect on the unemployment rate cannot be seen directly analytically, because it is theoretically conceivable that the shift in the JC curve in relation to that of the wage curve is so strong that the market tension falls instead of rising, as intuitively assumed. However, it can be shown that based on the assumption that is strictly less than one, such an effect does not occur.

An increase in the discount rate , however, will cause wages to fall and unemployment to rise. While the wage curve remains unaffected, such a shock leads to a left shift in the JC curve, which results in a lower equilibrium wage level and less tension due to the positive slope of the wage curve. This follows the intuition that workers with a high preference for the present are more willing than others to accept offers that are not well paid.

It was already clear before that a higher wage goes hand in hand with a higher wage; the overall consideration in this section shows that this is also the case in the equilibrium state. In addition, it becomes clear that the employees' greater bargaining power - graphically via the upward shift in the wage curve and the associated decrease in market tension - also leads to higher unemployment.

discussion

The matching model outlined above allows many insights into the everyday model life of market players, but at the same time it offers a powerful basis for expansion. An important component of the models used in practice is the modeling of decisions about the use of capital. Just as in the short-term neoclassical model the change in the capital stock and any substitution or complementarity relationships between the production factors capital and labor were not taken into account, the capital stock also only appeared here as a fixed, given variable (included in productivity). Modern matching models endogenize the capital decision.

Another important factor is the simplistic assumption of identical wages that are offered for each offer and are usually abandoned in modern models; On the other hand, based on the search theory principles presented above, one would expect that the wage level of the offers is at least partially subject to a random process; A simple possibility for implementation here is to use a distribution function for the productivity of the matches (the wages then adapt to this).

Since the mid-nineties , a model approach now known as the Diamond-Mortensen-Pissarides model (DMP model) has prevailed in the field of matching theory , which is now the “current standard model of matching theory”. The model, based on an article by Dale Mortensen and Christopher Pissarides from 1994, takes into account the fact that the productivity of a job does not remain constant over the duration of the employment relationship, as in the basic model, but rather is subject to considerable job-specific fluctuations on the job , such as they already imply the empirically proven existence of business cycles . The productivity shocks then have an impact on the market participants, both on the productivity of the existing jobs and any new offers that may be created; a Poisson process models the arrival rate of corresponding shock events. A decision-making process then begins in the DMP model, in the course of which, based on an adjustment of the market value of the employment relationship, it is determined whether the company should leave the market entirely, the wage level should be renegotiated or an existing job should be destroyed or not. Wage negotiations are therefore not limited to recruitment, but are also used in existing employment relationships. Exogenous shocks, for example an increase in unemployment benefits, no longer only affect the job creation process as in the basic model above, but also the job destruction process; the previously exogenous separation decision is, in other words, endogenized. Since then, large parts of the theory of labor economics have been based on the DMP model. Extensions to the model take into account, for example:

- Job-to-job movements (creation and destruction of employment relationships are related there)

- On-the-job search efforts by employees, by which it is meant that the employees do not immediately stop their search efforts after accepting a job offer;

- the explicit modeling of the heterogeneity of workers and / or firms.

An overview of the various explicit matching functions can be found in Petrongolo / Pissarides 2001.

Another class of models is that of the competitive search models ( going back to Moen 1997, among others), in which the random arrival of workers at a company (as in the basic matching theoretical model or the DMP model) is replaced by a two-stage solution: First, a group does a wage offer from actors, then the other group selects the most lucrative offer. In a simple version, for example, companies (workers) make an offer and the workers (companies) then decide on the highest (lowest). The primary distinguishing feature from the matching models outlined above is the assumption of the targeted search process (directed search). In contrast to the classic matching models, competitive search models sometimes also deliver socially efficient negotiation results. Regardless of the methodological proximity, such models with targeted search processes offer greater insight into the matching and negotiation process: while in the DMP model, for example, the match rent is divided exogenously as part of the Nash negotiation game (ex post), the division here is in the power of the matching actors - workers or companies are in a constant trade-off between the probability of employment and the wage amount when making their ex-ante decision on the wage level offered. Versions of the model also include specific heterogeneity factors that lead to friction.

literature

- Pierre Cahuc, André Zylberberg: Labor Economics. MIT Press, Cambridge et al. a. 2004, ISBN 0-262-03316-X .

- Ronald G. Ehrenberg, Robert S. Smith: Modern Labor Economics. Theory and Public Policy. 6th edition. Addison-Wesley Longman, Amsterdam a. a. 1997, ISBN 0-673-98013-8 .

- Wolfgang Franz : Labor Economics. 6th edition. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 2006, ISBN 3-540-32337-6 , doi : 10.1007 / 3-540-32338-4 (digitized version).

- Richard B. Freeman: Labor economics. In: Steven N. Durlauf, Lawrence E. Blume (Eds.): The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. 2nd Edition. Palgrave Macmillan. (Online edition)

- Berndt Keller : Introduction to Labor Policy. 7th edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-58475-2 .

- Brian P. McCall, John J. McCall: The Economics of Search. Routledge, London 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-29992-3 , e-book ISBN 978-0-203-49603-9 . [In particular chap. 6-11.]

- Paul J. McNulty: The Origins and Development of Labor Economics. A Chapter in the History of Social Thought. MIT Press, Cambridge / London 1980, ISBN 0-262-13162-5 .

- Christopher Pissarides : Equilibrium Unemployment Theory. 2nd Edition. MIT Press, Cambridge 2000, ISBN 0-262-16187-7 . (Technical treatise on matching theory)

- Werner Stuhlmeier, Gregor Blauermel: Labor market theories . An overview. 2nd Edition. Physika 1998, ISBN 3-7908-1057-6 . (Non-technical overview)

- Stephen Smith: Labor Economics. 2nd Edition. Routledge, London 2003, ISBN 0-415-25985-1 , e-book ISBN 978-0-203-42285-4 .

- Hal Varian : Intermediate Microeconomics. A modern approach. 7th edition. WW Norton, New York / London 2006, ISBN 0-393-92862-4 . (Introductory textbook on microeconomics, on the labor market see Chapters 8 and 9)

- Thomas Wagner, Elke J. Jahn: New labor market theories. 2nd Edition. Lucius & Lucius (UTB), Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8282-0253-5 .

- Jürgen Zerche, Werner Schönig, David Klingenberger: Labor market policy and theory. Oldenbourg, Munich / Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-486-25413-8 .

Web links

- Daron Acemoğlu and David Author: Lectures in Labor Economics ( English , PDF; 2.3 MB) Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- University of St. Gallen , Research Foundation for Economics: Labor Market and Unemployment ( mostly German, partly English ). Accessed on March 7, 2012. [Explanations on the neoclassical standard model; Java applet for simulating a labor market consisting of companies and trade unions]

Remarks

- ↑ The presentation of the premises largely follows Keller 2008, p. 270 and Stuhlmeier / Blauermel 1998, p. 47 f.

- ↑ See Alfred Endres and Jörn Martiensen: Microeconomics. An integrated presentation of traditional and modern concepts in theory and practice. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-17-019778-7 , p. 169.

- ↑ See Wagner / Jahn 2004, p. 15 and explicitly Franz 2006, p. 27.

- ↑ See Franz 2006, p. 28.

- ↑ To put it precisely, the optimization problem would also have to be supplemented by the conditions and . This is omitted here, as is regularly the case in the introductory literature. If you want to take them into account, you can solve the resulting problem using the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker conditions , for example . On this in detail Franz 2006, pp. 28–30 and Cahuc / Zylberberg 2004, pp. 7 f.

- ↑ It can easily be shown that the properties of strict monotony and convexity of an indifference curve follow directly from the above assumption of the quasi-concavity of the utility function. Evidence can be found, for example, in Cahuc / Zylberberg 2004, p. 53.

-

↑ That the marginal rate of substitution (MRS) corresponds to the marginal utility ratio of leisure and consumption can be seen using the total differential of the utility function. This is

- .

- ,

- ,

- ^ Franz 2008, p. 30. See also Alfred Endres and Jörn Martiensen: Mikroökonomik. An integrated presentation of traditional and modern concepts in theory and practice. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-17-019778-7 , p. 170.

- ↑ The following presentation of the two forms of the income effect follows Varian 2006, p. 174 ff .; similar to Cahuc / Zylberberg 2004, p. 10f.

- ↑ See Varian 2006, p. 175 f., Wagner / Jahn 2004, p. 22 and Zerche / Schöning / Klingenberger 2000, p. 193.

- ↑ See Ehrenberg / Smith 1997, p. 184, on the observation of decreasing working hours from a certain income level also Cahuc / Zylberberg 2004, p. 12. A detailed (model-based) analytical study of the curve can be found, for example, in Thorsten Hens and Paolo Pamini: Grundzüge of analytical microeconomics. Springer, Berlin and Heidelberg 2008, ISBN 978-3-540-28157-3 , in particular p. 59 ff.

-

↑ As a further specification, one speaks of an inelastic labor supply curve, and of an elastic one. An analogous concept also exists for the response of the labor supply to changes in total income . This income elasticity of work is given accordingly by

- ^ Gary S. Becker: A Theory of the Allocation of Time. In: The Economic Journal. 75, No. 299, 1965, pp. 493-517 ( JSTOR 2228949 ).

- ^ Pierre-André Chiappori: Rational Household Labor Supply. In: Econometrica. 56, No. 1, 1988, pp. 63-89 ( JSTOR 1911842 ); Ders .: Collective Labor Supply and Welfare. In: Journal of Political Economy. 100, No. 3, pp. 437-467 ( JSTOR 2138727 )

- ↑ See Cahuc / Zylberberg 2004, pp. 35–38. See also, among others, Jeremy A. Hausman: The econometrics of labor supply on convex budget sets. In: Economics Letters. 3, No. 2, 1979, pp. 171-174, doi : 10.1016 / 0165-1765 (79) 90112-5 ; Ders .: Taxes and Labor Supply. In: Alan J. Auerbach, Martin Feldstein (Eds.): Handbook of Public Economics. Vol. 1, Elsevier Science Publishers, North-Holland 1985, ISBN 0-444-87667-7 , pp. 213-263, doi : 10.1016 / S1573-4420 (85) 80007-0 (digitized version); Richard Blundell and Thomas Macurdy: Labor supply: A review of alternative approaches. In: Orley C. Ashenfelter and David Card (Eds.): Handbook of Labor Economics. Vol. 3, Part A, Elsevier Science Publishers, North-Holland 1999, ISBN 0-444-50187-8 , pp. 1559-1695, doi : 10.1016 / S1573-4463 (99) 03008-4 (digitized version)

- ↑ See Franz 2006, p. 103.

- ↑ See Cahuc / Zylberberg 2004, p. 172.

- ↑ See Stuhlmeier / Blauermel 1998, p. 50; Cahuc / Zylberberg 2004, p. 172.

- ↑ See Wagner / Jahn 2004, p. 26 ff. And Gunther Markwardt: Arbeitsmarkttheorie. Internet archive link ( Memento of the original from May 21, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (June 17, 2010).

- ↑ This is also sufficient because . This follows from condition (3).

- ↑ Sometimes the term "assessed (factor) marginal productivity" is also used.

-

↑ Because:

-

↑ You can of course also consider the first expression for the maximization condition. Because according to the laws of supply and demand is negative (the higher the amount offered, the lower the price), is

- ↑ See Ehrenberg / Smith 1997, p. 72 f.

- ↑ Wagner / Jahn 2004, pp. 36–41.

- ↑ See Cahuc / Zylberberg 2004, p. 12.

- ↑ George J. Stigler: Information in the Labor Market. In: Journal of Political Economy. Vol. 70, No. 5, 1962, ISSN 0022-3808 , pp. 94-105 ( JSTOR 1829106 ).

- ^ JJ McCall: Economics of Information and Job Search. In: The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 84, No. 1, 1970, pp. 113-126 ( JSTOR 1879403 ).

- ^ Dale T. Mortensen: A Theory of Wage and Employment Dynamics. In: ES Phelps (Ed.): Microeconomic Foundations of Employment and Inflation Theory. New York 1970 (WW Norton), pp. 124-166.

- ↑ Assumptions and formulas follow the model described by Franz 2006, pp. 211–215.

- ↑ See Smith 2003, chap. 9.

- ↑ Randall D. Wright: Search, Layoffs, and Reservation Wages. In: Journal of Labor Economics. 5, No. 3, 1987, pp. 354-365 ( JSTOR 2535025 ).

- ↑ Kenneth Burdett: A Theory of Employee Job Search and Quit Rates. In: The American Economic Review. 68, No. 1, 1978, pp. 212-220 ( JSTOR 1809701 ).

- ^ Michael Rothschild: Searching for the Lowest Price When the Distribution of Prices Is Unknown. In: Journal of Political Economy. 82, No. 4, 1974, pp. 689-711 ( JSTOR 1837141 ).

- ↑ Kenneth Burdett and Tara Vishwanath: Declining Reservation Wages and Learning. In: The Review of Economic Studies. 55, No. 4, 1988, pp. 655-665, doi : 10.2307 / 2297410 .

- ^ For example, David M. Blau: Search for Nonwage Job Characteristics: A Test of the Reservation Wage Hypothesis. In: Journal of Labor Economics. 9, No. 2, 1991, pp. 186-205 ( JSTOR 2535240 ).

- ^ Christopher A. Pissarides: Short-Run Equilibrium Dynamics of Unemployment, Vacancies, and Real Wages. In: The American Economic Review. 75, No. 4, 1985, pp. 676-690 ( JSTOR 1821347 ).

- ^ Peter Diamond: Wage Determination and Efficiency in Search Equilibrium. In: The Review of Economic Studies. 49, No. 2, 1982, pp. 217-227, doi : 10.2307 / 2297271 .

- ↑ Pissarides 2000, chap. 1.

- ^ Economic Sciences Prize Committee of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences: Markets with Search Frictions. Scientific Background on the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2010. Stockholm 2010, Internet http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/laureates/2010/advanced-economicsciences2010.pdf (accessed February 11 2012).

-

↑ For the purposes of this article, irrelevant, but essential for applications based on the model, is the merging of these two equations, i.e. of and . The two equations initially imply . It follows again from this

- .

- ↑ Then applies to a given negotiation game (with the guaranteed benefit): Is , then follows from directly . See also the article negotiated solution .

- ↑ denotes the argument of the maximum .

- ↑ Follows from the mentioned necessary condition (taking into account in equilibrium) together with and (see above).

- ↑ See Pissarides 2000, p. 20 for details.

- ↑ See, for example, Richard Rogerson, Robert Shimer, Randall Wright: Search-Theoretic Models of the Labor Market: A Survey. In: Journal of Economic Literature. 18, No. 4, 2005, pp. 959–988 ( online free of charge ; PDF; 338 kB), doi : 10.1257 / 002205105775362014 , here p. 971.

- ↑ Wagner / Jahn 2004, p. 64.

- ^ Dale T. Mortensen, Christopher A. Pissarides: Job Creation and Job Destruction in the Theory of Unemployment. In: The Review of Economic Studies. 61, No. 3, 1994, pp. 397-415, doi : 10.2307 / 2297896 .

- ↑ In particular Dale T. Mortensen: The cyclical behavior of job and worker flows. In: Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control. 18, No. 6, 1994, pp. 1121-1142, doi : 10.1016 / 0165-1889 (94) 90050-7 .

- ↑ See for example Pissarides 2000, chap. 4th

- ↑ Examples include Dale T. Mortensen, Christopher A. Pissarides: Unemployment Responses to "Skill-Biased" Technology Shocks: The Role of Labor Market Policy. In: The Economic Journal. 109, No. 455, 1999, pp. 242-265, doi : 10.1111 / 1468-0297.00431 ; Daron Acemoğlu : Changes in Unemployment and Wage Inequality: An Alternative Theory and Some Evidence. In: American Economic Review. 89, No. 5, 1999, pp. 1259-1278, doi : 10.1257 / aer.89.5.1259 ; Ders .: Good Jobs versus Bad Jobs. In: Journal of Labor Economics. 19, No. 1, 2001, pp. 1-21, doi : 10.1086 / 209978 ; James Albrecht and Susan Vroman: A Matching Model with Endogenous Skill Requirements. In: International Economic Review. 43, No. 1, 2002, pp. 283-305, doi : 10.1111 / 1468-2354.t01-1-00012 .

- ↑ Barbara Petrongolo and Christopher A. Pissarides: Looking into the Black Box: A Survey of the Matching Function. In: Journal of Economic Literature. 39, No. 2, 2001, pp. 390-431 ( JSTOR 2698244 , freely available version ; PDF; 384 kB).

- ^ Espen R. Moen: Competitive Search Equilibrium. In: Journal of Political Economy. 105, No. 2, 1997, pp. 385-411, doi : 10.1086 / 262077 .

- ↑ Cf. Moen ibid .; also extensively on modifications Dale T. Mortensen, Christopher A. Pissarides: New developments in models of search in the labor market. In: Handbook of Labor Economics. Vol. 3, Part B, 1999, ISBN 0-444-50188-6 , doi : 10.1016 / S1573-4463 (99) 30025-0 (digitized version), pp. 2567-2627, here pp. 2589 ff.

- ↑ See Richard Rogerson, Robert Shimer, Randall Wright: Search-Theoretic Models of the Labor Market: A Survey. In: Journal of Economic Literature. 18, No. 4, 2005, pp. 959–988 ( online free of charge ; PDF; 338 kB), doi : 10.1257 / 002205105775362014 , here p. 975 f.

- ^ For example, Robert Shimer: The Assignment of Workers to Jobs in an Economy with Coordination Frictions. In: Journal of Political Economy. 113, No. 5, 2005, pp. 996-1025, doi : 10.1086 / 444551 .

![{\ displaystyle {\ underset {{\ overline {K}}, L} {\ Pi}} = \! \, \ underbrace {P [F (L)] \ cdot F (L)} _ {\ text {Sales }} - \ underbrace {W \ cdot L} _ {\ text {labor costs}} - \ underbrace {(R \ cdot {\ overline {K}} + T)} _ {\ text {fixed costs}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d61ff3b7ae493757b7d12b34e10a38612474a124)

![{\ displaystyle \ Pi _ {L} = F '(L) \ cdot P \! \,' [F (L)] \ cdot F (L) + P [F (L)] \ cdot F \! \, '(L) -W = 0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b1ecf0242a815d9f0d3e9dcc29321b8a2a9e058c)

![{\ displaystyle \ Pi _ {L} = P \ times F \! \, '(L) - [W \! \,' (L) \ times L + W (L)] = 0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fd6f95909d46c0289adaa2416530e0b8f20b888f)

![{\ displaystyle {\ frac {(uc) (1 + r)} {r + p (\ mathbf {z}, w ^ {R})}} + p (\ mathbf {z}, w ^ {R}) \ cdot \ mathbb {E} (w \ mid w \ geq w ^ {R}) \ cdot {\ frac {1 + r} {r [r + p (\ mathbf {z}, w ^ {R})] }}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/267369a274261259bbb96cdd4197381da3557d7f)

![{\ displaystyle 1 / [\ theta q (\ theta)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e225fe4532f40565d04864cd627e7696541a4ab5)

![{\ displaystyle rW-rU = w-z + \ lambda (UW) - \ theta q (\ theta) (WU) = w-z + [- \ lambda - \ theta q (\ theta)] (WU)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f5657c900e26d2577f039724b3bf04ca7165b91e)

![{\ displaystyle (WU) [r + \ lambda + \ theta q (\ theta)] = wz \ implies WU = {\ frac {wz} {r + \ lambda + \ theta q (\ theta)}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5044c989f4c63fb7fefad19459d18aac90bc2f16)

![{\ displaystyle rW = w- \ lambda {\ frac {wz} {r + \ lambda + \ theta q (\ theta)}} = {\ frac {w [r + \ lambda + \ theta q (\ theta)] - \ lambda (wz)} {r + \ lambda + \ theta q (\ theta)}} = {\ frac {\ lambda z + [r + \ theta q (\ theta)] w} {r + \ lambda + \ theta q (\ theta )}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d1137df317c07539e20f86e02d6084c72e081d5f)

![{\ displaystyle rU = z + \ theta q (\ theta) {\ frac {wz} {r + \ lambda + \ theta q (\ theta)}} = {\ frac {z [r + \ lambda + \ theta q (\ theta )] + \ theta q (\ theta) (wz)} {r + \ lambda + \ theta q (\ theta)}} = {\ frac {(r + \ lambda) z + \ theta q (\ theta) w} {r + \ lambda + \ theta q (\ theta)}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e102e8cc4e577ca1f86d1edc40561da4299d881e)