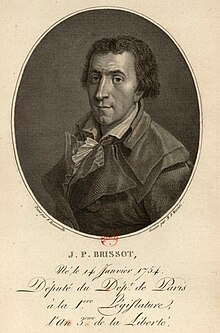

Jacques Pierre Brissot

Jacques-Pierre Brissot de Warville , called Brissot (born January 15, 1754 in Chartres , † October 31, 1793 in Paris), publicist and journalist, was a Jacobin and later leader of the Girondins , a group of moderate republicans during the French Revolution .

Life

Chartres, Paris and abroad

Jacques-Pierre Brissot was born in Chartres on January 15, 1754, the thirteenth of seventeen children of an innkeeper. His father, the wealthy owner of a restaurant, enabled him to get a good education at the municipal collège . After finishing school, Jacques-Pierre began his professional training with a lawyer in Chartres. At the age of eighteen he left his hometown and moved to Paris. No longer supported by his father, he got by with casual writing and then found a job at the Nolleau law firm. From 1774 he called himself Jacques-Pierre Brissot de Warville, after the changed English name of the village Ouarville near Chartres, where he had spent the first years of his life with a wet nurse.

A study of law seemed unattractive to Brissot; he felt called to be a writer. In Paris he planned his Théorie des lois criminelles , his first major work that made him famous. He sent the preface to Voltaire , who thanked him with a flattering and encouraging reply. To make money, Brissot wrote articles for the Mercure . In 1778 and 1779 he worked as an editor at the Courrier de l'Europe , an English paper with a French edition in Boulogne-sur-Mer , which campaigned for the insurgents in America. He felt cramped there by the censorship and went back to Paris.

In Paris he devoted himself to scientific studies, especially in the field of chemistry. During this time he was admitted to the bar in Reims; he received two prizes from the Académie de Châlons . The doctrine that property was theft, which later became famous through Proudhon , forms the core thesis of his book Recherches philosophiques sur le droit de propriété et sur le vol… (1780). He conceived his Traité de la vérité , published his Théorie des lois criminelles (1781) and his Bibliothèque des lois criminelles (1782). Brissot also wrote pamphlets entitled l'Inégalité sociale at the same time . From 1782 to 1786 his ten-volume Bibliothèque philosophique du législateur was published , a work based on the ethical principles of Rousseau . Brissot married Félicité Dupont (1759-1818) in 1783, and the connection resulted in three children.

From February to November 1783 he lived with his wife in London. There he wanted to create an institution, a lyceum in the ancient sense, which would give all scholars in Europe the opportunity to inform one another about the knowledge they had gained. The Journal du Lycée de Londres published by him was intended to serve as a mouthpiece for the members. Due to financial disputes with the editor of the Courrier de l'Europe , his old employer, Brissot came in London in debtors' prison . He had to give up the Lycée project .

A few days after his return to France, Brissot was arrested and detained in the Bastille on charges of having written a pamphlet against Queen Marie-Antoinette . It was not until four months later that he was released in September 1784 thanks to the help of influential advocates. Through the intercession of his wife, who was employed in the family of the Duke Louis-Philippe of Orléans as a tutor, Brissot was in the service of the Duke until 1788 with the title lieutenant-général de la chancellerie . In this capacity he took part in the Brabant uprising in the Netherlands in October 1787 . When the Louis-Philippes law firm became involved in a plot, Brissot fled to London in time. During this second stay in England he made the acquaintance of leading English abolitionists who campaigned for the abolition of the slave trade. Inspired by their example, he founded the Société des Amis des Noirs in France in February 1788, together with the Geneva banker Étienne Clavière and Count Mirabeau . On behalf of this society, Brissot traveled to the United States in May 1788 to find out about the possibilities of emancipating the colored population. He stayed in the USA for four months, together with Clavière, who was with him. In 1789 Brissot was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences .

The revolution

Brissot returned to France for the elections to the Estates- General . He published a large number of revolutionary writings that drew attention to him and only missed the election of a member of the assembly by a few votes. In May 1789 he founded the republican newspaper Le Patriote français , which appeared until June 2, 1793; it became the organ of the future Brissotins and Girondists. The always well-informed journalist and Jacques-Pierre Brissot, known for his speeches in the Jacobin Club , was elected to the first Paris municipalité . As the representative of the conseil municipal (city council), the rebels handed him the key to the stormed Bastille in a symbolic act on July 14, 1789 . Although he was not a member of the National Assembly , he was appointed to its constitutional committee as a publicist.

In 1790 and 1791 Jacques-Pierre Brissot was president of the Société des amis des Noirs . In 1791 he published his three-volume Nouveau voyage dans les Etats-Unis de l'Amerique septentrionale . After the escape of the royal family in June 1791, he wrote the petition to depose the king who immediately before the July 17 massacre in the Campus Martius was read. Against opposition from the court and the royalists , he was elected to the Legislative Assembly ( Assemblée législative ) in August 1791 as one of the 24 deputies from Paris and one of the few Jacobins . His experience abroad enabled him to influence French foreign policy in the comité diplomatique . War, argued Brissot, could only strengthen the revolution by unmasking all its opponents; a war against the monarchs in Europe also opens a crusade for general freedom. He had a major influence on France's declaration of war on Austria on April 20, 1792, the symbol of the ancien régime . Brissot became the spokesman of the left-wing group named after him in the legislature , the Brissotins , the later Girondists. He was at the height of his political activity, but his war policy led to a conflict with Maximilien de Robespierre . The early setbacks by French forces, ill-coordinated government policies, and Brissot's reluctance to take on the Lafayette case cost him much of his credibility and authority. At the events of August 10, 1792 - the storming of the Tuileries and the abolition of kingship - he did not appear and he was one of the few MPs who condemned the September massacres. Brissot was the target of increasingly violent attacks by his opponents: Robespierre accused him of treason on September 1 in front of the Paris Commune.

In early September 1792, Brissot was elected to the National Convention ( Convention nationale ) by the Eure-et-Loir department ; he had not run again in Paris, this time presumably without a chance there. In the convent he was the leader of the Girondins, attacked by the Montagnards . He and his friends, the Brissotins, fought against Jacobin politics and against anarchy. They were expelled from the Jacobin Club in October. Brissot attacked the Paris Sections, the Paris Commune, the Montagnards and especially Robespierre. First he fought against the death sentence for Louis XVI. ; in the trial against the king he finally voted for the death penalty, subject to the approval of the guilty verdict by the people and the postponement of execution until peace. He still had influence in the Convention: his reports in the comité diplomatique led to declarations of war on England and Holland on February 1, 1793. Previously, on January 4, he had been appointed to the General Defense Committee. In April Robespierre accused him of complicity in General Dumouriez's treason ; this ruined Brissot's reputation in public opinion. Brissot resisted in May with a letter in which he called for the closure of the Jacobin Club and the dissolution of the Paris Commune. On June 2, his arrest and house arrest were decided. Brissot fled and came to Moulins in the Allier department in Auvergne. There he was discovered and arrested; on June 22nd he was imprisoned in the Abbaye in Paris and then in the Conciergerie . In prison he wrote his memoirs under the title Legs à mes enfants . On October 30, 1793, Jacques-Pierre Brissot de Warville was sentenced to death by the Revolutionary Tribunal along with twenty-one Girondins . At the age of thirty-nine, he died the following day by guillotine on Place de la Révolution . His last words were: "This is more than despotism."

Characteristics

The Encyclopedia Britannica describes Brissot as "an alert, zealous, impulsive man of wide knowledge, but who was indecisive and unable to fight the wild energies aroused by revolutionary events."

The French historian and politician Max Gallo writes: “Superficial, quick, inventive, Brissot did not understand that the revolution demands other qualities than those of a journalist with great talent. He risked his life through a few empty phrases that jeopardized the fate of the country and which he could no longer delete, like in the manuscript of a script that was written too quickly. "

Works

- Research philosophiques sur le droit de propriété considéré dans la nature, pour servir de premier chapitre à la “Théorie des lois” de M. Linguet . Paris, 1780, 128 p., In-8 °.

- Bibliothèque philosophique du Législateur, du Politique et du Jurisconsulte , Berlin et Paris, 1782-1786, 10 vol. in-8 °.

- Moyens d'adoucir la rigueur des lois pénales en France sans nuire à la sécurité publique , Discours couronné par l'Académie de Châlons-sur-Marne en 1780, Châlons, 1781, in-8 °.

- Théorie des lois criminelles , Paris, 1781, 2 vol. in-8 °.

- De la Vérité des Méditations sur les moyens de parvenir à la vérité dans toutes les connaissances humaines , Neufchâtel et Paris, 1782, at-8 °.

- Discours sur la nécessité de maintenir le décret rendu le 13 may 1791, en faveur des hommes de couleur libres, prononcé le 12 septembre 1791, à la séance de la Société des Amis de la Constitution, séante aux jacobins .

- Discours sur la nécessité politique de révoquer le décret du 24 septembre 1791, pour mettre fin aux troubles de Saint Domingue; prononcé à l'Assemblée nationale, le 2 mars 1792. Par JP Brissot, député du département de Paris , Paris: De l'Imprimerie du patriote françois, 1792.

- Correspondance universelle sur ce qui intéresse le bonheur de l'homme et de la société , Londres et Neufchâtel, 1783, 2 vol. in-8 °.

- Journal du Lycée de Londres, ou Tableau des sciences et des arts en Angleterre , Londres et Paris, 1784.

- Tableau de la situation actuelle des Anglais dans les Indes orientales, et Tableau de l'Inde en général , ibid. , 1784, in-8 °.

- L'Autorité législative de Rome anéantie , Paris, 1785, in-8 °, réimprimé sous le titre: Rome jugée, l'autorité du pape anéantie, pour servir de réponse aux bulles passées, nouvelles et futures du pape , ibid. , 1731, mg.

- Examen critique des voyages dans l'Amérique septentrionale, de M. le marquis de Chatellux, ou Lettre à M. le marquis de Chatellux, dans laquelle on réfute principalement ses opinions sur les quakers, sur les nègres, sur le peuple et sur l ' homme, par J.-P. Brissot de Warville , Londres, 1786, in-8 °.

- Discours sur la Rareté du numéraire, et sur les moyens d'y remédier , 1790, in-8 °.

- Mémoire sur les Noirs de l'Amérique septentrionale , 1790, at -8 °.

- Voyage aux États-Unis , 1791.

- Mémoires de Brissot ... sur ses contemporains, et la révolution française; publ. par son fils; notes et éclaircissements hist. par MF de Montrol , 1830-1832; Vol. I (1830) ; Vol. II (1830) ; Vol. III (1832) ; Vol. IV (1832) .

literature

- Eloise Ellery: Brissot de Warville. A study in the history of the French revolution . AMS Press, New York 1970 (reprinted from the Boston MA 1915 edition).

- Suzanne d'Huart: Brissot, la Gironde au pouvoir . Robert Laffont, Paris 1986, ISBN 2-221-04686-2 (Les hommes et l'histoire).

- Leonore Loft: Passion Politics and Philosophy. Rediscovering J.-P. Brissot . Greenwood Press, Westport CT 2002, ISBN 0-313-31779-8 (Contributions to the study of world history; 84).

- Jean-Chrétien-Ferdinand Hoefer: Jacques-Pierre Brissot . In: Nouvelle biographie générale Hoefer 1852–1866 , Volume 7, Columns 440–443 (French, Wikisource )

- Brissot, Jacques Pierre . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . 11th edition. tape 4 : Bishārīn - Calgary . London 1910, p. 575 (English, full text [ Wikisource ]).

- J.-P. Brissot: Mémoires (1734–1793) , publiés avec étude critique et notes par Cl. Perroud, Picard et fils, Paris 1911 (French). Volume 1 historical.library.cornell.edu and Volume 2 historical.library.cornell.edu

Web links

- Lars Schneider: Brissot, JP historicum.net (with numerous references to sources and literature)

Individual evidence

- ^ Short biography of Brissot.Retrieved February 7, 2012.

- ↑ Joseph A. Schumpeter, (Elizabeth B. Schumpeter, ed.): History of economic analysis. First part of the volume. Vandenhoeck Ruprecht, Göttingen 1965. p. 193

- ↑ Gallery of the Revolution of the French Republic, 1794 , p. 37

- ^ Brissot, Jacques Pierre . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . 11th edition. tape 4 : Bishārīn - Calgary . London 1910, p. 575 (English, full text [ Wikisource ]).

- ↑ To: Notes et Archives 1789−1794 Brissot Archived copy ( Memento of the original from November 25, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Brissot, Jacques Pierre |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Brissot de Warville, Jacques-Pierre |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French revolutionary |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 15, 1754 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Chartres |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 31, 1793 |

| Place of death | Paris |