Carl Durheim's wanted photos of homeless people

Carl Durheim's wanted photographs of homeless people form the world's earliest coherent collection of police photographs . On behalf of the Swiss Confederation , the Bernese lithographer and pioneer photographer Carl Durheim (1810–1890) made photographs of the homeless and non-settled people (often Swiss Yeniche ) who were systematically picked up and held in Bern . Most of the photographs were taken in the “Outer Captivity” - the penitentiary in which the homeless were imprisoned to clarify their civil rights. Durheim took further portraits in his studio in Bern.

Carl Durheim made the prints using the calotype process , then they were lithographed and made available in sheets to the Swiss police stations. The original photographs as well as the bound sheets with the lithographs are stored in the Swiss Federal Archives .

Historical context

The "homeless question"

In the 19th century, “homeless” were those people who did not have any or only insufficient municipal citizenship (e.g. non-settled people, tolerated people, those who were left behind or who were left alone ). Reasons for the homelessness could be a longer absence due to non-settlement, the expatriation in the course of criminal proceedings or a change of religion (e.g. through marriage).

Since the restoration , community citizenship and thus the place of citizenship have become increasingly important. A central component of this civil right was relief for the poor; that is, the community had to bear the cost of caring for its citizens. However, the local authorities tied this citizenship to the fact that they were settled in the community concerned.

As early as the first half of the 19th century, cantonal and federal authorities made several attempts to give the homeless community citizenship rights. Above all, this was intended to counteract impoverishment and misery and to stop the regular expulsions to other cantons. On the other hand, non-sedentary people should be forced into a sedentary way of life, in particular by “giving their children back to the civilized people through early care by righteous house fathers, through getting used to work and through religious and school lessons”.

With the establishment of the federal state in 1848, and in particular with the Federal Law on Homelessness of 1850, the discourse on the "homeless question" passed to the federal level. In addition to “mediating civil rights for the homeless”, the law also pursued the goal of “taking measures to prevent new cases of homelessness”. A "sick condition" should be remedied, "the homeless or at least their children gradually brought back to civilization." The naturalizations, however, did not result in equal citizenship, for example the naturalized homeless were excluded from the use of common goods (e.g. forests , Alps or common land ). In addition, the provisions of the Homeless Act counteracted the non-sedentary lifestyle, for example by banning moving around in families with children.

The Advocate General's mandate

The Federal Council commissioned the Federal Prosecutor's Office under Advocate General Jakob Amiet to investigate civil rights. In the following decades, around 30,000 people were forcibly naturalized. Many non-sedentary people were picked up by the cantonal police , transported to Bern and taken there to investigate. In this context, Attorney General Amiet commissioned Carl Durheim to photograph the homeless. With the photographic capture of the homeless

“The Federal Council wanted to remove a major difficulty in dealing with the issue of the homeless and vagabonds . This difficulty consists in conveying your personality, which is often impossible because by hiding the papers, by constantly changing names and by consistently denying and concealing the circumstances, all efforts of the authorities are often thwarted, and also because where it succeeds In order to find out the real person and send him to his home or to assign him a new home, there is no guarantee that the same person will not appear again later under a different name as allegedly homeless, so that the investigation had to start again. This disadvantage was by no means lifted by the previous signal elements. "

The context in which Durheim's photographs were created and their intended purpose was “the police safeguarding the integration and forced assimilation of a population group whose legal status and way of life was perceived as an intolerable deviation from the norm”.

Durheim's homeless portraits

technology

Durheim was one of the first professional photographers in Switzerland and a well-known daguerreotypist. The photographer and his client soon abandoned the original plan to produce the photographs of the homeless as daguerreotypes, as these were not very suitable for making reproductions. Because the plan was to make lithographs of the photographs in a second step anyway, Durheim decided on prints on paper ( calotype process ) and against the unique metal plates of the daguerreotype, "because in this way you only have to draw the portraits through". He drew the negatives on salt paper, often retouching the background on the negative - the courtyard of the "Outer Captivity" in Bern.

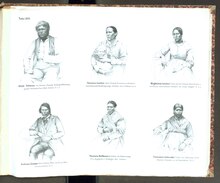

A lithographer then used the prints to produce lithographs on behalf of Durheim, which were used to print the 38 sheets for the wanted books. Six portraits were shown per sheet and provided with information about the people (e.g. names, ages and nicknames). The production of the lithographs also offered the opportunity to trace unrecognizable details of the templates for printing. Durheim used this method to produce all of the photographs that have survived that were made up to June 1853.

While he was still working on the portraits, he got to know the production of glass negatives and subsequently made several homeless portraits using this process. Durheim also used the federal contract to test and apply various procedures.

Staging

Durheim made the first 33 homeless portraits as half-length portraits. Later he took the "whole seated figure" because it seemed more useful for the manhunt. Since photographic recordings in the middle of the 19th century still required very long exposure times, those portrayed were not allowed to move for a long time and not change their facial expressions. To fix the homeless in the desired position in front of the camera, Durheim used head holders.

With the photographic recording procedure, the authorities intended not only to create wanted photos, but also to have a psychological effect on the homeless prisoners. Advocate General Jakob Amiet understood photographic detention as a "measure", as a "moral deterrent against the submission of incorrect information". Because "most of the homeless were already betraying themselves when they sat with their heads screwed tight in front of the machine that produced their image in a few minutes". Since the homeless ran the risk of harming themselves or their loved ones with statements about their biographies, their statements did not always correspond to the truth.

Carl Durheim, experienced in bourgeois portrait photography, occasionally applied a bourgeois staging to portraits of the homeless and chose appropriate props . For example, he equipped his models with books or peaked caps that were presented on a saloon table. The prisoners, who were barely able to read or write, were only rarely depicted with objects from their everyday lives. The few examples show, for example, a basket made by a basket maker or the utensils of a brush binder . In addition, many of the prisoners had to wear peasant robes over their clothes for portraits, which the Advocate General Amiet obtained for them.

Aftermath

In the middle of the 19th century, the large-scale and systematic photographic registration of a selected group was unusual and also attracted attention abroad. However, it did not find any imitators. The Federal Prosecutor's Office also did not consider extending this search to other groups of people; it ended this form of registration in 1854.

See also

Gallery (selection)

literature

- Martin Gasser, Thomas D. Meier and Rolf Wolfensberger: Against denial and misrepresentation - Carl Durheim's wanted photos of homeless people 1852/53. Offizin Verlag, Zurich, Fotomuseum Winterthur , 1998. ISBN 3-907495-86-1

- Thomas Huonker : External and self-images of «Gypsies», Yeniche and homeless people in Switzerland in the 19th and 20th centuries from literary and other texts. In: Herbert Uerlings and Iulia-Karin Patrut: «Gypsies» and Nation. Representation - inclusion - exclusion. Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-631-57996-1

- Thomas D. Meier and Rolf Wolfensberger: A home and yet none. Homeless and non-settled people in Switzerland (16th – 19th centuries). Chronos , Zurich 1998, ISBN 978-3-905312-53-9

- Johann Conrad Vögelin: About the homeless and the duty of their care and naturalization. Ch. Beyel, Frauenfeld 1838, pp. 17–18 ( digitized from Google Books )

Web links

- Regula Argast: Nation and Citizenship . In: Swiss travelers in the past and present. A website of the Future Foundation for Swiss Travelers, version from October 12, 2011, accessed on October 7, 2014

- Rolf Wolfensberger: Homeless. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Carl Durheim's homeless portraits in the online access of the Swiss Federal Archives

Individual evidence

- ↑ Museum for Communication Bern: Media release on the exhibition “Wanted” from May 1 to August 23, 1998 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed October 7, 2014

- ↑ Huonker: External and Self-Images , pp. 4–5 and Meier / Wolfensberger: A home and yet none (see literature)

- ↑ Huonker: External and Self-Images , p. 4 (see literature)

- ↑ Wolfensberger: Homeless (see web links)

- ^ Report of the Federal Commission of Inquiry, 1826. Quoted from Johann Conrad Vögelin: About the homeless and the duty of their care and naturalization. Ch. Beyel, Frauenfeld 1838, pp. 17–18 ( digitized from Google Books )

- ↑ Federal Law on Homelessness of December 3, 1850 , Federal Gazette 3 (1850), pp. 913–921 ( digitized version of the Swiss Federal Archives)

- ↑ Report of the Federal Council to the Federal Assembly on the Law on Homelessness , Federal Gazette 3 (1850), p. 124 ( digitized version of the Swiss Federal Archives)

- ↑ Report of the Federal Council to the Federal Assembly on the Law on Homelessness , Federal Gazette 3 (1850), p. 125 ( digitized version of the Swiss Federal Archives)

- ↑ Huonker: External and Self-Images , p. 6 (see literature)

- ↑ Federal Law on Homelessness of December 3, 1850 , Federal Gazette 3 (1850), Art. 19, p. 919 ( digitized version of the Swiss Federal Archives)

- ↑ Wolfensberger: Homeless (see web link)

- ↑ Annual report of the Federal Advocate General on his administration during 1852 , Federal Gazette 2 (1853), p. 716 ( digitized version of the Swiss Federal Archives)

- ↑ Gasser / Meier / Wolfensberger: Against denial and misrepresentation (see literature), p. 16

- ↑ Gasser / Meier / Wolfensberger: Against denial and misrepresentation (see literature), p. 12

- ↑ Gasser / Meier / Wolfensberger: Against denial and misrepresentation (see literature), pp. 137-138

- ^ Gasser / Meier / Wolfensberger: Against denial and misrepresentation (see literature), pp. 12-13

- ↑ Gasser / Meier / Wolfensberger: Against denial and misrepresentation (see literature), p. 15

- ↑ Annual report of the Federal Advocate General on his administration during 1852 , Federal Gazette 2 (1853), p. 717 ( digitized version of the Swiss Federal Archives)

- ^ Gasser / Meier / Wolfensberger: Against denial and misrepresentation (see literature), pp. 16-17

- ↑ The English author Edward Bradley wrote a humorous contribution under his pseudonym Cuthbert Bede: Photographic pleasures. Popularly portrayed with pen & pencil. T. Mc Lean, London 1855, pp. 69ff. ( Digitized from Google Books )

- ↑ Jens Jäger: Photography: a means of surveillance? Judicial photography, 1850 to 1900. In: Crime, History and Society 5 (2001), p. 31