Chinese banking

The Chinese banking system , by which one understands the trading of money and credit transactions in the general sense, is deeply rooted in the history of China.

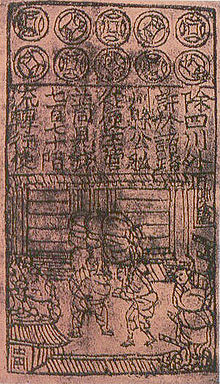

The introduction of paper money as a substitute means of payment in 1024 came earlier than anywhere else in the world. Furthermore, the monasteries in the 5th century are counted among the oldest credit institutions in China. As early as the Song Dynasty (960–1279), the Chinese financial institutions fulfilled all the important functions of a bank. These included, among other things, raising capital (deposit business), granting loans, issuing banknotes, currency exchange transactions and long-distance transfers.

Early banking age

The most important domestic banking institutions included Piaohao on the one hand and Qianzhuang on the other. Its development and that of foreign banks in the middle of the Qing Dynasty accelerated commercialization and ushered in a new high point of banking in China.

Piaohao

One of the earliest banking institutions in China was the Piaohao. This was also known as Shanxi Bank, as a large part of the banks were owned by residents of Shanxi Province . The first Piaohao emerged from the Xiyuecheng Dye Company, which was located in Pingyao County, Shanxi Province. The company developed a concept with which transactions between the individual branches could be carried out without much effort. Although this innovation was originally developed only for businesses within the Xiyuecheng Company, it achieved a very high level of awareness in a short time. For this reason, the owner of the company restructured his company, which specialized in this particular type of transfers, in 1823 and changed the name of the company to Rishengchang Piaohao. Over the next 30 years, 11 Piaohao were established in Shanxi Province. By the end of the 19th century, the company had expanded to a total of 32 Piaohao with 475 branches in all 18 provinces of China.

One of the main tasks of the Piaohao was cross-provincial remittances; and in the years after 1860 also participation in government affairs. Individual provinces in China had to transfer part of their tax revenues, which were also called jingxiang, directly to the capital Beijing . However, communication between the government and some of these provinces was cut off by the Taiping Rising . Deliveries from the jingxiang became increasingly rare until the government hired the Piahao to transfer taxes. This gave the bank the authority to broker foreign loans to the state government.

In the years after 1890, the Piaohao's financial strength was estimated at $ 280 million.

Qianzhuang

In addition to the Piaohao, there were a large number of smaller local banks; the so-called Qianzhuang. In the beginning, most of these financial institutions were located in Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces, or in the cities of Shanghai , Shaoxing and Ningbo . In contrast to the Piaohao, they were based locally and acted as commercial banks, where they took care of the local exchange of money, among other things. In 1890 there were about 10,000 qianzhuang in all of China .

Entry of foreign banks

With the growth of Western trading companies in the mid-nineteenth century, the first foreign banks settled in China. The Chinese described this with the term yinhang ( Chinese 銀行 ), which means something like "silver institution" and stands for the word "bank". Above all, the British Oriental Bank went in the 1840s, which was represented in Hong Kong , Guangzhou and Shanghai . This was followed by other British banks. The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, today HSBC , which was founded in Hong Kong in 1865, grew to become the largest foreign bank in China.

In this way, a quasi-monopoly prevailed for 40 years, which was advantageous for the British , until other European banks were added in the early 1890s and became competitors. These included the German-Asian Bank , Japan's Yokohama Specie Bank , France's Banque de L'Indochine and Russia's Russo-Asiatic Bank. In 1894, foreign banks made up 32% of the capital market. At the end of the nineteenth century there were 9 foreign banks with 45 branches in China's contract ports.

Because of the so-called unequal contracts , the foreign banks enjoyed numerous privileges, such as: B. Trade advantages, right of establishment, right to extraterritoriality and consular jurisdiction , as well as full control over China's international remittances and foreign trade finance .

State banks

After the self-empowerment movement began in 1861, aimed at modernizing China, the Qing government initiated major industrial projects. This required an enormous amount of capital, which could not be covered by the loans of the domestic financial institutions. In order to secure sufficient, long-term financing, China turned to the foreign banks. The Chinese government was also forced to do so because of the numerous military defeats during this time and the resulting compensation payments.

However, the foreign banks were not interested in investing in the country's long-term development. So it came about that in 1897 the first modern bank in China, the Imperial Bank of China, was founded as a stock corporation in Shanghai . The internal structure was based on the example of HSBC . The division heads were foreign specialists. After the proclamation of the Republic of China in 1912, the bank changed its English name to Commercial Bank of China , which should remove any reference to the Qing Dynasty .

The oldest bank in China still in existence today, the Bank of the Board of Revenue, opened in 1905. It was later renamed the Great Qing Government Bank or also known as the Daqing Bank. This was also re-established as the Bank of China in 1912 and also served as the first central bank in China. The government attributed many privileges and important roles to the BoC , including: a. issuing banknotes (until 1942), keeping the treasury and overseeing foreign credits. However, central bank status was given to the Central Bank of China in 1928 . Nevertheless, BoC is one of the big four banks in China (“big four”). These also include the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), China Construction Bank (CCB) and Agricultural Bank of China (ABC).

Private banks

The first private bank, the Chinese Bank of Commerce , was founded in 1897 by entrepreneur Shen Xuanhui . Three more emerged during the Qing Dynasty . From 1906 to 1908, the Xincheng Bank in Shanghai, the National Commercial Bank in Hangzhou and the Ningbo Commercial and Savings Bank were successively founded.

In addition, so-called southern and northern banks emerged at this time. The southern ones, based in Shanghai, included the Shanghai Commercial and Savings Bank , the National Commercial Bank, and the Zhejiang Industrial Bank . The northern ones included the Yien Yieh Commercial Ban, the Kincheng Banking Corporatio , the Continental Ban, and the China & South Sea Ban .

In April 1995, Minsheng Bank , the first fully private bank in the People's Republic of China, was established.

The golden age of Chinese banking

The period from 1928, the end of the Northern Expedition , to 1937, the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War , is now referred to as the golden decade. Because it initiated the modernization of China and the Chinese banking system.

The government established the Central Bank of China in 1928 , with Song Ziwen as president. The new central bank would specialize in international brokerage, while the Bank of Communications was focused on industrial development.

From 1949

Pre-reform period (1949 to 1978)

In 1949, the Communist Party , or CCP for short, came to power in China. The area of finance and banking was also built up by 1979 through the centralization and nationalization strategy, similar to the Soviet model. The foreign banks were gradually ousted from China during this period; all banks that were said to have ties to the Kuomintang were either closed or incorporated into the People's Bank of China (PBoC). The Chinese People's Bank (PBoC) is a merger of the Beihai, Huabei and Xibei Peasant Bank; it was established on December 1, 1948 in Hebei Province. It also took on the role of a central and commercial bank in the mono banking system of the People's Republic of China . The tasks of the PBoC included, among other things, the administration of the accounts of the Ministry of Finance, the control of the supply of money, the issuing of cash as well as the setting of interest rates on loans and savings. At the business policy level, she took care of the execution of payment transactions, the issuance of bonds and the administration of savings. Until 1970 the PBoC was directly subordinate to the State Council. One level below the State Council was the Ministry of Finance (MOF). From 1970 to 1978, both setting the state budget and controlling the PBoC fell within the remit of the MOF. As a result, the PBoC was dependent on government policies and goals. It could therefore also be compared with an executive state organ. In addition to the PBoC, the Bank of China , which was originally founded in 1912 and was responsible for “transferring money abroad”, the Agricultural Bank of China , existed as specialist banks ; first in 1955, but without success, then launched again in 1964. In addition, the People's Construction Bank was set up in 1954 for infrastructure projects.

Reforms from 1979

As a result of the eleventh congress of the Communist Party of China, the introduction of the “Four Transformations and Eight Reforms” and in the course of the reform and opening-up policy , a decentralization of the financial sector was sought. For this reason, China began the first reforms in 1979, in which the PBoC was separated from the Ministry of Finance (MoF) and shortly afterwards with the spin-off of the specialist banks, the ABoC, the BoC and the PCB. For the conversion of the PBoC into a central bank (around 1984), the commercial banking functions were divided between four state-owned specialist banks. These included the Industrial and Commercial Bank (ICBC), which was responsible for “financing the industrial sector”, the Agricultural Bank of China (ABoC) for agriculture, and the Bank of China (BoC) for export financing and foreign exchange trading and the China Construction Bank (CCB), which was responsible for the construction industry and infrastructure. The main responsibilities of the PBoC now included financial supervision and monetary policy.

The first steps towards a two-tier banking system and away from the previous mono-banking system were thus taken. In addition, this stimulated the formation of regional, local and national banks that were neither entirely state-owned nor directly privately owned. However, the PBoC was still subject to the State Council.

1995 to 1997

In the 1995 law for commercial banks (“Law of the People's Republic of China on Commercial Banks”) the role of the PBoC as a central bank and its status as a central bank was defined. The aim of this law was to reduce the influence of political institutions on the central bank, to promote the commercialization of commercial banks and to further promote the sovereignty of the PBoC. Furthermore, three economic policy banks were founded in 1994 to promote economic development:

- The State Development Bank, which among other things took care of the financing of infrastructure projects;

- The Agricultural Development Bank; responsible for rural areas and the fight against poverty as well

- The Import-Export Bank of China; responsible for promoting exports.

From 1997

As a result of the 1997 Asian crisis , it could not be denied that the Chinese banking sector was marked by “a lack of transparency, inadequate control mechanisms, poor risk management and corruption”. Supervisory and monetary tasks should therefore be separated more clearly. For this reason, various supervisory tasks of the PBoC, such as supervisory powers with regard to insurance companies, securities companies and credit institutions, have been distributed to other banks.

In order to limit the interference of local governments to a minimum and so that the PBoC could better implement its role as central bank, the previous 31 branches of the bank were reduced to 9. This resulted in a larger area of responsibility for the individual branches, even beyond provincial borders.

In conclusion, it can be said that the Chinese banking system has fundamentally changed. Particularly between 1949 and 1997, clear changes can be seen; the former mono-banking system has developed into a variety of banks in which commercial and political banking are separated from each other.

literature

- Brunhild Staiger, Stefan Friedrich, Hans-Wilm Schütte: The great China Lexicon . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2003

- Daibei Huang: The Chinese banking sector under the sign of WTO accession - Reform backlogs and challenges . Ed .: Prof. Dr. HH Bass, Prof. Dr. K. Wohlmuth. Bremen 2002

- Dr. Angiolo Laviziano, Ph.D .: Benchmarking of the Commercial Banking System in PR China. Paul Haupt, Bern / Stuttgart / Vienna 2001

- Hans Janssen van Doorn: Modernization of Chinese banking market: A concise history since 1911, How did China's political development influence the development of the China's Banking System? Tilburg University, Tilburg 2011

- Kui-Wai Li: Financial Repression and Economic Reform in China. Praeger, Westport 1994

- Linsun Cheng: Banking in Modern China, Entrepreneurs, Professional Managers and the Development of Chinese Banks Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003

- Melina Herr: Developments and tendencies of domestic and foreign banks in China after joining the World Trade Organization . WiKu, Stuttgart / Berlin 2004

- Stephan Popp: Multinational banks in the future market PR China: Success factors and competitive strategies. Gabler, Wiesbaden 1996

further reading

- Catherine Somé: A history of modern Shanghai banking: the rise and decline of China's finance capitalism. Armonk, New York 2003

- Cecil R. Dipchand, Yijun Zhang, Mingjia Ma: The Chinese financial system. Greenwood Press, Westport (Connecticut) 1994

- Henry Sanderson, Michael Forsythe: China's Superbank; Debt Oil and Influence - How China Development Bank is Rewriting the Rules of Finance. Bloomberg Press, 2013

- Stephen Bell, Hui Feng: The rise of the People's Bank of China: the politics of institutional change. Harvard University Press, Cambridge / London 2013

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Linsun Cheng: Banking in Modern China, Entrepreneurs, Professional Managers and the Development of Chinese Banks . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, pp. 10-11 .

- ↑ Linsun Cheng: Banking in Modern China, Entrepreneurs, Professional Managers and the Development of Chinese Banks . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, pp. 11 .

- ↑ Linsun Cheng: Banking in Modern China, Entrepreneurs, Professional Managers and the Development of Chinese Banks . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, pp. 11-14 .

- ↑ Linsun Cheng: Banking in Modern China, Entrepreneurs, Professional Managers and the Development of Chinese Banks . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, pp. 14-15 .

- ^ A b History of Banking in China : Entry of Foreign Banks. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on March 16, 2016 ; accessed on January 29, 2017 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Hans Janssen van Doorn: Modernization of Chinese banking market: A concise history since 1911, How did China's political development influence the development of the China's banking system? Tilburg University, Tilburg 2011, p. 7 .

- ^ A b c History of Banking in China: Government Banks. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on January 29, 2017 ; accessed on January 29, 2017 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Hans Janssen van Doorn: Modernization of Chinese banking market: A concise history since 1911, How did China's political development influence the development of the China's banking system? Tilburg University, Tilburg 2011, p. 8 .

- ↑ Bank of China Overview. Retrieved January 29, 2017 .

- ^ The changing Chinese banking system. Retrieved January 29, 2017 .

- ^ Hubert Bonin: Asian Imperial Banking History. Routledge, July 28, 2015, accessed January 29, 2017 .

- ^ A b History of Banking in China: Private Banks & Golden Age of Chinese Banking. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on January 29, 2017 ; accessed on January 29, 2017 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Daibei Huang: The Chinese banking sector under the sign of WTO accession - Reform backlogs and challenges . Ed .: Prof. Dr. HH Bass, Prof. Dr. K. Wohlmuth. Bremen 2002, p. 13 .

- ↑ Stephan Popp: Multinational banks in the future market PR China: Success factors and competitive strategies . Gabler, Wiesbaden 1996, p. 29 .

- ↑ Dr. Angiolo Laviziano, Ph.D .: Benchmarking of the Commercial Banking System in PR China . Paul Haupt, Bern / Stuttgart / Vienna 2001, p. 13-14 .

- ^ Stephan Popp: Multinational banks in the future market PR China . Gabler, Wiesbaden 1996, p. 29-31 .

- ↑ Daiwei Huang: The Chinese banking sector in the sign of WTO accession - Reform residues and challenges . Ed .: Prof. Dr. HH Bass, Prof. Dr. K. Wohlmuth ,. Bremen 2002, p. 4 .

- ^ A b Melina Herr: Developments and tendencies of domestic and foreign banks in China after joining the World Trade Organization . WiKu, Stuttgart / Berlin 2004, p. 23 .

- ^ Kui-Wai Li: Financial Repression and Economic Reform in China . Praeger, Westport 1994, p. 31 .

- ↑ Melina Herr: Developments and tendencies of domestic and foreign banks in China after joining the World Trade Organization . WiKu, Stuttgart / Berlin 2004, p. 23-24 .

- ↑ Melina Herr: Developments and tendencies of domestic and foreign banks in China after joining the World Trade Organization . WiKu, Stuttgart / Berlin 2004, p. 24 .

- ^ Brunhild Staiger, Stefan Friedrich, Hans-Wilm Schütte: The great China Lexicon . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2003, p. 68 .

- ↑ Melina Herr: Developments and tendencies of domestic and foreign banks in China after joining the World Trade Organization . WiKu, Stuttgart / Berlin 2004, p. 24 .

- ↑ Daiwei Huang: The Chinese banking sector in the sign of WTO accession - Reform residues and challenges . Ed .: Prof. Dr. HH Bass, Prof. Dr. K. Wohlmuth. Bremen, S. 11-12 .

- ^ Brunhild Staiger, Stefan Friedrich, Hans-Wilm Schütte: The great China Lexicon . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt, p. 68 .

- ↑ Daiwei Huang: The Chinese banking sector in the sign of WTO accession - Reform residues and challenges . Ed .: Prof. Dr. HH Bass, Prof. Dr. K. Wohlmuth. Bremen, S. 14-15 .