The boy from El Plomo

The boy from El Plomo is a permafrost corpse from an Inca high sanctuary in the Andes near Santiago de Chile . The eight-year-old child was buried alive around 1500 AD on a 5400 m high peak of the El Plomo massif in order to provide protection for the valley in mediation with the supernatural and to consolidate the political and economic power of the Inca ruler. Excavated by looters in 1954 and sold to the local natural history museum, it was the first child sacrifice of a Capacocha ritual to be scientifically investigated. The religious veneration that was bestowed on the boy has been preserved in archaic rites up to the present day.

description

The boy from El Plomo is the name given to the extremely well-preserved permafrost corpse of an eight-year-old Inca boy. It was discovered on February 1, 1954. He was 1.40 to 1.44 m tall and weighed just over 30 kg when he died. He was normally trained, outwardly apparently healthy and had no fatal injuries.

The boy assumes a sitting posture with his knees raised and legs crossed. His head rests on his knees, which he embraces with his arms. Overall, it is inclined slightly to the right. He was a Unku (short tunic) of black llama wool clothed, sometimes 94 cm in size, decorated 47 front and rear with four horizontally arranged strips of white llama fur and down with a red trim. Around his shoulders he wore a yacolla (cape), 119 by 70 cm, made of gray alpaca wool. On his feet he had a pair of unused hisscu ( moccasins ), each made from a piece of leather. According to the custom for children, he did not wear underwear. On his right forearm he wore a 12 cm wide silver bracelet.

The black, strong hair, neatly coiffed with more than 200 fine braids and divided by a center parting, extends backwards and downwards to over the shoulders. On his head he wore jewelry made of wool with black wool fringes and attached white and black condor feathers .

He wore a llauto (headband) with a chin strap, braided in a piece of black human hair. Attached to it was a silver plaque in the shape of a lying H. The silver plaque is 17.7 cm wide, 6.8 cm high and 2 mm thick.

The boy's eyes are closed. He has relatively long, straight eyelashes and bushy eyebrows. His face is made up with red paint of iron oxide with fat and with yellow stripes that converge diagonally to the nose and mouth.

When he was found, his body was still soft, like someone who had recently passed away. Afterwards, due to the transport to a warmer and also dry climate zone, a natural mummification set in and the body became almost rock hard on the surface.

His blood type was A. His skull was somewhat deformed through long use of the Llauto . He had head lice eggs in his hair . His skin has scars from skin diseases such as acne or furunculosis and an angiokeratoma . Eight ulcer-like injuries were found on the legs. The feet have a pronounced keratinization of the skin. The thumb and forefinger of the right hand have small warts . It was heavily infested with trichinae , which, according to previous epidemiological findings, had been introduced from China around 1000 AD.

Tomb and ceremonial complex

The boy was found on the summit of Cerro El Plomo . The dominant mountain, visible from afar, with its mostly snow-free summit ( 33 ° 14 ′ S , 70 ° 13 ′ W ) at 5424 m above sea level is about 46 km as the crow flies northeast of the center of Santiago . In the late 15th and early 16th centuries, the region belonged to the southernmost rule of the Inca Empire Tawantinsuyu with an administrative center at today's Plaza de Armas in Santiago.

The tomb, called Enterratorio in Spanish , was a multi-part system on a secondary peak, the ruins of which are located at 33 ° 14 ′ S , 70 ° 13 ′ W around 300 m west of the main peak. It consisted of three rectangles of different sizes enclosed by dry stone walls. The boy's grave was the largest of the three, around 3.5 m long and 1.8 m wide. The wall thicknesses were 60 to 70 cm. The stones of different sizes with a maximum weight of 25 kg were unprocessed, sharp-edged and stacked up to 80 cm high in the simplest way. The areas between the inner walls were completely filled up to the top of the wall with a mixture of soil, straw and hay, as well as three to four horizontally arranged thin layers of small rounded stones. These materials do not come from the same mountain and have certainly been brought from another place. As a result of continued looting, most of the filling material had already been excavated in 1954 and the walls were largely destroyed. In each of the three rectangles there is a round pit in the permafrost , all of a similar size. The one in which the boy was buried is embedded in the underground rock. Measured from the surface of the filling material, it is 1.3 to 1.4 m deep. At the level of the permafrost it has a diameter of 80 cm and was closed with a stone slab to form a crypt. It has been suggested that one of the other two pits was also a grave. The fact that no more corpses were found, as in other places, may also be due to the fact that the Inca only ruled the region for a relatively short time, almost 50 years.

From the grave you can see far into the surroundings and vice versa it is visible from far away places. The Aconcagua can be seen in 68 km to the north and the Peladero in 50 km to the south ( 33 ° 41 ′ S , 70 ° 13 ′ W ). Both mountains with mythical significance, on which Inca ruins have also been found. To the southwest, the Mapocho Valley with Santiago can be seen and to the west, at least 135 km away, the Pacific Ocean can be seen.

A cult site is located southeast of the burial site, within sight, approx. 650 m away and 200 meters lower down. ( 33 ° 15 ′ S , 70 ° 13 ′ W ) It consists of a platform with an incorporated ushnu (place for receiving liquid offerings) and is generally referred to as adoratorio (Spanish for place of worship). Unlike the other constructions on the mountain, it has an oval shape. An outer ring-shaped stone wall covers an area with 9 m or 8.5 m in its main axes, around 60 m² in size. An inner stone wall concentric to it has 2.1 m and 1.7 m in the axes. The space between the walls was filled with stones up to the top of the wall. The bottom of the inner wall ring is laid out with flat stones. There was a fireplace in front of the platform. The long axis of this complex and the main axis of the grave above form a line with a 13 ° deviation from north to west. From the place of worship you have a clear view of the Iver Glacier to the burial site.

On the way from the valley to the summit of El Plomo there are a number of facilities and a paved path. Modern mountaineers set up their base camp in the easily accessible Piedra Numerada ( 33 ° 17 ′ S , 70 ° 13 ′ W ), a valley plain with grassland on the Río Cepo, which is 6 km south of the summit at an altitude of 3400 m and 4 km north of the Valle Nevado ski center in Santiaguin. On the way to this base camp there are two walls at Estero Las Llaretas. Around Piedra Numerada there are six other systems that are attached to the rocks. One of them, like the Adoratorio cult site, is elliptical with a hole and with a view of the summit of El Plomo. At the El Plomo west ridge, already at an altitude of over 5000 m, a path paved with flat stones leads towards Adoratorio . In the immediate vicinity of the Adoratorio , on the beginning of the western slope, there is a group of five stone huts on terraces that offer space for 20 to 30 people.

Sacrifice in the Capacocha ritual

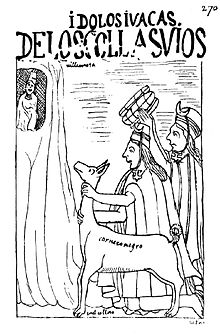

In Inca mythology, mountains were gods ( Apu ) who gave or took life through the control of natural phenomena. In a ceremonial ritual called Capacocha , selected objects or animals were offered as sacrifices to the sacred mountains that were worshiped . Children were also killed on special occasions. Spread over the former Inca empire there are 192 mountains on which ceremonial complexes have been found. On 14 mountains, all but one of which are over 5400 m high, a total of 27 Capacocha human victims were found between 1896 and 1999, with one exception all children. There are also human sacrifices from two islands. In the theocratic Inca state, the Capacocha was one of the most important rituals. It was not only religiously motivated, it was rather a rite of the state, with which the geography and politics of the empire were defined and the political and economic power of the Inca was consolidated. The sacrifice of the boy from El Plomo as part of a Capacocha occurred after 1483 when the Inca began to incorporate central Chile into their empire, and before 1533 when the Spanish took the Inca capital of Cuzco . "The boy from Aconcagua", another permafrost corpse, found 70 km further north on Aconcagua , was sacrificed in the same period, possibly even at the same time.

To hold a Capacocha , messengers were sent by the Inca rulers who demanded tributes in the country's provinces. Requests were made for boys and girls between the ages of four and ten as well as objects made of gold, silver or shells and fine clothing, feathers, coca leaves and camelids. The children had to be physically perfect, flawless and virgin. Judging by his clothes, the boy from El Plomo came from Qulla Suyu, the southern province of the Inca Empire. He most likely belonged to the Kolla people, the most powerful ethnic group of this province in the Bolivian Altiplano . There is evidence that a boy named Cauri Pacssa was brought to Chile as a human sacrifice. It is not clear whether it was he who was found on El Plomo.

When the tribute arrived in Cuzco, the Inca and his court received the dignitaries who had come with the Capacocha gifts with a ritual festival lasting several days. Together with his priests, the Inca determined which Huaca (mountain sanctuary) received which sacrifice. After completing all formal preparations, the priests left Cuzco with the entourage and the offerings in a solemn procession along the prescribed routes. The Capacocha procession went on foot along the Inca Trail from Cuzco to the city that is now called Santiago. Cuzco and El Plomo are 2193 km apart as the crow flies. The procession was received and escorted in the provinces by representatives of local princes.

In the twelve months before the sacrifice, the boy was fed special meals such as corn and charqui so well that he ended up being overweight. As the thick layers of callus on the soles of his feet suggest, he went barefoot. When he arrived in Santiago he was eight years and three months old.

At El Plomo there was a ritual meal 24 hours before death. From the Adoratorio the boy had to walk hundreds of meters to the Enterratorio . This is the most difficult and dangerous part of the route, even today, because the route leads over the Iver Glacier. Presumably, he developed a noticeable edema on his right foot.

On Enterratorio he had arrived safely exhausted from the arduous journey in the thin mountain air. He chewed coca leaves and was given chicha to drink. Exhausted and numbed by alcohol and other drugs by the priests , he became tired. The body struggled one last time and tried to vomit up the poison. The boy sat down in the prepared hole. To protect himself from the cold, he pulled his tunic over his bent knees to his feet and wrapped his arms around his legs. The boy gradually fell asleep and his head sank to his knees. The priests furnished him with grave goods and then buried him asleep, still alive, by closing the crypt with a stone and covering it with earth. The boy soon died of hypothermia and lack of oxygen before freezing.

Mythical meaning to the present day

As late as 1620, almost a century after the beginning of the Spanish colonization and Christianization , it was registered that the indigenous population remembered their Capacocha children and the location of their graves and continued to worship them with their rituals.

When the discovery of the boy from El Plomo became known, the locals from the area of San Pedro de Atacama spoke of the fact that he was the legitimate son of the Licancabur and Quimal mountains . These two mountains of mythical importance are characterized by the fact that they cast shadows alternately on the other mountain around the time of the southern summer solstice in the morning and in the evening.

The boy from El Plomo still takes his place in the mythology of the indigenous population up to the present day as the “chief guardian” or “guardian child” of the mountain god El Plomo. People who see themselves as descendants of the peoples of the Inca state Tawantinsuyo gather on June 21st for Inti Raymi , the winter solstice and New Year celebrations, and worship Inti Wawa , the child of the sun. One such event has been held in front of the Natural History Museum in Santiago every year since 2009. On this occasion, the museum allowed participants to view the boy's body.

See also

- Cult around the boy from El Plomo : Video from the Inti Raymi festival in Santiago de Chile .

Remarks

- ↑ Since its discovery, the corpse has been given a number of names that have been discarded over time. The one used here corresponds to the translation of the term "Niño del Cerro El Plomo" used recently by Spanish-speaking scientists.

- ↑ Estimated location and altitude according to Google Maps 2013, taking into account the map by Luis Krahl Tafelmaier.

- ↑ Also written capac hucha, qhapaq hucha or qhapaqcocha .

- ↑ These include: Aymara , Quechua , Likan Antay , Kolla , Diaguita .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Grete Mostny et al .: La Momia del Cerro El Plomo . In: Boletin del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural . tape XXVII , no. 1 . Santiago de Chile 1957 ( dibam.cl [PDF; accessed December 10, 2013]).

- ^ Niño del Cerro El Plomo: Una valiosa pieza antropológica. (No longer available online.) Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Chile, June 18, 2012, archived from the original on February 1, 2014 ; Retrieved December 30, 2013 (Spanish). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Alvaro Sanhueza S., Lizbet Pérez M., Jorge Díaz J., David Busel M., Mario Castro, Alejandro Pierola T .: Paleoradiología. Estudio imagenológico del Niño del Cerro El Plomo . In: Revista Chilena de Radiología . tape 11 , no. 4 , 2005, p. 184–190 ( scielo.cl [PDF; accessed December 31, 2013]).

- ↑ a b Mario Castro: El niño del plomo revive en TVN . In: El Mercurio . November 28, 2009 ( buscador.emol.com [accessed December 31, 2013]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g Héctor Rodríguez, Isabel Noemí, José Luis Cerva, Omar Espinoza-Navarro, María Eugenia Castro, Mario Castro: Análisis paleoparasitológico de la musculatura esquelética de la momia del Cerro el Plomo, Chile: Trichinella Sp. In : Chungara Revista de Antropología Chilena . tape 43 , no. 1 , 2011, ISSN 0716-1182 , p. 581-588 , doi : 10.4067 / S0717-73562011000300013 ( PDF [accessed February 5, 2019]).

- ↑ a b c d Fidel Jeldes: Estudio somatométrico, Protocolo antropológico sobre el niño indígena del Plomo . In: Grete Mostny (ed.): Boletin del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural. La Momia del Cerro El Plomo . tape XXVII , no. 1 . Santiago de Chile 1957, p. 17-19 ( dibam.cl [PDF; accessed December 10, 2013]).

- ↑ a b c d e Patrik D. Horne, Silvia Quevedo Kawasaki: The prince of El Plomo: A paleopathological study . In: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine . tape 60 , p. 925-931 , PMC 1911799 (free full text).

- ^ Luis Prunes: Estudio medico . In: Grete Mostny (ed.): Boletin del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural. La Momia del Cerro El Plomo . tape XXVII , no. 1 . Santiago de Chile 1957, p. 19–20 ( dibam.cl [PDF; accessed December 10, 2013]).

- ↑ Patricio Bustamante Díaz, Ricardo Moyano: Cerro Wanguelen. obras rupestres, observatorio astronómico-orográfico Mapuche-Inca and the sistema de ceques de la cuenca de Santiago. In: Rupestreweb. 2013, accessed January 13, 2014 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Luis Krahl: El cerro El Plomo. Construcciones precolumbinas . In: Grete Mostny (ed.): Boletin del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural. La Momia del Cerro El Plomo . tape XXVII , no. 1 . Santiago de Chile 1957, p. 85–95 ( dibam.cl [PDF; accessed December 10, 2013]).

- ↑ a b c d e f Quevedo K. Silvia, Durán S. Eliana: Ofrendas a los dioses en las montañas. Santuarios de altura en la cultura Inca . In: Boletin Museo Nacional de Historica Natural Chile . tape 43 , 1992, ISSN 0027-3910 , pp. 193–206 ( dibam.cl [PDF; accessed December 21, 2013]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Coordinates, heights and distances determined with Google Earth, 2013.

- ↑ According to the maps from the IGM

- ^ A b Rubén Stehberg, Gonzalo Sotomayor: Mapocho incaico . In: Boletín del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Chile . tape 61 , 2012, p. 85–149 ( academia.edu [PDF; accessed December 31, 2013]).

- ↑ Ricardo Candia: Tambo en la ruta del Qhapaqcocha. March 25, 2010, accessed January 15, 2014 (Spanish).

- ↑ a b c d Christian Vitry: Los espacios rituales en las montañas donde los inkas practicaron sacrificios humanos . In: Carlos Terra, Rubens Andrade (eds.): Paisagens Culturais. Contrastes sul-americanos . Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. Escola de Belas Artes, 2008, p. 47–65 ( christianvitry.com [PDF; accessed December 21, 2013]). christianvitry.com ( Memento of the original dated February 2, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c d e Tamara L. Bray, Leah D. Minc, Marıá Constanza Ceruti, José Antonio Chávez, Ruddy Perea, Johan Reinhard: A compositional analysis of pottery vessels associated with the Inca ritual of capacocha . In: Journal of Anthropological Archeology . tape 24 , 2005, pp. 82–100 , doi : 10.1016 / j.jaa.2004.11.001 ( researchgate.net [PDF; accessed December 30, 2013]).

- ↑ Jennifer L. Faux: Hail the Conquering Gods. Ritual Sacrifice of Children in Inca Society . In: Journal of contemporary anthropology . tape 3 , no. 1 , 2012, ISSN 2150-3311 , p. 2-15 ( docs.lib.purdue.edu [accessed December 30, 2013]).

- ↑ Cauri Pacssa ¿El niño del cerro El Plomo? Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, archived from the original on February 1, 2014 ; accessed on January 15, 2014 .

- ↑ a b Annette Schroedl: La Capacocha como ritual político. Negociaciones en torno al poder entre Cuzco y los curacas . In: Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Études Andines . tape 37 , no. 1 , 2008, p. 19–27 ( online [PDF; accessed January 13, 2014]).

- ^ María del Carmen Martín Rubio: La cosmovisión religiosa andina y el rito de la Capacocha . In: Investigaciones Sociales . tape 13 , no. 23 , 2009, p. 187–201 ( sisbib.unmsm.edu.pe [PDF; accessed January 4, 2014]).

- ↑ Gustavo Le Paige: Vestigios arqueológicos incaicos en las cumbres de la zona atacameña . In: Estudios Atacameños . No. 6 , 1978, p. 37–48 ( Vestigios arqueológicos incaicos en las cumbres de la zona atacameña ( Memento from February 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) [PDF; accessed December 14, 2013]). Vestigios arqueológicos incaicos en las cumbres de la zona atacameña ( Memento of the original from February 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Homenaje de pueblos originarios al niño del cerro El Plomo. Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, archived from the original on February 2, 2014 ; accessed on January 15, 2014 .

- ↑ groups.google.com

- ↑ lagranepoca.com ( Memento of the original from February 23, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ mnhn.cl ( Memento of the original from February 1, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ A b Ricardo Candia: Inti Raymi. Celebramos el año nuevo de los pueblos indígenas este 21 de junio con una ceremonia de veneración y reencuentro con el niño del Altar Mayor del Apu “El Plomo”. June 21, 2009, accessed January 15, 2014 .