Skull manipulation among indigenous peoples of Latin America

The skull manipulation in indigenous peoples of Latin America is the kind of artificial influence on the skull that when indigenous peoples of South America and indigenous peoples of Central America was observed. Skull manipulation includes artificial skull deformations and skull openings, which occurred in particular among the Maya , Inca and Aztecs and other indigenous peoples of Latin America and are in some cases still practiced today. In the Peruvian Andes, skull deformation was mainly carried out using compression bandages, but also often in combination with occipital boards. Skull openings (also called trepanations) were mainly practiced by the Paracas culture , Chimú culture and Mesoamerican cultures, and artificial deformations came to light mainly in the Paracas, Nazca , Huari , Huanca , Aymara , Quechua , Tiahuanaco and Urus . The Paracas culture is believed to be one of the first cultures to perform skull openings in Latin America. In the south-central Andes, cranial openings were performed using a tumi, a metal ceremonial knife, among other things. One explanation for the artificial skull deformation is that this type of skull deformation served as a lifelong demonstration of belonging to a certain tribe . In certain regions, an elongated skull was seen as an ideal of beauty and served as a sign of belonging to a higher class, attractiveness and underlining ethnicity. Often artificially deformed skulls also show the Inca leg , which is a genetic variety. Some scientists attach clinical importance to this cranial bone because it could cause irregular bulges and indentations leading to skull deformation.

Skull operations on indigenous peoples of South America

overview

Trepanation has been practiced in a variety of historical cultures and communities around the globe. There is evidence that this was practiced even in the Neolithic Age . This practice continues to this day, but it is only practiced under very limited circumstances and in very few cultures. If the patient survived the procedure, the bone slowly began to grow back from the edge of the trepanation hole to the center. This new bone growth was measurably thinner than the undamaged bone, so scientists are examining trephined skulls to see whether the skull showed signs of healing or not. Among the indigenous peoples of South America, this treatment practice is most common in the Andean civilizations, such as the Inca, where it is often associated with the occurrence of skull deformation. However, trepanations were also carried out in pre-Inca cultures. According to John Verano , trepanation in ancient Peru is one of the greatest puzzles in medical history . There are no records of the indigenous peoples themselves, although so many perforated skulls have not been found in any other country in the world, and so have the Spaniards the skull openings in theirs not mentioned in early colonial reports. For Verano it is clear that the Inca were far superior to their conquerors in the art of skull opening.

South-central Andes

Trepanations appeared on a large scale in the south-central Andes for the first time around 200–600 AD and were later perfected by the Chimú culture, which is famous for its gold and metal products. During an initial examination of surgically opened skulls, the anthropologist Paul Broca (1824–1880) came to the conclusion that “advanced surgery” was practiced in ancient Peru. The skulls examined showed signs of healing processes at the bone margins, which was evidence that "successful" skull openings were performed, in which the patients survived. This type of skull opening was performed to eliminate physiological disturbances or skull fractures. The medicine men who opened the skull used a tumi , a metal ceremonial knife. The medicine man prepared the skull with the tumi, bleeded it to remove the disorder, and then covered the area with a gold plate. Not only the Tumi was used in the operations, but also bronze tools and fine copper needles. Every sixth skull the researchers examined had at least one trepanation hole. In the most extreme case, up to seven holes have been found in a skull, with many holes almost perfectly circular in shape. According to John Verano, there is one burial site where 50% of all men, 30% of all women and 30% of all youths have trepanation holes in their skulls. Very often found skulls show a high degree of deformity in addition to skull openings. The oldest skull found with a trepanation hole dates from around 400 BC. In ancient Peru, surgical skull opening was practiced much more frequently than in ancient Europe and was perfected by "Peruvian medicine men", which can be proven by the significantly high survival rate of the operated. At the time of the expansion of the Inca Empire, more than 90% of the patients survived. Archaeologists found skulls in which up to five trepanations had completely healed. A study published in 2018 reported skulls found in Incan archaeological sites that had successfully performed up to seven trepanations. Through the use of various substances for disinfection such as saponin , cinnamic acid and corilagin , the wound only became inflamed in 4.5 percent of cases (see also Inca medicine ). Today, many trephined skulls can be seen in the Museo Regional De Ica in Ica .

Mesoamerica

The prevalence among the Mesoamerican civilizations is much lower than that in the south-central Andes, at least relatively few trephined skulls were found. But also in Mesoamerica some skulls were found in which the individuals must have survived the operation. Archaeological analysis is difficult because many skulls were artificially altered after the person died. For example, in some cases additional holes were drilled in the skull after death and the skulls of prisoners and enemies were used as so-called “trophy skulls”. Its use as a trophy skull was a widespread tradition that was also reflected in pre-Columbian art. In artistic or ritual depictions, rulers are occasionally depicted with the modified skulls of their defeated enemies or victims. Some Mesoamerican cultures also used tzompantli , in which skulls were impaled in rows or columns on wooden stakes.

Central Mexico and Oaxaca

The earliest archaeological report was a report published in the journal American Anthropologist of trephined skulls of several specimens discovered in the Tarahumara Mountains by the Norwegian ethnologist Carl Sofus Lumholtz (Lumholtz & Hrdlička 1897). Later studies documented cases of trepanation in Oaxaca and central Mexico, as well as in specimens of the Zapotec civilization.

A 1999 study of seven trephined skulls from Monte Albán showed a combination of simple, multiple and elliptical trephination holes drilled into the top of the skull, more precisely into the upper parietal bones. The skull samples were from both male and female adult skulls, and evidence of healing indicated that approximately half had survived the operation. Most of the skulls in the study showed signs of previous damage, which (as with the Andean examples) indicated that these surgeries were attempts to repair or alleviate the head trauma that was already present. From these analyzes it appears that the earliest discoveries used a direct abrasion technique, which was later combined with drilling and incision techniques.

Maya region and Yucatan peninsula

The samples identified by the Mayan civilization region of southern Mexico, Guatemala and the Yucatan Peninsula show no evidence of the drilling or cutting techniques in central and highland Mexico. Instead, the pre-Columbian Maya appeared to have used an abrasive technique that removed the back of the skull, thinning the bone, and sometimes perforating it as well. Many of the skulls from the Maya region date from the post-classical period (approx. 950–1400) and contain specimens that were found near Palenque in Chiapas .

Skull deformations in indigenous peoples of Latin America

Explanatory approaches

Modern explanatory approaches suggest that this type of skull deformation should serve as a lifelong expression of belonging to a certain tribe . In particular, an elongated skull was viewed as an ideal of beauty and served as a sign of belonging to a higher class. In some cases, the deformation also served to increase the attractiveness and to underline the ethnicity. The triggering of the phenomenon by an abnormality, the genetic craniosynostosis , has also been considered. This is a premature ossification of one or more skull sutures. The normal growth of the skull is not possible and a compensatory growth with unusual skull shapes occurs.

Spread of the skull deformation

Artificial skull deformation was widespread in Latin America. When the conquistadors arrived in the New World in the 16th century , it was banned. Thus, the Inca were the last advanced civilization in South America to practice the technique of skull deformation. A cranial deformity was found in 87% of all prehistoric skulls in Peru and 89% in Chile. Both sexes were represented equally often. Deformation was also widely practiced in newborns among indigenous peoples of South America. Skull deformation in newborns was widespread across the American continent, but was most prevalent in the Andean regions, including Venezuela, Guyana, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina.

Effect on health

There is no statistically significant influence in cranial capacity between artificially deformed and normal skulls in samples of Peruvian skulls. Furthermore, no evidence of neurological impairment was found in indigenous groups who practiced cranial deformations in newborns. In a random test of artificially deformed male and female skulls, a deterioration in health could only be determined in the male, although it is questionable whether this is due to the artificial modification. Furthermore, a possible positive influence on the cognitive abilities that could be caused by the artificial skull deformation was discussed again and again. Whether the pressure caused by the compression bandages and affected certain areas of the skull had harmful, useful (positive effects on brain functions) or insignificant influences can only be determined theoretically, since the practice of skull deformation is almost no longer practiced today and thus one detailed investigation is excluded. In 2004 Francisco Javier Carod Artal investigated the connection between the occurrence of the Inca leg and the occurrence of artificial skull deformation in indigenous peoples of South America. He found that there is a significant correlation between the presence of posterior and lateral inca legs, depending on the degree of artificial deformation . The feature of the Inca leg , which he investigated , which represents an anatomical variation, was first described in 1851 by the naturalists Mariano Eduardo de Rivero y Ustáriz (1798–1857) and Johann Jakob von Tschudi (1818–1889) and by the surgeon P.F. Bellamy mentioned for the first time when analyzing the skulls of two Peruvian children's mummies. In a study published by Togersen in 1951 it was found that the Inca leg is inherited dominantly and has a penetrance of 50%. Artificial skull deformations have also been discussed as the cause (Ossenberg, 1970; Lahr, 1996), since Inca legs are often found in deformed brain skulls. Some scientists attribute clinical importance to the skull bone. Because of him, irregular bulges and indentations leading to skull deformation could arise.

Techniques and types of deformation

In the Peruvian Andes, skull deformation was mainly carried out using compression bandages , but also often in combination with occipital boards. The indigenous peoples of South America had an abundance of types of skull deformation, but these can be roughly condensed into different types of skull deformation. In 1930 the anthropologist José Imbelloni presented a classification of artificially deformed skulls, which is still widespread today. He suggested distinguishing between a circular shape, an oblique shape, and one of straight shape. Three basic forms can be roughly identified: Occipital , lambdoid and fronto-lambdoid deformation. Other authors prefer the classification: flattened on both sides, conical and cylindrical.

Skull deformation in ancient Peru and Bolivia

The pre-Inca artificially deformed skulls found in Peru and Bolivia show, in contrast to many other skulls found, a high degree of deformity. Skulls from the south coast of Peru are the least studied anthropologically. The few skulls examined in the Paracas necropolis are so badly deformed that they do not allow any conclusions to be drawn about the natural shape of the skull. The most impressive and famous are those of the Paracas culture, with many finds mainly related to burial sites, such as the archaeological sites of Chongos (Pisco Valley), Painted Mountain ( Cerro Colorado ) and Long Skulls ( Cabezas Largas on the Paracas peninsula ) , in Callango and in Ocucaje (in the Ica Valley ). Many of these skulls, which stand out for their artificial deformation, were examined by M. Tiedemann and given to many public and private museums. In 2003, Martin Friess and Michel Baylac examined samples of ancient Peruvian skulls using an elliptical Fourier analysis (EFA) and evaluated their results statistically. Their analysis indicated that the practice of skull deformation was subject to morphological trends in the population studied; H. In the course of time, the idea of a beautiful skull changed, which was then also reflected in practice.

Paracas culture

Origin of the Paracas culture

The archaeologist Julio Tello assumed that the Paracas was related to a pre-Inca culture, the Chavín culture (850–200 BC), which is more than 3000 years old. Tello himself led several excavations at Chavín de Huántar . For Tello, the Chavín culture represents a “mother culture” from which many other cultures emerged. Later cultures that followed the Paracas culture, such as the Tallán and Moche cultures (0–650 AD), also practiced trepanation and skull deformations. Elongated skulls are also depicted in Moche art and Moche pottery.

Discovery of the Paracas necropolis

In 1928, more than 300 deformed skulls were discovered by Julio Tello during excavations at a necropolis on the Paracas Peninsula, an area near the Nazca Lines . The first Paracas necropolis was found at Tello in the hills of Cerro Colorado. He found a total of 39 shaft graves , which he called "caves". The buried were wrapped in thin blankets and surrounded by ceramics, hunting tools, animal skins and food that were wrapped in grave bundles and enclosed. In 1927, Tello and Toribio Mejía Xesspe discovered another cemetery in Warikayan , near Cerro Colorado , with 429 mummies, some of them very well preserved, each wrapped in several layers (so-called mummy bundles). They were buried with the Paracas coats and can be seen today in the Museo Nacional de Arqueología Antropología e Historia del Perú . The mummies show trepanations and striking skull deformations . Tello finally discovered a third cemetery on the Paracas Peninsula, which was also called "long skull" because of the deformed skulls found there. He also found remains of underground dwellings next to plundered graves. Many valuable ceramic pieces, textiles and grave bundles can be viewed in Lima , in the Museo Herrera Larco , in the Museo De La Nación En La Ciudad De Lima and in the city of Paracas, in the Museo Julio C. Tello . Furthermore, a variety of skulls and bundles of mummies from the Paracas culture are exhibited in the Paracas History Museum in Peru and in the Museo Ceramico , which is located in the Bolivian Altiplano and contains artifacts found around the archaeological temple complex of Tiahuanaco and Pumapunku . Furthermore, there is a so-called skull space in the Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú , in which there are around 10,000 deformed skulls. A copy of a Paracas mummy bundle is exhibited in the Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum in Hildesheim , where it was examined with a CT scan . Many skulls of the Paracas culture have the peculiarity that they do not have an arrow suture ( Sutura sagittalis ) (see skull without arrow suture.jpg ). In science there are as yet no explanations for their lack. The Paracas skulls have a narrower forehead, longer and narrower face, larger eye sockets , longer nose, and larger palatine bone than other skulls found in Latin America. Even Julian Steward found out that at the Paracas mummies the skull shape from that of other known indigenous peoples in the ways different in that it has smaller features. Johann Jakob von Tschudi, was the first to discover osteological anomalies in ancient Peruvian skulls. The face dimensions (nasal and upper face index) of the Paracas skull deviate strongly from the mean values obtained for the north coast. The nose looks even narrower and longer and the upper face even higher than in the middle coast groups. An artificial skull deformation can be identified, which is typical of the Paracas. This deformation is also called Paracas-type skull deformation . There were heterogeneous deformations in the Paracas culture. For example, deformities of the brachycephaly , dolichocephaly and turricephalus types have been found.

Nazca culture

The Nazca culture, which is the successor to the Paracas culture and, together with the Paracas culture, is considered to be the originator of the Nazca lines , was the first to be scientifically described by the archaeologist Max Uhle . He studied it for the first time in 1901 and published in the following years, among other things, his important works Las ruinas de Moche (1913), Cronología sobre las antiguas culturas de Ica (1914) and The Nazca Pottery of Ancient Perú (1914). The Nazca culture was heavily influenced by the previous Paracas culture. This was shown by the fact that numerous customs and rites were adopted. So is the practice of skull deformation. The Paracas culture (800–200 BC) passed over into the Nazca culture and did not, as previously assumed, penetrate the Nazca territory from outside. Elongated skulls, as a result of skull manipulation, were also discovered during the excavations around the pyramids at Cahuáchi . The trophy heads discovered in the excavation site show a frontal-occipital deformation. An elongated head shape (long skull) was regarded by the Nazca as an ideal of beauty. The Nazca deformation is a typical anteroposterior deformation. Most often the frontal and occipital bones were flattened with the Nazca by tying small boards in front of the forehead of the infants in order to deform the skull during growth. The elongated head shapes created in this way are also often found in Nazca ceramics . The Cahuáchi Cemetery , which was discovered in the 1920s, contains many important burial sites over a period of 600 to 700 years. It also contained many mummies and skulls that had frontal trepanations. Many of those operated on survived the operation for a relatively long time. The dead were wrapped in splendid cloths and buried in a sitting, or often in a fetal position, in the dry desert soil. The extreme drought mummified the dead; the hot air dried out the corpse so that embalming was not necessary, which is why some of them are still very well preserved today. However, looters destroyed many of these graves.

Skull deformation in Central America

Mayans

The artificial skull deformation was a prominent feature of the Mayans' culture and was widespread. For the Mayans, the importance of deformation lay not only in aesthetics , but it also had religious and social significance. An elongated skull was considered noble by the Mayas and was not only reserved for representatives of a higher social class. In contrast to the deformation of the skull in Peru, which was only reserved for a higher class and also served to underline ethnic affiliation, the Mayas granted the privilege to deserving families, so that the offspring were able to pursue a wide range of social positions. Not only the Mayans, but also the Olmecs , an indigenous people who were native to the Gulf coast of Mexico, and the Aztecs practiced skull deformation in Central America.

The practice of intentional cranial deformation or flattening is well documented among the pre-Columbian Maya peoples and is evidenced by finds from the pre-classical era. Through the use of skull boards and other compression techniques applied to the growing child's skull, a wide variety of head shapes have been achieved, with different regions and time periods exhibiting different styles and ideals. The practice was used by both men and women and was not a specific characteristic of class or social status. A study that looked at over 1,500 skulls from the Maya region found that at least 88% had some form of intentional skull deformation. Some scholars believe that the Mayan practice of skull trepanation, like the practice of skull deformation, had cultural and identity-forming causes.

Skull deformation in pre-Hispanic mummies

Many pre-Hispanic mummies and human remains found on the South American continent show severe deformation of the skull. One of the most famous pre-Hispanic mummies showing a deformed skull is the Detmold children's mummy . The Detmold children's mummy has an abnormal skull shape that shows signs of turricephaly (a condition in which the early ossification of the skull causes an abnormal skull shape and is one of the most severe craniosynostoses ) . Some child mummies showing signs of skull deformity are believed to have died from the cranial changes caused by the compression bandages. However, research shows that this does not always have to be the cause of death. Examination of the skull of a 4-6 month old child mummy showing signs of skull deformation revealed that this individual died from an unusual morphology of the skull. The indigenous Aymara people , who are native to the Andean region between Peru and Bolivia, also practiced skull deformation. The Aymara wrapped their dead in cloths like the Nazca, which means that today Aymara mummy bundles can be viewed. In Aymara mummies, the most common circular skull deformation, also called Aymara deformation , is found. In the Aymara deformation, compression bandages were placed around the posterior half of the skull to produce the desired deformations.

Pre-Hispanic mummy, with a body 50 cm in length, a skull of almost the same size, extraordinarily large eye sockets and other anomalies, found in a mummy bundle near Cusco .

The Detmold children's mummy in the Lippisches Landesmuseum in Detmold : the abnormal shape of the skull is striking

Differences from other cultures

There are no significant differences between artificially deformed skulls found in Europe and Peru. The anthropologist Johannes Ranke , who was one of the first to study skull deformation in indigenous peoples of South America, stated:

"... The artificial deformation of the ancient Peruvian skull [...] can be explained like the generally weaker, but in principle completely identical artificial deformations of European skulls"

Other anthropologists also saw only a difference in the degree of deformity.

Historical speculation about a genetic origin

In the first half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century a debate arose over whether there was a population with hereditary d. H. natural dolichocephaly , or whether any deformation was purely intentional. RJ Graves believed in 1834 that some skulls belonged to an extinct human race "which is different from any form that exists today." Some anthropologists were of the opinion that this "long-skull breed" could be localized on the shores of Lake Titicaca . The ship's doctor, PF Bellamy , published a report in 1842 of two elongated skulls of toddlers discovered by his captain in 1838 and given to the Museum of the Devon and the Cornwall Natural History Society , which he diagnosed as lacking artificial pressure marks. He, too, believed that they came from another human race that had died out due to a mixture of blood with those who subsequently "became rulers of the country [meaning the Nazca ]." Mariano Eduardo de Rivero and Johann Jakob von Tschudi described 1852 a mummy who was pregnant at the time of death and in whose womb there was a fetus that had the same elongated skull formation as that of the artificially deformed Huanca skulls of adults Tschudi and Rivero write:

"... the same formation [d. H. the absence of artificial pressure marks] on the skull is evident even in children who have not yet been born; and based on this truth, we have had convincing evidence in the face of a fetus, locked in the womb of a mummy of a pregnant woman, which we found in a cave [here: a shaft grave] in Huichay , two leagues from Tarma , and which is at this moment is in our collection. Professor D'Outrepont , well known in the obstetrics department, has assured us that the fetus is seven months old. It can be assigned to a very clearly defined formation of the cranium , to the tribe of the Huancas . We present the reader with a drawing of this definitive and interesting evidence in contrast to the proponents of mechanical influence who see it as the sole and exclusive cause of the phrenological nature of the Peruvian race. "

Rivero and Tschudi initially assumed that all the skulls found were deformed solely by artificial influence, but they revised their hypothesis in view of the examination of skulls of small children, which "[...] had more abnormalities than the adult skulls." In addition to the other mummies in the Lima Collection in the National Museum of Lima, she made similar discoveries which she believes are evidence of the thesis of natural origin. At the beginning of the 20th century, Johannes Ranke analyzed "[...] several skulls with more or less pronounced pathological changes". After Johannes Ranke had an in-depth conversation with Rudolf Virchow and Abraham Lissauer , he was surprised by the results of his investigation: "Until then, I had not doubted the intended skull deformation among the old Peruvians". Virchow himself assumed that there had been a development from accidental to deliberate, from simple to complicated deformation. However, critics of Rivero's and Tschudie's analyzes emerged early on. For example, Canstatt and Eisenmann described the analysis of two mummies Riveros and Tschudies as "insubstantial". Nor did Joseph Barnard Davis and John Thurnam see complete evidence that a population with natural dolichocephaly had existed. Crania Americana , published by Samuel George Morton in 1839, states:

"... Without the accuracy of Dr. To demean Tschudi, we can seek further evidence before we admit that these extraordinary shapes of the head like this are natural, and still agree on certain doubts whether these fantastic shapes are not always the result of art and manipulation. "

Samuel George Morton, who had initially been convinced that there was a population with natural dolichocephaly and had propagated this thesis, declared shortly before his death that he was deeply convinced that all the skulls examined in Crania Britannica were subject to the artificial influence.

gallery

So-called "Hollow Baby": figure of an Olmec with a deformed skull; exhibited in the National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico)

Lithograph by James Basire : (1842) skulls of young children classified as Titicacatians; published in the Journal of Natural History .

An approximately 550 year old Peruvian child mummy is being prepared for a CT scan at the Naval Medical Center San Diego .

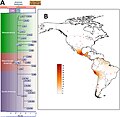

Phylogenetics and distribution of haplogroup C (mtDNA) 1b: Two extreme areas of distribution of the haplogroup are visible; one in Mexico and the other in Peru.

Cranial structure of a long skull, which can be assigned to the Paracas culture and was found in Pumapunku . To see: The absence of the sagittal suture .

Web links

- Mathematical analysis of artificial skull deformation

- Photo gallery: Trepanation: The Inca cranial surgery

- Photo gallery: Holes in the head

literature

- Peter C. Gerszten: An investigation into the practice of cranial deformation among the Pre-Columbian peoples of northern Chile. In: International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 3, 1993, pp. 87-98.

- MP Rhode, BT Arriaza: Influence of cranial deformation on facial morphology among prehistoric South Central Andean populations. In: American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 130, 2006, pp. 462-470.

- C. Torres-Rouff, LT Yablonsky: Cranial vault modification as a cultural artifact: a comparison of the Eurasian steppes and the Andes. In: Homo. 56, 2005, pp. 1-16.

- Rudolf Virchow: About skull shape and skull deformation. In: Correspondence sheet for Anthrop. 32, 10-12, 1892, pp. 135-139.

- Pedro Weiss: Tipología de las deformaciones cefálicas de los antiguos peruanos, según la osteología cultural. In: Revísta del Museo Nacional. 31, 1962, pp. 13-42.

- EH Froeschner: Two examples of ancient skull surgery. In: J Neurosurgery. 76, 1992, pp. 550-552.

- Vera Tiesler: The bioarchaeology of artificial cranial modifications: New approaches to head shaping and its meanings in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and beyond. Vol. 7, Springer Science & Business Media, 2013, ISBN 978-1-4614-8759-3 .

- Vera Tiesler: Head shaping and dental decoration among the ancient Maya: archeological and cultural aspects. In: Proceedings of the 64th Meeting of the Society of American Archeology. 1999.

- Stephanie Panzer et al .: Reconstructing the life of an unknown (approx. 500 years-old South American Inca) mummy-multidisciplinary study of a Peruvian Inca mummy suggests severe chagas disease and ritual homicide. In: PLOS ONE . 9 (2), 2014, p. E89528.

Remarks

- ↑ See Walker (1997), who found the "earliest clear evidence of trepanation" in a burial site near Ensisheim in the Alsace region of France (5100-4900 BC). See also the comment in Tiesler (2003a).

- ↑ a b c d e f Angelika Franz: Inka were world champions in skull surgery. In: Spiegel online. May 15, 2008.

- ^ Ancient cranial surgery: Practice of drilling holes in the cranium that dates back thousands of years. ( Memento from April 24, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) In: ScienceDaily. 2013, accessed March 30, 2017.

- ^ Stanley Finger: Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations Into Brain Function. 1994, p. 6.

- ↑ Verano (1997), cited in Tiesler (2003a). In this context, “Successful” means how the survival rate was classified by scientists in the examined individual and does not necessarily mean the effectiveness of trephination as a cure for a pre-existing disease. In general, it is difficult to determine from osteological data whether or not the treatment has been successful in a particular individual and whether or not the symptoms of the patient's medical condition have been alleviated.

- ↑ Mysterious rafters . In: Der Spiegel . No. 2/2014 ( spiegel.de [accessed on April 25, 2017]).

- ^ Tumi, the ceremonial knife. Discover Peru. Retrieved April 25, 2017 .

- ↑ a b John Bonifield: Were mystery holes in skulls an ancient aspirin? In: CNN.

- ↑ Science News: Incan skull surgery , accessed March 30, 2017.

- ↑ Raul Marino: Preconquest Peruvian Neurosurgeons ( Memento of the original from June 17, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Kushner, David S., John W. Verano, and Anne R. Titelbaum: Trepanation Procedures / Outcomes: Comparison of Prehistoric Peru with Other Ancient, Medieval, and American Civil War Cranial Surgery. , World neurosurgery, (2018).

- ^ Museo Regional De Ica: The skull operations and long skulls of the Paracas culture.

- ↑ a b c d Vera Tiesler: New Approaches to Head Shaping and its Meanings in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and Beyond.

- ↑ a b Vera Tiesler: Head shaping and dental decoration among the ancient Maya: archeological and cultural aspects. In: Proceedings of the 64th Meeting of the Society of American Archeology. 1999.

- ↑ Rodríguez (1972), cited in Tiesler (2003a).

- ↑ a b Rolf Seeler: Peru and Bolivia. Indian cultures, Inca ruins and the baroque colonial splendor of the Andean states. DuMont, Cologne 2001, ISBN 3-7701-4786-3 , p. 161, ( available from Google Books).

- ^ BBC: Why early humans reshaped their children's skulls

- ↑ a b E. Schijman: Artificial cranial deformation in newborns in the pre-Columbian Andes. In: Child's nervous system: ChNS: official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. Volume 21, Number 11, November 2005, pp. 945-950, doi: 10.1007 / s00381-004-1127-8 . PMID 15711831 .

- ↑ Michael Obladen: In God's Image? The Tradition of Infant Head Shaping. In: Journal of Child Neurology. 27, 2012, p. 672, doi: 10.1177 / 0883073811432749 .

- ↑ a b From a Peruvian child to a Baron from Budapest. (No longer available online.) In: KATU.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2013 ; accessed on November 21, 2014 (English).

- ^ Paleopathology: Neurosurgical diseases of the skull in the early Middle Ages. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. 98 (48), 2001, pp. A-3196 / B-2706 / C-2513.

- ↑ Stephanie Panzer, Oliver Peschel u. a .: Reconstructing the Life of an Unknown (approx. 500 Years-Old South American Inca) Mummy - Multidisciplinary Study of a Peruvian Inca Mummy Suggests Severe Chagas Disease and Ritual Homicide. In: PLoS ONE. 9, 2014, p. E89528, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0089528 .

- ↑ M. Friess, M. Baylac: Exploring artificial cranial deformation using elliptic Fourier analysis of Procrustes aligned outlines. In: American journal of physical anthropology. Volume 122, Number 1, September 2003, pp. 11-22, doi: 10.1002 / ajpa.10286 . PMID 12923900 .

- ↑ Mercedes Okumura: Differences in types of artificial cranial deformation are related to differences in frequencies of cranial and oral health markers in pre-Columbian skulls from Peru

- ^ Tyler G. O'Brien, Lauren R. Peters, Marc E. Hines: Artificial Cranial Deformation: Potential Implications for Affected Brain Function.

- ^ FJ Carod Artal, CB Vázquez Cabrera: Neurological paleopathology in the pre-Columbian cultures of the coast and the Andean plateau (I). Artificial cranial deformation. In: Revista de neurologia. Volume 38, Number 8, 16.-30. Apr 2004, pp. 791-797. PMID 15122550 .

- ↑ Thurid Katrin Klunker: The craniological research of Hermann Welcker (1822–1897) with special consideration of the skull collection of the Anatomical Institute in Halle / Saale - examinations of frontal sutures, supranasal sutures and accessory bones.

- ↑ Quoted from: B. Oetteking: The Jesup North Pacific Expedition XI, Craniology of the North Pacific Coast. GE Stechert, New York 1930.

- ^ JH Torgersen: Hereditary factors in the sutural pattern of the skull. In: Acta Radiologica. 36, 1951, pp. 374-382.

- ^ NS Ossenberg: The influence of artificial cranial deformation on discontinuous morphological traits. In: American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 33, 1970, pp. 375-372.

- ^ MM Lahr: The Evolution of Modern Human Diversity. A Study of Cranial Variation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1996.

- ^ MY El-Najjar, GL Dawson: The effect of artificial cranial deformation on the incidence of wormian bones in the lambdoidal suture. In: Am J Phys Anthropol. 46, 1977, pp. 155-160. Medline

- ^ John M. Graham: Recognizable Patterns of Human Deformation. Saunders, Philadelphia et al. 1988, ISBN 0-7216-2338-7 , p. 316.

- ↑ Mercedes Okomura: Differences in types of artificial cranial deformation are related to differences in frequencies of cranial and oral health markers in pre-Columbian skulls from Peru. In: Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas. vol. 9, no. 1, Jan./Apr. 2014.

- ↑ a b c R. J. Graves: Remarkable Skulls found in Peru. In: The Dublin Journal of Medical and Chemical Science. Volume 5, No. 3, 1834, p. 477.

- ↑ James Cowles: Researches into the physical history of mankind. 5 vol. pl. map. 1836, p. 319.

- ↑ Johannes Ranke: About old Peruvian skulls.

- ↑ a b Kari Kunter: Contributions to the population history in western South America with special consideration of the skeletal finds from Cochasquí, Ecuador. Diss. Giessen (1969), p. 95

- ↑ Micahhanks: Remains Uncovered at Arkaim, Russia, Display Cranial Deformation .

- ↑ British and Foreign Medico-surgical Review. 1860, p. 165.

- ↑ Martin Frieß, Michel Baylac: Exploring Artificial Cranial Deformation Using Elliptic Fourier Analysis of Procrustes Aligned Outlines .

- ^ Stanley Finger: Origins of Neuroscience.

- ^ Museo regional de Ica: The regional museum of Ica.

- ↑ Peter Kaulicke: Paracas y Chavin. Variacones sobre un tema longevo. In: Boletín de Arqueología PUCP. 17, 2013, p. 265. ( online, accessed January 5, 2017 ).

- ↑ Cultura Paracas on historiaperuana.pe, accessed on January 5, 2017.

- ↑ Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos: La cultura Paracas y sus vinculaciones con otras del Centro Andino.

- ↑ Elsa Tomasto-Cagigao, Markus Reindel and Johny Isla: Paracas Funerary Practices in Palpa, South Coast of Perú. In: Peter Eeckhout, Lawrence S. Owens (Eds.): Funerary Practices and Models in the Ancient Andes. The Return of the Living Dead . Cambridge University Press, New York 2015, p. 69.

- ^ Federico Kauffmann Doig: Historia y arte del Perú antiguo. Volume is missing, 2002, p. 236.

- ↑ Cultura Paracas on historiaperuana.pe, accessed on February 18, 2017.

- ↑ Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum Hildesheim Press information on the special exhibition "Mummies of the World"

- ↑ Monique Marie-Claude Fouant: The Skeletal Biology and Pathology of Pre-Columbian Indians from Northern Chile (1984) , p. 9.

- ^ Thor Heyerdahl: Early man and the ocean. 1979, p. 101.

- ↑ J. Aucamp et al .: A historical and evolutionary perspective on the biological significance of circulating DNA and extracellular vesicles. 2016.

- ↑ RH Tykot, A. Metroka, M. Dietz, RA Bergenfield: Proceedings of the 37th International Symposium on Archaeometry. Springer, 2011, ISBN 978-3-642-14678-7 , p. 443.

- ^ German Archaeological Institute: Paracas

- ^ Helaine Silverman: Handbook of South American Archeology.

- ↑ Indian World: Nazca , accessed March 30, 2017.

- ↑ Pam Barrett: Peru , p. 178.

- ↑ Romtd: Archeology: Discover the secrets of the pre-Columbian mummies ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Scientific news from around the world: Archaeologists dig 1,000 year old Maya cemetery

- ↑ National Geographic: "Haunted" Maya Underwater Cave Holds Human Bones

- ^ RA Joyce: Performing the body in pre-Hispanic Central America. Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics. 1998, pp. 147-165.

- ↑ National Geographic: Royal Massacre Site Discovered In Ruins Of Ancient Maya City

- ^ Museum of Technology: Artificial skull deformation: Großkopferte p. 26.

- ↑ MF Sheila, Mendonça de Souza, Karl J. Reinhard, Andrea Lessa: Cranial Deformation as the cause of death for a child from the chillon river valley, Peru

- ↑ Donald J. Ortner: Identification of Pathological Conditions in Human Skeletal Remains. Academic Press, 2003, ISBN 0-08-052563-6 , p. 165.

- ^ WJ Schull, F. Rothhammer: The Aymara: Strategies in Human Adaptation to a Rigorous Environment. Springer, 2012, ISBN 978-94-009-2141-2 .

- ↑ El Comercio: extraña momia fue analizada por especialistas

- ^ Andina: Momias de Andahuaylillas son infantes de época prehispánica.

- ↑ Johannes Ranke: About old Peruvian skulls.

- ↑ Herbert Zemen: The lithographer Leopold Müller ( Memento of the original from April 23, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ A b c Mariano Eduardo Rivero, Juan Diego de Tschudi: Antigüedades Peruanas. Text tape. Imprenta Imperial de la Corte y de Estado, Viena 1851, (digitized)

- ↑ J. Aucamp et al .: A historical and evolutionary perspective on the biological significance of circulating DNA and extracellular vesicles (2016)

- ↑ George Combe: Crania americana; or, A comparative view of the skulls of various aboriginal nations of North and South America p. 25.

- ↑ Janine Aucamp, Abel J. Bronkhorst a. a .: A historical and evolutionary perspective on the biological significance of circulating DNA and extracellular vesicles. In: Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 73, 2016, p. 4355, doi: 10.1007 / s00018-016-2370-3 .

- ^ Huxley: Journal of the Ethnological Society of London, Volume 2, p. 301.

- ^ A b P. F. Bellamy: A brief Account of two Peruvian Mummies in the Museum of the Devon and Cornwall Natural History Society. In: The Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Volume 10, No. 63, 1842, pp. 95-100.

- ^ PF Bellamy: A brief Account of two Peruvian Mummies in the Museum of the Devon and Cornwall Natural History Society. In: The Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Volume 10, No. 63, 1842, pp. 95-100.

- ↑ Tschudi quoted in Die Culturländer des alten America (1902) p. 147 by Adolf Bastian

- ^ Tschudi cited in Proceedings of the Royal Physical Society of Edinburgh (1858–1955). P. 76 by James M'Bain

- ↑ Tschudi cited in Crania Britannica: Delineations and Descriptions of the Skulls of the Aboriginal and Early Inhabitants of the British Islands: with Notices of Their Other Remains. Decade 3. p. 35 by Joseph Barnard Davis, John Thurnam

- ↑ Tschudi quoted in The Canadian Journal of Industry, Science and Art, Volume 6, p. 420.

- ↑ Tschudi by George Palmer in The Migration from Shinar: Or, the Earliest Links Between the Old and New Continents 1879

- ↑ Tschudi quoted in The National Quarterly Review, Volumes 7–8

- ↑ Outrepont, Joseph Servatius d '(1775–1845) full professor for obstetrics at the University of Würzburg and director of the school for midwives there: Outrepont, Joseph Servatius d'

- ^ PF Bellamy (1842): A brief Account of two Peruvian Mummies in the Museum of the Devon and Cornwall Natural History Society. In: Annals and Magazine of Natural History, X October.

- ↑ Tschudi quoted in The Canadian Journal of Industry, Science and Art. Volume 6, p. 420.

- ↑ Tschudi by George Palmer in The Migration from Shinar: Or, the Earliest Links Between the Old and New Continents 1879

- ↑ Johannes Ranke: About old Peruvian skulls.

- ↑ Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde , Volume 26, Walter de Gruyter, 2004, p. 574.

- ↑ Eisenmann Canstatt: Annual report on the progress of the entire medicine in all countries (1843)

- ^ Joseph Barnard Davis, John Thurnam: Proceedings of the Royal Physical Society of Edinburgh (1858-1955). P. 76 by James M'Bain

- ^ Joseph Barnard Davis, John Thurnam: Crania Americana; or, A Comparative View of the Skulls of Various Aboriginal Nations of North and South America: To which is Prefixed An Essay on the Varieties of the Human Species. J. Dobson, Philadelphia 1839.

- ↑ Alberto Gómez-Carballa, Laura Catelli, Jacobo Pardo-Seco, Federico Martinón-Torres, Lutz Roewer, Carlos Vullo & Antonio Salas: The complete mitogenome of a 500-year-old Inca child mummy