Pumapunku

Pumapunku , Pumapunku or Pyramid of Pumapunku ( Aymara and Quechua : for "Gate of the Puma") is the largest pyramidal from monolithic existing buildings temple complex of ruins Tiahuanaco and is characterized by its exact architecture. Although Pumapunku is largely in ruins, huge floor slabs up to 7 m long and 4 m wide with precisely right-angled teeth and extremely precise cuts are still preserved. The Tiahuanaco ruins are located near the place of the same name in Bolivia . The area of Pumapunku extends over approx. Seven hectares. Pumapunku is almost 4000 meters above sea level in the high plateau of the Altiplano near Lake Titicaca . All of Pumapunku was held together with an ingenious system of clamps. Diorite blocks were found that were systematically prefabricated and assembled to form walls using the modular principle using clips.

The Pumapunku ritual complex, which is associated with a wide forecourt in the east, was built a few hundred meters southwest of Akapana at about the same time as the Akapana pyramid. Three platforms were built on an area of approx. 167 × 116 meters. Pumapunku was a construction that was not finished and which changed over time due to constant construction work. The fact that large parts of Pumapunku have sunk into the ground and the huge monoliths are scattered across the landscape suggests that a natural disaster prevented the completion of the structures.

history

The site was first mentioned in history by the Spanish conquistador Pedro de Cieza de León . He discovered the ruins of Tiwanaku and Pumapunku by accident in 1549 while searching for the Inca capital.

Pumapunku is dated to the 6th century AD. It was a significant site for the Incas because they believed that this was the place where the world was created. The entire complex consists of an open space, the central esplanade, the terraced, platform-like, stone-clad embankment and another walled square.

investment

The actual "Pumapunku" is a terraced mound that was attached with stones. This is 167.36 meters long in its north-south axis and 116.7 meters in the south-west axis. In the northeast and southeast corners there are cantilevers around 20 meters wide, which extend 27.6 meters to the north and south, respectively. The so-called "Plataforma Litica" is located on the eastern edge of Pumapunku. This platform consists of a stone terrace measuring 6.75 × 38.72 meters. It was secured with many, extremely large stone blocks. All other stones used in Pumapunku are made from a mixture of andesite and red sandstone . Pumapunku mainly consists of clay. The parts below consist of river sand and field stone without clay. Due to various excavations, it is believed that there were three main eras in which construction was intense, in addition to individual minor repair and redesign work.

At its peak, it is assumed, Pumapunku must have been “almost unimaginably beautiful, richly decorated with metal plates, colorful ceramics and ornaments, attended by elegantly dressed citizens, priests in splendid robes and elites, adorned with exotic jewels.” Due to a lack of written records However, it is difficult to make reliable statements about the age, origin and use of this system. In addition, there have been various changes due to looting, stone demolition for construction purposes and weather influences.

The entire area within a radius of about one kilometer between the Pumapunku and the Kalasasaya complex was investigated using radar , magnetometry , geoelectrics and geomagnetics . The geophysical data collected during this survey and excavation revealed a variety of other man-made structures between the two complexes. These structures include foundation walls, water channels, pool-like facilities, terraces, residential areas and extensive gravel paths, all of which are now buried under layers of soil.

reconstruction

In 2018, archaeologist Alexei Vranich created a computerized virtual model of Pumapunku. He also used 3D printing techniques to reproduce the megaliths true to scale.

Age

Researchers have tried to determine the age of pumapunku since the Tihuanaco site was discovered. As Andean specialist William H. Isbell , professor at the University of Binghamton , describes, von Vranich determined a radiocarbon date by measuring organic material from the lowest and oldest layer of the artificial hill on which Pumapunku stands . These layers were piled up during the first of a total of three construction epochs. The initial construction of Pumapunku is dated to 536–600 AD (1510 ± 25 oc c14, calibrated date). Because the radiocarbon date was determined by the underlying foundation of andesite and sandstone, the structure above must have been built sometime after 536–600 AD. The excavations of Vranich determined that clay, sand and gravel lie directly on closed Pleistocene sediments . Furthermore, these excavations also revealed the complete absence of any other pre-Inca cultural evidence within the Tihuanaco / Pumupunku area.

Technology and construction

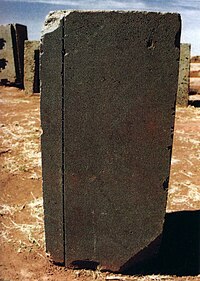

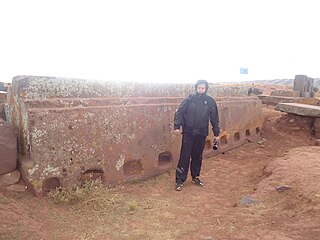

Pumapunku consists of huge stone slabs that are scattered all over the landscape. Some stone slabs have clean cut edges.

The largest monolith found is 7.81 meters long, 5.17 meters wide, an average of 1.07 meters deep and weighs about 131 tons. On the stone blocks weighing up to 130 t, the grooves in which brackets made of bronze or copper hardened with arsenic were inserted to clamp the plates, which weigh tons, are striking. The second largest monolith found in Pumapunku is 7.9 meters long, 2.5 meters wide and approximately 1.86 meters deep. Its weight is estimated at 85 tons. Both stones are part of the "Plataforma Litica", a platform made of red sandstone . On the basis of precise petrographic and chemical analyzes and a comparison with known quarries, archaeologists have concluded that these and other blocks from a quarry about ten kilometers away near Lake Titicaca were transported over a considerable incline to Tihuanaco. Smaller andesite stones that were used as facing bricks and for stone carving came from a quarry 90 kilometers away, within the Copacabana Peninsula .

In addition to the mostly used sandstone, andesite (sometimes described as diorite ) was also used as a rock material. Exactly opposite recesses were discovered on these blocks, which allowed the blocks to be linked exactly. This application of the modular technology suggests that the stone blocks, which weighed tons, were systematically prefabricated.

When the walls of Pumapunku were built, every stone was hewn so precisely that it fits the neighboring stone exactly and without gaps. The blocks fit together like a puzzle and form weight-bearing supports without the use of mortar . A common machining technique is to cut the top of a lower stone at a certain angle and then put another stone on top and cut it off at the same angle. The precision with which the angles were used to achieve flowing connections is an indication of a highly developed knowledge of stone processing and geometry . Many of these connections are so precise that not even a razor blade will fit between the stones. Many walls made of accurately cut, rectangular blocks are of such uniformity that they could be exchanged at will and still the surface level and even the joint would be preserved. Although the blocks all have different dimensions, they are still close together.

The blocks are so precisely cut that one suspects a kind of mass production , which was not introduced by the Tihuanaco Incas until centuries later. A few unfinished blocks were found and this enabled design techniques to be understood. Apparently the rough block was first worked with a stone hammer , as is still done today in the local andesite quarries. After that, they were slowly ground and polished with flat stones and sand. Archaeologists suspect that a large group of workers handled the transport of the blocks . To this end, a number of hypotheses have been drawn up as to how these workers transported the stones. Nevertheless, these hypotheses remain speculative. Two of the most serious hypotheses suggest the use of ropes and ramps .

Another notable detail is the I-shaped clamps made from a unique copper-arsenic-nickel-bronze alloy . These brackets were also used on a canal found at the bottom of the neighboring Akapana pyramid . They were used to connect the blocks that spanned the walls and floor of the stone-lined canals and drained the lower courtyards. I-clamps of unknown alloy were also used to hold together the massive plates that made up the four large platforms of Pumapunku. In addition, I-shaped brackets were cast exactly into shape in the southern canal. In contrast, the staples used on the Akapana Canal were created by cold hammering copper-arsenic-nickel-bronze blocks. The unique copper-arsenic-nickel-bronze alloy is also found in other metal artifacts found in the region between Tiahuanaco and San Pedro de Atacama and produced during the late Middle Classical period around AD 600–900.

The temple complexes, built without mortar and cement, were, like many other pre-Inca buildings, completely earthquake-resistant , which is why a cause other than a strong earthquake is believed to have destroyed Pumapunku. The technique of joining stone blocks using bronze clamps was copied by the Inca and used in Ollantaytambo .

The engineers at Tiahuanaco must also have had knowledge of civil infrastructure , as they created a functioning irrigation system with hydraulic mechanisms and sewers for this complex .

architecture

Pumapunku is a large, platform-like mound of earth, the three levels of which are secured by stone retaining walls. The entire area resembles a square. To secure the weight of these massive structures, the Tiahuanaco architects were extra careful with the foundations. Often they added stones that matched the stone substrate directly. Or they dug precise trenches , which they filled with carefully layered sedimentary stones to support large stone blocks, a technique that is still used today. By alternating layers of sand on the inside and layers of composite materials on the outside, the fillings were designed so that they overlap at the joints. Essentially, the contact points are graded in order to create a stable basis. In front of Pumapunku, huge monolithic stone walls with fish ornaments can be found, which is why the port of Tiwanaku was assumed here. However, the stone walls are over 20 kilometers away from Lake Titicaca, so that the water level of the lake should have been significantly higher at that time.

A section of the wall by Pumapunku decorated with diamond-shaped stair motifs. This motif is symbolic of the sun cult and is also found in the weaving art of the Wari culture .

The sun gate

Due to the nature of the famous sun gate of the Tiwanaku ruins , it is believed that it is out of place today and was originally part of Pumapunku. Not only the nature of the gate, but also the lack of a threshold suggest that it was probably formerly part of the Pumapunku complex. The Creator God of the Inca Wiraqucha is depicted on the sun gate . In a legend, Wiraqucha caused almost everyone around Lake Titicaca to die in a deluge called Unu Pachakuti (the turn of the water). According to legend, he let two survive to bring civilization into the world.

Cultural and religious significance

According to current research, it is believed that the Pumapunku complex as well as the surrounding temples, the Akapana pyramid, Kalasasaya , Putuni and Kerikala were used as spiritual and ritual centers for the Tiahuanaco region. This area could have been viewed as the center of the Andean world and attracted pilgrims from far away. Pumapunku may have been intentionally integrated into the mountainous region of the Illimani , as the Tiahuanaco believed that the spirits of their dead were at home on this sacred peak. Perhaps the spiritual meaning has also been enhanced through the use of hallucinogenic plants to create a “life changing experience”. The importance of these substances for the Tiahuanaco is also shown by studies of hair samples taken from mummies that were found in the Tiahuanaco culture in northern Chile, including babies. Remnants of psychoactive substances were found.

As was characteristic of civilizations around this time, human sacrifice was part of the Tiahuanaco culture. The remains of dismembered bodies have been found across the area. Ceramic artifacts depict images of warriors wearing puma skulls, beheading their enemies, holding trophy skulls, and wearing belts with their enemies' heads hanging on them. A large number of deformed and trephined skulls were also found in Pumapunku , which can be examined in the local museum. Because of certain markings on stones found at Pumapunku, it is believed that the Sun Gate was originally part of Pumapunku.

rise and fall

The Tiahuanaco culture and use of temples seems to have peaked between 700 and 1000 AD. At this point in time the temple area and the surrounding area could have been populated by up to 400,000 people. An extensive infrastructure was built, including a complex irrigation system that stretched over 80 km². This made it possible to plant potatoes , quinoa , corn and other crops . At the height of the Tiahuanaco culture, the entire area around Lake Titicaca, including what is now Bolivia and Chile , was probably dominated or at least influenced.

Apparently around AD 1000 this civilization ended abruptly. Researchers are still looking for answers as to why this happened. A likely scenario involves rapid climate change with extreme drought. Since the inhabitants were unable to produce sufficient quantities of food, it is believed that the Tiahuanaco spread over the mountain meadows and then disappeared completely. It is also believed that this happened before Pumapunku was completed.

Trivia

According to pre-astronautics representative Erich von Däniken , who is known for his controversial theses, Pumapunku represents a trace of extraterrestrial life on earth.

gallery

Web links

- Picture gallery - Free University of Berlin

- Interactive Archaeological Investigation at Pumapunku Temple - Archaeological Institute of America

Individual evidence

- ↑ Julia Müller: Cultura como campo para el desarrollo - culture in sustainable development work using the example of the pre-Columbian sites Tiwanaku and Cuzco , p. 84

- ^ UNESCO: Tiwanaku: Spiritual and Political Center of the Tiwanaku Culture

- ↑ Julia Müller: Cultura como campo para el desarrollo - culture in sustainable development work using the example of the pre-Columbian sites Tiwanaku and Cuzco , p. 86

- ^ Alan L. Kolata : The Tiwanaku: Portrait of an Andean Civilization . Wiley-Blackwell , December 11, 1993, ISBN 978-1-55786-183-2, (Retrieved August 9, 2009).

- ^ H. James Birx: Encyclopedia of Anthropology . SAGE Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, 2006.

- ↑ a b c d Isbell, William H. (2004), "Palaces and Politics in the Andean Middle Horizon," in Evans, Susan Toby; Pillsbury, Joanne, Palaces of the Ancient New World (PDF), Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, pp. 191-246, ISBN 0-88402-300-1 , accessed April 26, 2010

- ↑ a b c d e f Vranich, A., 1999, Interpreting the Meaning of Ritual Spaces: The Temple Complex of Pumapunku, Tiwanaku, Bolivia. Doctoral dissertation, The University of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ a b c d Vranich, A., 2006, "The Construction and Reconstruction of Ritual Space at Tiwanaku, Bolivia: AD 500-1000." Journal of Field Archeology 31 (2): 121-136.

- ↑ a b c d e Ponce Sanginés, C. and GM Terrazas, 1970, Acerca De La Procedencia Del Material Lítico De Los Monumentos De Tiwanaku. Publication no. 21. Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Bolivia .

- ↑ a b Protzen, J.-P., and SE. Nair, 2000, On Reconstructing Tiwanaku Architecture: The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 358-371.

- ↑ Ernenweini, EG, and ML Konns, 2007, Subsurface Imaging in Tiwanaku's Monumental Core. Technology and Archeology Workshop. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC

- ^ Williams, PR, NC Couture and D. Blom, 2007 Urban Structure at Tiwanaku: Geophysical Investigations in the Andean Altiplano. In J. Wiseman and F. El-Baz, eds., Pp. 423-441. Remote Sensing in Archeology. Springer, New York.

- ↑ Alexei Vranich: Reconstructing ancient architecture at Tiwanaku, Bolivia: the potential and promise of 3D printing

- ↑ Julia Müller: Cultura como campo para el desarrollo - culture in sustainable development work using the example of the pre-Columbian sites Tiwanaku and Cuzco , p. 84

- ↑ Julia Müller: Cultura como campo para el desarrollo - culture in sustainable development work using the example of the pre-Columbian sites Tiwanaku and Cuzco , p. 84

- ↑ Nicholas Tripcevich, Kevin J. Vaughn: Mining and Quarrying in the Ancient Andes: Sociopolitical, Economic, and Symbolic Dimensions . Springer Science & Business Media, 2012, ISBN 978-1-4614-5200-3 , p. 71 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed May 20, 2018]).

- ↑ a b Julia Müller: Cultura como campo para el desarrollo - culture in sustainable development work using the example of the pre-Columbian sites Tiwanaku and Cuzco , p. 86

- ↑ Robinson, Eugene (1990). 'In Bolivia, Great Excavations; Tiwanaku Digs 'Unearthing New History of the New World', The Washington Post. Dec 11, 1990: d.01.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Protzen, Jean-Pierre; Stella Nair, 1997, Who Taught the Inca Stonemasons Their Skills? A Comparison of Tiahuanaco and Inca Cut-Stone Masonry: The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians . vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 146-167

- ↑ Lechtman, HN , 1998, Architectural cramps at Tiwanaku: copper-arsenic-nickel bronze In Metallurgica Andina : In Honor of Hans-Gert Bachmann and Robert Maddin, edited by T. Rehren, A. Hauptmann, and JD Muhly, pp. 77-92. German Mining Museum , Bochum, Germany.

- ↑ Lechtman, HN, 1997, El bronce arsenical y el Horizonte Medio. En Arqueología, anthropología e historia en los Andes. in Homenaje a María Rostworowski , edited by R. Varón and J. Flores, pp. 153-186. Instituto de Estudios Peruanos , Lima.

- ↑ Julia Müller: Cultura como campo para el desarrollo - culture in sustainable development work using the example of the pre-Columbian sites Tiwanaku and Cuzco , p. 129

- ↑ a b c d Young-Sánchez, Margaret, 2004, Tiwanaku: Ancestors of the Inca - http://westminster.worldcat.org/title/tiwanaku-ancestors-of-the-inca/oclc/55679655&referer=brief_results

- ↑ Julia Müller: Cultura como campo para el desarrollo - culture in sustainable development work using the example of the pre-Columbian sites Tiwanaku and Cuzco , p. 86

- ^ W. Alva, M. Longhena: Inkas - The great people of the Andes. (2002).

- ↑ Margaret Young-Sanchez . Tiwanaku: Ancestors of the Inca . Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO 2004.

- ^ Meyers: Tiwanaku-Wari , p. 345

- ^ Morell, Virginia (2002). Empires Across the Andes National Geographic. Vol. 201, Iss. 6: 106

- ↑ Choi, Charles Q. "Drugs Found in Hair of Ancient Andean Mummies" , National Geographic News, Oct. 22, 2008. Accessed Nov. 4, 2011.

- ↑ a b Kolata, AL (1993) The Tiwanaku: Portrait of an Andean Civilization. Wiley-Blackwell, New York, New York. 256 pp. ISBN 978-1-55786-183-2

- ↑ a b Janusek, JW (2008). Ancient Tiwanaku, Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, United Kingdom. 362 pp. ISBN 978-0-521-01662-9

- ↑ Anja Richter: The extraterrestrials will come back in 20 years In: Die Welt , May 22, 2014