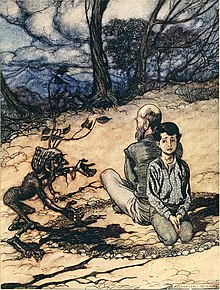

The king of the golden mountain

The king of the golden mountain is a fairy tale ( ATU 400, 518, 974 ). It is in the children's and house tales of the Brothers Grimm at position 92 (KHM 92).

content

A merchant accidentally prescribes his son to a black male. After the twelve-year period has expired, however, they disagree and the son has to go down the river in a boat. The father thinks he is dead. The son finds an enchanted castle. At the request of the king's daughter, who has been transformed into a serpent, he redeems the kingdom. In addition, he lets black men beat him to death for three nights without saying a word, and she brings him back to life. He marries her and becomes king. After eight years he wants to see his family again. She does not want that and makes him promise not to wish her to his parents with the wishing ring she gives him. He breaks the promise in anger when his parents don't believe his story. She is so angry about this that she leaves him alone at the river without the ring to take another man. On his way back to the castle, he meets three giants, from whom he removes a magical cloak, sword and shoes. In doing so, he takes back his wife and dominion.

Grimm's note

Grimm's comment notes on the origin: “According to the story of a soldier.” In a variant “from Zwehrn” (by Dorothea Viehmann ) a fisherman prescribes his son to the devil for rich fishing to pay off his debts. The son makes a circle around himself in the meadow and holds onto the Bible until the devil has to leave. He redeems a princess in a haunted house by, on the advice of a headless servant, tolerating the torment of ghosts without fear (cf. KHM 4 ). They ball it into a ball and play bowling with it, but a ghost heals it with oil. The third night it is to be boiled, falls by the cauldron, and the princess is redeemed. But when he is gone, she becomes engaged to a king's son. On the way he loots seven- league boots and camouflage coat. With that he stands behind her and holds her hand when she wants to eat. "If you find the old key again, you don't need the new one" (cf. KHM 67 ).

Grimms still mention many references: Erfurt Collection ( Wilhelm Christoph Günther , 1787) the gold egg . Regarding the miraculous gifts, they refer to their note on KHM 133 The Dancing Shoes ; Swedish with Cavallius "S. 182 "; Pröhle “Kinderm. No. 22 “; 1001 nights "10, 302"; Indian in Somadeva "1, 19. 20 (see Berlin. Jahrb. für deutsche Sprache 2, 265)"; Arabic "in the continuation of the 1001 nights 563–624 (see Val. Schmidts Fortunat pp. 174–178)”; Norwegian at Asbjörnsen "S. 53. 171 ”, Hungarian by Mailath and Gaal No. 7. They highlight a Tatar tale from Relations of Ssidi Kur : The son of the chan travels with his servant, he steals a cap that hides you from people, God and evil spirits and seven mile boots. You compare the Nibelungen saga in detail (see also KHM 91 , 166 ). For the Jephtha motif of the prescribed child, they call KHM 55 Rumpelstiltskin , for the three nights of torment to overcome the ghosts “old Danish. Songs p. 508 ".

Text history

The plot remained the same from the first to the last edition, with individual linguistic details being smoothed out. From the 2nd edition, the newborn prince is only referred to as a boy, in accordance with the general avoidance of such foreign words in Grimm's fairy tales. It is added that the hero tries to appease the angry woman. The 3rd edition smooths out some somewhat unclear formulations: The merchant goes “out into the field” (instead of “out there”), did not “know what he was promising” (instead of “without his knowing”). There is no play on words, according to which the wish in front of the city "also ends in front of it, but not in it", the hero is simply "there, and wanted to go to the city". The queen takes "her child" (instead of "her prince"). The description that the invisible person becomes "a fly", which does not fit well with the final scene, is avoided. The guests are “present” (instead of “there”). From the 4th edition onwards, the guests not only want to catch the hero, they also attack him. Only in the 5th edition does the just promised son hold on to "legs" (instead of "benches"). The 6th edition describes something more lively, the water of life is in a bottle, the cunning one takes the ring before she pulls her foot away. The man armed with the magic thinks of his wife and child (which probably excuses the theft). At last the heads roll, but it was omitted that “everything is in the blood”. The depiction of violence is thus softened. What remained was the magic formula “Get your head down, just not mine”, emphasized in its drastic form by lowering the language level (cf. for example KHM 126 ).

The first edition already contained idioms such as “get something out of your thoughts”, “take something to heart”, “he let God be a good man”, “little people have a clever mind”, which has to be used in the 6th edition Money in “boxes” (cf. KHM 31 , 181 ), “he was in good spirits again” (cf. KHM 20 , 36 , 54 , 60 , 101 , 177 ).

The magic tale is structurally similar to the Italian poem Historia de Liombruno , late 15th century.

According to Christoph Schmitt , the military narrative milieu is also emphasized in the nights of torture compared to the patience test of the search hike. The King of the Golden Mountains has been the leading version of the 1st subtype of AaTh 400 since H. Holmström's treatise from 1919, which plays no role outside of Europe.

See the devil's godfather in Ludwig Bechstein's German book of fairy tales from 1845.

interpretation

It is typical of a fairy tale that an often simple but honest and fearless man goes out and wins a king's daughter by passing some kind of test. Luck saves him again and again when he gets into trouble. His own mistakes, the use of the wish ring, the theft of the miraculous gifts, he commits rather accidentally and unintentionally. His parents are more simple-minded, and the hero has to encourage his father and argue with the evil one that he betrayed his father. They give shelter to a poor shepherd, but don't believe him because of his simple clothes. The woman is evidently a sorceress , as indicated by her snake shape (cf. KHM 16 ). She has magical items like the water of life and the wishing ring. She suspects the future when her husband visits her parents and is insidious when she appears to forgive him and then avenge herself.

The initial conflict - the child cannot leave yet, the money has "perished" - is described in a similar way as later in KHM 181 The Mermaid in the Pond ( Jephtha motif, cf. KHM 3 , 12 , 31 , 55 , 88 , 108 , 181 ). Like money, the son is supposed to sink into water, but is healed with the water of life . The cursed waited twelve years, so since the devil's pact. The repentant father "kept silent" before the black man, like the son with the twelve black men. At the beginning the father takes the loss "to heart", the son's heart is moved when he finally thinks of the father who does not recognize him because he is poor. The giants also share their father's legacy. The hero "gave short words" and beheads the intruders (ATU 974 homecoming of the husband ) like the devil before him.

In terms of depth psychology, Hedwig von Beit interprets the black male as a shadow of the unconscious, which draws energy from the one-sided materially oriented consciousness (Kaufmann). The child, who is mistaken for an animal, crosses the river as a border between the worlds, also illustrated in the turning boat under which it does not drown. City, castle and snake are the anima (female core), whose enchantment apparently corresponds to the age of the hero. She wants life (water of life), but if she is forcibly dragged into consciousness, she shows her angry face. All that remains is an empty, earth-bound shell (Schuh, cf. KHM 133 ). The three tormented nights (see also KHM 93 , 113 , 121 ), which are reminiscent of ancient mystery cults or shaman's consecration, are repeated in the three giants that the hero can outsmart (see KHM 93 , 193 , 197 ), but the conflict between one-sided Actors is not resolvable.

Walter Scherf sees a redemption conflict: money is more important to the father than the son, he has to expose him, who believes he is independent, but later seeks pointless confrontation with him. Grimm's narrator continues suspiciously and implacably. Scherf compares Johann Wilhelm Wolf's The Iron Boots and Ulrich Jahn's The Vendace . In all European versions, the emphasis on another world shimmers through.

literature

- Jacob Grimm , Wilhelm Grimm : Children's and Household Tales. Complete edition . With 184 illustrations by contemporary artists and an afterword by Heinz Rölleke. 19th edition. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf / Zurich 2002, ISBN 3-538-06943-3 , pp. 464-470 .

- Jacob Grimm , Wilhelm Grimm : Children's and Household Tales. With an appendix of all fairy tales and certificates of origin not published in all editions . Ed .: Heinz Rölleke . 1st edition. Original notes, guarantees of origin, epilogue ( volume 3 ). Reclam, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-15-003193-1 , p. 178-181, 482 .

- Hans-Jörg Uther : Handbook to the "Children's and Household Tales" by the Brothers Grimm. Origin, effect, interpretation . de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019441-8 , pp. 211-213 .

- Walter Scherf: The fairy tale dictionary. Volume 1. CH Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-39911-8 , pp. 710-717.

- Hedwig von Beit: Symbolism of the fairy tale. Bern, 1952. pp. 387-402. (A. Francke AG, publisher)

Web links

- Märchenlexikon.de on Swan Maiden AaTh 400

- Märchenlexikon.de to giants arguing about magic things AaTh 518

- Märchenatlas.de on The King of the Golden Mountain

Individual evidence

- ↑ Lothar Bluhm and Heinz Rölleke: “Popular speeches that I always listen to”. Fairy tale - proverb - saying. On the folk-poetic design of children's and house fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm. New edition. S. Hirzel Verlag, Stuttgart / Leipzig 1997, ISBN 3-7776-0733-9 , pp. 109-110.

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Uther: Handbook on the children's and house tales of the Brothers Grimm. de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019441-8 , pp. 211-213.

- ↑ Christoph Schmitt: Man in search of the lost woman. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 9. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1999, ISBN 3-11-015453-6 , pp. 195-210.

- ↑ by Beit, Hedwig: Symbolik des Märchen. Bern, 1952. pp. 387-402. (A. Francke AG, publisher)

- ↑ Walter Scherf: The fairy tale dictionary. Volume 1. CH Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-39911-8 , pp. 710-717.