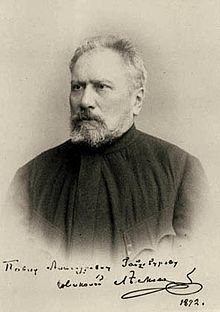

The left-handed (Nikolai Leskov)

The left-hander , also The Steel Flea ( Russian Левша , Lewscha), is a story (more precisely: Russian literary scholars talk about a Skas in the case ) by the Russian writer Nikolai Leskow , which appeared in 1881 in Aksakov's Slavophile newspaper Rus (Russia) in Moscow .

Using the example of a gunsmith , Leskov shows that Russia does not appreciate its specialists.

content

After the consultations in Vienna, Alexander I - who has now traveled to Central Europe - admires a different wonder every day in England . In the Kunstkammer the ruler can hardly get enough of an English pistol . The ataman General Platow - following the ruler's entourage - unscrews the handgun and takes out the lock. It says "Ivan Moskvin in the city of Tula ".

The hosts must do something about the embarrassment. The next day, they present the Tsar with a tiny steel flea in their new art chamber. With the praise “You are the first masters in the whole world, and my people understand absolutely nothing compared to you” the ruler bought the toys from the hosts for a million in silver fives.

Alexander I dies. The flea falls into the hands of Nicholas I. The new ruler asks the now aged Platov to check this mysterious precision mechanics. Platow hands the flea from England to the three most skilled Tula armories. One of the three masters is the cross-eyed left-hander. Platov travels from Tula to his silent Don . When the old man arrives in Tula after a fortnight and inspects the flea, he has a fit of anger. It seems that all three Masters have put their hands in their laps for two weeks. The left-hander - in rags, as Russian experts were dressed at the time - has to go to an audience in Petersburg .

Dusty, unwashed, but fearless, the poorly dressed left-handed man steps before the tsar and explains to the ruler that inspection of a heel of the flea through the miniscope will reveal the secret. The laughing Tsar cannot help but be amazed. The Tula people shod the flea with horseshoes. The left-hander goes one better. He forged the horseshoe nails by hand.

Freshly bathed and dressed in new clothes, the left-handed man and his flea are sent to England. The newcomer is astonished to discover that the professionals in England are all properly dressed and are even receiving professional training. The English recognize the talent of the guest and want to keep him. Nothing to be done - the left-hander gets homesick for Russia. The reception of the now sick at home is anything but appropriate. In Petersburg he is only accommodated in a hospital, which usually houses the dying of unknown class. The left-hander dies. Before his death, he asks the attending physician to deliver an important message to the Tsar regarding the cleaning of weapons. The news stuck with the war minister, Count Chernyshov , who was biased against experts . So the Russians lose the Crimean War .

Adaptations

- 1964 Soviet Union : The Left-Handed , animated film by Iwan Iwanow-Wano .

- 1986 Soviet Union, Lenfilm : Der Linkhander, feature film by Sergei Ovtscharow with Nikolai Stozki in the title role.

reception

- Eberhard Reissner wrote in 1971: “The contemporary commentators were divided on the question of whether the story of the left-hander glorified or disparaged the Russian people. Finally, Leskov declared that neither one nor the other was his intention. However, the left-hander may be seen as the embodiment of the good qualities of the Russian people ... At the same time, the writer wanted to denounce the backwardness of his homeland. "

- Rudolf Marx calls the text “a prose poem that has become a folk tale and is characterized by high-spirited, sometimes folk etymological distortions of language”.

German-language editions

- The steel flea. Translated from the Russian by Karl Nötzel . P. 7–66 in Nikolai Lyesskow: The beautiful Asa. The steel flea. The ready to fight. Three stories. 237 pages. Verlag Karl Alber , Freiburg im Breisgau 1949

- The left-handed. The story of the cross-eyed left-hander from Tula and the steel flea. German by Hertha von Schulz. P. 124–165 in Eberhard Reissner (Ed.): Nikolai Leskow: Collected works in individual volumes. The juggler pamphalon. 616 pages. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1971 (1st edition)

- The left-handed. The story of the Tula cross-eyed left-hander and the steel flea. German by Ruth Hanschmann. Pp. 205-251 in Nikolai Leskow: The way out of the dark. Stories. 467 pages. Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Leipzig 1972 (Dieterich Collection, Vol. 142, 3rd edition)

- The left-handed. The story of the Tula cross-eyed left-hander and the steel flea. German by Ruth Fritze-Hanschmann. P. 103-140 in Nikolai Leskow: The specter. Stories. 272 pages. Gustav Kiepenheuer, Leipzig 1982 (Die Bücherkiepe, 1st edition)

Output used:

- The left-handed. The story of the cross-eyed left-hander from Tula and the steel flea. German by Hertha von Schulz . P. 540–579 in Eberhard Dieckmann (Ed.): Nikolai Leskow: Collected works in individual volumes. 4. The unbaptized priest. Stories. With a comment from the editor. 728 pages. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1984 (1st edition)

Web links

- The text

- Wikisource : Левша (Лесков) (Russian)

- online at Lib.ru / Classic (Russian)

- online at RVB.ru (Russian)

- Audiobook as 68 min mp3 on YouTube (Russian)

- Text, film, animation and audio book online at leskov.org.ru (Russian)

- Entry in the Laboratory of Fantastics (Russian)

- Entries in WorldCat

Remarks

- ↑ The model for the left-hander is said to have been Alexei Michailowitsch Königin (1767–1811, Russian Алексей Михайлович Сурнин ).

- ↑ One of the funky formal elements is the corruption of technical terms and other foreign words. For example, the Russians look at the flea through the miniscope (for microscope - in the original мелкоскоп instead of микроскоп).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Russian Русь

- ↑ Edition used, p. 543, 7. Zvo

- ↑ Edition used, p. 546, 1. Zvu

- ↑ Russian Левша (мультфильм)

- ↑ Animated film 42 min by Iwanow-Wano on YouTube

- ↑ Russian Левша (фильм, 1986)

- ^ Reissner in the follow-up to the 1971 Leskow edition, p. 599, 3rd Zvo

- ↑ Rudolf Marx in the introduction to the 1972 Leskow edition, p. 45, 5th Zvu