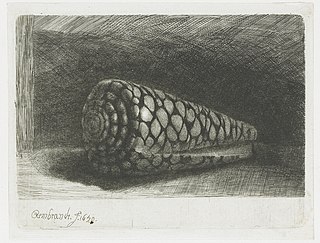

The Conus Marmoreus mussel

| The Conus Marmoreus mussel |

|---|

| Rembrandt van Rijn |

|

| State 1/3 , 1650 |

| Etching, drypoint, 9.7 cm × 12.9 cm |

| Rijksmuseum Amsterdam |

|

|

|

| State 2/3 , 1650 |

| Etching, drypoint, grave mark, 9.7 cm × 13.1 cm |

| Rijksmuseum Amsterdam |

|

|

|

| State 3/3 , 1650 |

| Etching, drypoint, grave mark, 9.6 cm × 13.2 cm |

| Rijksmuseum Amsterdam |

The Conus Marmoreus shell or the marble cone snail is an etching by the Dutch painter and graphic artist Rembrandt van Rijn from 1650. It is characterized by great attention to detail, but Rembrandt hasdepictedthe snail shell of the marble cone (Conus marmoreus) in a mirror image. The etching has come down to us in three plate states, of which the third state is only known as a unique piece in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam . The other two states are each preserved in several copies. The Conus Marmoreus shell is one of Rembrandt's rare etchings and can achieve prices in the six-figure range at auctions.

description

The etching shows a marble cone (Conus marmoreus) , which lies across the picture surface with the tip pointing to the right. The opening is below and on the left side the concave, stepped thread is visible. The figure is 6.4 inches long. With a shell length of fully grown snails of five to 15 centimeters, a reproduction of Rembrandt's original in its original size can be assumed. Rembrandt apparently transferred the snail shell to the copper plate as it was before him. This resulted in a mirror-inverted left-handed reproduction in the print. The casing of the marble cone is always twisted to the right, so the etching is not a true-to-life representation. Rembrandt probably thought the orientation of the snail shell was unimportant. The snail casts a shadow to the lower left. In the lower left corner are the signature and date “Rembrandt f. 1650 “mounted in the plate.

The first state is a drypoint over a sketch executed as an etching. It shows the shell of the snail against a white background. The upper edge of the snail shell looks unfinished, with several gaps in the outline. This repeatedly led to the determination that the first plate state is an unfinished work. In fact, decades later, Isaac Newton proved that a light-dark sequence makes the white appear literally protruding. Rembrandt probably reproduced the impression of the picture realistically.

The contradiction in the shadow cast by the snail hovering in the empty space was possibly the reason for Rembrandt to hatch the background for the second state. In this way he created the impression that the snail was lying on a shelf. In addition, Rembrandt used the burin to reduce the contrasts on the surface of the snail's shell.

For the third condition, which is preserved in a single print in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam , Rembrandt reworked the thread of the case with the burin. The spiral, which appears rather flat in the second state, is thus worked out more stepped.

background

The Conus Marmoreus shell is one of Rembrandt's few still lifes and the only one among his etchings. Deviating from the title of the etching, which uses the colloquial meaning of “shell”, the marble cone shown is not a shell in the biological sense, but a cone snail. The misleading title was probably given at a later date. The scientific species name Conus marmoreus is correct, but it was only determined by Carl von Linné in 1758 . With Rembrandt's contemporaries, cone snails were known as Hertshoorn (German: "Hirschhorn").

Exotic mussel shells and snail shells that Dutch seafarers brought back from their travels were popular collectibles in Holland during the Golden Age and were often included in contemporary chambers of curiosities . Due to their beauty and rarity, they were understood as a link between nature and the arts or as their fusion. For the up-and-coming bourgeoisie, gathering such objects and working with them was an opportunity to enhance their own value, the opportunity to enter the world of the princes with their chambers of curiosities and naturalists. So at the beginning of the 17th century snail shells became a possible attribute of the enlightened citizen, as in Hendrick Goltzius ' painting Portrait of the Shell Collector Jan Govertsen van der Aer (1545–1612) .

For some collectors, the shells became an obsession , and they were sometimes bought for astronomical sums. This was criticized as early as the early 17th century. In Roemer Visscher's Sinnepoppen , a collection of emblems , first printed in 1614 , a motto over an engraving with various shells and snail shells reads: “Tis misselijck waer een geck zijn gel aen leijt” (German: “It is crazy what a fool spends his money on "). The following picture shows a tulip and relates in a similar way to the tulip hobby , which culminated a few decades later in the tulip mania : "Een dwaes en zijn Gelt zijn haest ghescheijden" ("A fool and his money are hastily divorced").

Conch shells and snails were popular motifs for visual artists. The Dutch still life painter Balthasar van der Ast depicted them in numerous of his works, mostly in combination with fruits, flowers, insects and other animals. Often, because of their beauty and fragility, they appear as symbols of the transience of everything earthly on vanitas still lifes . The Bohemian artist and engraver Wenzel Hollar made a series of engravings of various snails, including the Emperor cone (Conus imperialis) . Hollar's works were exact replicas that met the highest scientific standards. Rembrandt's Conus Marmoreus shell reveals Rembrandt's efforts to create a representation “after life”. But it also becomes evident that for him the play of light and shadow on the rounded surface of the snail shell was in the foreground. Hollar's engraving was often viewed as a direct model from Rembrandt. In fact, his role was limited to showing Rembrandt the possibility of depicting a single snail.

Rembrandt had set up his own extensive cabinet of curiosities, the objects of which were often depicted on his works. At an auction on March 9, 1637 in the Prinsengracht , Rembrandt bought a "shell" for eleven guilders. That was an extremely large amount. At the same auction he bought prints for 92.10 guilders, only one of which, according to Raphael , was twelve guilders more expensive than the “shell”. Rembrandt was known for buying prints at auctions at high prices and for warding off all possible interested parties with an unnecessarily high entry-level bid. According to his own account, he did this to show his fellow artists his respect. The inventory of his household, which was drawn up in July 1656 on the occasion of his insolvency, shows under item 179 “A large amount of mussels, seaweed, casts from life and many other rarities”. With the sea plants corals are meant.

- Sea slugs in 17th century Dutch fine arts

Balthasar van der Ast, Sea snails and fruits , 1620s, oil on oak, 29 × 37 cm, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister , Dresden

Balthasar van der Ast, Still Life with Snails and Autumn Croissants , ca.1630, oil on copper, 10.3 × 17.2 cm, Centraal Museum Utrecht

reception

The English doctor and naturalist Martin Lister published his Historiae Conchyliorum between 1685 and 1692, a work that contained more than 1000 images of snail shells. Most of the copper plates in the illustrations were made by Lister's daughters Anne and Susanna Lister . For the plate for Plate 787, the marble cone, Anne Lister used Rembrandt's etching as a template, but mirrored it again so that a correct representation was available. Since Lister had previously dealt with the direction of rotation of the worm housing, there is no doubt that the change is a deliberate correction of Rembrandt's mistake. Lister bequeathed the plates to the University of Oxford . In 1760 they were used again by William Huddesford for a new edition of Lister's Historiae Conchyliorum . Today the plates are in the Bodleian Library . The Lister's sketchbook is also kept there, in which a copy of the Conus Marmoreus shell is glued.

In connection with the not infrequent in digitally created productions laterally inverted image of snails as a supposed Schneckenkönig is The Shell Conus Marmoreus occasionally mentioned as a historical example.

Of the three plate states, the third state is only known as a unique item in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam . Five of the first state and eleven of the second are in public collections. In addition, there are a few privately owned copies; but they are extremely rare. Once the Conus Marmoreus mussel appears at auction, it can achieve a price in the six-figure range.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Werner Busch: Rembrandt's shell - imitation of nature? A methodical lesson . In: Bettina Gockel (Ed.): From Object to Image. Pictorial processes in art and science, 1600-2000 . Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-05-005662-3 , pp. 93–121 ( uni-heidelberg.de [PDF; 8.4 MB ]).

- ↑ a b Karin Leonhard: About left and right and symmetry in the baroque . In: Stephan Günzel (Ed.): Topology. For the description of space in cultural and media studies . Transcript, Bielefeld 2007, ISBN 978-3-89942-710-3 , p. 135-152 .

- ↑ a b c Holm Bevers: 29. The Shell (Conus marmoreus) . In: Rembrandt. The Master & his Workshop. Drawings & Etchings . Yale University Press, New Haven, London 1991, ISBN 0-300-05151-4 (English).

- ^ A b H. Perry Chapman: Rembrandt on display. The Rembrandthuis as portrait of an artist . In: Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art / Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek Online . tape 65 , no. 1 , 2015, p. 202-239 , doi : 10.1163 / 22145966-06501009 (English).

- ^ A b Karin Leonhard: Shell Collecting. On 17th-Century Conchology, Curiosity Cabinets and Still Life Painting . In: Karl AE Enenkel, Paul J. Smith (Eds.): Early Modern Zoology. The Construction of Animals in Science, Literature and the Visual Arts . tape 1 . Brill, Leiden, Boston 2007, ISBN 978-90-04-13188-0 , pp. 177-216 (English).

- ↑ Roemer Visscher: the sense Poppen . Willem Jansz, Amsterdam 1614 (Dutch, digitized ).

- ↑ No. 51. Rembrandt as a buyer in art auctions . In: Cornelis Hofstede de Groot (ed.): The documents about Rembrandt (1575-1721) . Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague 1906, p. 116-118 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ No. 169. Rembrandt's inventory . In: Cornelis Hofstede de Groot (ed.): The documents about Rembrandt (1575-1721) . Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague 1906, p. 189–211, inventory no. 179 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ RW Scheller: Rembrandt en de encyclopedische kunstkamer . In: Oud Holland . tape 84 , no. 2/3 , 1969, p. 81-147 , JSTOR : 42712348 (Dutch).

- ^ Simon McLeish: The Lister copperplates. In: The Conveyor. December 9, 2010, accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ CJPJ (Kees) Margry: Slakkenkoning as digitaal artefact . In: Spirula . tape 358 , no. 1 , 2007, p. 129–133 (Dutch, natuurtijdschriften.nl ).