The sea

The Sea ( English original title The Sea ) is a novel by the Irish writer John Banville from 2005.

The 18th novel by Dublin- based writer and literary journalist John Banville is about the aging art historian Max Morden. After his wife Anna dies of cancer, he returns to the Irish seaside town of his childhood, where he always spent his summer holidays. There he tries to process positive memories such as the first experience of love and eroticism, but also traumatic events by writing down his memories in a detailed and narcissistic manner in language rich in images.

With his first-person narrator Max Morden , John Banville creates a dense atmosphere in the various time levels that are repeatedly blurred in Mordens' monologue . He lets the boundaries between real memories and fantasies and between consciousness and the unconscious become fluid. The melancholy mood is reinforced by the poetic, gloomy and at the same time fascinating atmosphere of the sea.

John Banville received the Man Booker Prize 2005 for the novel . The novel is a "masterful study of grief, memory and love," said Booker jury chairman Prof. John Sutherland.

content

The art historian Max Morden, the first-person narrator of the novel, lost his wife Anna to cancer a year ago. In his growing desperation, he returns to the seaside resort of Ballyless, where he also suffered a traumatic loss as a child. When he was about ten years old, he had spent his vacation there with his parents who fell out. There he got to know the wealthy Grace family, who for him embodied all of his erotic and social dreams, appeared to him as gods of ancient times on the social Olympus. The Graces' two children, the twins Myles and Chloe, become his playmates.

If little Max's erotic fantasies are directed towards his mother first, he finally falls in love with Chloe, who is the same age, and exchanges his first kisses with her in the dark cinema. Chloe and her dumb brother Myles are always full of puzzles for Max. After Chloe Max allowed a first sexual touch in a beach house and was surprised by the housekeeper Rose, Chloe and Myles go to the water without a word, swim further out and finally drown. Max's first attempt to escape his family fails. A short time after the disaster, his father leaves the family forever, the boy grows up in poor circumstances with his frustrated mother.

The second narrative level describes the marriage story of Max and Anna. As the child of a father who has dubiously got money and who dies shortly after the wedding, Anna Max enables the life of a private scholar. The largely harmonious marriage of the two is confirmed by the cancer diagnosis Dr. Todds is destroyed, all security is broken, and a phase of life full of destructive doubts begins for Max.

A year after Anna's death, Max decides to stay in a guest house in Ballyless, the holiday resort of his childhood. The guesthouse turns out to be the former vacation home of the Grace family, run by their housekeeper at the time, Rose. Max pursues the losses of the past in lonely walks and reflections and increasingly loses contact with reality. Dreams, unconscious and present experiences mix more and more. Max eventually begins to drink excessively until he breaks down.

subjects

Love and impermanence

In addition to grief and love, John Banville places the theme of “transience” at the center of the novel.

“My novel is about how quickly the present turns into the past. And it's also about how much power the past has over our lives. Anyone who thinks about the past realizes very quickly that it carries much more weight than the present on a dream-like level. "

After Banville, the hero of the novel, Max Morden, travels to the holiday resort of his childhood to counter the grief for his deceased wife. The attempt to bring the experiences of his childhood back to life brings the first erotic experiences and pure experiences of his childhood to light. This is exactly where Morden is looking for the point from which he can regain control of his life.

Banville's “Die See” portrays the aged narrator's review of his life. The view is sharpened by the traumatic experience of death, which makes the world appear in a different light. Despite this sharpness, the memory remains unreliable. Max Morden realizes this with horror when he returns to the places of his childhood.

"When I saw the reality, the blatant, self-satisfied reality, take possession of the things I remembered and shake them until they were the shape that it looked like, I felt almost panicked."

Max Morden's journey into the past combines the two great experiences of loss in his life. The fading of memories is like a repetition of the original loss.

“I thought of Anna. I force myself to think of them, these are the kinds of exercises I do. It stuck into me like a knife, and yet I am already beginning to forget it. Your image is already beginning to wear out in my head. "

Banville emphasizes that the narrator Max Morden differs from earlier fictional characters mainly in that he appeals to the sympathy of his fellow men in his deep sorrow.

The death

The central theme of the novel is death . Not only does the narrator's wife die, his two childhood friends also drown.

“Well, death is always superfluous and unmotivated. That's the crux of the matter, he always hits us unprepared. So, the book called for more than this one death, just like life. With the death of the children I wanted to represent exactly that, death has no meaning. Of course we take it very seriously, it has to be. But it's not serious, it means the end of certain creatures, that's almost coincidental. And at the end, in this last scene, in which Max, the child is standing in the sea, and this strange wave is approaching, he asks himself, was that something special. And he says no, it was just a shrug from the indifferent world. "

Banville explicitly refers to Martin Heidegger , for whom death was a determining factor in human existence. It is only from the double experience of death that the immense intensity with which Max Morden experiences the world grows.

"Maybe the whole of life is nothing more than long preparation for the moment of departure."

Beyond the constitutive meaning of death for human existence, the novel asks what remains of people. Max Morden develops a position of radical transience, the erotic Connie Grace becomes "a bit of dust and dried-up marrow". Morden sees the survival in the memories of the lovers as scattering "in the memory of the many", which only lasts as long as they continue to live. Max Morden sees no religious hope.

“I am not considering the possibility of an afterlife or of a deity who has the ability to grant such a thing. If you look at the world he created, it would be disrespect to God to believe in him. "

painting

After Banville, the paintings by the French Pierre Bonnard had a great influence on the novel . Bonnard had painted his wife again and again, always young, often as a nude in the bathroom, even after her death. Banville sees a deep connection here to his fictional character Max Morden, who has also sought strength against the loss of his wife in the past. Banville, for example, had Max Morden write a biography of Bonnard without luck. The connection between the painting of French symbolism goes deeper, trying to linguistically take a similarly intensive look at the objects.

The self-image of the narrator Max Morden appears to be shaped by a portrait of Van Gogh:

“... as if he had just been submerged as a punishment, receding forehead, dented temples and hollow cheeks, sunken from hunger; he looks obliquely out of the frame, suspicious, angry and at the same time full of foresight, like someone who expects the worst, which he has every reason to. "

Like Van Gogh in the portrait, the narrator grows a surprisingly red beard on his journey into the past. Other aspects of the portrait also enter into the self-portrayal of the narrator Max Morden, the rosacea , the inflammation of the eyes; it appears as if Banville had begun to look at van Gogh's self-portrait like a mirror image while writing the novel.

Describing the past also appears as a form of painting because Max Murden's memory does not create moving pictures, but rather still lifes of the past, documents from a bygone era frozen in painting. The great experiences of the past do not appear in Banville's novel as a relived action in time, but as an accumulation of frozen fragments and details.

“It was a splendid, oh yes, a really splendid autumn day, all the copper and gold tones of Byzantium under an enamel-blue Tiepolo sky, the landscape completely varnished and glazed, didn't look like the original at all, but rather like its own reflection in the still water of a lake. "

A typical image for painting the frozen past is the portrayal of the almost statuesque-looking Grace family at a picnic. Another scene reminiscent of painting describes Rose washing Connie Grace's hair in the garden with the water from an old rain barrel.

“It cannot be overlooked that she has only just got up, her face looks rough in the morning light, like a sculpture that is still missing the finishing touches. She stands in exactly the same pose as Vermeer's maid with the milk jug , her head and left shoulder tilted forward, one hand arched under Rose's heavily falling hair, while she and the other pour a thick, silvery gush of water from a chipped enamel jug pours. "

It is above all Connie Grace who attracts Max Morden to such painted memories. The literary processing of classic paintings is an obvious design principle. The vocabulary often corresponds to that of a picture description. But also Chloe and Rose, the two other heroines of “the salt-bleached triptychthat summer “encourage new language paintings. It is Rose, “whose picture is most clearly drawn on the wall of my memory. I think that's because the first two characters in this play, I mean Chloe and her mother, are entirely my work, while Rose comes from another, unknown hand. I get closer and closer to the two, the two Graces, now to the mother, now to the daughter, apply a little paint here, weaken a detail there ... "

"He admits his lack of real talent: precisely the source of his eagerness to impress by the acuity of his visual impressions. For this "middling man", everything exists to end in one of the static tableaux of which his reminiscences are made. "

“The narrator admits that he lacks real talent: this is precisely the source of his eagerness to impress with the sharpness of his visual impressions. For this mediocre man everything exists only to end in the static still lifes that make up his memory. "

The other references to painting are numerous. With her curved nose, Rose reminds Max of a late portrait of Picasso, which shows a frontal perspective and profile at the same time. Sometimes he thinks of a Duccio Madonna when he sees her. Max Morden's daughter remembers him with her disproportionate figure on one of the drawings by John Tenniel for Alice in Wonderland .

Literary form

Recourse to mythology

Banville takes up various motifs, especially from Greek mythology. The narrator's mental journey into the past appears as an attempt to bring the past and the dead to life through intense memories.

“A year ago today, Anna and I had to visit Mr. Todd for the first time in his practice. What a coincidence. Or not, maybe; Are there any coincidences in Pluto's realm, through whose untrodden expanse I mislead Orpheus ? Twelve months already, after all! I should have kept a journal. My diary of the year of the plagues. "

Especially the admired "Grace" family (= "grace", "charm") and their children appear to him as "gods". Divinity not only refers to the high social position of the “Graces”, but also to ancient ideas of mystery and eroticism. As a boy Max was very interested in the Greek sagas and was fascinated by the metamorphoses of the Greek gods. He connects the idea of nudity with the ancient images of gods, associates corresponding representations in Michelangelo and other masters of the Renaissance . The divine graces seduce the Christian educated Max to the "sin of looking".

To the admiring Max, Mr. Grace appears at the same time as a satyr and "as Poseidon of our summer", "just like the old father himself". His wife Connie as a maenad , as "lolling Maja ", as " avatara ", d. H. as an Indian deity descended from heaven. The nanny Rose embodies Ariadne on Naxos for the young Max Morden , Chloe appears as a pan figure and her mute brother Myles with the webbed toes (“Identifying features of a little god, sky clear”; Die See, p. 55) as an evil goblin, as a poltergeist .

The novel emphasizes the mythical trait of narrative wanderings through the realm of the dead, the lost past, when it lets the narrator speak from the perspective of the revenant.

“Just now someone was walking over my grave. Anyone. "

Max Murder's growing fear appears to him in a classic form, as life “in a twilight underworld”, the “cold coin for the crossing in my hand, which is already cold”.

The narrator often makes the connection to mythology through the sea. Indifferent to the fate of the living and the dead, it appears as a timeless connection between the mythological and the real world.

“The small waves in front of me on the bank spoke in a lively voice, eagerly whispering something about an old catastrophe, perhaps the fall of Troy or Atlantis' downfall. Nothing but edges, brackish and shimmering. Pearls of water burst and fall as a silver chain from the corner of a rudder blade. In the distance I see the black ship, imperceptibly rising up out of the mist from second to second. I'm there. I hear your siren singing. I'm there, almost there. "

But it's not just classical Greek mythology that fascinates John Banville. Kneeling Chloe with Myles and Max sitting behind her reminds the narrator of an Egyptian sphinx; he sees himself as a collector of material for an Egyptian book of the dead.

The uncanny in Freud's sense comes from the return of the known. It is the change in what used to be homeland that alienates and distorts.

In the face of death, the curtain that separates the rational world of the present from fears, dreams and myths tears. If Anna's doctor, Mr Todd, speaks of "promising therapies and new drugs" after the cancer diagnosis, it sounds like "magic potions" and " alchemy " to the narrator , he hears the "silent rattle of the leprosy bell". Out of the absolute threat to life "a new variety of reality" grows, the absolute indifference of the material world towards the suffering of people proves.

Speaking Names

Meaningful names emphasize the fictional character of the story. This is particularly clear from the fact that even the first name of the narrator is an invention, that we do not even find out his real name. But the names of other characters and places are also identified as the narrator's inventions:

"Rose, let's give her a name too, poor Rose ..."

“The car came out of the village and sped to the city, which is twenty kilometers from here; I will call her Ballymore. The town is called Ballymore and this village is called Ballyless, sometimes more, sometimes less Bally, silly ... "

The slang word “bally” (= “damned”, “cursed”) refers to the tragedy to be expected, as does the names of some of the characters. “Mr Todd” is the name of the doctor who pronounces the death sentence on Anna, the narrator's wife, “Max Morden”, alliterating the narrator who is haunted by feelings of guilt. It is no coincidence that the associations with “death” and “murder” run across German; Banville refers in an interview to the fundamental meaning of death for Martin Heidegger and Paul Celan . Banville plays with the connotations of these terms, for example when he calls the cancer in Anna's belly "the big baby t'Od".

The dubious Colonel, who tries in vain to get closer to the hotel manager, is called "Blunden" ("to blunder" = to make a gross mistake). The attractive, young housekeeper Rose becomes the elderly, soured hotel landlady "Miss Vavasour".

Banville's technique, also known from earlier novels, of charging the names of his characters with connotations through German, is not only met with enthusiasm among reviewers.

"Max and his wife go to visit an oncologist named Mr. Todd, and Max says," This has to be a bad joke on the part of polyglot fate. " If you (a) know that "tod" is the German word for death (I had to look it up) or (b) like such erudite word play, you'll love what Banville is doing here. If your reaction is, "what a pretentious jerk," you've summed up Max pretty well, but you might want to pick out a different book. "

"Max and his wife visit an oncologist named Mr. Todd and Max says:" A tasteless joke of a polyglot fate. "If you a) know that" Tod "is the German word for" death "(I had to look it up.) or b) like such learned puns you will love what Banville is doing here. If your reaction is, "What a noble kitsch!", Then you get to the point Max quite well, but you should feel like picking up another book. "

David Thomson also sees the play on words with Mr. Todd as herald of the fatal diagnosis as a failed attempt to develop a humorous play on the subject of death.

Narrative technique

Apparently the reader overhears the inner monologues of the narrator Max Morden unnoticed over long stretches of the novel , irritated by incomprehensible allusions, surprising mixes of times and places. But again and again this role of the reader as a secret listener is broken, as the narrator of Banville's novel reflects as a writing author, clearly emphasizing the fictionality of the memory work.

“How old were we then, ten, eleven? Let's say eleven. That's enough. "

“And why should I, unlike every melodrama who has run along, shut myself off from the demand that the story needs a really surprising twist at the end? (After all why should I be less susceptible than the next melodramatist to the tale's demand for a neat closing twist?) "

This creates a strange look at the memory work of the narrator Max Morden, who suddenly speaks from the perspective of the author, “creating, not remembering”, as John Crowley writes in his review in the Washington Post.

Another typical feature of Max Morden's narration is the joy of aphorisms that get to the heart of his position philosophically or drastically.

"There are moments when the past has such tremendous power that you almost think it can wipe you out."

"The tea bag is a terrible invention, with my perhaps a little over-sensitive look it always reminds me of something left behind in the toilet bowl out of carelessness."

The narrator very often uses literary quotations, e.g. a. by Yeats, Keats, Milton, Tennyson, Conrad, Shakespeare, Eliot and Stevens. The most frequent source of literary quotations in the novel, however, are the earlier works of the author himself. Banville uses names and characters as well as motifs.

"Is that what death is like, he wondered, whether that is how people begin to die, each time swimming a little further out until they no longer see any land, never more?"

style

The precise language of John Banville also catches the eye. The reviewers praise his brilliant style, reminiscent of Nabokov. Many aphorisms, puns and sentences are so skilfully formulated that they would enrich any collection of quotations.

The pointed person signs are also typical of Banville. In addition to fine observations, a cruel trait is also expressed, a sometimes cold look on the part of the narrator at his fellow men and himself.

“One of John Banville's skills as a stylist is to discern the alien at work in the human. 'One's eyes,' he writes, 'are always those of someone else, the mad and desperate dwarf crouched within.' ”

“One of John Banville's strengths as a stylist is to recognize what is alien in people. 'Our eyes', he writes, 'are always those of someone else, those of the crazy and desperate dwarf who hides within us.' "

Banville and his narrator Max Morden's choice of words is also demanding. If the English reader needs a dictionary in order to understand the connotations of the names of the actors based on German terms, the German reader will most likely need a dictionary when he reads the English edition. Even English reviews notice the often unusual choice of words and waves of unusual vocabulary.

The novel's central metaphor is “the sea”, a symbol for nature, which indifferently destroys human life with a murmur. It stands for the forces of nature that man is powerless to face, even if, as David Thomson explains in his review, it sometimes allows us to perceive them as a panorama of peace, beauty and tranquility.

Social worlds

Max Morden sees his poor origins as a burden; he set himself the goal of escaping the poor circumstances of his quarreling parents from an early age.

"If it had been in my power, I would have given my embarrassing parents immediate notice, would have burst like bubbles, my fat little mother with her bare face and my father, whose body looked as if it were made of lard."

Max's mother senses this rejection and reacts “hard and unmoved”, seeing his behavior as betrayal.

The world of his family is confronted in childhood with the world of the Graces. The big black limousine, a crumpled travel guide from the continent, the big holiday home mark a world worth striving for for little Max. Out of admiration, Max discovers divine traits and behaviors in the Graces.

As an adult, Max Morden once again meets a rich man with the father of his wife Anna, whose wealth seems to come from a dubious source. Unlike in childhood, Max succeeds in social advancement with the help of Anna's money. He becomes what he dreamed of as a child: a "man with useless interests and little ambition".

Time levels

The novel essentially combines three levels of time, which are, however, enriched again and again by further scraps of memory. The first narrative level is the perspective of the aging Max Morden one year after the death of his wife Anna. Another level is the narrative of Anna's marriage to her death. The third level describes an August in the narrator's childhood in which he met the Grace family and their children. First and third levels are set in the beach town of Ballyless.

In doing so, the narrator approaches the past to different degrees, sometimes remains authorial- distant, interpreted, suggests the future, but sometimes also takes the perspective of his past self. In such passages the story is told, and episodes long past develop new life.

Looks

The philosophy of gazes that the novel develops creates a complex web of reciprocal hidden and open observations.

“Twins: the gods, minor gods, strikingly similar, watch the narrator over the edge of the water. Gods or devils? Heavenly twins who "laugh like demons". Who is watching whom? I am seen, therefore I am. "

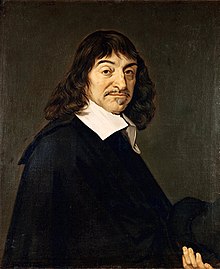

“I am seen, therefore I am.” This variant of Descartes “Cogito ergo sum” (“I think therefore I am.”) Is not the only philosophical allusion in the web of looks. It is above all the destructive and objectifying gaze of the other, as analyzed by Sartre in Das Sein und das Nothing , that the novel fills with life.

"Suddenly she was the center of the scene, the vanishing point where everything came together, suddenly she was the one for whom all the patterns and all the shadows had been arranged with such artless care: the white cloth in the shiny grass, the blue-green one , stooped tree, the fringed bracken, even the clouds that, high in the boundless, maritime sky above, tried to pretend to stand still. "

Only in the absolute strangeness of the “divine” graces does the narrator see himself, the social situation that characterizes him, his limitations. Chloe objectifies the narrator's world through its absolute otherness.

“I can say without exaggeration - well, a certain amount of exaggeration is definitely involved, but I still claim - that the world only became manifest for me as an objectively existing phenomenon through Chloe. Neither my parents nor my teachers nor the other children, not even Connie Grace, no one had been as real to me as Chloe before. And when it was real, suddenly I was too. "

Claudia Kuhland writes about the author accordingly: “He lives in seclusion near Dublin by the sea - John Banville, an Irishman who likes to sit between stools and loves provocation. The former journalist is something of an old-fashioned existentialist. "

The “topic of observing and being observed” is developed in the motif of the mirror. Increasingly, Max Morden sees himself as a parody of himself. The mirrors, which are too low due to his height, force him to adopt an attitude in which he is “unmistakably something of a hanged man”. The narrator not only sees himself in everyday mirrors, he also finds himself reflected in self-portraits by Bonnard and van Gogh.

"The transfiguration of the better-off Grace family - the lively Mr. Grace as" Poseidon of our summer ", the twins Chloe and Myles, the exciting Mrs. Grace who seemed so unreachable and desirable" like some pale painted lady with a unicorn and a book "- made the eleven-year-old Murder blind to the tragedy that was unfolding before his eyes, and still denied the aging narrator's reflection, clouded by the blurring of his memories, a clear view of the events behind the mirrors, in which Murden, above all, was always different saw only temporary versions of his own self. "

reception

John Banville's novel was largely positively discussed in the international feature pages, and the award of the Booker Prize was certainly one of the effects of this positive response. Above all, criticism hit the complexity of the work. Here are some voices:

“That John Banville got it right has long been attested by the critics. Much to his annoyance - because Banville wants to write for everyone - he has so far been a favorite of the feature pages. With his new fourteenth novel "Die See", which won the Booker Prize last year, he reached a large number of readers for the first time. "

“Banville's novel was arguably the most literary of the finale, so it was a remarkable choice. […] Critics hailed Banville as a great stylist and praised the novel for its eloquent meditations. An American admirer who asked him about the origin of his wonderful language, he referred a little surprisingly to the dictionary: "Webster, my dear."

“Death is always there beforehand in this novel. It stands at the end and at the beginning, and in his monologue John Banville approaches it from several locations and time levels. He writes to this great sucking nothingness, which in his youth, as the twins in an act of utter incomprehensibility, submerges him forever in the sea, and in old age as a depressed widower, like flotsam. And yet "Die See" is not a morbid old work, but a great reflection on loss, the limits of perception and the riddles of life. "

"They departed, the gods, on the day of the strange tide. You can tell from the first sentence, which you have to read out loud, that someone is serious about the language and the music. Every sentence in this book is tonally and rhythmically shaped, of which Christa Schuenkes' almost slag-free translation can at least give an impression. Banville is famous for the abundance of its pictures and details: the waves that come trudging up eagerly only to retreat like a flock of curious but also timid mice; the wind over the sea, tearing the surface of the water into sharply jagged, metallic shards; the cooling engine that clicks its tongue in disapproval. His prose is as masterful on the molecular level as it is in grand form. The game of assonance and the art of the epithet (read how he describes the eyes of teddy bears) are masterful; The wave-like gliding between four or five layers of time that stream through the Medusa-like narrator is masterful; The Plot-Mobile is masterful of Japanese grace and sophistication. "

“The Sea is, I'm afraid, a book that wo n't do the Man Booker Prize's reputation very good. Of course, the Man Booker Prize should not be awarded to a work based on its likely readership, it should be awarded for quality, and yet the Booker Prize winner will be one of the few titles that readers will buy this year. I discussed "Die See" three months ago and I'm afraid I can't remember anything except that it is set by the sea and I was impressed with the vocabulary. It's a nebulous, over-refined choice for the people of Hampstead, but hardly suitable for the normal reader. "

literature

- The Sea, Macmillan Publishers Ltd, June 2005, ISBN 0-330-43625-2 (original edition)

- Die See, translated by Christa Schuenke , Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-462-03717-X (original edition)

- Audio book: John Banville, Die See, narrator: Burghart Klaußner , 6 CDs, 2006, ISBN 3-491-91220-2

(The work received the Man Booker Prize 2005 and the Irish Book Award 2006.)

Secondary literature

- John Crowley: Art and Ardor. In: The Washington Post, November 13, 2005.

- Thomas David: The Tides of Memory. John Banville is at the height of his art in "The Sea". In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung of September 5, 2006 (NZZ review)

- Brian Dillon: Fiction - On the shore. In: New Statesman June 20, 2005

- Tibor Fischer: Wave after wave of vocabulary. Telegraph, July 6, 2005 ( online version )

- David Grylls: Fiction: The Sea by John Banville. In: The Sunday Times, June 12, 2005

- Lewis Jones: A ghost of a ghost. Telegraph May 6, 2005 ( online version )

- Claudia Kuhland: Remembered Love: The masterful novel “The Sea” by Booker Prize winner John Banville. WDR review from October 2, 2005

- Michael Maar: When the tide came, the gods left. A hurricane in a matchbox: John Banville's masterful novel “The Sea”. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of October 4, 2006, p. L6

- Ijoma Mangold: A little monster with dirty thoughts, what is me if not an oil stain on the waves? John Banville's sublime, fine novel "The Sea". In: Süddeutsche Zeitung of October 4, 2006

- David Thomson: Heavy With Grief and Mourning, Thick With Eccentric Verbiage. In: The New York Observer of November 13, 2005

- Yvonne Zipp: Dark musing by the Irish sea. In: The Christian Science Monitor of November 6, 2005

Web links

- Review notes on Die See at perlentaucher.de

- Deutschlandradio Büchermarkt, interview with Banville about the novel

- Mirror review

- Dipping a Toe in John Banville's "The Sea" The Literary Magazine 12 2005

- Collective link to English reviews

- further collective link to English reviews

References and comments

- ↑ a b c d John Banville, Interview in Deutschlandradio on September 25, 2006

- ↑ a b Die See, p. 100

- ^ "Instead, Max recounts with impossible exactness the passing of that summer and his own sensations of remembering. "Memory dislikes motion," Max says as he begins, with painterly care. (...) It seems that Max (and his maker) are engaged not in the working out of a character's actions through time - the usual business of a novel - but in the limning of moments of stillness, as a poem or a painting might. ”John Crowley, Art and Ardor, Washington Post, November 13, 2005; see. also Die See, p. 185

- ↑ Die See, p. 186

- ↑ Die See, pp. 186f.

- ↑ cf. for example the notes in the review by David Grylls: “Fiction: The Sea by John Banville”, The Sunday Times of June 12, 2005: “The narrator compares his face in a mirror to the last studies Bonnard made of himself and to an early self-portrait by Van Gogh. He notes that Rose variously resembles a Picasso portrait and a Duccio madonna, and that his daughter, with her "spindly legs and big bum", is like Tenniel's drawing of Alice. "

- ↑ The Sea, p. 9

- ↑ cf. Die See, p. 65: “... back then I was always on the hunt for opportunities to see naked meat. What stimulated my imagination were of course the erotic explorations of these heavenly beings. "

- ↑ Thomas David, The Tides of Remembrance, John Banville shows himself in “Die See” at the height of his art, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, September 5, 2006: “The gods of Olympus once made the strictly Christian-raised murders the“ sin of Looking back "seduced: In retrospect of his story, he remembers the hardly childlike passion with which, as an eleven-year-old, he pursued" the erotic explorations of these heavenly beings "in books and art magazines, whose inapproachable glory he saw in that distant summer with the fascinating Grace family then seemed to appear in person. "

- ↑ The Sea, p. 104

- ↑ The Sea, p. 78

- ↑ cf. The Sea, p. 99f.

- ↑ cf. the references in the review by David Grylls: "Fiction: The Sea by John Banville", The Sunday Times of June 12, 2005: "Mr Grace is an" old grinning goat god ", a satyr (but also, confusingly," the Poseidon of our summer ”). Mrs Grace is a daemon, an avatar, a maenad. The twin children are also recruited for mythology. Myles, who is mute and has webbed toes (“the marks of a godling”), is a “malignant sprite”. Chloe, producing "an archaic pipe-note" by blowing on a blade of grass, is Pan. Even the children's governess, Rose, is "Ariadne on the Naxos shore". "

- ↑ Die See, p. 82ff

- ^ John Banville, The Sea, p. 197

- ↑ cf. Die See, p. 15: "... the uncanny is by no means something new, but rather something well-known that only returns to us in a different form, that becomes a revenant"

- ↑ Die See, pp. 20f.

- ↑ The Sea, p. 22

- ↑ cf. The Sea, p. 176

- ↑ The Sea, p. 21

- ↑ "At which point, please go back and read that short paragraph about Mr. Todd and tell me whether I'm crazy or not. The Toddery seems to me terribly miscalculated, a shot at humor or wordplay that has scant chance of being the glove to enclose the cold hand (Mr. Banville is extraordinary on coldness) of death. "; David Thomson, Heavy With Grief and Mourning, Thick With Eccentric Verbiage, The New York Observer, November 13, 2005

- ↑ John Crowley, Art and Ardor, Washington Post, November 13, 2005

- ↑ cf. the references in David Grylls' review, "Fiction: The Sea by John Banville," The Sunday Times, June 12, 2005

- ↑ cf. for example the review by Yvonne Zip: "Irish writer John Banville has a reputation as a brilliant stylist - people like to use the word" Nabokovian "in reference to his precisely worded books. His 14th novel, The Sea, which won the Man Booker Prize last month, has so many beautifully constructed sentences that every few pages something cries out to be underlined. ", The Christian Science Monitor, November 6, 2005

- ↑ for example David Thomson, Heavy With Grief and Mourning, Thick With Eccentric Verbiage, 2005: “He's a mystery: Sensitive to a fault to the memories of hurt and the passions of childish cruelty, he also sprinkles his book with eccentric verbiage: levitant , cracaleured, horrent, cinereal, glair, torsion, caducous, velutinous, bosky and so on. It's not just that this learning isn't shared by the other characters in the story; far more deadly, it's an ostentation that takes away from the emotion in Mr. Banville's best writing. "

- ↑ Tibor Fischer, Wave after wave of vocabulary, Telegraph July 6, 2005: “As the novel progressed I realized that it was more like sitting an exam than taking in a tale: Banville's text is one that constantly demands admiration and analysis. Bard of Hartford? Nom d'appareil? Cracaleured? If the preciosity was used solely for comic effect it would work better, but I suspect Banville is after some elegiac granite here. "

- ↑ “What sort of signal is this for a novel that's heavy with real grief and mourning, in which the sea, ultimately, is the undeniable natural force that will claim us all, just as — in life — it sometimes patiently allows itself to be a panorama of peace or beauty or calm? ”, David Thomson, Heavy With Grief and Mourning, Thick With Eccentric Verbiage, The New York Observer, November 13, 2005

- ↑ The Sea, p. 91

- ↑ "He was a scoundrel, probably even a dangerous, and through and through a cheerfully immoral person", Die See, p. 88

- ↑ The Sea, p. 80

- ↑ litencyc.com : "Twins: the Gods, godlings, strikingly alike, watching the narrator across the edge of the water. Gods or devils? Heavenly twins who "laugh like demons". Who is watching whom? I am seen therefore I am. "

- ↑ Claudia Kuhland, Erinnerte Liebe: The masterful novel "Die See" by Booker Prize winner John Banville, WDR review from October 2, 2005

- ↑ The Sea, p. 107

- ↑ The Sea, p. 108

- ^ The Spiegel review online

- ↑ The Sea is a book, I fear, that won't do the Man Booker's reputation much good. Of course, the Man Booker prize shouldn't be allotted to a work on the basis of its probable readership, it should be awarded on quality, but nevertheless the Booker winner is one of the few titles that readers will pick up this year. I reviewed The Sea three months ago, and I'm afraid I can't remember anything about it, apart from the fact that it was set by the sea and that I was impressed by the vocabulary. It's a nebulous, oversubtle choice for the folks in Hampstead, rather than the general reader.