Eckert I and Eckert II projection

The Eckert I projection and the Eckert II projection are two trapezoidal pseudo-cylindrical map projections with a hexagonal shape published by Max Eckert-Greifendorff in 1906 . They are a cartographic study, but they were already used for maps by Abraham Ortelius around 1570.

properties

All Eckert projections are map network designs with parallel latitudes of unequal length , with the poles being shown in the form of a polar line that is half as long as the equator . The central meridian is also 1: 2 to the equator. The projection thus creates a well-proportioned format of the world map with an appealing overall picture and good orientation at the same time. The pole problem of the rectangular maps (the pole regions are either excessively wide or are becoming increasingly illegible) is solved by the design with the harmoniously dimensioned pole line.

With these two variants, the longitudes are straight lines that (except for the central meridian) have a kink at the equator.

The Eckert-I variant is neither true-angle (conformal) nor true-area , but has equidistant circles of latitude. As with the flat map , the graticule is thus completely straight, stretched centrally in a north-south direction . Eckert-II is the equal-area version. In the first draft the scale is correct in the areas 47 ° 10 ′ N and S , in the second in the areas 55 ° 10 ′ N and S. No point on the map is free of distortion; there are particular irregularities at the equator.

calculation

The Eckert I projection is in principle a rectangular flat map that is compressed by a factor of 2 towards the poles . For the Eckert II projection, the widths are modified for equal area and the lengths are adjusted.

If the radius of a sphere (whose surface serves as a model for the earth's surface), the central meridian and a point with the polar coordinates are given, the coordinates and the image point on the map can be calculated using the following formulas:

Eckert-I:

- ,

- ;

Eckert-II:

- ,

- .

Use and advancements

The trapezoidal projection has been known since ancient times, it is attributed to Hipparchus who used it in star maps , and was then used by Donnus Germanus for illustrations of the works of Ptolemy.

Both designs serve as a theoretical didactic approach at Eckert and demonstrate a completely linear map network for a world map .

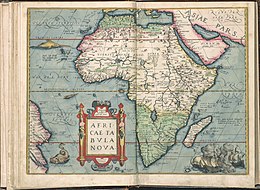

In fact, the Eckert I projection was already used by Ortelius for his atlas Theatrum Orbis Terrarum , first printed in Antwerp in 1570, for the map Africa tabula Nova (No. 6)

In practice, the two designs are no longer used today (curiosity card).

Similar designs

Eckert's other designs are based on this approach, they are then no longer acute-angled at the equator, Eckert-III and Eckert-IV are elliptical, Eckert-V and Eckert-VI sinusoid, each in the equally spaced and equal-area variants.

The Eckert-II is similar in principle to the also equal-area Collignon projection , which, however, only represents one hemisphere in a triangular shape.

See also

- Eckert projection (overview)

literature

- Max Eckert: New designs for earth maps. In: Petermanns Mitteilungen , Vol. 52 (1906), No. 5, pp. 97-109, ISSN 0031-6229

- Max Eckert: The map science. Research and fundamentals on cartography as a science . VWV, Berlin 1921/25 (2 vol.) 1921.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Rolf Böhm: Map projections - pseudocylindrical projections : Eckerts Erdkarteennetze , boehmwanderkarten.de (with images)

- ↑ Carlos Alberto Furuti: Flat-Polar Pseudocylindrical Projections: Six Projections by Eckert , progonos.com → Map Projection (accessed February 15, 2015).

- ^ A b John P. Snyder: Map Projections - A Working Manual . USGS Professional Paper 1395. Denver 1987, ISBN 0-226-76747-7 , pp. 253–258 ( web link to pdf , usgs.gov [accessed July 24, 2013] with a more detailed history section).

- ↑ a b c d e f John P. Snyder: An Album of Map Projections . USGS Professional Paper 1453. Denver 1989, ISBN 0-226-76747-7 , pp. 86 f. and 88 f . ( Web link to pdf , usgs.gov [accessed on February 11, 2015] Formulas p. 223, col. 2, 70–74).

- ↑ John P. Snyder: Flattening the Earth: Two Thousand Years of Map Projections . University of Chicago Press, 1997, ISBN 0-226-76747-7 , pp. 191 .

- ↑ a b Gerald I. Evenden: Cartographic Projection Procedures for the UNIX Environment - A User's Manual , p. 23 ( pdf ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link accordingly Instructions and then remove this note. , There p. 27; on remotesensing.org, ftp; with illustrations).

- ↑ a b c Eckert I , Eckert II , arcgis.com.

- ↑ CA Furuti: premodern Projections: Equidistant Cylindrical and Maps , progonos.com.

- ↑ Ortelius uses rectangular or trapezoidal projections for small and large-scale maps (so up to Romanii Imperio Imago , 65); That he was also familiar with other concepts is shown by the Asia (5) and the Typus orbis Terrarum (1), a variation of an Appian projection called Ortelius oval projection , which is similar to an Eckert III projection ; The fact that Africa is shown in Eckert-I may be due to the fact that the equatorial jump was a familiar procedure in navigation at the time; in fact, only maps with coastlines show a graticule in the entire atlas; whether the India Orientalis (86) is an Eckert-I remains unclear because of the missing graticule.