A shabby sex

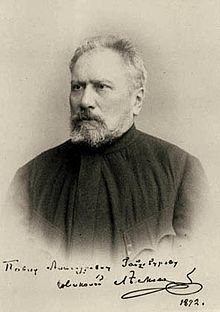

A rundown sex , even the dying Gender ( Russian Захудалый род , Sachudaly rod ), is a novel by Russian writer Nikolai Leskov , who was born in 1873 and 1874 in July, August and October issue in Katkov's literary journal The Russian Messenger was published.

In the present chronicle, the princess' daughter WDP tells about her ancestors, the Protosanovs. These had already owned their own principality before the reign of Kalita , but were later executed, flogged and exiled. So they got the nickname the "decrepit" under Alexei I , but strived up again under his daughter Sofija . Actually, the narrator is interested in much more than a family story. The text is harsh criticism of the Russian hereditary landed gentry, who inevitably deteriorated over time and who thought before 1861 that a landlord had little to understand about economics .

The Princess Varvara Nikanorovna

The novel deals with the struggle for survival and the downfall of the widowed Princess Varvara Nikanorovna Protosanova from Dranka, the owner of the village of Protosanowo in the Oryol governorate . Princess Varwara, the richest woman in the governorate, is the grandmother of the narrator.

Prince Lev Lwowitsch Protosanow fell in love with the 14-year-old Varvara, who came from a poor family, and was very attractive. After the wedding, the couple had two children - the older Anastassija and the younger Jakow. The empress had given the prince land and he had grown rich over time. But the ruler's affection had its price. Anastasija had to be brought up in a Petersburg aristocratic monastery - fifteen hundred versts from Varvara . Fortune finally left the Protosanovs entirely. Regimental commander Prince Lev fell out of favor at court after he had repeatedly unsuccessfully taken to the field against the oncoming French after Napoleon's attack . So the desperate prince sought and found death in an open attack on the enemy. Princess Varwara had given birth to her son Dmitri, the father of the narrator, shortly after the death of Prince Lev. At that time, shortly after 1812, the novel begins.

The princess only felt at home in her country estate, far from the Petersburg court. Leskow writes about Varvara: "Her villages became rich and prosperous: Her serfs bought land elsewhere on the princess's name and trusted her more than themselves."

When the now 17-year-old Anastassija ended her retirement, Princess Varvara had to look after her daughter in Petersburg for better or worse. In the residence, the princess could not avoid a visit to the unloved relative Countess Antonida Petrovna Chotetowa. There, in the salon, the now 35-year-old countess got to know and appreciate the Baltic Count Vasily Alexandrowitsch Funkendorf, who is around 50 years old in Petersburg . The count, a man of Lutheran faith, had received land from the crown adjacent to the land of the princess in Protosanowo. Funkendorf wants to own the land of the princess. Warwara's frank, simple character encourages Funkendorf to propose marriage. The widow with three children rejects him and from then on demonstratively wears the old woman's hood.

Princess Varwara returns to the province with her daughter. Anastassija wants to escape the boring country life, no matter what the cost. To the horror of the mother, the young girl accepts the proposal of the much older Count Funkendorf. The Lord has achieved his goal with the marriage of convenience that Chotetova had arranged on his behalf. The princess bequeaths more land to her daughter than Funkendorf had hoped for. Varvara soon regrets her generosity. Funkendorf wants to relocate property owners among their former farmers.

When Varvara is instructed to take her two sons to a St. Petersburg educational institution, she does not reply. Melancholy , she neglects contacts with acquaintances in the future and is eventually forgotten. Varvara bequeaths the rest of the property to the two sons in due course, retires to old age, eats the bread of grace at her friend Marja Nikolaevna's and dies impoverished.

Princess Warwara's friends

- Olga Fedotovna was eight years younger than Varvara. The servant child from Protosanowo began his apprenticeship as a milliner as a little girl in Moscow and later became Warwara's maid. Olga was popular in Protosanowo because she never denounced anyone with the princess.

- Patrikej Semjonowitsch Sudaritschew was about 20 years older than Varvara. The rather thorough, concentrated thinker, a solid character, fanatically adhered to the old order and was slavishly devoted to the princess. Patrikej had to bring the news of Prince Lew's death to Varvara.

- Petro Graiworona, the trumpeter, had seen Prince Lev fall.

- Don Quixote, actually the noble Dorimedont Wassiljewitsch Rogoshin, appears to be a little crazy. Next to the Princess von Leskow, this figure was worked out in the most memorable narrative way. Rogoshin tirelessly stands up for the serfs throughout the entire novel and thus makes bitter enemies among the crowd of officials. Law enforcement agencies persist in pursuing the fearless nobleman. He always has to hide. Rogoshin tries to punish the intriguer Chotetowa and the dowry hunter Funkendorf.

- Marja Nikolajewna, the daughter of the deacon Nikolai who was blinded by lightning, marries a much younger blond seminarist out of reason. With her husband, the deacon's successor, Marja ensures the survival of her family.

- Mefodi Mironytsch Tscherwjow is not a friend of the princess. But Varvara feels drawn to him. The historian Professor Chervyov taught history, had proved unsuitable, was replaced, taught philosophy, left university voluntarily and teaches children to read and write in Kursk . Varvara wants Chervyov to teach her two boys, but after a long dispute with the professor refrains from doing so. Chervev is exiled to the Belyje Berega monastery anyway . There, shortly before his death, he answered a question from Countess Chotetova, who was passing through. Leskov does not give the question, but does give the answer. This reads: "Do what you think is right, you will definitely regret it."

reception

- 1959: Setschkareff thinks that Leskov's exaggerations are detrimental to the effect of his text. As examples he cites the blatant drawing of the hypocrite Funkendorf and the bigoted Chotetowa.

- 1970: In the section The Duration of Time, Zelinsky points to a consequence of the narrator's narrative attitude. Because she only mentions what she still knows, there are gaps in memory in the plot. Only a narrator could smooth the periods.

- 1975: Reissner writes about the figure of Chervev: "Inevitably, his ethical ideas and his idealistic anarchism, influenced by Tolstoy's teachings, remain utopian at such a time."

literature

German-language editions

Output used:

- A shabby sex. Family chronicle of the princes Protosanov. Translated from the Russian by Günter Dalitz. P. 507–766 in Eberhard Reissner (Ed.): Nikolai Leskow: Collected works in individual volumes. The clergy. 807 pages. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1975 (1st edition)

Secondary literature

- Vsevolod Sechkareff : NS Leskov. His life and his work. 170 pages. Verlag Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1959

- The dying sex. P. 250–291 in Bodo Zelinsky : Roman and Romanchronik. Structural studies on Nikolaj Leskov's storytelling. 310 pages. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 1970

Web links

- The text

- Entry in the Laboratory of Fantastics (Russian)

- Entry in WorldCat

annotation

- ↑ Leskow hides the year the plot ends. On the way, he only sets sparse, easily recognizable time stamps. For example, in the 21st of the 37 chapters of the novel, the uprising in Chuguevo is mentioned . That was in 1819 (Russian Chugujewo ). One thing is certain: the plot runs for a number of years. Leskov writes: "For the wide-ranging plans of the Populists . Had they [the Princess Varvara] not much left" (used edition, p 658, 2nd ACR) As the Populists were active in 1860, the novel's action would then run on a tight half a century. That corresponds very poorly to the long narrative distance that the first-person narrator sometimes reveals. A duration of a quarter of a century would be more appropriate.