Treaty of Fürstenwalde

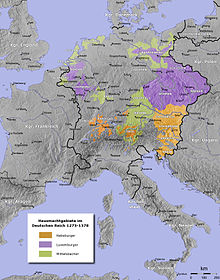

The Treaty of Fürstenwalde of August 18, 1373 was a treaty dictated by Emperor Charles IV , in which the previous Elector of Brandenburg , Otto V , "the lazy", for a compensation of 500,000 guilders and some castles and towns in the Upper Palatinate renounced the power of rule over the Margraviate of Brandenburg in favor of the Luxembourgers . This ended the approximately 50-year rule of the Wittelsbachers in Brandenburg.

Background and consequences

Emperor Charles IV had been working systematically for a long time to acquire the mark. The young, politically inexperienced Otto turned out to be hardly an equal opponent, but initially did little to preserve the electorate for the Wittelsbachers. A Wittelsbach-Luxemburg inheritance contract had existed since 1363, which guaranteed the Luxembourgers the inheritance of the Electorate of Brandenburg if its Wittelsbach rulers remained childless. When Otto's older brother, Ludwig the Roman , died in 1365 and Otto was given sole control of the Mark Brandenburg, he was just 21 years old. In October of the same year Otto Karl IV transferred the administration of Brandenburg for six years, whereupon Karl sent a number of foreign councilors and court officials to the Spree. In 1366, Karl Otto was also related to himself by marrying him to his daughter Katharina von Luxemburg . As a result, Otto stayed increasingly at the Prague court and hardly cared about the government of the Mark Brandenburg. In 1367 Charles IV received Niederlausitz as a pledge, which was a clear step towards acquiring Brandenburg as well. In 1368 Otto removed the alien councils during the emperor's second march to Italy 1368-69 and found support among the Brandenburg nobility. At the end of the six years, Charles IV moved into the Mark with an army to demonstrate his claim to power. After a military conflict with Otto and a subsequent armistice of 1371, he appeared again at the head of his troops in 1373 in the Mark, and now Otto was forced to renounce the Mark entirely. However, since Otto had allied himself with his relatives, the war-experienced Bavarian dukes, he was able to enforce the high compensation of land and money, as well as the electoral vote and the office of treasurer until his death. Otto was even able to keep the title of "Margrave of Brandenburg".

Otto then moved to Bavaria to Wolfstein Castle on the Isar near Landshut , where he had a love affair with a miller while his wife stayed in Prague. Karl had meanwhile reached his goal. With Brandenburg he also had another electoral vote, which he needed to secure his successor in the empire at the next election. In 1376, as stipulated in the contract, the Brandenburg electoral vote in the election of Karl's son Wenzel was still held by Otto. Brandenburg was also important in order to control the trade routes leading from its Bohemian and Silesian possessions towards the Baltic and North Sea. In return , Karl gave up his project to expand Bohemia to the west , his previously acquired northern Gauze possessions in the Upper Palatinate went to Otto. Karl therefore also made sure that his new acquisition was managed efficiently. he had Tangermünde expanded and the ownership structure in the Mark recorded in writing in the land register of 1375 . The Mark Brandenburg remained in the hands of the Luxembourgers until 1415/17, who then gave it to the Frankish branch of the Hohenzollern under Sigismund I.

Subsidiary contracts and declarations

There were some side declarations or contracts to the leasing and compensation agreement. The Codex diplomaticus Brandenburgensis, for example, contains a prescription from Charles IV entitled as follows by Riedel , issued on August 17, 1373: Emperor Karl prescribes to Margrave Otto that he should retain the cure and the office of treasurer of the ceded Mark Brandenburg for life and that the emperor's sons may not bear the title of elector. It says, among other things:

“W y r K a r l, by the grace of God R o m i ſ c h e r K e y ſ e r, at all times Merer des Reich and Kunig in Beheim, can obviously confess and do with this letter […]. […] So that while he is alive, he is an elector and master of the holy empire ſ a ulle, hindered by us, our children and heirs, and in good faith […] and that I am not an elector of children or heirs or Ertz Cammerer from the Brandenburg brand because of writing, [...]. "

In a declaration of August 18, 1373 Otto's nephew Friedrich von Bayern , whom Otto had designated as his successor, also waived all claims to the mark. He also waived on behalf of his father Stephan II and his brothers. Riedel wrote a certificate from Otto dated August 28, 1373: Margrave Otto referred all residents of the Mark Brandenburg to the Emperor and his son Wenzel and gave this Hasse von Wedel von Uchtenhagen as a guide.

Documents and literature

Certificates

Adolph Friedrich Riedel has put together some documents and declarations about Otto V's resignation in the Codex diplomaticus Brandenburgensis . Since the entire Codex is available in digitized form, these documents and sources can be viewed on the Internet:

literature

- Richard George: Margrave Otto the Lazy , in: Hie gut Brandenburg all way! Historical and cultural images from the past of the Mark and from old Berlin up to the death of the Great Elector. Edited by Richard George, Verlag von W. Pauli's Nachf., Berlin 1900, pp. 182-188.

- Jörg K. Hoensch : The Luxembourgers. A late medieval dynasty of pan-European importance 1308–1437 , Stuttgart 2000.

- Emil Theuner: Otto with the later nickname of the lazy . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 24, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1887, pp. 663-669.

Individual evidence

- ^ Jan Winkelmann: The Mark Brandenburg of the 14th Century, 2011, ISBN 978-3-86732-112-9 , p. 81.

- ↑ a b Jörg K. Hoensch, p. 155f.

- ↑ a b Emil Theuner, ADB

- ↑ Codex diplomaticus Brandenburgensis, Second Main Part, Volume III, p. 8.

- ↑ Certificate in Codex diplomaticus Brandenburgensis, p. 8f.

- ↑ Certificate in Codex diplomaticus Brandenburgensis, p. 15f.