Faubourg Saint-Marcel

The Faubourg Saint-Marceau or Saint-Marcel is a Parisian district on the border of the 5th to the 13th arrondissement .

history

In ancient times , the area was not inhabited. At the beginning of the 4th century there was an extensive necropolis here , which stretched along the Roman road to Melun : the ashes of the deceased kept in the hypogeum left traces in the etymology of the quarter: today's rue Broca was formerly called rue de Lourcine Terre de lococinerum (place of ashes), which became the Clos de la Cendrée (Cendres = ashes) under King Louis VII . The southern part of the Faubourg Saint-Marcel retained its role as Terre des morts (place of the dead) until the time of the Merovingians .

Presumably Bishop Dionysius of Paris consecrated a simple chapel here to Saint Clement in the 3rd century . After Bishop Marcellus of Paris was buried here in 436 and a cult of saints had developed around him, the prayer chapel of St. Marcel was built over his grave in the 5th century or the beginning of the 6th century. The place that developed around this chapel, originally called Chambois or Chamboy , soon took on the name of its patron. In 884, in connection with the raids by the Normans, the relics of Marcellus were brought to safety in the cathedral on the Île de la Cité - a correct decision, since the place was destroyed by the raids and was not re-established until the 10th century.

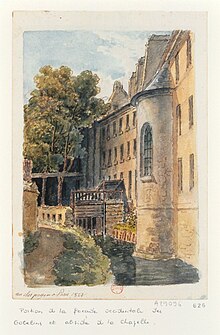

The construction of the collegiate church of Saint-Marcel in the 11th century, the chapel of Saint-Martin, the church of Saint-Hippolyte and the establishment of the parish of Saint-Médard (1183) on the left bank of the Bièvre in the area of Saint-Marcels and under the jurisdiction of the Sainte-Geneviève Abbey gave the place a new face. At the beginning of the 13th century, the place was surrounded by a wall and a ditch in front, both of which were torn down or filled in between 1557 and 1561.

The location outside Paris attracted a number of nobles from the end of the 13th century, starting with Marguerite de Provence († 1295), the widow of Louis the Saint , who founded the Couvent des Cordeliéres in the west of the village in 1289 , and who in Had a residence built nearby where she lived with her daughter Blanche († 1320), the widow Ferdinand de la Cerdas († 1275) (the Hôtel de la Reine Blanche, which does not mean the daughter, but the mother , who was known as the Queen Dowager as Reine Blanche ; the Bal des Ardents may have taken place here in 1393 ). She was followed by the Count of Boulogne , the Count of Forez , the Bishop of Laon Roger d'Armagnac, and Miles de Dormans, the Chancellor of France , who ceded his house to the Duke of Orléans (the Séjour d'Orléans east of the Church of Saint- Médard on the banks of the Bièvre). The Couvent des Cordelières took Isabella of Valois, sister of King Philip VI in the 14th century . and widow of Duke Peter I of Bourbon (X 1356) who died here in 1383. Catherine de France (1378-1388), the youngest sister of King Charles VI. , was brought up here after the death of her mother Jeanne de Bourbon in 1378. From the 15th century, Saint-Marcel came out of the murders and the aristocratic palaces gave way to handicraft businesses.

The part of Saint-Marcel, which lay on the right bank of the Bièvre, was subordinate to the canons of Saint-Marcel, who in 1238 released their serfs to freedom. Later King Philip IV elevated the village to a city. In 1296, the Parlement of Paris guaranteed the town's fiscal independence, which led a number of trades to settle here, including the first butchers who use the Bièvre to get rid of their rubbish, which is why one of the bridges over the creek is Name "Pont aux Tripes" (bridge of the bowels) was called. This was followed by the tanner , the tanner , the dresser, the shoemakers and dyers who made jointly from the Bièvre the extremely polluted water, which it remained until the second half of the 20th century. Numerous hostels and restaurants sprung up along the Bièvre, frequented by Rabelais and Jean-Jacques Rousseau .

In 1443 Jean Gobelin settled in Saint-Marcel and founded his dye works, which later became the Gobelin manufacture , with which he and his descendants made a large fortune up to the 16th century; the southern part of the village still bears the family's name today. In 1662, Louis XIV settled the craftsmen in Saint-Marcel who had worked on behalf of Nicolas Fouquet at Vaux-le-Vicomte Castle until his fall . In 1663 the Gobelin manufacture became the Manufacture royale des meubles et tapisseries de la Couronne under Charles Lebrun , for which a large number of new buildings were erected, partly in the direction of Rue Mouffetard (today Avenue des Gobelins ), partly on the bank the Bièvre, and which Louis XIV generously supported at the beginning of his sole rule. Tapestries, silver dishes, chandeliers and furniture were produced here for the court. When Louis XIV finally swapped the Louvre for the Palace of Versailles , the manufactory began to decline, even if it continued to produce well-known handicrafts.

The prosperity generated by the manufactory should not hide the fact that only the specialists working here benefited from it. The majority of the population lived in poverty and the neighborhood had a bad reputation well into the 19th century, as reported by Rousseau in his Confessions , published in 1782 .

The French Revolution fell on fertile ground here, of course, from the Faubourg come spokesmen such as Louis Legendre (1752–1797) and Antoine Joseph Santerre (1752–1809).

In the 19th century, the Faubourg Saint-Marcel was integrated into the city of Paris. The Industrial Revolution led to a large influx of penniless workers, which continued to plunge the neighborhood into misery. With the urban planning work of Baron Haussmann, Saint-Marcel's face changed. In 1857 it was decided to build Boulevard Saint-Marcel and Boulevard Arago. Within two years, the bulk of the old structure disappeared. During the construction work, the immense Christian necropolis from late antiquity was discovered, some of which is still under the surface today. Also in the 19th century began work on the capping of the Bièvre, some of which was not completed until the eve of the Second World War; Today the city of Paris is in the process of at least partially reversing this cap.

The Faubourg Saint-Marcel is now one of the most expensive residential areas in the 13th arrondissement.

Attractions

- Gobelin Manufactory (entrance at 42 Avenue des Gobelins)

- The Hôtel de la Reine Blanche (Rue des Gobelins 17, possibly the location of the Bal des Ardents , the current building comes from the Gobelin family)

- The Saint-Médard church ( Rue Mouffetard )

- The Saint-Marcel church (built in 1966, the old Saint-Marcel collegiate church was destroyed in 1806)

- The former Théâtre des Gobelins (73 avenue des Gobelins)

- The Hôtel Scipion (Rue Scipion 13), built in 1565 for the Italian financier Scipio Sardini

- The René-Le-Gall square between the Hôpital Broca and the Manufacture des Gobelins. The area was never built on; it was owned as a green space by the Cordelières and the Gobelin and Le Peultre families; the present park was laid out in 1936 by Jean-Charles Moreux.

- The Hôpital Broca

literature

- Bernard Rouleau: Paris. Histoire d'un espace . Seuil, Paris 1997.

- Alfred Fierro, Jean-Yves Sarazin: Le Paris des Lumières d'après le plan de Turgot (1734–1739) . Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris 2005.

- Théophile Lavallée: Histoire de Paris. Depuis le temps des Gaulois jusqu'à nos jours . Paris 1857.

- Jean-Jacques Lévêque: Vie et histoire du XIIIe arrondissement . Hervas, Paris 1995.

Web links

Footnotes

- ^ "Combien l'abord de Paris démentit l'idée que j'en avais! La décoration extérieure que j'avais vue à Turin, la beauté des rues, la symétrie et l'alignement des maisons me faisait chercher à Paris autre chose encore. Je m'étais figuré une ville aussi belle que grande, de l'aspect plus imposing, où l'on ne voyait que de superbes rues, des palais de marbre et d'or. En entrant par le faubourg Saint-Marceau je ne vis que de petites rues sales et puantes, de vilaines maisons noires, l'air de malpropreté, de la pauvreté, des mendiants, des charretiers, des ravaudeuses, des crieuses de tisane et de vieux chapeaux. Tout cela me frappa dtabord à un tel point que tout ce que j'ai vu depuis à Paris de magnificence réelle n'a pu détruire cette première impression, et qu'il m'en est resté toujours un secret dégoût pour l'habitation de cette capitale. "