Frog mouse war

The frog mouse war ( ancient Greek Βατραχομυομαχία Batrachomyomachía , originally called Batrachomachia for short, "frog war") is an epyllion from the late Hellenistic period that has been handed down under the name of Homer and depicts a war between the frogs and the mice as a parody of the Homeric epics .

Authorship and dating

As the (mostly legendary) ancient homebiographies report, Homer is said to have written the frog mouse war as well as the lost epicichlids and other fun poems when he was a schoolmaster on Chios and had to entertain the children. Today, this tradition is just as absurd as an attribution to a certain Pigres of Halicarnassus from the early 5th century BC that goes back to Plutarch's writing The Malice of Herodotus . BC, who probably never existed or was not a poet. On the basis of lexical and stylistic features, the text is rather dated to the late Hellenistic period. Ahlborn suggests that it was written in or around Alexandria in the 1st century BC. To consider especially probable. The first reliable mention of the frog mouse war and thus a terminus ante quem can be found in Martial ( Epigrammata XIV 183) around 85 AD, and similarly in Statius ( Silvae I praef.).

A relief by the sculptor Archelaos of Priene (between 3rd century BC and 1st century AD), which is now in the British Museum in London and depicts Homer 's apotheosis , has long been used as an argument in favor of an earlier date . At the foot of the throne on which Homer sits there, two roughly carved animal figures can be seen in which one believed to see a frog and a mouse in the 19th century, which means that Archelaus would have ascribed the Batrachomyomachia Homer. However, it is not only the lifetime of Archelaus itself that is uncertain, the two animals are also difficult to recognize and could just as easily be a later addition or (as was assumed until the 19th century) represent two mice, which would then ironically represent strict literary critics , Homer's poems "gnawed".

content

The poem is about 300 hexameters ; the number fluctuates depending on how many verses you think are interpolated .

The Proömium (verses 1–8) heralds the report of a gigantic war in epic tradition and language, after which the insignificant content seems all the more funny. Based on the Aesopian fable of frogs and mice (No. 302 Hausrath), it tells how the prince mouse Krumendieb (Greek Psicharpax: all names are "speaking") quenched his thirst at a pond when the frog king Pausback (Physignathos) appeared and asks him about origin and gender (13-23). The mutual imagination, which is exactly copied from the encounters of Homer's heroes, ends in the self-praise of crooks for the culture of the mice, which is superior to that of the frogs (24–55).

In response, Pausback invites him to visit his empire: He wants to carry him across the pond on his own back, which the two of them begin (56–81). Suddenly, however, a water snake appears, which is why Pausback literally disappears and the poor crook, miserable but swearing vengeance, drowns (82–99). The whole event is followed from the bank by the mouse tafellecker (Leichopinax), who reports the misfortune to the mice, who are seized with great anger, especially Krumendieb's father, the king bread rodent (Troxartes; 100-107).

In the people's assembly, the mice decide to take revenge under bread nager's leadership against the frogs and prepare for it (108-131). The Frog King Pausback meanwhile denies any guilt, so that the frogs in the council also decide on armament (132–167). As befits Homeric tradition, a parallel assembly of gods now follows: Zeus pathetically urges the gods to help one of the two sides, while Athena, on the other hand, is tormented by unexpected earthly worries caused by both animal species (mice in the temple, money worries and headache from the croaking of the frogs), pleads for only following the battle neutrally (168–201). The gods agree to Zeus so that he opens war.

This is followed by an extensive description of the battle (202–259), which, as in Homer v. a. consists of duels between individual heroes and verbosely lists wounds and types of death. Overall, however, the description is so confused that research has already assumed an originally independent development of this part of the text, which would then have been inserted into the Epyllion only later.

After much back and forth the battle seems to be decided by the “high performance” ( Aristie ) of the mouse Bröckchenräuber (Meridarpax), who threatens “to wipe out the sex of the frogs” and drives their front to flee (260–269). Zeus now takes pity on the frogs, whose complete annihilation he foresees, and calls on the gods to intervene, but of all things the god of war Ares points out that the strength of individual gods is insufficient to stop this battle (270-284). At Ares' suggestion, Zeus hurled his terrible thunderbolt, but although "the whole of Olympus trembled," the mice were not stopped (285–292). Zeus finally sends an army of armored crabs or crabs to help, who manage to chase the mice away (293–303). "The sun was already setting, and the whole day-long war magic was over."

Effect and re-seals

The frog mouse war became school reading very early on, as evidenced by the large number of over 100 surviving manuscripts as well as scholia and commentaries ( e.g. by Moschopulos ) as well as the extensive processing of the text. The latter has led to numerous interpolations (inserted verses and entire sections), often quotations from Homer, with which eager readers tried to make the parody even more parodistic, as well as to two strongly differing reviews from the Byzantine period including mixed versions. The oldest surviving manuscript is Codex Baroccianus 50 from the 10th century, the Frog Mouse War was printed in Brescia as early as 1474 and is thus one of the first books to be printed in Greek, and perhaps even the oldest.

The classical philology of the 19th century did much to secure the text and its attribution, crowned by the monumental critical edition of Arthur Ludwich (1896). However, it also began with a disparaging treatment of the "fake" poem, which is still referred to in the critical Homer edition of Th. W. Allens (Oxford 1912 and other) as miserum poema , "miserable poem". This blanket condemnation, which has now become rare again, is offset by the enormous literary aftermath of the frog mouse war .

The most famous adaptations include the Froschmeuseler by Georg Rollenhagen (1595), who expanded the poem into a somewhat rambling epic of 10,000 verses, the Latin adaptation by Jacob Balde (1637) in five books and v. a. the Italian adaptation and continuation in the Paralipomeni alla Batracomiomachia by Giacomo Leopardi (1831–1837). Leopardi translated the poem three times in the course of his life, he was so enthusiastic about it; Iacopo Vittorelli had previously translated the epic into Italian. Chapman and later Alexander Pope (London 1721) made other important poetic transmissions .

The Batrachomyomachia also inspired completely new works : Inspired by the frog mouse war , the Byzantine poet Theodoros Prodromos created the cat mouse war in the first half of the 12th century , a reading drama as a parody of the ancient tragedy. The baroque poet Lope de Vega imitated the epic in a cat war (1618). The most important testimony to the reception, however, is undoubtedly the aforementioned “continuation” from Leopardi's pen.

The frog mouse war inspired the Austrian composer Herbert Willi to write an orchestral work (premiered in 1989, Wiener Symphoniker with Barbara Sukowa under Claudio Abbado as part of the Wien Modern festival ).

Text output

- Arthur Ludwich (Ed.): The Homeric Batrachomachia [!] Of Karers Pigres with scholia and paraphrase. 1896.

- Thomas William Allen (Ed.): Batrachomyomachia. In: Homeri opera. Volume 5. Oxford 1912 a. ö. (OCT).

- Reinhold F. Glei (ed.): The Batrachomyomachia. Synoptic edition and commentary (= studies on classical philology. Volume 12). Lang, Frankfurt am Main / New York / Nancy 1984, ISBN 3-8204-5206-0 .

Translations

- The frog and mouse war, a joking hero poem. Translated from Greek into prose by Theophilus Coelestinus Piper . Struck, Stralsund 1775. ( digitized in the digital library Mecklenburg-Vorpommern)

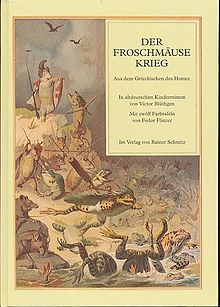

- The frog mouse war . German translation (in four-part iambs) by Victor Blüthgen , illustrated by Fedor Flinzer . Frankfurt am Main 1878

- The frog and mouse war (Batrachomyomachia). Greek / German, translated by Thassilo von Scheffer . Heimeran, Munich 1941 (Tusculum).

- Pseudo-Homer: The Frog Mouse War. Theodoros Prodromos: The cat-mouse war. Greek / German by Helmut Ahlborn. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin (East) 1968. 4th, revised edition 1988 (SQAW 22).

- Fabian Zogg (Hrsg./Übers.): Froschmäusekrieg , in: Greek Kleinepik, Hrsg. Manuel Baumbach, Horst Sitta, Fabian Zogg, Tusculum Collection , 2019 (Greek-German)

literature

- Helmut Ahlborn: Investigations on the pseudo-Homeric Batrachomyomachia. Dissertation University of Göttingen 1959.

- Otto Crusius : Pigres and the Batrachomyomachia in Plutarch . In: Philologus 58 (1899) pp. 577-593.

- Massimo Fusillo: La battaglia delle rane e dei topi. 1988.

- Reinhold F. Glei: Article Batrachomyomachia. In: The New Pauly . Volume 2. 1997, column 495f.

- J. van Her Werden: The Batrachomyomachia. In: Mnemosyne. New series 10 (1872) pp. 163–174.

- Glenn W. Most : The Batrachomyomachia as a serious parody. In: Wolfram Ax , Reinhold F. Glei (ed.): Literature parody in antiquity and the Middle Ages. Wissenschaftsverlag Trier, Trier 1993, ISBN 3-88476-046-7 , pp. 27-40.

- Jacob Wackernagel : Linguistic research on Homer. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1916, pp. 188–199.

- Hansjörg Wölke: Investigations on Batrachomyomachia (= contributions to classical philology. Volume 100). Hain, Meisenheim am Glan 1978, ISBN 3-445-01854-5 .