Board games of the Romans

Already at the time of the Roman Empire were board games a popular employment to recover from everyday distract and at the same time to make varied. Well-known and popular board games are described or listed here, as they were played by the Romans in ancient times . Circus games or theatrical performances , which were considered to be games in ancient times , do not fall into this category .

Some of the Roman games ( Latin ludus or lusus ) have survived to this day, others have "merged" in modern games. During the Empire, games of chance were forbidden in Rome because of the decline in morals and the gigantic stakes that ruined many and often led to brutal acts of revenge. All forms of dice games fell under the category of games of chance and were particularly frowned upon because they allegedly weakened the character and were generally considered improper and reprehensible. Nevertheless, they were played behind closed doors or in taverns with camouflaged rooms.

The term "game" and its social meaning

As Huizinga clearly defined in 1938, "playing" is a voluntary act or activity that is carried out within certain fixed limits of time and space according to voluntarily accepted but absolutely binding rules, has its goal in itself and is accompanied by a feeling of tension and Joy and an awareness of being different from ordinary life. "

From games , man has always been fascinated, it is still in its basic thinking, since the beginning of civilization play to want. Cave paintings already bear witness to this . People have always wanted to measure their skills against others and at the same time maintain social and communicative contacts. The game in the classic sense offers the best prerequisites for this, but at the same time it distracts from everyday life and offers the opportunity to diversify the leisure time.

Leisure time of the Romans

The Romans made a distinction between "otium" and "negotium". Otium referred to leisure, i.e. the time in which the Roman did not have to work (see also Senecas De otio ). Negotium, on the other hand, meant a time for him in which he could not freely dispose of his time, but had to fulfill his duties.

Games of the Romans

A popular saying first: Si tibi tessella favet ego te studio vincam (even if the luck of the dice is favorable to you, I will defeat you with the reflection). In ancient Rome, games were much more important than they are today. Games were part of everyday life, just like work. The children played on the street, the youngsters trained on the Tiber and the adults either sat on the steps of public buildings or were forced to meet at home, since, for example, dice games were completely forbidden in the times of the Republic, for social gatherings. The Romans, by and large, distinguished two types of games. Those of the circus , i.e. gladiator fights , animal hunts and big battles, also included big sporting events, chariot races , theater and fitness competitions. These games were primarily organized as spectacles for the people. The second group was the group of board games, for example Mora , Ludus (or Lusus) latronum and many more, which are described in more detail below.

Board games

At that time you didn't need a lot of utensils to pass the time. A few beans or small stones, a ball, a stick, a tire or a long leash (e.g. as a finish line) were enough for the children to have fun. The older ones needed almost even less.

Dice games and board games were particularly popular back then , although the exact rules of these are no longer known today. A game that is particularly well known to us, the mill , was also known back then under the term “merels”.

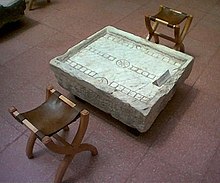

The grid game boards, which came from the Hellenistic era , mostly consisted of a grid consisting of several horizontal and vertical lines. This game table, which is similar to our today's checkerboard , was used for various games. For example, with the ludus latrunculorum (soldier, mercenary), a battle could be fought with 30 different pieces, which were either moved like pawns in chess (mandrae = simple piece) or could jump (latrones = elegant piece). Its winner was now allowed to call himself Imperator. It was not uncommon to see the winner of such a demanding game afterwards riding through the streets on the loser's back. Another version of this is called petteia , it was played either on an 8 × 8 or an 8 × 12 field board, but is mostly subject to the same rules. The ludus calculorum was also played on an 8 × 8 field board , in which the opponents had to try to place five of their stones in a row, whether horizontally, vertically or diagonally. (Practical: You could also use it as an abacus.) With 5 × 5 fields it was called pente grammai . Many of these games originally came from Greece .

You also played duodecim scripta (which also means twelve lines) and is similar to today's backgammon , but is played with three dice on a board with 12 lines in each of its own playing fields . Both parties were allowed to advance alternately from the first to the 24th playing field, with the moves being carried out according to a precisely defined schedule. In order to win, you not only needed luck with the sum of the dice, but also skill in handling the pieces that were to make the moves. However, the Romans did not develop this game themselves; they adopted it from the ancient Egyptian "Senet", but made it more exciting by refining the rules.

A variant of this game was the tabula , in which you could now hit the opponent's stones. In contrast to our backgammon today, it was still played with three dice. But this game, too, fell under state control of games of chance and was banned. However, that didn't work at the time either, and the game enjoyed great popularity in private circles or in taverns behind closed doors. This control was relaxed again during the imperial era; it was, for example, the favorite game of the emperor Claudius, who, since he liked to write, wrote a book about it or about gambling in general, which, however, has not been passed down.

The same gaming table can also be used just as well for playing dice and bones . The word alea , which is translated with dice, describes the throw itself, or the game of chance in general. Cubes were called tesserae . One was called canis , the dog, but the rest with its actual numerical value. These cubes were made of ivory or bone. During the game, dice were thrown either by hand or with a mug, with the mug being more popular as it reduced the chances of cheating, and two to three dice were thrown at the same time. In order to get luck on your side, one called either the name of a god or a goddess or his beloved, which naturally led to outbursts of cheerfulness among the young people and generally lifted the mood.

The game of chance with the small bones of the ankle, the so-called astragals ( ancient Greek : astragaloi "ankle"), was a little less combination possibilities, but no less enjoyable . The game Astragaloi , a variant of Pentelitha , was named after them. It is preferred to use the talus ( ankle bone , heel) of an animal, for example goat, sheep, antelope or calf, or it is made in the same form from metal, bone, ivory or stone. These Tali were rectangular in shape and accordingly only had four usable game sides, as the short sides were too small. Two of the side surfaces were very flat, the third concave and the fourth convex. Each of these sides had a different value: one (canis or vuturius), three, four (both named in Greek words only) and six (aenio). With the four pieces used, you could achieve 35 combinations each. The highest number of points (“Venus”) was achieved when all four ankles showed a different number.

The nuces castellatae was a much simpler game . Here you piled four nuts in a pyramid and had to try from a distance to bring them down by throwing more nuts at them. The players of a pentelitha needed even more skill . Here the players first took five astragals in their hands, threw them into the air and then had to catch them with the back of their hands, then toss them into the air again and catch them again from above.

The ludus deltae was also a game of skill, a triangle was drawn on the floor and divided into ten fields with horizontal lines. The smallest field at the top of the triangle received the value 10, the lowest field facing the player the value 1. Stones, nuts or other small objects were thrown from a distance of two to three meters. There were five rounds, the points were added up.

Likewise, you could throw a coin in the air, and while it was spinning in the air, a bet was made as to whether it would be upside down or with the ship on top. That was called capita et navia . The game par impar was very popular with young and old. One player had some nuts or small stones in his hand behind his back and the other had to guess whether it was an odd or an even number.

The games were later expanded to include card games, for example, by the Greeks and oriental slaves. Puzzles to challenge the mind were also particularly popular.

Gambling

- Duodecim scripta

- Tabula the direct precursor of backgammon

No gambling

- Astragaloi

- Latrunculi

- Loculus Archimedius

- Nuces castellatae

- Pentelitha

literature

- Ulrich Schädler : Games of mankind: 5000 years of cultural history of board games. Musée Suisse du Jeu, La Tour-de-Peilz and Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2007, ISBN 978-3-534-21020-6 .

- Hans Widmer: Roman world. Small illustrated cultural history. Buchner, Bamberg 1994, ISBN 3-9520192-1-6 .

- Anita Rieche : Roman children and board games. Württembergisches Landesmuseum, Stuttgart 1984.

- Jérôme Carcopino : Daily Life in Ancient Rome. Yale University Press Treble, New Javen 1940

- Roland Gregory Austin : Greek Board Games. In: Antiquity. Volume 14, 1940, 257-271 ( [1] online).

- Kenneth King, Henry Treble: Everyday Life in Rome. Oxford Press, 1930

Web links

- Play boards made of clay

- Video interview with Dirk Bracht from the Xanten Archaeological Park about Roman board games

Individual evidence

- ^ Huizinga, Johan: Homo Ludens, Reinbek near Hamburg, 1997, ISBN 3499554356

- ↑ Fritz Schalk : , Otium 'in Romansh. In: Brian Vickers (ed.): Work, leisure, meditation. Reflections on 'Vita activa' and 'Vita contemplativa'. Verlag der Fachvereine, Zurich 1985, pp. 225-256.