Board game

A parlor game is understood to be a form of activity that usually serves to pass the time and is fun, which is practiced together with other participants, often in the form of a competition , according to predetermined rules, mainly with the help of game material. The game material used, such as playing cards and the game board, is particularly different from other forms of play such as sporting play .

Definition of terms and word origin

Most parlor games are board games or card games . Typically, writing games , guessing games or charades are also included . Board games range from pure games of chance (for example, many dice games) to brain games or games of skill ( chess and Go , role-playing games or catch and hide ) to various party games such as spin the bottle and - with a centuries-old tradition - blind cow .

In some cases, the delimitation of parlor games is made narrower, for example only containing games "that are played on the table with the help of game plans , figures and other material", so that in particular pure card games are excluded. In this case, the terms are party game and board game largely synonymous. The Libro de los juegos , the “Book of Games” written in 1283 on behalf of the Castilian King Alfonso the Wise , already distinguishes it from sporting games. There board and dice games are characterized by the fact that they are played while sitting, unlike the sporting game that is played on foot or on horseback.

The name board game comes to the expression parlor back for a salon in civil and noble houses of the modern era. The term was later extended to an entertaining game "played by several children or adults together."

Historical development

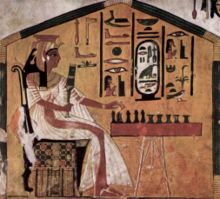

The oldest evidence for board games are pictorial representations of players as well as unearthed game plans from ancient Egypt , there mostly as grave goods , and from Babylonia . However, there is generally no doubt that games have already been played, for example on playing fields drawn in the sand, as is still common today in Mancala games in Africa (see picture in the following picture line). One on the royal cemetery of the Sumerian city of Ur excavated Schedule of the Royal game of Ur v in 2600-2400. Dated. 2006, 3500 years old, from was wooden and ivory -made Senet game excavated. The game is a little older than the Senet games that were found in Tutankhamun's tomb .

The oldest board games still in use today are Go and Mühle , both of which were definitely played before the turn of the century . Chess and the games of the Mancala family have a tradition that is over a thousand years old .

Is in the form of preserved for Dice Game dice , secured a more than 4,000-year history.

Card games, which can be proven in Europe through traditional bans from the 14th century, are much more recent. However, historians assume that the tradition of playing cards has its origins in China and India, where paper production was the basis for card production much earlier .

Board game without a board: children in Nigeria play the Mancala version of Ayo

Royal game Ur (2600 to 2400 BC) in the British Museum

Playset from Amenhotep III. († approx. 1350 BC)

One of the first games to be commercially produced and sold in the 19th century with a printed graphic as a game plan was the goose game , which can be traced back to the 16th century .

Early examples of commercial board games in Europe, some with a well-known author's name, are the Snakes and Ladders (ladder game) sold in England from 1892 , Reversi marketed by Ravensburger from 1893 , Salta sold from 1899 , and 1910 based on the Indian board game Pachisi , don't get angry , the Laska, invented by the world chess champion Emanuel Lasker in 1911, and the game Catch the Hat, created in 1927 in the modern Bauhaus design .

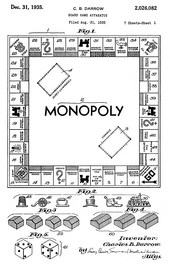

In the United States, commercial board games were marketed by publishers such as Parker and Milton Bradley (MB) from the second half of the 19th century . The classic Monopoly , which was based on a model patented in 1904, The Landlord's Game , was produced in large numbers from 1935 . An important impulse came from games that were released after 1960, including Risk (risk) (1959), which The Game of Life (The Game of Life) and as part of 3M's Edition games like Acquire and TwixT . The authors of the last two games mentioned, Sid Sackson and Alex Randolph , had a significant influence on the further development of parlor games, especially in Germany, with titles such as Sleuth , Focus , Can't Stop and Metropolis and Sagaland in the following decades , Get the vultures , incognito and ghosts .

In the 1980s, Europe and especially Germany became known as the manufacturer of a new type of board game aimed at family-friendliness. Funded not least by the Game of the Year award, which has been given annually since 1979, and later also the German Games Prize .

The popularization of video recorders found expression in the since 1983 annually by in Germany Friedhelm Merz Verlag in Essen organized international game fair "GAME" .

The term German Game , which is used for author games , was coined by the Anglo-American language area. This term has been used less and less since the beginning of the 21st century in the wake of the ever greater networking of the international game scene and the emergence of successful game publishers from other European countries with publishing programs of a basically similar type and increasingly replaced by the term Eurogame .

The growing self-confidence of game designers can also be seen in the so-called "beer mat proclamation" signed by twelve game designers and one game author at the Nuremberg Toy Fair in 1988. It expresses the requirement that the names of the people who invented the game be named on the game box.

The game Settlers of Catan marks a milestone in the further popularization of parlor games , and has been sold more than 30 million times since it was first published in 1995, including variants, extensions and translations in over 40 languages.

Classification of parlor games

Board games are different ways classifiable . The differences result from the degree of abstraction and the perspective on which the delimitations are based. The following description of various classification schemes also serves to illustrate the variety of parlor games. The details of the games listed as examples can be found in the linked articles.

An early division of games into three classes is explained in the Libro de los juegos from 1283 on the basis of three exemplary games: chess decided by the intellect, the game of dice decided by chance and the trick track that requires reason , in which "the right cleverness in it [insist] to use the mind so that one realizes that it brings the most advantage, but to use luck when it is good to one and limit the damage as best as possible when it is not suitable for one . "

Game theory classification

A very rough classification of parlor games is made possible by the properties that are also the subject of the game model of mathematical game theory :

- Do the rules of the game provide for random decisions , for example with the help of a die ?

- In contrast to rock-paper-scissors , are there sequential decisions by players within the framework of move orders , so that there is a comparatively large number of possible combinations for these moves ?

- Are there game situations in which the players have different information about the course of the game so far, for example in Skat ?

Apart from the game theoretical formalism, the answers to the three questions characterize how the players' subjective uncertainty about the further course of a game arises. In this way, there is a demarcation between luck, logic and bluff components within a game and consequently a classification of the parlor games. This classification, usually shown in the form of a triangle, less often as a point scale, does not take into account the factors of manual dexterity or speed of reaction , which are, however, the exception in parlor games , for example in Mikado or Speed .

It turns out that intellectual competition games such as chess and go are all games for two people that have neither luck nor bluff components (so-called purely combinatorial games ), but are exclusively characterized by the difficulty, given the combinatorial variety of possible moves to find the optimal move . In relation to the triangle representation, all popular board games are located on two of the three corners (pure games of chance and pure combinatorial games), two of the three edges (games with perfect information and random-free games) and the middle area (games with all three components of uncertainty).

Even less differentiating is the frequent distinction between games of chance and games of skill, with a continuum of mixed games in between. This classification is particularly relevant for the legal delimitation of games of chance . This summarizes the influences of random decisions and the imponderables that arise for the players through different information levels , such as in a card game in which everyone only knows their own cards . In this regard, board games such as Diplomacy , Stratego and Geister show that different levels of information, unlike card games, are not necessarily linked to the existence of random decisions.

In addition to the three features described, three other game properties, which are also the subject of mathematical game theory, allow additional classifications:

- The number of players

- Permission to communicate, especially for the purpose of cooperation , such as in the Scotland Yard game (there against a single player), or in cooperative games such as the bear game (where all players usually cooperate) and

- the zero-sum property , which is usually given except in cooperative games. It encompasses the fact that the sum of the (positive) winnings of players always corresponds in amount to the sum of the losses of players.

Another distinguishing feature is whether the rules of the game for the players are symmetrical (such as rock-paper-scissors , also chess in the case of a draw for the right of suit), symmetrical except for the right of the first move, or even further asymmetrical (such as fox and geese and Scotland Yard ).

Classification according to further criteria

Further characteristics of games that are suitable for classification are:

- Year of publication or epoch,

- Place of origin, which at least in the case of classic games contains a cultural context,

- Requirements for the game, usually in the form of a recommended playing age,

- Equipment and game material ( board game , card game, dice game ),

- Information about the approximate playing time,

- principal aim of the game (for example a race or a fight in which the “survivor” wins).

- Degree and type of requirement for the players, often depending on the scope of the rules .

On the basis of such criteria, Erwin Glonnegger differentiates between racing games, spiral running games, games of chance, letter placement games, picture placement games, domino- like placement games, business games, crime games, siege games, placement games and another eight game classes, each of which is dominated by a game that is dominant due to its high distribution represented: Pachisi , Chess , Go , Mill , Checkers , Backgammon , Mancala and Halma .

Classification of the German game archive

The classification of games in the German Games Archive distinguishes between board and table games, card games, and dice and random generators.

Board and table games

The board and table games are subdivided into a two-level classification scheme, which comprises seven upper classes:

Dice and games of chance with pure dice games like Kniffel , start-finish games like Mensch är är dich nicht , search and catch games like Catch the Hat and tactical dice games like Can't Stop .

-

Placement games

with drawing games ( dominoes ), letter placement games ( Scrabble ), number placement games ( Rummikub ), tactical placement games ( Café International ), lotto games ( bingo and derived children's picture lottery games), figure placement games ( tangram ) and picture placement games ( puzzle games ). - Mind games

with strategic mind games (chess), tactical- topological mind games ( Halma ), combination and decoding games ( mastermind ), memory games ( memory ) and solitaire games ( solitaire ).

-

Role-playing games

with "parlor games" (here in the narrower sense meant by a reference to life in all its everyday life as in the game of life ), business games ( Monopoly ), crime and agent games ( Scotland Yard ), adventure games ( Alaska ), war and conflict simulation games ( Risk ), fantasy and science fiction role-playing games ( Das Schwarze Auge ), sports and racing games ( Jockey ), traffic games ( Stop & Go ) and travel games ( Deutschlandreise ). -

Quiz and conversation games

with guessing and quiz games ( Barbarossa and the riddle masters ) as well as psychological and conversation games ( sympathy ).

- Skill and action games

with skill games ( Mikado ), action games ( Avalanche ), reaction games ( Spitz watch out ) and sports games ( Tipp-Kick ). - Other games

with Varia and game magazines.

Card games

When it comes to classifying card games, the German Games Archive is based, among other things, on the German Playing Card Museum . On the one hand, there is a material-related categorization of playing cards which, like traditional playing cards, can be used universally for different games. On the other hand, card games that use a specially designed card set are classified in two levels, analogous to board games, with three main categories:

- Abstract games

with possession games ( bridge ), eye games ( skat ), discard games ( rummy ) and card combination games ( poker ).

- "Role play" (in a broader meaning than usual, see role play )

subdivided into genres such as " parlor games" (i.e. with reference to life in all its everyday lives), business games ( horse trading ), crime and agent games ( Sherlock Holmes ), Adventure games, war and conflict simulation games, fantasy and SF role-playing games, sports and racing games, and traffic games. - Communication games

such as question and answer games, quiz games , fortune telling cards ( tarot ) and creative games (the laying of cards serves as the basis for entertaining associations for the players).

Classification by BoardGameGeek

The world's most comprehensive online database for board games, BoardGameGeek , which was founded in 2000, distinguishes eight types ( types or subdomains ) and - by no means to be regarded as exhaustive - around 50 mechanisms and over 80 categories.

The three divisions are not hierarchical , but take place in parallel. None of the three classifications is disjoint . For example, the board game is risk in the two types of family game and war game and in the two categories war game and field assurance ( Territory Building sorted). Furthermore, mechanisms such as rolling the dice , throwing players out , moving to neighboring fields and area control by majority overweight are assigned to the game. The game Settlers of Catan is divided into the two types family game and strategy game as well as into the two categories economy and negotiation . In addition, various mechanisms such as dice , hex game board , network structure and modular game board are assigned to the game .

Types

The eight types are:

- Abstract games:

Mostly without the influence of chance, this includes all classic board games such as chess, mill, Halma and backgammon, but also author games such as Focus and TwixT . -

Family games :

Relatively simple rules with limited playing time. Random influences make it possible for children and adults to have largely equal opportunities to play and be entertained, as it were. The topics of war and combat and the premature retirement of other players are avoided. Probably the most popular example is Settlers of Catan . -

Themed games , unofficially Ameritrash :

The underlying theme, often associated with high violence, is the visual focus of the game design. One example is Battlestar Galactica . -

Children's games :

games that are only of interest to children due to the simplicity of their game rules. -

Party games :

Short and fast-paced games with simple rules, also suitable for a large number of players. Examples are Tabu and Trivial Pursuit .

-

Strategy games , unofficially Eurogames : The

main characteristic is a complex set of rules with a relatively high degree of abstraction. If the influence of chance is low, the demands on the players are high. Examples are 1835 , Imperial , Caylus, and Puerto Rico .

-

War games :

These games are thematically based on historical and fictional armed conflicts, including conflict simulations ( CoSims ). The playing figures often represent military units as in the "classics" of this type Risk , Diplomacy and Stratego .

- Customizable Games ( Customizable Games ):

Games, which are characterized by a high number of extensions. This includes in particular trading card games such as Magic the Gathering .

Mechanisms

The 50 or so mechanisms relate to the way the game progresses. In particular, it covers:

- Features related to the game material such as the use of dice, an initial deck of cards, a game board in regular (chess), irregular ( risk ) or modular ( Settlers of Catan ) form and of paper and pencil ( Racetrack ).

- Rules for changing the state of the game such as moving a piece according to the die result, with simultaneous decisions, with multiple selection of a moving or otherwise "acting" piece, with moves that are only allowed on neighboring fields ( risk ), with a bid in an auction, when placing of game pieces ( mill ), when drawing lines and when connecting fields ( steam horse ).

- Evaluation rules for move decisions as they are used when capturing a piece (chess, stratego ), with an area enclosure (Go), with an area control by majority overweight and with a rock-paper-scissors-like evaluation ( diplomacy ).

Categories

The over 80 categories are mainly based on the game theme, with around 20 different historical epochs such as the Middle Ages , First and Second World War being represented. The other topics such as mafia , sports , railways , space travel , science fiction , religion , seafaring , animals and races are even more diverse . In abstract games, the division is based on dominant game elements such as dice, cards, bluffing, memory characters, puzzles, numbers and words.

List of individual games

See list of games .

Gaming magazines and reviews

Various magazines are devoted to the topic of board games. In the German-speaking countries these are currently mainly the magazine Spielbox, founded in 1981, as well as Spielerei und Fairplay .

The game reviews, which make up part of the content of game magazines, were previously only available in daily and weekly newspapers. With an article “Dem homo ludens ein Gasse”, Eugen Oker began a first regular column in 1964 about games in the time , the contributions of which achieved “a special meaning and external effect”. From 1972 Oker's reviews appeared in the Frankfurter Rundschau , and Bernward Thole wrote game reviews first for Die Zeit and later for the Frankfurter Rundschau .

Archives, museums and research

Various institutions are dedicated to the systematic and scientific examination of the subject of games and games , known as ludology . In the DA-CH countries, these are in particular the German Games Archive in Nuremberg, which emerged from a private initiative by Bernward Tholes in Marburg, the Swiss Games Museum near Montreux, the Institute for Game Research and Playing Arts at the Mozarteum University in Salzburg and the Institute for Ludology at the SRH Berlin University of Applied Sciences . Be mentioned in this context is also the scientific Open Access -Fachzeitschrift Board Games Studies Journal .

Successful game designers

See: Game Designers

See also

literature

- Erwin Glonnegger, Claus Voigt, Johann Rüttinger, Kathi Kappler: The game book Board and placement games from all over the world, origin, rules and history. Ravensburger, Ravensburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-473-55654-0 .

- Harold JR Murray: History of Board-games Other Than Chess. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1952.

- David Parlett : The Oxford History of Board Games . Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, NY 1999, ISBN 0-19-212998-8 .

- David Pritchard: The big family book of games , trans. Tom Werneck , Munich 1983, ISBN 978-3-570-01011-2

- Ulrich Schädler : Games of Mankind: 5000 years of the cultural history of board games , on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Swiss Game Museum (1987–2007), Musée Suisse du Jeu , La Tour-de-Peilz / WBG , Darmstadt 2007, ISBN 978-3 -534-21020-6 .

- Ulrich Vogt : The die has been cast - 5000 years around the cube , Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim - Zurich - New York 2012, ISBN 978-3-487-08518-0 .

Web links

- Link catalog on the topic of board and table games at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Luding game database

- BoardGameGeek : Database (and more) about games

swell

- ↑ Erwin Glonnegger: Das Spiele-Buch , Drei Magier Verlag , extended new edition 1999, ISBN 3-9806792-0-9 , p. 6.

- ↑ The Book of Games . Alfons X. "the Wise", translated and commented by Ulrich Schädler and Ricardo Calvo , Lit Verlag, Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-643-50011-3 , p. 53 in the Google book search.

- ↑ Duden (orthography), keyword parlor game , accessed on May 20, 2018

- ^ Trustees of the British Museum: The Royal Game of Ur. The British Museum, accessed July 28, 2019 (British English).

- ↑ Board game in the grave . In: Der Spiegel . No. 16 , 2006, pp. 133 ( Online - Apr. 15, 2006 ).

- ↑ Michael Koulen: Go. Die Mitte des Himmels , Cologne 1986, p. 10 ff.

- ↑ Hans Schürmann, Manfred Nüscheler: This is how you win mill . Otto Maier Verlag, Ravensburg 1980, p. 4.

- ↑ Ulrich Vogt: The die has been cast. 5000 years around the cube ; Hildesheim 2012, p. 17

- ^ Hugo Kastner, Gerald Kador Folkvord: The great Humboldt Encyclopedia of Card Games, Baden-Baden 2005, p. 14.

- ↑ Manfred Zollinger, Zwei unbekannte rules des Gänsespiels , Board Games Studies, Volume 6 (2003), pp. 61–84 ( online )

- ↑ Erwin Glonnegger: The games book. Board and placement games from all over the world, origin, rules and history , Drei Magier Verlag, Uehlfeld 1999, ISBN 3-9806792-0-9 .

- ↑ Bruce Whitehill, Games of America in the Nineteenth Century , Board Game Studies Journal, Volume 9, 2015, pp. 65–87 ( online )

- ↑ Bruce Whitehill: American Games: A Historical Perspective , Board Games Studies, Volume 2, 1999, pp. 116–142 ( online )

- ↑ Stewart Woods: Eurogames. The Design, Culture and Play of Modern European Board Games , Jefferson, NC, 2012, ISBN 978-0-7864-6797-6 , p. 32 in the Google book search

- ↑ Zooloretto is Game of the Year , Telepolis, June 25, 2007, accessed on May 29, 2017

- ↑ Stewart Woods: Eurogames. The Design, Culture and Play of Modern European Board Games , Jefferson, NC, 2012, ISBN 978-0-7864-6797-6 , in particular Chapter 4 ( From German Games to Eurogames ) pp. 63-78.

- ↑ Games authors' guild: Historical review

- ↑ Steffen Bogen: Playing with rules . In: Karen Aydin, Martina Ghosh-Schellhorn, Heinrich Schlange-Schöningen, Mario Ziegler (eds.): Games of Empires: cultural-historical connotations of board games in transnational and imperial contexts . Berlin ; Münster, ISBN 978-3-643-13880-4 , pp. 365 ff . ( P. 365 in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Export hit from the Odenwald: 25 years "Settlers of Catan". In: hr.de. January 20, 2020, accessed May 7, 2020 .

- ↑ The Book of Games . Alfons X. “the Wise”, translated and commented by Ulrich Schädler and Ricardo Calvo, Lit Verlag, Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-643-50011-3 , p. 54 in the Google book search.

- ↑ Jörg Bewersdorff : Luck, Logic and Bluff: Mathematics in Play - Methods, Results and Limits. Vieweg + Teubner, 7th edition 2018, ISBN 978-3-658-21764-8 , doi: 10.1007 / 978-3-658-21765-5 , pp. V – VIII ( online )

- ↑ Dagmar de Cassan: The Book of Games 2005 ( online )

- ↑ Hartmut Menzer, Ingo Althöfer: Number theory and number games: seven selected topics. Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-486-72030-3 , p. 322 in the Google book search, doi : 10.1524 / 9783486720310.321

- ^ Hugo Kastner: Learning with games: Advice for parents, educators and teachers. Hannover 2010, ISBN 978-3-86910-609-0 , p. 239 in the Google book search

- ↑ Nils Hesse: Win by playing: Winning strategies for the 50 most famous card, dice, board and prize games. Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3-658-04440-4 , p. X in the Google book search, doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-658-04441-1

- ↑ WIN, the game journal. January 2014, ISSN 0257-361X , p. 36 f. ( online )

- ↑ Hartmut Menzer, Ingo Althöfer: Number theory and number games: seven selected topics. Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-486-72030-3 , p. 321 in the Google book search, doi : 10.1524 / 9783486720310.321

- ^ Tom Verhoeff: The Mathematical Analysis of Games, Focusing on Variance. In: MaCHazine, 13 (3), March 2009. A detailed version was published in Dutch: Spelen met variantie. ( Memento from June 30, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Pythagoras, 49 (3), January 2010, pp. 20-24.

- ↑ Clemens Weidemann, Hans Schlarmann: The examination of predominantly random dependence in gambling law - illustrated using the example of Hold'em poker and other card games. New Journal for Administrative Law - Extra, Volume 33, October 15, 2014, pp. 1–8 ( online )

- ↑ Jörg Bewersdorff: Games between luck and skill. Journal for betting and gambling law, 2017, pp. 228–234, there p. 230 f.

- ↑ Udo Winand: Game Theory and Business Planning. Berlin 1978, ISBN 3-428-04012-0 , p. 102 ff. In the Google book search

- ↑ Jörg Bewersdorff: Luck, Logic and Bluff: Mathematics in Play - Methods, Results and Limits. Vieweg + Teubner, 7th edition 2018, ISBN 978-3-658-21764-8 , doi: 10.1007 / 978-3-658-21765-5_4 , p. 346

- ↑ a b c How can games be classified? Summary of a lecture by Wolfgang Kramer , online

- ^ Erwin Glonnegger: Das Spiele-Buch , Drei Magier Verlag , extended new edition 1999, ISBN 3-9806792-0-9 , table of contents, p. 5.

- ↑ Classification of board and table games ( Memento from October 4, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Classification of card games ( Memento of October 4, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Board Games subdomains on boardgamegeek.com , accessed April 13, 2020

- ↑ a b mechanism on boardgamegeek.com , accessed April 14, 2020

- ↑ a b Board Game Categories on boardgamegeek.com , accessed April 14, 2020

- ↑ Risk (1959) on boardgamegeek.com , accessed April 14, 2020

- ^ Catan (1995) on boardgamegeek.com , accessed April 14, 2020

- ↑ a b Thematic Games on boardgamegeek.com, accessed April 13, 2020.

- ↑ Eugen Oker: Dem homo ludens ein Gasse , Die Zeit, 1964/49, December 4, 1964, online

- ↑ Bernward Thole: Outlines of a game review , in: Homo Ludens. Der spielende Mensch, Volume 2, 1992, Hochschule Mozarteum , Salzburg, pp. 15–42.

- ↑ Games critic. In: eugen-oker.de. Retrieved May 8, 2020 .

- ^ "An alley for homosexuals". For the founder of the German Games Archive on his 80th birthday. In: museenblog-nuernberg.de. Retrieved May 8, 2020 .

- ^ German game archive. Retrieved May 9, 2020 .

- ↑ Swiss Game Museum. Retrieved May 9, 2020 .

- ^ Institute for Game Research and Playing Arts. Retrieved May 9, 2020 .

- ^ Institute for Ludology. Retrieved May 9, 2020 .

- ↑ Board Games Studies Journal: Volumes 1 to 9 (1998−2015) , from Volume 10 (2016−)