Othello (game)

| Othello Reversi |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Game data | |

| author | Lewis Waterman |

| Publishing year | 1880s |

| Art | Board game |

| Teammates | 2 |

| Duration | 5-60 minutes |

| Age | Recommended for ages 5 and up |

Othello and Reversi are two closely related strategic board games for two.

history

In the 1880s, the Englishman Lewis Waterman developed a board game that he called Reversi ( Latin for "the upside down"). It was played on a chess board with 64 fields. His game was similar to the Game of Annexation ("The Annexation Game "), which was invented by the Englishman John W. Mollett. However, Mollet's game was played on a cruciform board. Both lived in London and claimed to be the real inventors. There was a legal battle.

The oldest known source on Waterman's Reversi is a newspaper article from August 21, 1886 in "The Saturday Review". After Walter H. Peel published some articles about Reversi in the magazine “The Queen” under the pseudonym “Berkeley” in 1888, the game became better known. Other publications quickly followed, including the "Handbook of Reversi" by Peel, which was published in 1888 by Waterman's company Jacques and Sons and which saw several new editions in the following decades.

The Ravensburger company has been selling Reversi game boards since 1893 and launched several family-friendly editions such as “Räuber und Gendarm” or “Dreh das Ding”. Reversi, which is a registered trademark of Ravensburger, is one of the most successful games of modern times. Reversi has always remained well known in the English-speaking world. So occupied z. For example, the English game historian RC Bell with Reversi, and the American science journalist Martin Gardner initiated a discussion in the journal "Scientific American" in April 1960 about the shortest possible Reversi game.

In 1971 the Japanese Gorō Hasegawa ( 長谷川 五郎 ) registered the variant Othello in Japan as a trademark without, as he claimed, having had knowledge of Reversi. His father was an English teacher and suggested this name because of the analogy to Shakespeare's Othello .

The most important differences are that in Othello the first four stones are set as the opening, and in Reversi each player has exactly 32 stones. In Germany, Reversi is often played in such a way that only one row is turned over. Originally, however, in Reversi, as in Othello, every enclosed row was conquered.

Today, along with Shogi , Go and Renju , Othello is one of the most popular board games in Japan and is played by around 25 million people there. In Europe and North America there was no great success. Instead, Reversi is often sold here with the indication that you can play it with modified rules.

Othello is the game with the most annual world championships (since 1977) under license regulations. At tournaments in Germany and the Netherlands, Othello boards are mostly used, as sold by the Universal Trends company in Germany. The even larger boards from the Japanese publisher Megahouse (formerly Tsukuda) are used for world championships.

With the development of computers, the quality of the game increased, and thanks to its simple rules, Othello is becoming increasingly popular as a computer and online game (mostly under the name Reversi or new creations such as “Drehum” or “Revello” for licensing reasons). Since the turn of the last century, the number of recreational and tournament players has increased significantly with the spread of the Internet.

regulate

On an 8 × 8 board, the players take turns placing pieces, the sides of which are colored differently (black and white). One player ("white") always places his stone with the white side up, the other ("black") with the black side up. At the start of the game there are four stones in a given order on the board. A player must place his stone on an empty space that is horizontally, vertically or diagonally adjacent to an already occupied space. When a piece is placed, all opposing pieces between the new piece and an already placed piece of your own color are turned over. Moves that do not lead to the opposing stones being turned over are not permitted. The aim of the game is to have as many pieces of your own color as possible on the board.

The exact rules:

- It is played on a board with 8 × 8 fields.

- In the Reversi variant , each player has a supply of 32 stones at the beginning, in Othello the number of stones is unlimited.

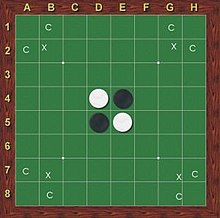

- Only applies to the Othello variant : Before the start of the game, two white and two black stones are placed on the middle fields of the board, two diagonally opposite each other with the same color (picture).

- Only applies to the Reversi variant (Jacques and Sons): In the first two moves, both players place one of their stones (red or black) on the four middle fields. There can therefore be two “starting positions”, whereby the second player can de facto choose one.

- Only applies to the Reversi variant (Ravensburger): In the first move, both players place two of their stones (colors depending on the edition, e.g. red and green, white and red, red and yellow) on the four middle squares. There can therefore be two “starting line-ups”, whereby the first player can de facto choose one.

- The players take turns, Black begins (Jacques and Sons: Red). Either you set a stone of their color to the top of an empty field, or you fits . Passing is only allowed, however, if there is no rule-compliant opportunity to place a stone.

- You can only bet in such a way that starting from the stone you have placed, one or more opposing stones are connected in any direction (vertical, horizontal or diagonal) and then your own stone is placed again. So at least one opposing piece must be enclosed by the piece you placed and another piece of your own in a straight line. All fields between the two own stones must be occupied by opposing stones.

- All opposing stones that are enclosed in this way change color by being turned over. This happens as part of the same turn, before the opponent's turn. A train can include several rows of opposing stones at the same time, all of which are then turned over. However, if a piece that has just been turned over includes other opposing pieces, these are not turned over.

- If the players pass one after the other, i.e. when no one can place a stone, the game is over. In Reversi, this is the case when both players either run out of stones or cannot turn over any opposing stones.

- The player who has the most stones of his color on the board at the end wins. If they both have the same number, the game is a tie.

- There are various rules to determine the amount of profit. Usually the fields that are still empty at the end of the game are credited to the winner, i.e. added to the difference in the number of stones.

- With an additional rule that is often used in Japanese tournaments, you can avoid a tie: A player (who is, for example, drawn) determines whether an equal number of stones at the end of the game is counted as a victory for white or black. The other player then chooses a color.

Pragmatic rules for games without computer assistance:

- Once a piece has been placed, it cannot be removed from the board.

- If a player has wrongly turned a stone or forgot to turn one, this can be corrected by both players until the opponent has made his next move. Then wrong or not turned stones remain.

strategy

stability

Having positioned a corner stone has the advantage that this stone can no longer be looted by the opponent, since it cannot be surrounded by opposing stones and thus turned over. Such a stone, which can no longer change color, is called a stable stone ('stable disc'), because its color is stable in the further course of the game. Starting with a stable stone, you can often annex adjacent stones, which can also become stable stones.

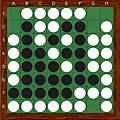

In Fig. Stable discs you can see the starting position before the last two moves. White still has 20 stones, half of which are stable and can no longer be turned. However, the stones in the A and B columns and the row of eight are not yet stable. Now only Black can move, and only on A8 . White immediately loses stones B7, B8, C8 and D8 . These stones are now stable for Black. With the last move, Black takes all of the pieces in column A. White thus loses all unstable stones.

X and C fields

Some fields have special names because they have special meaning in the game. These are the fields next to the corners: The field on the diagonal in front of the corner is called the X field ( B2, B7, G2, G7 ), the other two fields that border the corner are C fields ( A2, B1 , A7, B8, G1, H2, H7, G8 ).

Within the playing field, different regions are differentiated according to the principle of the cardinal points. The region around corner H1 is known as the north-east region.

Mobility, speed, walls and quiet trains

In the last section the value of owning corners and generally stable stones as well as the danger of betting on x and c squares was explained. So there are good and bad moves in the middle game. You can use it to formulate the strategic goal of forcing your opponent to make bad moves and to avoid being forced to make bad moves yourself. This can be achieved by moving in such a way that many (good) moves remain or are opened to you, but only a few (bad) moves are available to the opponent; they say: maximize your own mobility and limit the mobility of your opponent.

This strategy is extensive in the sense that if at any point in time your mobility is high and that of the opponent is low, you are generally flexible enough to find a move that will maintain that state, whereas your opponent will find it difficult to make a good move will find that increases his mobility and reduces his own. It therefore makes sense from the beginning of the game.

If a player succeeds in creating a very strong mobility imbalance in his favor, it is said that he has gained control: his opponent always has very few options, or he even has to sit out. In this way, as a beginner, you lose against very superior players or good computer programs.

Othello is therefore a game in which one would often like to sit out: Every move you make has the tendency to open up new options for your opponent and to use up your own options. If I move, my opponent can usually respond well to this move, and I have the problem of finding a move again. Positions can hardly be evaluated if it is not known who is to move: In general, a given position is worse for White when it is White to move than when it is Black. This phenomenon is paraphrased with the term speed : One speaks of speed gain if one manages to steer the unpleasant move search on the opponent. A speed move is a move that is difficult to answer and thus forces the opponent to search for a move. You have a speed advantage when it is your opponent's turn and you have fewer or as many (!) Speed moves as you yourself.

In Fig. Mobil1 a situation is shown illustrating the concepts mobility and pace Black can be very strong after a7 draw: This limits the mobility of White significant one: The trains d8 , g5 and d3 are no longer available. The moves b7 and b8 are very unfavorable because they immediately lead to the loss of corner a8 . This effectively leaves White with only two options: g6 and d2-e2-f2 . However, Black has two speed moves a3 and a2 , and it is White's turn! Therefore White will run out of moves first and White will be forced to give up corner a8 .

Walls and quiet trains are terms that help to implement the mobility strategy. Walls in your own color are unfavorable because you don't have any opportunities to move there, but your opponent does. In Fig. Mobil2 , the move f8 would be disastrous for Black, since Black would use it to build a wall and thus massively reduce his own mobility.

A quiet move is a move that changes the board as little as possible, typically by turning one stone, preferably an inner one. Such moves are cheap because they come very close to skipping and open few new moves for the opponent. In Fig. Mobil3 Black can play a quiet move with d3 . The search for, the preparation of and the thwarting (poisoning) of quiet trains is above all characteristic of the opening.

Edge strategy

With stones that are on the edge, there are only a few adjacent fields and therefore fewer opportunities to turn these stones over. In addition, the edge offers access to the corner with the help of the c-fields that are also on it. Together with the corner, you can often take over a large part of the edge and thereby obtain stable stones. It is therefore important to think early on whether you want to position your stones on the edge, as your own good edge position or a weak edge position of the opponent towards the end of the game can mean a great advantage.

It is generally not recommended to have a lot of stones on the edge - it is often a disadvantage. Plays z. B. White initially puts two stones on the edge so that only one space is free between them, then Black can play on this free space and thus get a wedge. How useful such a wedge can be can be seen from the example of a weak edge position, the so-called unbalanced five , as can be seen in Fig. Edge1 . If White takes the corner in the position shown, Black can secure a wedge on b8 and thus create the opportunity to take over the entire edge and the next corner with h8 (see Fig. Edge2 ). However, unbalanced five are not always a disadvantage. If only white has access to the free c-square and black does not, then white can make a speed move and at the same time achieve a more stable edge position with six pieces. In this case, this position is definitely desirable.

A distance of three free spaces between two of your own stones can also be very dangerous. Let us consider a position with white pieces on squares c8 and g8 . Black can now threaten to take over the corner with a piece on f8 , as can be seen in Fig. Edge3 . If White defends this attack on e8 , Black gets a wedge on d8, with which he has the opportunity to get the corner h8 ( Fig. Edge4 ).

Basically, one can say that an edge position with two own stones with an uneven distance is much easier to attack than a position with an even distance. However, one must also take into account that the theoretically correct field is often not playable because there is no access. Then you either have to try to gain this access or play an alternative stone.

parity

At the end of the game, smaller regions are usually created. These regions are groups of open spaces, usually between two and six stones, which are usually located around the corner. The player who makes the last move in such a region has an advantage because he is the last to turn over stones and these are more stable.

In Fig. Parity1 there are only two stones left to play and it is Black's turn. Regardless of where Black bets, he loses 28 to 36. If it is White's turn, Black wins 36 to 28. This means that White has a small advantage in the endgame, as it normally places the last piece. Black can avoid this advantage by suspending once within the game. If there is an even number of missed moves, the advantage is of course canceled out. Since it is usually very difficult to force a player to sit out, there is another way to influence parity in your favor. For this a player has to manage that his opponent cannot play in a region. So the player gets several moves in a row in a region. In terms of parity, this means that the player should try to force them to place the last stone in a region. If several regions are free, he can also influence the parity in other regions in his favor.

As you can see in Fig. Parity2 , the white player has no way to play in the lower right region. If Black now bets in this region, White can force parity for the other two regions by then placing a stone in the upper right corner. Regardless of which region Black plays in, White has the last move and wins by 38 to 26. If instead Black plays g2 and voluntarily surrenders the corner h1 , he will force parity in all three regions. So if g2-h1-g1-a1-a2 are played, Black now ends with g8 and wins 37 to 27.

Often the best move is not immediately apparent. In Fig. Parity3 , the move b7 leads White to bet b8 without giving Black access to a8 . Black would have to play in a different region and accordingly give up parity in all four regions. Black would lose 22 to 42. If, on the other hand, Black plays the less intuitive move b2 , it loses a corner, but can play to b7 after the move of the white player, who will presumably go to a1 . White can no longer block black in the lower left region. Black gets the last move and thus parity. Since Black has the last move in the region, White must now play in the other regions first. Black has achieved parity in three of four regions and wins 40 to 24.

Endgame

The endgame is the last section of the game in which most of the board is already filled with stones. Most of the time, u. a. the previously unreachable corners and some of the x and c squares that the players avoided in order to prevent the opponent from accessing the corner.

In the middle game, the final evaluation of a position is usually not possible because a number of possible game courses which grows exponentially with the number of moves still to be made would have to be examined. Since this would overwhelm even computers and experienced players, the chances of winning can only be assessed on the basis of criteria such as stability, mobility or parity. In the endgame, on the other hand, the number of possible moves and the total number of moves still to be made has decreased to such an extent that the further course of the game becomes clear. Due to the lack of other possibilities to move, at some point in the game one of the players will be forced to give his opponent access to a corner, for example by occupying an x-square. In order to keep the negative consequences of such a corner loss within limits, combinations that lead to a corner swap are popular. A player sacrifices a corner to the opponent in order to then take another corner himself. In this way, one can often catch up or even achieve an advantage with regard to the filling of the edges.

A popular target for an offer to exchange corners is the arrangement of the unbalanced five already mentioned in the section on edge strategy. By occupying the x-field, the opponent sacrifices a corner next to the still free c-field, in order to then place his own stone as a wedge on the c-field and later to take over the other corner and the entire edge as stable stones. However, this blow will only succeed if the opponent accepts the victim and occupies the corner offered to him. As long as he has better moves to choose from, he should refuse. For the player making the offer, the occupation of the x-field is still a possibly decisive speed move.

A game maneuver that forces the corner to be exchanged for a weak lineup of the opponent is the stoner trap (see Fig. Stoner trap ). The corner sacrifice is prepared by White bringing the main diagonal under control with move b7 . This is important because the stoner trap requires a second preparation move and the opponent is not allowed to occupy the corner immediately. If Black turns a stone in the main diagonal on the next move (e.g. to b3 ) and threatens to occupy corner a8 , White responds with the attack move c8 and threatens to occupy corner h8 . If Black takes the corner a8 , White answers with b8 and later follows h8 , which gives her seven stable stones. If Black wants to prevent White from moving to h8 with b8 , things get worse and White gets both corners and the entire edge with a8 and then h8 . A move other than a8 or b8 doesn't help either , because of White's threat to occupy corner h8 . However, extreme care should be taken when setting the stoner trap. If the moves cannot be carried out as calculated in advance, the sacrificed corner can be lost without compensation.

Othello World Championship

| year | place | World Champion | country | team | 2nd place | country | world champion | country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1977 | Tokyo | Hiroshi Inoue | Japan | N / A | Thomas Heiberg | Norway | ||

| 1977 * | Monte Carlo | Sylvain Perez | France | N / A | Michel Rengot (Blanchard) | France | ||

| 1978 | New York City | Hidenori Maruoka | Japan | N / A | Carol Jacobs | United States | ||

| 1979 | Rome | Hiroshi Inoue | Japan | N / A | Jonathan Cerf | United States | ||

| 1980 | London | Jonathan Cerf | United States | N / A | Takuya Mimura | Japan | ||

| 1981 | Brussels | Hidenori Maruoka | Japan | N / A | Brian Rose | United States | ||

| 1982 | Stockholm | Kunihiko Tanida | Japan | N / A | David Shaman | United States | ||

| 1983 | Paris | Ken'ichi Ishii | Japan | N / A | Imre Leader | Great Britain | ||

| 1984 | Melbourne | Paul Ralle | France | N / A | Ryoichi Taniguchi | Japan | ||

| 1985 | Athens | Masaki Takizawa | Japan | N / A | Paolo Ghirardato | Italy | ||

| 1986 | Tokyo | Hideshi Tamenori | Japan | N / A | Paul Ralle | France | ||

| 1987 | Milan | Ken'ichi Ishii | Japan | United States | Paul Ralle | France | ||

| 1988 | Paris | Hideshi Tamenori | Japan | Great Britain | Graham Brightwell | Great Britain | ||

| 1989 | Warsaw | Hideshi Tamenori | Japan | Great Britain | Graham Brightwell | Great Britain | ||

| 1990 | Stockholm | Hideshi Tamenori | Japan | France | Didier Piau | France | ||

| 1991 | New York City | Shigeru Kaneda | Japan | United States | Paul Ralle | France | ||

| 1992 | Barcelona | Marc tastes | France | Great Britain | David Shaman | Great Britain | ||

| 1993 | London | David Shaman | United States | United States | Emmanuel Caspard | France | ||

| 1994 | Paris | Masaki Takizawa | Japan | France | Karsten Feldborg | Denmark | ||

| 1995 | Melbourne | Hideshi Tamenori | Japan | United States | David Shaman | United States | ||

| 1996 | Tokyo | Takeshi Murakami | Japan | Great Britain | Stéphane Nicolet | France | ||

| 1997 | Athens | Makoto Suekuni | Japan | Great Britain | Graham Brightwell | Great Britain | ||

| 1998 | Barcelona | Takeshi Murakami | Japan | France | Emmanuel Caspard | France | ||

| 1999 | Milan | David Shaman | Netherlands | Japan | Tetsuya Nakajima | Japan | ||

| 2000 | Copenhagen | Takeshi Murakami | Japan | United States | Brian Rose | United States | ||

| 2001 | New York City | Brian Rose | United States | United States | Raphael Schreiber | United States | ||

| 2002 | Amsterdam | David Shaman | Netherlands | United States | Ben Seeley | United States | ||

| 2003 | Stockholm | Ben Seeley | United States | Japan | Makoto Suekuni | Japan | ||

| 2004 | London | Ben Seeley | United States | United States | Makoto Suekuni | Japan | ||

| 2005 | Reykjavík | Hideshi Tamenori | Japan | Japan | Kwangwook Lee | South Korea | Hisako Hoshi | Japan |

| 2006 | Mito | Hideshi Tamenori | Japan | Japan | Makoto Suekuni | Singapore | Toshimi Tsuji | Japan |

| 2007 | Athens | Kenta Tominaga | Japan | Japan | Stéphane Nicolet | France | Yukiko Tatsumi | Japan |

| 2008 | Oslo | Michele Borassi | Italy | Japan | Tamaki Miyaoka | Japan | Liya Ye | Germany |

| 2009 | Ghent | Yusuke Takanashi | Japan | Japan | Matthias Berg | Germany | Mei Urashima | Japan |

| 2010 | Rome | Yusuke Takanashi | Japan | Japan | Michele Borassi | Italy | Jiska Helmes | Netherlands |

| 2011 | Newark, NJ | Hiroki Nobukawa | Japan | Japan | Piyanat aunchule | Thailand | Jian Cai | United States |

| 2012 | Leeuwarden | Yusuke Takanashi | Japan | Japan | Kazuki Okamoto | Japan | Veronica Stenberg | Sweden |

| 2013 | Stockholm | Kazuki Okamoto | Japan | Japan | Piyanat aunchule | Thailand | Katie Wu | Finland |

| 2014 | Bangkok | Makoto Suekuni | Japan | Japan | Ben Seeley | United States | Joanna William | Australia |

| 2015 | Cambridge | Yusuke Takanashi | Japan | Japan | Makoto Suekuni | Japan | Yoko Sano | United States |

| 2016 | Mito | Piyanat aunchule | Thailand | Japan | Yan Song | China | Zhen Dong | China |

| 2017 | Ghent | Yusuke Takanashi | Japan | Japan | Akihiro Takahashi | Japan | Misa Sugawara | Japan |

| 2018 | Prague | Keisuke Fukuchi | Japan | Japan | Piyanat aunchule | Thailand | Misa Sugawara | Japan |

| 2019 | Tokyo | Akihiro Takahashi | Japan | Japan | Yusuke Takanashi | Japan | Joanna William | Australia |

* The rival World Championship in Monte Carlo is usually not considered official and is often referred to on official websites as the first European Championship.

Computer Othello

See also

- Ataxx , completely different rules and strategy, but almost the same board, the same pieces and the same goal.

literature

- Erwin Glonnegger : The game book: board and placement games from all over the world; Origin, rules and history . Drei-Magier-Verlag, Uehlfeld 1999. ISBN 3-9806792-0-9 .

- Michael Buro: Techniques for the evaluation of game situations using examples . Dissertation, University of Paderborn, 1994.

- Paul S. Rosenbloom: A world-championship-level Othello program . In: Artificial Intelligence . Vol. 19, No. 3, 1982, ISSN 0004-3702 , pp. 279-320.

- Kai-Fu Lee and Sanjoy Mahajan: The development of a world class Othello program . In: Artificial Intelligence . Vol. 43, No. 1, 1990, ISSN 0004-3702 , pp. 21-36.

Web links

- Othello Club Germany

- World Othello Federation (English)

- Reversi / Othello at the European Game Collectors Guild

- Othello in the board game database BoardGameGeek (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Martin Gardener: Mathematical puzzles . Springer Verlag, 2013, page 56. Retrieved May 27, 2020

- ↑ Vintage Othello and Reversi . retrowow.uk, accessed on May 27, 2020

- ↑ Trees van Seggelen: WOC 2014 Results. November 29, 2014, accessed May 5, 2015 .