Hans Fugger (weaver)

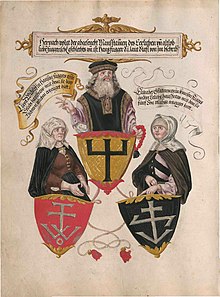

Hans Fugger (originally written Fucker , * in Graben ; † 1408/09 in Augsburg ) is the common progenitor of both lines of the Swabian merchant family Fugger : the Fugger from the deer and the Fugger from the lily . In the Fugger family history, he is considered to be the original generation.

Life

Hans Fugger was the son of the country weaver Johann "Hans" Fugger (or Fucker) and his wife Anna Maria, geb. Meißner († 1395) from Graben. His year of birth is unknown and is roughly estimated to be around 1350. Like his father, he became a master weaver and, through diligence, business acumen, luck and two advantageous marriages, he achieved prosperity and influence in Augsburg, thus laying the foundation for the family's financial and social advancement.

He moved to Augsburg in 1367 and was noted in the Augsburg tax book of that year with “Fucker advenit” ( Latin for “Fugger has arrived”). The wealth tax that he paid suggests a certain amount of wealth as soon as he arrives. In 1367 (according to other sources not until 1370) he married the weaver's daughter Klara Widolf († 1378), whose father Oswald Widolf became the weavers' guild master in 1371. With this marriage he became a citizen of Augsburg, a member of the weavers' guild and recipient of an impressive dowry .

After Klara's death, no later than 1380 (according to another source about 1382), he married Elisabeth Gfattermann († 1436) as a second marriage. His second father-in-law also became the weavers' guild master in 1386; he was also rich and a councilor. In the same year, Hans Fugger was elected to the committee of twelve of the weavers' guild, i.e. its extended board. He expanded his business into the textile trade and thus laid the basis for the later Fugger merchant dynasty. He benefited from the then fustian boom and acted late 14th century as "Weber publisher " with linen , which he bought up in Bavarian weavers and sold, while as far as Italy exported.

Finally, Hans Fugger himself became the chairman of the local weavers' guild. In 1397 he moved from the weavers 'quarter in the Frauenvorstadt, where poor craftsman families lived, to the upper town of the affluent, where he was able to buy a house on Reichsstrasse opposite the weavers' guild house (near St. Moritz ). He now belonged to the richest percent of the city and could compete financially with members of long-established patrician families .

family

As far as is known, there were three children from Hans Fugger's first marriage and four children from his second marriage, some of whose life dates are unknown. The sons Andreas Fugger (1394 / 95–1457 / 58) and Jakob Fugger the Elder (after 1398–1469) come from the second marriage .

Hans Fugger had a brother Ulrich (Ulin) Fugger († 1394), who was also a weaver and who also moved from Graben to Augsburg in 1368. This is not to be confused with Ulrich Fugger the elder , who was Hans Fugger's grandson. The descendants of Hans Fugger's brother Ulrich can be traced back to Augsburg for about 50 years, but were not significant for the history of the city.

Development after his death

Hans Fugger died in 1408 or 1409. His widow Elisabeth continued the weaving and textile trade until her death in 1436, continuously increasing the company's assets and building up a copper monopoly. She let her sons Andreas and Jakob learn the goldsmith's trade as apprentices and she taught them the weaving trade and the cloth trade herself. The two brothers form the "second generation" of the Fuggers. They worked together in business, as can be seen from the joint tax assessment.

Andreas Fugger was a member of the Augsburg City Council and had a great influence. In 1448 the brothers jointly owned the fifth largest fortune in the city, but eventually they went their separate ways. In the tax book of 1455 they were assessed separately for the first time.

Andreas Fugger died soon after the company split. His sons continued to run his company and in 1462 they received a coat of arms with the coat of arms of a jumping deer. Therefore this branch of the family is called " Fugger vom Reh ". Their company was the late 15th century because of a risky loan, they Archduke Maximilian I had given, insolvent. Maximilian refused to repay, and the security provided proved worthless. After the bankruptcy only a few descendants of this branch gained validity.

Jakob Fugger's family branch, however, continued to flourish. He received a coat of arms with the coat of arms image of two lilies , therefore this branch is called " Fugger of the lily ". After Jakob Fugger's death in 1469, his widow Barbara and then his sons continued to run the father's company. They made it one of the largest and richest trading houses in Europe. His son Jakob Fugger was nicknamed “the rich”. At the beginning of the 16th century the family began to rise to the nobility .

House brands or coats of arms

The trident was Hans Fugger's house brand , which he ran in Augsburg in 1370. Later it was used as a trademark and as the family coat of arms of the Fugger family.

literature

- Mark Häberlein : The Fugger: History of an Augsburg family (1367-1650) . W. Kohlhammer Verlag, 2006, ISBN 978-3-17-018472-5 ( books.google.de ).

- Martha Schad : The women of the house of Fugger von der Lilie (15th-17th centuries): Augsburg, Ortenburg, Trient . Mohr Siebeck, 1989, ISBN 978-3-16-545478-9 ( books.google.de ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Max Jansen: The beginnings of the Fugger . BoD - Books on Demand, 2013, ISBN 978-3-95580-098-7 , pp. 10 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ A b Family tree of Hans Fugger. In: geneanet.org. Geneanet, accessed March 20, 2020 .

- ↑ Nadja Ameziane: On the way up. The efforts of the Fugger lines for advancement into the nobility . GRIN Verlag, 2018, ISBN 978-3-668-69342-5 , pp. 4 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Mark Häberlein: The Fugger: History of an Augsburg family (1367-1650) . W. Kohlhammer Verlag, 2006, ISBN 978-3-17-018472-5 , pp. 17 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ a b c Martha Schad: The women of the house of Fugger von der Lilie (15th-17th centuries): Augsburg, Ortenburg, Trient . Mohr Siebeck, 1989, ISBN 978-3-16-545478-9 , pp. 9 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ a b Mark Häberlein: The Fugger: History of an Augsburger Family (1367-1650) . W. Kohlhammer Verlag, 2006, ISBN 978-3-17-018472-5 , pp. 18 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Dagmar Klose: Freedom in the Middle Ages using the example of the city . Universitätsverlag Potsdam, 2009, ISBN 978-3-940793-95-9 , p. 119 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Mark Häberlein: The Fugger: History of an Augsburg family (1367-1650) . W. Kohlhammer Verlag, 2006, ISBN 978-3-17-018472-5 , pp. 18 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Dagmar Klose: Freedom in the Middle Ages using the example of the city . Universitätsverlag Potsdam, 2009, ISBN 978-3-940793-95-9 , p. 120 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ Martin Kluger: Fugger - Italy. Business, Weddings, Knowledge and Art. Story of a fruitful relationship. Context, Augsburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-939645-27-6 .

- ↑ Martha Schad: The women of the house of Fugger from the lily (15th-17th century): Augsburg, Ortenburg, Trient . Mohr Siebeck, 1989, ISBN 978-3-16-545478-9 , pp. 10 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Mark Häberlein: The Fugger: History of an Augsburg family (1367-1650) . W. Kohlhammer Verlag, 2006, ISBN 978-3-17-018472-5 , pp. 19 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Max Jansen: The beginnings of the Fugger . BoD - Books on Demand, 2011, ISBN 978-3-86403-024-6 , pp. 168 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ a b Mark Häberlein: The Fugger: History of an Augsburger Family (1367-1650) . W. Kohlhammer Verlag, 2006, ISBN 978-3-17-018472-5 , pp. 20 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Mark Häberlein: The Fugger: History of an Augsburg family (1367-1650) . W. Kohlhammer Verlag, 2006, ISBN 978-3-17-018472-5 , pp. 31 ( books.google.de ).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Fugger, Hans |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Fucker, Hans |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Ancestor of the Fugger from the deer and the Fugger from the lily |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 14th Century |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | dig |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1408 or 1409 |

| Place of death | augsburg |