Ignorance as state protection?

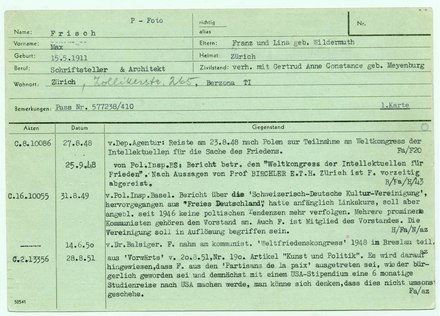

Ignorance as state protection? is an unfinished book manuscript of the Swiss writer Max Frisch in 1990. Frisch worked in the so-called Fichenaffäre on, around 900,000 under which Swiss authorities Fichen docked to numerous domestic and foreign persons wanted for monitoring documented. From 1948 on, Frisch was also monitored by the Swiss state for 42 years. When he got access to his fiche in 1990, he commented on it under the title Ignorance as State Protection? The project was not completed because of the advanced illness of the writer. It was not until 2015 that Frisch's notes appeared together with a facsimile of the fiche and detailed comments by the editors David Gugerli and Hannes Mangold in Suhrkamp Verlag .

content

Frisch already shows numerous inaccuracies and errors in the personal data on the cover sheet of the fiche. His middle name seems just as unknown to the state security as his children. Addresses and street names are shortened or incorrectly given, many long-term places of residence are not listed. Frisch commented that it was apparently a sufficient qualification for a state security officer to write off addresses incorrectly. The first entry dates from August 1948, when Frisch attended a peace congress in Poland . The name of the informant is blackened in the fiche, which raises the question of whether it was the Swiss ambassador or his companion François Bondy - in fact, according to the unbranded fiche, the information came from Linus Birchler , professor at ETH Zurich , and the Quelle was a publicly available newspaper article. Later entries are partly completely blacked out. Frisch comments on this with the remark that the defaced content is as certain as any state secret.

The legible entries, on the other hand, are often banal and do not reveal what the state security found remarkable about the information. When the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade was awarded in 1976, the word “peace” may already seem suspicious. Again and again the monitors betray their complete ignorance of the writer's works. They use an article in the free newspaper Silva Revue as evidence of statements that anyone could have read in Frisch's publications. The last entry dates from January 1990, when a GDR ambassador contacted the Swiss writer. The time of the entry proves Frisch that the fiche continued undeterred even after it became known and public promises to be discontinued.

Disappointed by the numerous gaps in his fiche, Frisch finally draws up a long list of events from his life that are not noted in the fiche. In a final comment, he states that none of the entries in his fiche document any unconstitutional act. Obviously, the surveillance is not about prosecuting criminals, but about observing all persons whose statements differ from the prevailing opinion, especially that of the Free Democratic Party . This is enough to be seen as an enemy of the state and a traitor . Walter Gut, the Fichen delegate, has taken on a Herculean task. But he is apparently primarily concerned with blackening the files and delaying their inspection as a result. Only an open handling of the fiche could save the Federal Prosecutor's Office from the reputation "as a Feme -Institute brimming with ignorance, narrow-mindedness over four decades, provincialism and impertinence".

shape

For the processing of his fiche, Frisch used the technique of collage , which he often used in his later work, particularly striking in the story Man appears in the Holocene , where notes, lexicon entries and illustrations are mounted in the text. He cut up his fiche into small pieces, stuck them on a piece of paper and used the typewriter to comment on them in the spaces between them. In the book edition, the fiche and comments are set in different fonts. A facsimile of the original fiche is also attached. David Gugerli and Hannes Mangold emphasize in their foreword that Frisch's typescript follows the same mechanical laws in its methodology that have determined the state security's index card system. Frisch's text is thus also a contemporary document of a still completely analog information processing, administration and monitoring.

interpretation

“Ignorance, narrow-mindedness, provincialism and impertinence - Max Frisch didn’t skimp on allegations of the Swiss State Security”, judge David Gugerli and Hannes Mangold in the afterword of the book edition. It is not only the fact of the surveillance that arouses the incurable illness of the 79-year-old and spurs him on to one last literary work, but also the banality of the recorded facts. It is precisely the lack of a concrete charge, the non-existent offense that makes those under surveillance unrest. Every political act that is in contradiction to the bourgeois parliamentary majority becomes, through its inclusion in the fiche, an act that is suspicious of state security. Frisch wonders what to do with these lists in a potential "emergency" when the federal police have to arrest every deviant. The obvious dilettantism of the authorities is not something that freshly calms and reconciles the subjects, but rather a cause for shame. He worries that Switzerland is only perceived internationally as a “village idiot”. For David Gugerli, it is a primal fear of the Swiss to make a fool of themselves when trying to play along with the “big ones”. As an “upright confederate”, Frisch too would like a state that he “could take seriously, even as an opponent of the citizen.”

The question of identity , role , image of others and of self is a central theme in Max Frisch's work. In the essay Our greed for stories from 1960, he described: “Every person invents a story that he then believes to be his life, often at huge sacrifices, or a series of stories that can be substantiated with place names and dates, like this that their reality cannot be doubted. ”By looking into his fiche, the author must learn that the state security has tinkered with a careless, flawed, distorted picture of himself for many years. Frisch's typescript is thus an attempt to regain authority over one's own biography. Like his fictional character Stiller , Frisch fights against a prefabricated image, but he no longer makes use of literary fiction, instead resorting to the techniques of the authorities, for example by quoting a parade document of the subjects' control with his passport to prove his middle name. Unlike the testimony of witnesses in the trial against Felix Schaad in Bluebeard , the entries in the fiche do not lead to any dramatic exacerbation. The same banal and tiresome details are just lined up for pages, against the ignorance of which Frisch's defense is just as futile as his listing of missing entries, which obviously occupied the author for days.

The question mark with which Frisch used the title of his typescript Ignoranz als Staatsschutz? decides to refer to Gugerli and Mangold as a symbol typical of the author Max Frisch. Frisch already marked earlier works of his exploration of his home country with this symbol, so Switzerland as home? , his speech on the presentation of the Great Schiller Prize 1974, and the late play Switzerland without an Army? from 1989. According to Gugerli and Mangold, Frisch also used the question mark to “measure the blind spot in his last text”. It can be understood as a sign of the sarcasm of a disappointed citizen who realizes at the end of his typescript that his appeals to an open approach to the fiche will meet with the same ignorance as his defense of himself. The title also generally poses the question, how ignorance and state security relate to one another, whether they are conditional or whether ignorance makes any effective protection impossible. In any case, Gugerli and Mangold ask whether state protection in a democratic system "is always and per se an ignorant undertaking, because state security officers basically cannot know what needs to be preserved and what dangers threaten the state?"

expenditure

- Ignorance as state protection? Edited by David Gugerli and Hannes Mangold. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-518-42490-2

-

The F. - Max Frisch file on his fiche and Swiss State Security , in: NZZ -Geschichte , Zurich, No. 3, October 2015, p. 23 ff. ( Abridged preprint of the book), with the contributions:

- Max Frisch comments on his fiche. (Excerpts from facsimiles, p. 24 f.)

- David Gugerli, Hannes Mangold: Ignorance as state security? Why Max Frisch got angry while reading his fiche. (P. 37 f.)

- Julian Schütt: Frisch and the NZZ : a mutual misunderstanding. (P. 41 f.)

- State mistrust. Why did the Swiss state monitor its citizens? Conversation between the federal data protection officer Hanspeter Thür and Peter Huber, the former head of the federal police, moderated by Martin Beglinger and Peer Teuwsen. (Pp. 47–57)

Web links

- State security ahoy! . In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung from October 3, 2015.

- Andreas Bernard: What his supervisors missed . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung from October 6, 2015.

- Andreas Tobler: "A document of ignorance, narrow-mindedness, provinciality" . In: Tages-Anzeiger from October 6, 2015.

- Andreas Tobler: The state security files that Max Frisch was not allowed to see . In: Tages-Anzeiger from October 8, 2016.

- "Frisch was a potential traitor for the state security . " In: SRF from October 6, 2015.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Andreas Tobler: The state security files that Max Frisch was not allowed to see . In: Tages-Anzeiger from October 8, 2016.

- ↑ Max Frisch: Ignorance as state security? (2015), p. 71.

- ↑ David Gugerli, Hannes Mangold: Introduction . In: Ignorance as State Protection? (2015), pp. 9-10, 25.

- ↑ David Gugerli, Hannes Mangold: Afterword . In: Ignorance as State Protection? (2015), p. 111.

- ↑ David Gugerli, Hannes Mangold: Afterword . In: Ignorance as State Protection? (2015), pp. 111, 114–115.

- ↑ Max Frisch: Ignorance as state security? (2015), p. 59.

- ↑ Andreas Bernard: What escaped his supervisors . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung from October 6, 2015.

- ↑ Max Frisch: Our greed for stories . In: Collected works in chronological order. Fourth volume . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-518-06533-5 , p. 263.

- ↑ David Gugerli, Hannes Mangold: Afterword . In: Ignorance as State Protection? (2015), pp. 113–116, 122, 126.

- ↑ David Gugerli, Hannes Mangold: Introduction . In: Ignorance as State Protection? (2015), p. 25.

- ↑ David Gugerli, Hannes Mangold: Afterword . In: Ignorance as State Protection? (2015), pp. 116–117.