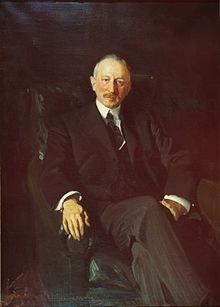

Jacques Seligmann

Jacques Seligmann (born September 18, 1858 in Frankfurt am Main , † October 31, 1923 in Paris ) was a French art dealer .

Life

Jacques Seligmann was born the son of a grain dealer in Frankfurt am Main. In 1874 he moved to Paris and took French citizenship. He initially worked as an assistant to the auctioneer Paul Chevallier and the expert in medieval art Charles Mannheim (1833–1910). In 1880 Seligmann opened his own shop on Rue des Mathurins. Through Mannheim he came into contact with the entrepreneur and collector Baron Edmond de Rothschild , who was one of his first customers. In 1900, together with his brothers Arnold and Simon, he founded the company Jacques Seligmann & Cie . In the same year the shop moved to the noble Place Vendôme , where it received customers on four floors.

Seligmann traveled regularly to Vienna, Rome, Madrid, London and Saint Petersburg to purchase new art objects, meet customers and visit museums. His clientele included members of the Russian Stroganov family and the art-loving British politician and supporter of the London National Gallery, Sir Philip Sassoon.

In 1904 he opened a branch in New York City and has worked there for several weeks a year since then. His American clients included banker John Pierpont Morgan , department store owner Benjamin Altman , newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst , railroad entrepreneur Henry Walters , wine merchant George Kessler , banker Seventh President of the Metropolitan Museum of Art George Blumenthal, and real estate heir Joseph E. Widener , whose collection later received the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

At the beginning, Seligmann mainly dealt with antiques, including porcelain, enamel work, ivory objects and sculptures. Tapestries and especially French furniture from the 18th century were particularly in demand. In 1902 JP Morgan acquired an exquisite gilded silver goblet from the possession of Baron Albert von Oppenheim from Cologne . There was also a copper-gilded ciborium from Klosterneuburg Abbey . In 1908 JP Morgan also bought a silver tabernacle from the collection of Count Arco-Zinneberg in Munich. The next year, a golden, jeweled book cover with the coat of arms of Philip II of Spain followed from Vienna or Augsburg .

In 1909, Seligmann acquired part of Sir Richard Wallace 's renowned collection for two million dollars . This included sculptures, furniture, carpets and porcelain. In the same year Seligmann acquired the city palace Hôtel de Monaco near the Esplanade des Invalides and received his most important customers here. After a dispute with his brother Arnold, he continued the business on Place Vendôme under the name Arnold Seligmann & Cie , while Jacques maintained international connections and opened a new Paris office in 1912 at 9 Rue de la Paix . In New York in 1914 he moved into a new office and gallery on New York's Fifth Avenue and 55th Street.

After the outbreak of war, the galleries were closed in autumn 1914 and the Hôtel de Monaco was given to the Red Cross. Seligmann continued the art trade with the United States and, for example, transported paintings to New York on board a neutral Spanish ship. With this foreign exchange income he helped to reduce the gold outflow in France during the war. "

From Philippe Berthelot , State Secretary in the French Foreign Ministry, Seligmann received an order to inventory the large holdings of Habsburg tapestries in Vienna in order to later sell them and thus cover possible reparations payments to France. The art dealer managed to dissuade his counterpart from the plan of mass sales of the carpets. Only a few paintings from Austrian ownership were handed over to Italy.

In 1920 his son Germain became head of the company's New York office. Seligmann died in Paris in October 1923. In its obituary, the London Times praised that Seligmann's best quality was his "fearless honesty" (meaning: fearless honesty ). Seligmann's correspondence and handwritten working documents are kept in the Archives of American Arts.

Web links

- Address book Frankfurt am Main, 1870, p. 302

- Germain Seligman, Merchants of Art, 1800-1960, eighty years of professional collecting, New York 1962

- Charles Bernard, Amédée Peyroux (et al.), La Grimace: satirique, politique, littéraire, théâtrale, Paris April 29, 1917

- Entry on Jacques Seligmann in the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- The Diaspora, February 8, 1924. Notice of death of Jacques Seligmann in The Hebrew Standard of Australasia (Sydney, NSW: 1895-1953), p. 17th

Individual evidence

- ↑ Address book Frankfurt am Main, 1870, p. 302 http://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/periodika/periodical/pageview/8696113

- ↑ Germain Seligman, Merchants of Art, 1800-1960, eighty years of professional collecting, New York 1962 ( [1] )

- ↑ Germain Seligman, Merchants of Art, 1800-1960, eighty years of professional collecting, New York 1962, p. 92 https://archive.org/stream/merchantsofart1800seli#page/92/mode/1up

- ↑ For the history of the Wallace Collection, see www.wallacecollection.org ( Memento of the original from September 17, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Germain Seligman, Merchants of Art, 1800-1960, eighty years of professional collecting, New York 1962, p. 110

- ^ Germain Seligman, Merchants of Art, 1800-1960, eighty years of professional collecting, New York 1962, p. 113

- ^ Adrien Hébrard (Ed.): Le Temps (Paris. 1861) - 82 années disponibles - Gallica . Paris November 2, 1923 ( bnf.fr [accessed September 17, 2017]).

- ^ The Diaspora, February 8, 1924. The Hebrew Standard of Australasia (Sydney, NSW: 1895-1953), p. 16. Retrieved September 16, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article129360209

- ↑ Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/search?edan_q=jacques+seligmann&op=Search

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Seligmann, Jacques |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French art dealer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 18, 1858 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Frankfurt am Main |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 31, 1923 |

| Place of death | new York |