John Guest

John Gast (born December 21, 1842 in Berlin , † July 26, 1896 in Brooklyn ) was an American painter and lithographer .

Life

According to information from his passport issued on July 23, 1867, his father Leopold Gast was also a lithographer and moved with his family to the United States when John was six years old. While Leopold can be traced as an artist in St. Louis , Missouri , John worked most of his life in Brooklyn , New York, where he is recorded in the records of the United States Census in 1875, 1880 and 1890 .

Thanks to the biography that Leopold Gast wrote in 1894 and 1897, many periods in the life of his son John (alias Hans) are well documented.

Childhood and emigration to America

John was baptized as the son of Leopold Heinrich Gast and his wife Bertha Volckmann on January 22, 1843 in Berlin in the (Bohemian) Bethlehem Church by Pastor Gossner under the name "Johannes". He was called "Hans" by his family. Berlin was just a stopover in my father's professional life. Just two years after John's birth, the family moved to Halle an der Saale , where the father started his own business as a lithographer. It was there that the plans to emigrate to America also matured. In the revolutionary year of 1848 , the Gast family embarked for New Orleans in Bremen . The family settled in St. Louis, Missouri. The father Leopold founded a lithographic company together with his brother August, but August soon withdrew from it. Hans learned to play the piano, which he mastered very well, and showed a talent for drawing and painting at an early age. The father encouraged this talent and placed great hopes in Hans. He would later work in the company and take over.

Studies in Germany

In 1860, at the age of 18, he accompanied his father on a visit to Germany. Leopold returned to St. Louis, Hans stayed in Germany to study at the Berlin Art Academy. His professors included Ferdinand Bellermann and Theodor Hosemann , who both also looked after Hans privately when he had no support from home because of the American Civil War (1861-1865). In return, Hans gave English lessons. At home in St. Louis, the parents had great financial worries, the older son Paul was an officer in the war, on the one hand there was a lack of help, on the other hand there was a risk that Hans would be drafted when he returned home. It was only when his father Leopold became seriously ill that Hans was brought back to St. Louis in September 1864 after an absence of four and a half years.

Teacher in Washington, Missouri

Hans was torn between being grateful and fulfilling his duty to his father and his desire to become a painter. Since the order situation in St. Louis was still bad, the father agreed that Hans earned money as a drawing teacher at the university and at the Mary Institute in Washington, Missouri. He also still lacked lithographic skills. He was to acquire this on another trip to Europe in Paris.

Studies in Paris

On June 24, 1867, he traveled to New York via Boston, where he was introduced to the New York, or Brooklyn, society. On July 25, 1867, he traveled on to Paris . Life in Paris was initially sobering for Hans, he felt strange. Unlike in Germany, where he could rely on his father's contacts, he had to make ends meet here. But he soon found work for a chromo (oil color printing) company, the Alsatian Thürwanger brothers. In spite of all this, he did not feel at home, complained in letters that he was homesick and asked his father to be allowed to continue his studies at least in Berlin. Only when he was able to get in touch with the Winter family (old friends of his father) in Paris through the recommendation of his father and offered him a social life, did he feel at home and enjoy the opportunity to continue his education.

Establishing your own company

In June 1868 his father asked Hans to return from Paris. After the death of his business partner, he was unable to continue running the lithography company on his own, and the heirs of the former partner had to be paid off. Now the father put all his hopes in Hans, to whom he handed over the company. In order to secure the financing, a new partner had to be found. Hans offered his uncle August a partnership, Leopold Gast & Son became John Gast & Co. Hans Gast, however, still lacked the necessary knowledge to work as a lithographer. His studies in Berlin and Paris had made him an oil printing specialist, but not a lithographer.

On September 30, 1869, Hans (John) traveled from St. Louis to NY to do a large chromolithography oil color print for the artist Thompson, and other well-paid jobs followed. At the end of 1869 Hans returned home surprisingly, he suffered from severe joint and limb rheumatism, after this was overcome, he sold his share of the business to his uncle August. Leopold was very disappointed in his son, in whom he had placed such high hopes. He described him as haughty, frivolous, and ungrateful.

Wedding and life in Brooklyn

In 1870 John got engaged in Brooklyn to the widow Augusta Marie Catharine Stohlmann * June 27, 1842. They probably married in 1870. Auguste brought a son into the marriage. Although Leopold valued his daughter-in-law's family very much, and even liked them after meeting them for the first time, he refused any contact with his son and his wife Auguste for four years. John Leopold, the son of John and Auguste born in 1876, died on July 3, 1877.

The daughter Augusta Marie Catharine (Marie Louise) was born on August 10, 1879 in Brooklyn. John and his wife lived in seclusion at 297 Adelphi Street in Brooklyn. John Gast died in June 1896 at the age of 54.

plant

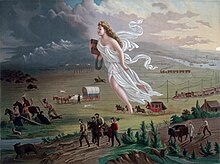

Although the majority of Gast's artistic work consists of lithographs, he achieved international fame primarily through a painting. In 1872 he made on behalf of the publisher George Crofutt an oil painting in which he initially called Westward Ho / Manifest Destiny was that but now as American Progress ( American Progress ) is known. The image symbolically exaggerates the settlement of the American West in allegory to Manifest Destiny as a civilizing-religious task of the settlers.

Corfutt, who edited a number of travel guides, not only included a print of the painting in one of his books, but also made an enlarged chromolithograph of it for his subscribers. As a result, the print version of the painting quickly became the best-known visualization of the Manifesto Destiny Christopher Schmidt called the painting “a key work of national self-perception” in the USA.

Nowadays the picture statements are received rather critically. The historian Amy S. Greenberg calls the portrayal of the settlers "complacent and self-righteous", the sociologist Wulf D. Hund sees it as "cultural chauvinism". In particular, the portrayal of the North American Indians as displaced by civilization gives cause for criticism.

In 2000, the work was part of a selection of 120 paintings and sculptures that were part of the exhibition The American West: Out of Myth, Into Reality at the Mississippi Museum of Art in Jackson, the Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago, Illinois and were shown at the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio.

Web links

- Short biography and information about the work on askart.com

- Essay by historian Martha A. Sandweiss on guest and the painting "American Progress"

- Painting by Gast in the Department of Drawings and Prints at the Library of Congress

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Biographical information. In: askart.com. Retrieved November 11, 2016 .

- ^ Leopold Gast: A guest on earth, and his pilgrimage through the old and new world . In: Bertelsmann (Ed.): Biography . tape 1 + 2 . C. Bertelsmann, Gütersloh 1894, OCLC 162989860 .

- ↑ Obituary in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle June 26, 1896

- ^ Hans-Dieter Gelfert : Typically American. How Americans became what they are, third edition, Munich: CH Beck 2006, p. 14

- ↑ Martha A. Sandweiss, John Gast, American Progress, 1872 , ( online )

- ↑ “perhaps the best-known nineteenth century image of Manifest Destiny”, Shane Mountjoy: Manifest destiny: westward Expansion , New York: Chelsea House 2009, p. 19

- ↑ “Perhaps the best-known image of nineteenth-century American concept of Manifest Destiny”, Amy S. Greenberg: Manifest manhood and the antebellum American empire , New York: Cambridge University Press 2005, p. 1

- ↑ Süddeutsche Zeitung No. 49, February 28/1. March 2015, p. 20.

- ^ Amy S. Greenberg: Manifest manhood , p. 1

- ^ Wulf D. Hund : Racism: the social construction of natural inequality , Münster: Verlag Westfälisches Dampfboot 1999, p. 48

- ↑ "The Indian becomes the (temporally) lagging behind, the underdeveloped": Henning Eichberg : Disconnection: Reflecting on the new German question , Bublies 1987, p. 67

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Guest, john |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American painter and lithographer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 21, 1842 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Berlin |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 26, 1896 |

| Place of death | Brooklyn |