Gospel of Judas

The Gospel of Judas , abbreviated EvJud , is an apocryphal script that was probably written in a Gnostic sect in the middle of the 2nd century AD . The script does not come from Judas , but is a pseudepigraphic script. It essentially consists of conversations between Jesus and the disciples or Jesus and Judas on several days shortly before the Passion .

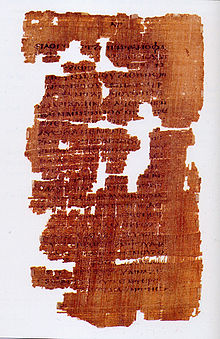

It was first mentioned and described by Irenaeus of Lyon around 180 AD. It was considered lost until the 1970s. In 1976 a papyrus from the 4th century, the so-called Codex Tchacos, was discovered, which contains the Gospel of Judas in Coptic translation. This manuscript was first published by Rodolphe Kasser in April 2006 . The Coptic text is considered to be a later version of the Gospel of Judas originally written in Greek.

Historically, Scripture does not provide any information about Jesus or Judas, but only about their reception in early Christianity.

History of the work and the text witnesses

According to the religious historian Gregor Wurst, the script was created around 160 AD, much later than the biblical Gospels. It has been speculated that an underlying Greek text could come from the 1st century. Most researchers assume that it originated in the middle of the 2nd century.

Irenaeus of Lyon dealt with the book around 180 AD and distanced himself from the statement that Jesus had asked Judas to betray him in order to be freed from his physical shell and to be able to fully fulfill his task as Messiah .

The text known today is only available in a text witness in a Coptic translation, as part of the Codex Tchacos, which was found in Middle Egypt near the city of al-Minya in 1976 , stolen soon after and reappeared in 1983. This is a defective and therefore incomplete papyrus - Codex from the 4th century. Due to improper storage, the codex had disintegrated into hundreds of small fragments. For the reconstruction, each fragment was photographed on both sides and put together on the computer by Gregor Wurst ( University of Augsburg ) and his colleagues. In the course of three years, almost 90 percent of the text could be reconstructed. The manuscript, translated under the direction of Professor Rodolphe Kasser from Geneva , was published in 2006. In 2007 a critical edition of the four texts of the Codex Tchacos was published.

In 2009, a majority of the missing fragments, which were hiding in the USA, were released by a court order. They are now to be reunited and evaluated in Europe with the already known parts of the Codex. After the translation and restoration of the script, the foundation wants the code to be handed over to the Egyptian state for the attention of the Coptic Museum in Cairo .

Reception and assessment

On April 9, 2006, National Geographic magazine published the results of the surveys worldwide on its television channels as part of a two-hour documentary special .

According to Thomas Söding , the document does not contain any previously unknown words of Jesus that could be considered authentic. The EvJud reflects the view of an oppositional Christian group from the 2nd century, which split off from the majority church and above all did not recognize its ministers; these are represented in EvJud by the twelve apostles .

content

The reliability and quality of the first translation by Kasser u. a. is controversial.

Content (according to Kasser et al.)

Kasser understands the Gospel as a 'Cainite' counter-Bible. The Cainites were a splinter Gnostic sect who worshiped Cain and Judas in the 2nd century . Irenaeus of Lyon wrote: "They created a fictional story that they call the Gospel of Judas". The core message of the Gospel of Judas is that Judas was Jesus' best friend and possessed more knowledge (gnosis) than all other disciples. Jesus therefore commissioned Judas to betray him for the sake of salvation. Because through the betrayal, Jesus was able to leave his bodily shell and return to the true divine kingdom. Judas then asked Jesus what his reward was for the betrayal, and Jesus answered him very openly that the whole world would hate and condemn him forever, but that he would also enter the true divine kingdom as an enlightened one. Here, however, the true God is not the 'Jewish God' whom the other disciples worship, but a far superior being. The Jewish (and Orthodox-Christian) God is only a subordinate deity in this Gospel with a defective and malicious creation, which has to be overcome through true knowledge. Forgiveness of sins through Jesus' death and bodily resurrection are completely incompatible with the theology laid out in this Gospel. An essential theological element of the text is the revelation of a complete myth of the origin of the world, with which the distinction between the enlightened (the Gnostics) and the non-enlightened as well as the rejection of early Christian orthodoxy is justified. The text, which is only preserved here in very fragments, ends with a prophecy from Jesus, which conjures up the downfall of the Old Testament God and all of his inferior creation. This downfall of everything earthly is likely triggered by the betrayal of Judas and the physical death of Jesus.

Content (according to DeConick et al.)

A more recent translation by April D. DeConick states that Judas is by no means described in the Gospel of Judas as a friend of Jesus, but in truth as a demon . The interpretation by National Geographic is based on translation errors, some of which are dramatic. They lead to Judas being presented as a radiant personality, contrary to the meaning of the text, as the closest friend of Jesus and the only one who understands him: as a “spirit” and not as a “demon”; at a crucial point the Greek “daimon” (δαίμων) is translated as “spirit”. According to Hartenstein it is at least not the case that the EvJud simply rehabilitates Judas as a traitor: “Jesus announces this deed, he does not demand it and there are some arguments in favor of a negative assessment. In addition, Judas is also imperfect and is excluded from achieving total salvation. "

literature

- Rodolphe Kasser , Gregor Wurst: The Gospel of Judas together with the Letter of Peter to Philip, James, and a Book of Allogenes from Codex Tchacos. Critical Edition. National Geographic Society, Washington 2007, ISBN 978-1-4262-0191-2 .

- Rodolphe Kasser, Gregor Wurst, Marvin Meyer, Francois Godard: The Gospel of Judas. Second edition. National Geographic Society, Washington 2008, ISBN 978-1-4262-0048-9 .

- Rodolphe Kasser, Marvin Meyer, Gregor Wurst (eds.): The Gospel of Judas from the Codex Tchacos , National Geographic , Washington DC, White Star Vlg. (German edition) Wiesbaden 2006, ISBN 3-939128-60-0 .

- Herbert Krosney: The Lost Gospel. White Star, Wiesbaden 2006, ISBN 3-939128-61-9 .

- James M. Robinson: The Secrets of Judas: The Story of the Misunderstood Disciple and His Lost Gospel. Harper, San Francisco 2006, ISBN 0-06-117063-1 .

- The Gospel of Judas. German translation from Coptic. In: Uwe-Karsten Plisch: What is not in the Bible. Apocryphal writings of early Christianity. German Biblical Society, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-438-06036-1 , pp. 165–177. Also contained in: Scriptures of early Christianity. Apocryphal Gospels, explained by Uwe-Karsten Plisch; Apostolic Fathers, explained by Klaus-Michael Bull. German Bible Society, Stuttgart 2008 (CD-ROM), ISBN 978-3-438-02078-9 .

- Elaine Pagels , Karen L. King: The Gospel of the Traitor. Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-57095-7 .

- April D. DeConick: The Thirteenth Apostle: What the Gospel of Judas Really Says. Continuum, London / New York 2007, ISBN 978-0-8264-9964-6 .

- Friedrich Haller: The Judas Gospel. Friedrich Haller Verlag, Bonn 2012, ISBN 978-3-934917-33-0 .

Online texts

- Gospel of Jude in Coptic language (original text) ( PDF ; 218 kB)

- The Gospel of Judas , English translation by Rodolphe Kasser, Marvin Meyer and Gregor Wurst ( PDF ; 76 kB)

- The Gospel according to Judas Iscariot , German translation by Bernhard Siebert based on the English translation by R. Kasser et al. (PDF; 97 kB)

- CHERIX, P., Évangile de Judas , 2007–2012, sur Coptica.ch - texte, index et traduction française

Web links

- Judith Hartenstein: Gospel according to Judas. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- Hermann Detering: Judas and the "Judas Gospel", Berlin 2005

- “Judas Gospel” - betrayal as God's will, n-tv, April 6, 2006

- L 'évangile de Judas ( Memento of March 4, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- The National Geographic containing info on the Gospel of Judas, English

- Gospel of Judas: authentic fraud - extensive presentation, English

- ZDF: Secret Files of Jesus: The "Gospels of Heretics" - The dispute over the "correct" faith escalates

- ZDF Mediathek: Secret Files of Jesus: The "Gospels of Heretics" - The dispute about the "correct" faith escalates

References and comments

- ↑ Irenäus: "Against the heresies" (Adversus haereses), I 31,1, Brox p. 257.

- ↑ a b c Judith Hartenstein: Gospel according to Judas. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- ↑ See e.g. Bra-Ch. Puech, Beate Blatz: New Testament Apocrypha. Vol. 1, p. 387.

- ↑ A radiocarbon dating (Timothy Jull, University of Arizona ) provided a period between 3rd and 4th century for the development of the manuscript.

- ^ Mathias Schreiber, Matthias Schulz: The testament of the sectarians . In: Der Spiegel . No. 16 , 2009, p. 110-121 ( online - 11 April 2009 ).

- ↑ On the history of the publication R. Kasser / G. Sausage / M. Meyer 2006, pp. 47-76; critical view in James M. Robinson, pp. 17-119.

- ↑ Old script: Whirl around "Judas Gospel" In: Spiegel Online . April 6, 2006, accessed June 9, 2018 .

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/01/opinion/01deconink.html

- ↑ breaking news from san antonio ( Memento of January 8, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ April D. DeConick: The Thirteenth Apostle: What the Gospel of Judas Really Says. London / New York 2007, especially pp. 109–113.