Chortitza colony

The colony Chortitza ( plautdietsch Gortiz or Ooltkelnie , Ukrainian Khortytsia / Хортиця, Russian Chortitza / Хортица) is a former russlandmennonitische settlement colony northwest of Dneprinsel Khortytsia and is now partly in the city of Zaporizhia and in the Rajonen Zaporizhia ( Zaporizhia Oblast ) and Tomakivka ( Oblast Dnipropetrovsk ) in Ukraine .

The first settlement of this colony with the name Chortitza was founded in 1789 by Mennonite settlers from West Prussia and consisted of several villages. It was the first Mennonite settlement in Russia, which was later followed by others. After the move and the deportation of the Germans at the end of the Second World War , the majority of Ukrainians and Russians live in these villages, as far as they still exist today.

history

Mennonites of originally Dutch origin lived in the Vistula Delta in West Prussia from around the middle of the 16th century . Because their numbers grew steadily there, the settlers constantly needed new land. When West Prussia came to the Kingdom of Prussia in the course of the Polish partitions in 1772 , laws were passed by the Prussian government that made it difficult for the Mennonites to acquire land. As a result, large parts of the Mennonite population became impoverished and were forced to move to the surrounding cities, especially Danzig.

In 1763, Catherine II issued a manifesto inviting German farmers to Russia , which was propagated by advertisers in Germany. One of them was Georg von Trappe, who visited the Mennonites in Danzig in 1786 . On his mediation, two emissaries were sent to Russia: Jakob Höppner and Johann Bartsch . After negotiations with the Russian government, a. the following conditions agreed:

- Religious freedom

- Exemption from military service

- 65 Desjatin free land for every family

The settlement was to take place on the Dnieper bank, near the present-day city of Kherson. These lands had only recently come under Russian rule. After the emissaries returned, Mennonite settlers set out for Russia in the winter of 1787/88. A total of 228 families arrived in Dubrovno (today in Belarus) in autumn 1788 , where they wintered. In the spring of 1789 they traveled to the settlement site on the Dnieper River. Since the originally agreed location was too close to the theater of war, they had to relocate and were given land across from today's island of Khortitza , near today's city of Zaporizhia (then Alexandrowsk ). The entire colony got its name from this island. In the next few years more settlers came - by 1797 a total of around 400 families from West Prussia are said to have come to Russia.

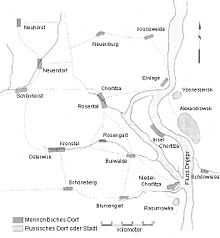

The beginning of the settlement took place under difficult conditions. On the one hand, the help of the Russian government arrived only slowly, on the other hand the settlers were internally divided and without spiritual guidance. Over time, 21 villages were founded:

| Surname | Ukrainian name | Russian name | founding year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Flower garden | Kapustjane / Капустяне (also Kapustjanka / Капустянка; no longer exists as a place, only a field name) | Kapustjanka / Капустянка | 1824 |

| 2. Burwalde | Baburka / Бабурка | Baburka / Бабурка | 1803 |

| 3. Chortitza | Khortytsia / Хортиця (since December 18, 2008 an independent place before the district of Zaporizhia) | Chortitza / Хортица | 1789 |

| 4. Deposit | Kitschkas / Кічкас (today in the north of Zaporizhia in Lenin district ) | Kitschkas / Кичкас | 1789 |

| 5. Chortitza Island | Ostriw Khortyzja / Острів Хортиця (today in the urban area of Zaporizhia) | Ostrow Chortitza / Остров Хортица | 1789 |

| 6. Gerhardstal | Tschernohlasowka / Черноглазовка (no longer localizable, near Tscherwonyj Yar ) | Chernoglasovka / Черноглазовка | 1860 |

| 7. Kronsfeld | Udilenske / Уділенське | Udelenskoje / Уделенское (older Khutor Udelnenskij) | 1880 |

| 8. Mariental | Prydniprowske / Придніпровське | Pridneprovsky / Приднепровское | ? |

| 9. Alt-Kronsweide (later also Bethania) | Velykyj Luh / Великий Луг (today a part of Zaporizhia) | Veliki Lug / Великий Луг | 1789 |

| 10. Neu-Kronsweide | Volodymyrivske / Володимирівське | Vladimirovkskoye / Владимировское | 1833 |

| 11. Neuchâtel | Malyshivka / Малишівка | Malyshevka / Малышевка | 1789 |

| 12. Neuhorst | Selenyj Haj / Зелений Гай (formerly Ternuwate / Тернувате) | Selenyj Gaj / Зеленый Гай (Ternuwatoje / Тернуватое) | 1824 |

| 13. Alt Rosengart | Novoslobidka / Новослобідка | Novoslobodka / Новослободка | 1824 |

| 14. New Rosengart | Schmeryne / Жмерине | Schmerino / Жмерино | 1878-80 |

| 15. Osterwick | Pawliwka / Павлівка (now part of Dolynske ) | Pavlovka / Павловка | 1812 |

| 16. Rose Valley | Kanzeriwka / Канцерівка (today partly in the urban area of Zaporizhia) | Kanzerowka / Канцеровка | 1789 |

| 17. Schöneberg | Smoljane / Смоляне | Smoljanoje / Смоляное | 1816 |

| 18. Schönhorst | Rutschajiwka / Ручаївка | Rutschajewka / Ручаевка | 1789 |

| 19. Schönwiese | ? (today the southern part of Zaporizhia) | Schenwise | 1797 |

| 20. Kronsthal | Kronstal / Кронсталь, Dolynsk / Долинск | Dolinsk / Долинск | 1809 |

| 21. Neuendorf | Shyroke / Широке | Shirokoye / Широкое | 1789 |

When the next wave of Mennonite settlers came to Russia in 1803 to found the Molotschna colony , the new settlers wintered with their fellow believers in Chortitza. Because they spent money there, it also helped the settlement of Chortitza. Eventually the economy in Chortitza got going and the settlement blossomed. During the 19th century the population of Chortitza multiplied, so that daughter colonies were founded. Some also moved to Canada after 1870. Since Chortitza was founded as the first Mennonite settlement, it is also called the old colony. The descendants of emigrants from Chortitza in North America partly as Old Colony Mennonites-Mennonites (English: Old Colony Mennonites ) referred, they are more conservative than most other Mennonite immigrants from Russia in North America.

When it was founded, many craftsmen came to Chortitza, who, when the settlement overcame the first economic difficulties, were able to practice their craft. From the middle of the 19th century, industry developed in Chortitza, especially milling, agricultural machinery and clock production. The growing landless population could also find work in the factories. Three large factories: Lepp & Wallmann, Abram J. Koop, Hildebrand & Pries and two smaller factories Thiessen and Rempel manufactured agricultural machines in Chortitza and Rosental. The agricultural machinery produced were not only intended for the Mennonites in Russia to consume themselves. A merger of three large factories resulted in a company that later (after the 1917 revolution) produced tractors and cars of the Zaporozhets brand . Today the company belongs to Zaporisky Avtomobilebudiwny Zavod (ZAZ) . The former Mennonite owners were expropriated shortly after 1917.

After a long prosperity, the World War (1914–1918) and the subsequent civil war brought about a turning point in the lives of the residents of Chortitza. During the war, the Mennonites had to serve as paramedics. They looked after injured soldiers there. After the war, the Ukraine and with it the settlement of Chortitza were briefly occupied by the German army. When Germany lost the war against the Entente at the end of 1918, the soldiers had to be withdrawn. The German army therefore organized the Russian-German self-protection and supplied them with weapons. Mennonites also took part in self-protection, although they were originally against the use of weapons for religious reasons. Because of the communist takeover of power in 1917, the civil war arose which lasted until around 1921. During this time Ukraine was in chaos. The wealthy German colonies were attacked by various gangs. Nestor Machno did a particularly good job . For a while they tried to defend themselves with the help of the self-protection organization. When Machno finally allied itself with the Soviet government, one had to give up. The Mennonite settlements were cleared for robbery.

After the communists took control of the area, they began to extort the rural population with food contributions. Eventually people began to starve and epidemics spread. During this time the Mennonite emigration to Canada began to be organized. When the situation normalized, many people emigrated in the 1920s, including to Paraguay , where the Fernheim colony was founded around 1930 .

During the construction of the DneproGES dam on the Dnieper in 1926, the village of Einlage had to be relocated due to flooding. Like many other Mennonites, Chortitza suffered from deculacization in the 1920s and collectivization in 1930. When the Second World War began in 1941, the inhabitants of Khortitza were to be deported to Siberia according to the will of the Soviet government. Since the Wehrmacht was advancing so quickly, these plans could not be realized. Under the German occupation, the population of Chortitza was able to recover a little. But as early as 1943 the German population had to be evacuated to the Warthegau because the Wehrmacht had to withdraw from the Soviet Union. When the Red Army marched into Germany, they got hold of these refugees. Some were able to save themselves further inland. But they too had to be extradited to the Soviet Union by the Allies as Soviet citizens. With a few exceptions, the former residents of Chortitza were deported to Siberia and Kazakhstan. There they were often abandoned in the bare steppe. Many did not survive. They had to share the fate of the other Russian Germans. After the commandant's office was abolished in 1956 (restrictions on freedom of movement), only a few returned to their old homeland, Chortitza. Ukrainians and Russians live there today. The few Mennonites still living there have either Russian parents or spouses. In Kazakhstan , the Mennonites often gathered in the emerging industrial cities such as Karaganda .

Finally, at the end of the 1980s, they began to emigrate to Germany. Today most of the surviving former residents of Chortitza and their descendants are in Germany.

Sons and daughters of the Mennonite settlement of Khortytsia

- Johann Bartsch , delegate of the Mennonites, co-founder of the colony

- Jakob Höppner , delegate of the Mennonites, co-founder of the colony

- Behrend Penner , first Mennonite community elder in Chortitza

- Hermann Niebuhr , founder of a milling company and the Chortitza commercial bank

- Peter Lepp and Andreas Wallmann , founders of the Lepp & Wallmann factory

- Abram J. Koop , founder of an agricultural machinery company

- Kornelius Hildebrand and Peter Priess , founders of the Hildebrand & Priess company

- Cornelius Krahn , German-Ukrainian theologian, university professor for church history, author and editor of standard works on the history of the Mennonites

literature

- Walter Kuhn : The old Mennonite colony Chortitza in the Ukraine. In: Deutsche Monatshefte 9 (19), Posen 1942, pp. 161–199.

- Adina Reger, Delbert F. Plett: These stones. Crossway Publications, 2001, ISBN 1-55099-124-8 .

Web links

- Private website with maps, photos, genealogy and data

- German colonies in Russia and Ukraine

- Plautdietsch Friends eV

- Soviet general staff map of the area as of 1990 ( memento of March 11, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

Coordinates: 47 ° 52 ' N , 35 ° 1' E