Lux Guyer

Lux Guyer , actually Luise Guyer, (born August 20, 1894 in Zurich ; † May 26, 1955 there ) was a Swiss architect .

Life

Guyer was born as the daughter of a primary school teacher in Zurich and grew up with two sisters. After primary, secondary and daughter school ( canton school ), she attended courses in interior design with Wilhelm Kienzle at the Zurich School of Applied Arts in 1916/17 and was a specialist student at the Polytechnic ( ETH Zurich ) in 1917/18 . It is not known why she did not enroll at ETH. She also worked part-time in Gustav Gull's office in Zurich.

From 1918 to 1924 she expanded her architectural knowledge and skills on study trips to Paris, Florence, Berlin (in the office of the first German architect Marie Frommer ) and London. She opened her own architecture office in Switzerland in 1924 and is the best-known of the independent Swiss architects of the early 20th century.

In 1930 Guyer married the ETH civil engineer Hans Studer and had a son (Urs). Despite the crisis after the Second World War , she continued to run the architectural office under her name.

After her death in 1955, her niece Beate Schnitter (* 1929) took over the office.

In 1995 the Lux-Guyer-Weg in the Unterstrass district of Zurich , which leads from the Kornhausbrücke to the Dynamo youth culture center , was named after her.

plant

Guyer's works include private single-family houses as well as urban housing estates, dormitories (for example, in 1926/27 the Lettenhof women's colony for single women or in 1927/28 the Fluntern dormitory ) and residential buildings in suburban locations. Guyer was the leading architect of the Swiss Exhibition for Women's Labor ( SAFFA ) in Bern (1928) and created the SAFFA-Haus prefabricated wooden house . She realized a significant part of her buildings between 1925 and 1935, the decade in which classical modernism reached its peak. After 1935 she built more traditional and artisanal houses. Guyer's home in Küsnacht , the “Sunnebüel”, is now a protected property of national importance.

"Lux Guyer was an architect who was interested in modernity in the sense of freedom from social and cultural prejudices, freedom from restrictive dogmas of any kind." Even for their time, the buildings were quite unconventional and had to be lived in exemplary before they found buyers. Guyer's architecture was anti-representative and non-hierarchical, it was a collage of different modules. The rooms are loosely connected, often accessed several times, and can thus fulfill various functions without remaining undefined. Lighting and lines of sight play a central role, as is the deliberate, varied design of surfaces and colors, floors, walls and ceilings. "These two criteria - atmosphere and mobility - seem to make up the core of what Lux Guyer saw as her approach to modern living [...]."

Honor

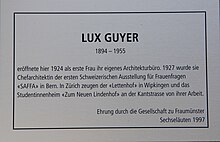

Lux Guyer was honored for her work on the occasion of the Sechseläuten in 1997 by the Gesellschaft zu Fraumünster . A memorial plaque is located at Bahnhofstrasse 71 in Zurich.

Fonts

- Autobiography, in: Elga Kern (Hrsg.): Leading women in Europe . In 25 self-descriptions. New episode. E. Reinhardt, Munich 1930, pp. 64-69.

literature

- Dagmar Böcker: Guyer, Lux. In: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz .

- E. Rudolf: Housing colony for single women in Lettenhof Zurich . In: Das Werk: Architektur und Kunst, Volume 15, 1928, Issue 5.

- Sylvia Claus, Dorothee Huber, Beate Schnitter (eds.): Lux Guyer (1894–1955). Architect . gta Verlag, Zurich 2009, ISBN 978-3-85676-240-7 .

- The three lives of the Saffa house . Lux Guyers model house from 1928. gta Verlag, Zurich 2006, ISBN 3-85676-198-5 .

- Verena Bodmer-Gessner: The Zurich women. A brief cultural history of Zurich women. Report House, Zurich 1961, pp. 121–123; Pp. 153-154.

- Susann L. Pflüger: New Year's Gazette of the Fraumünster Society for 2010, Volume 4, fourth piece. Edition Gutenberg, Zurich 2010, ISSN 1663-5264 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Auditors do not have student status and therefore cannot acquire an ETH degree or an ETH diploma. The first female architect, Flora Steiger-Crawford from Scotland, graduated from ETH in 1923. History of women at ETH

- ↑ Verena Bodmer-Gessner: The Zurich women. A brief cultural history of Zurich women. Report House, Zurich 1961, p. 121.

- ↑ Lux Guyer, architect and construction pioneer

- ↑ gta 50 ETHZ: Lux Guyer (1894–1955)

- ↑ nextroom.at: Lux Guyer, Zurich

- ↑ Houses of famous Küsnachters , on kuesnacht.ch

- ↑ Ulrike Eichhorn : Architects. Your job. Your life . Edition Eichhorn, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-8442-6702-0 .

- ↑ Beate Schnitter (Küsnacht ZH): The house of a famous aunt and a life's work for building culture , on Kulturerbe2018.ch (published June 13, 2018, accessed February 10, 2019).

- ^ Hans Bernoulli : The buildings of the Saffa. In: Das Werk Vol. 15 (1928), No. 8, pp. 226-231, doi: 10.5169 / seals-15200 .

- ^ Bettina Köhler: The Japanese Maiensäss. Lux Guyer, the reform and the atmosphere (s). In: Sylvia Claus, Dorothee Huber, Beate Schnitter (eds.): Lux Guyer (1894–1955). Architect. gta Verlag, Zurich 2009, ISBN 978-3-85676-240-7 , pp. 25–41, here p. 25.

- ↑ Paragraph after Bettina Köhler: The Japanese Maiensäss. Lux Guyer, the reform and the atmosphere (s). In: Sylvia Claus, Dorothee Huber, Beate Schnitter (eds.): Lux Guyer (1894–1955). Architect. gta Verlag, Zurich 2009, ISBN 978-3-85676-240-7 , pp. 25–41; Verbatim quotations on pages 31 and 37 f.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Guyer, Lux |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Guyer, Luise (real name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Swiss architect |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 20, 1894 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Zurich |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 26, 1955 |

| Place of death | Zurich |