Magnetberg

The name Magnetberg is based on a belief in such a mountain in the Arctic , which researchers tried to substantiate scientifically as a supposed fact, especially in the 16th century, and which has been adopted in modern times to designate mountains with a high own magnetic polarity.

The magnetic compass had been known to the Western European peoples at least since the 12th century and it was assumed that the triggering cause was in the far north, namely a strong magnet. This theory arose from a work by the Oxford Franciscan Nicholas of Lynne , who reported on the Magnetberg in his work Inventio Fortunata as early as 1360.

As sea saga or sailor's thread , legendary stories play around the Magnetberg, in which ships are attracted or sink due to the loss of their iron nails. Also in the story of Sindbad the Navigator, but only in the later versions of the fairy tales from the Arabian Nights , the hero reaches the Magnetberg. Jules Verne processed this idea into Captain Hatteras' adventures . The motif is used again in modern fictional stories like Jim Knopf and the wild thirteen .

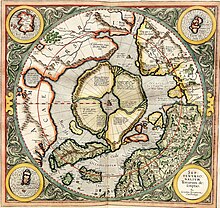

In the 16th century, the term was the name of the Arctic polar region, or it was assumed that it was precisely this magnetic mountain. The earth map by Johannes Ruysch from 1508 contains further information such as the location below the North Pole and that the mountain is a single rock with an extent of 33 German miles. Around it is the Amber Sea and in it four islands, two of which are inhabited. The mountain thus forms an island and also implies a theory of the ice-free Arctic Ocean . The English geographer Richard Hakluyt took up this again in his work The principal navigations, voyages and discoveries of the English Nation . Gerhard Mercator described the Magnetberg in 1577 in a letter to John Dee .

James Cook named a mountainous island off the Western Australian coast Magnetic Island because he registered a strong compass deviation. Alexander von Humboldt referred to the Haidberg near Zell in the Fichtelgebirge as a "magnetic mountain" after he had discovered during his geological explorations that its serpentinite rock is partially strongly magnetized. The gabbro of the Ilbes mountain in the Frankenstein massif (Odenwald) shows similar magnetic properties, which is why this mountain is also commonly referred to as the "magnetic mountain". Probably the most famous real existing "magnetic mountain" is in the Urals : Magnitnaja Gora (Магнитная гора) with its magnetite iron ore deposit gave the city of Magnitogorsk , a symbol of the Stalinist transformation of the Soviet Union to an industrial nation , its name.

swell

- Nicholas of Lynne : Inventio Fortunata . 1360.

- Johannes Ruysch : Ruysch's world map . 1508.

- Olaus Magnus : Carta Marina . 1539.

- Richard Hakluyt : The principal navigations, voyages and discoveries of the English nation etc. 1589. (English)

- Gerhard Mercator , various cards

Sagas and stories

- Sindbad , Arabian Nights , Sea Say

- Jules Verne : Adventure of Captain Hatteras . 1875.

- Michael Ende : Jim Button and the Wild 13 . Thienemann , Stuttgart since 1962 in various editions, current NA: 978-3-522-17651-4; Paperback edition: Carlsen, Hamburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-551-31307-2 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Eva GR Taylor : A Letter Dated 1577 from Mercator to John Dee. In: Imago Mundi: The International Journal for the History of Cartography. Vol. 13, No. 1, 1956, pp. 56-68, doi : 10.1080 / 03085695608592127 (alternatively: JSTOR 1150242 ).

- ↑ Hughes, Holly; Murphy, Sylvie; Flippin; Alexis Lipsitz; Duchaine, Julie: Frommer's 500 Extraordinary Islands . John Wiley & Sons, 2010, ISBN 978-0-470-59518-3 , p. 357.

- ^ Frank Holl , Eberhard Schulz-Lüpertz: I made such big plans there ... Alexander von Humboldt in Franconia . Franconian History, Vol. 18. Gunzenhausen: Schrenk, 2012. ISBN 978-3-924270-74-2 . P. 114f.