To my adorable grandmother on her 72nd birthday

For my venerable grandmother on her 72nd birthday is a poem by Friedrich Hölderlin . The addressee was his maternal grandmother Johanna Rosina Heyn née Sutor (born December 30, 1725 in Hattenhofen (Württemberg) , † 1802).

Origin and tradition

The poem was written in Homburg , where Hölderlin on the advice of his friend Isaac von Sinclair was taken in September 1798 after he from the house of the Frankfurt merchant Jakob Friedrich Gontard-Borken Stein (1764-1843) and of his wife Susette Gontard , his Diotima , had separated.

On January 1st, 1799 he wrote to his half-brother Karl Gok : “Also these days a letter from our dear mother, where she expressed her joy at my religiosity, and asked me, among other things, our dear 72-year-old grandmother to write a poem for her birthday to do, and many other things in the unspeakably moving letter so moved that I spent the time when I might have written to you mostly with thoughts of her and you loved ones in general. I also have a poem for the l. The same evening that I received the letter. Grandmother started it and almost finished it that night. I thought that the good mothers should be happy if I sent off a letter and the poem the next day. But the notes I touched resounded so powerfully in me again, the changes in my mind and spirit that I had experienced since my youth, the past and present of my life became so palpable to me that I could not find sleep afterwards , and the next day had trouble getting myself together again. "

- Newspaper for the Elegant World 1824

Hölderlin enclosed the poem in an undated letter from January 1799 to his mother in Nürtingen : “Dearest mother! I have to be ashamed that I am your l. Letter which, however, gave me so many dearly happy hours and moments, has not answered for so long. The same evening I received it, I wrote down for the most part what I am enclosing for my dear venerable grandmother, and I thanked you from the bottom of my heart for informing me of this birthday, which is sacred to me. <...> Goodbye, dearest mother! ask dear Mrs. Grandma to take the sheet as a small part of the joyful and serious feelings with which I celebrated my venerable birthday in my heart. My heartfelt recommendations to all of us. Your faithful son Friz. "

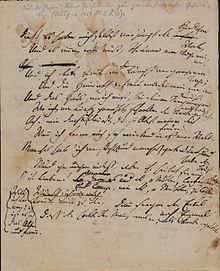

Verses 21 to 34 are preserved as an autograph on the back of a letter from Karl Gok to Hölderlin. The whole poem has come down to us in two copies by an unknown hand. It was first printed in No. 146 of the newspaper for the elegant world of July 1824. In a footnote, perhaps written by Karl Philipp Conz, it says: “There may be a collection of poems by this witty 'through being' around this year en> Hyperion, and several well-known poetry published in the Horen, the Almanacs and other magazines, and whose effectiveness has been restrained for many years by an unfortunate fate, this may be the present one, which the sender found among his papers, should it be already printed, for example, to draw the public's attention to the upcoming appearance of his selection. "

Hölderlin is quoted here from the historical-critical Stuttgart edition of his works published by Friedrich Beissner , Adolf Beck and Ute Oelmann (* 1949) . The texts of the poem in the historical-critical Frankfurt edition and the "reading edition" by Michael Knaupp differ from the Stuttgart edition only by an additional comma at the end of verse 17. In the reading edition by Jochen Schmidt , the orthography is "modernized".

text

You experienced a lot for my venerable grandmother on her 72nd birthday , dear mother! and now rest happily, lovingly called by name from far and near, also heartily honored to me in the silver crown of old age among the children who mature and grow and blossom for you. 5 Long life has won you the gentle soul And the hope that gently led you into suffering. Because you are satisfied and pious, like the mother who once gave birth to the best of men, the friend of our earth. - oh! they do not know how the high man walks among the people, 10 and what the living was almost forgotten. Few know him and often the heavenly picture appears to them amusing in the midst of stormy times. All-conciliatory and quietly with the poor mortals he went, That one man, divine in spirit. 15 None of the living were shut out of his soul, And he bore the sufferings of the world on a loving breast. With death he befriends, on behalf of the others he went back to his father victorious out of pain and labor. And you know him too, you dear mother! and walk 20 Feeling and duldend and nursing him, the sublime after. Look! I myself have been rejuvenated by childlike words, And tears still run from my eyes, as they once did; And I think back to days long past, And home again delights my lonely mind, 25 And the house where I once grew up with your blessings by the sea, Where, nourished by love, the boy thrived faster. Oh! How do I often think you should be happy about me , When I saw myself far away working in the open world. Some things have I tried and dreamed and had my breast 30 , however, struggled wound, but you do heal me, O my friends! and long as you, O mother! I want to learn to live ; it is calm old and pious. I want to come to you; then bless the grandson once more, That the man will keep what he, as a boy, vows to you.

Composition, background

Johanna Rosina Heyn, the grandmother, lived mainly with Hölderlin's mother since she was widowed in 1772 and played a major role in Hölderlin's upbringing. December 30, 1798 was her 73rd, not her 72nd birthday. Holderlin also mentioned it in the poem from his Maulbronn time, 1786, Die Meinige : “O! and she in pious silver hair, / Who runs so hot the children's tears of joy, / Who looks back so great on so many beautiful years, / Who calls me so well, so lovingly, grandchildren / <...> Let, oh let them enjoy for a long time / Your years of rewarding memory, / Let us all sweeten your every moment, / striving, like you, for sanctification. "

The poem is written in distiches . The first six verses address the grandmother as "you dear", "dearly honored <e>", praising her "gentle soul" and her hope even in suffering.

The middle verses 7 to 20 primarily speak of the piety and piety of the grandmother. They gain their deeper meaning in the context of Holderlin's argument with his mother about his own Christianity. On December 11, 1798 he had written to his mother: “Dearest mother! You have sometimes written to me about religion as if you didn't know what to think of my religiosity. Oh, could I open my innermost part of you all at once! - Only that much! There is no living sound in your soul to which mine did not join in too. ”The mother had answered with joy. In the undated letter of January 1799 already quoted above, Holderlin reacted positively exuberantly; his mother gave him "many heartily happy hours and moments". He continues: “The fact that you received my utterances on religion with this most beautiful of all joys testifies to me so completely of the soul which only finds its calm in the highest. I believe you, dearest mother! how it must make the memory of me easier and cheer for you when you know the best feelings of a human soul in me and can hold onto them in the doubts and worries with which even the best have to consider each other, and the dearer they are, the more, because we hardly know ourselves, and as known as we are to ourselves, we will never be anything else. I reserve the right to make a complete profession of faith with you at more leisure, and I wish I could express my opinion everywhere in my heart as openly and purely as I can with you. "

Holderlin never made a “complete creed of faith” to his mother in a letter, but the poem is the core of such. Verses 7 and 8 compare the grandmother with Mary, the “mother who once bore the best of men, the friend of our earth”. Verses 8 to 20 imply Holderlin's approval of the grandmother's faith in Jesus Christ as the divine Savior who suffers on behalf of people.

According to Roland Reuss , "suras from a new Hölderlinian preoccupation with the figure of Christ come to light here for the first time - a discussion that should culminate in Patmos , in particular , but also in Mnemosyne ". The length of the poem is calculated precisely with 34 verses; for since Eusebius it was taken for granted that Jesus had been crucified at the age of 34; the crucifixion is also commemorated exactly in the middle of the 17 distiches, i.e. verses 17 and 18.

The last verses, 21 through 34, express the poet's feelings while writing. As a boy he wanted to work “in the open world”. He tried a lot and "<w> and struggled" (verse 30). The “loved ones” (verse 31), he hopes, will heal him, just as he hopes in the extended version of the Ode Die Heimath that “as in bonds my heart heal me” in their vicinity. “Old age is peaceful and serene” in the evening phantasy at about the same time , there with a resigned undertone that is missing in the poem for the grandmother, which closes with a request for her blessing.

reception

Pope Francis , who counts Holderlin among his favorite poets, called the poem to the grandmother in an interview "of great beauty, also spiritually very beautiful." It touched him because he also loved his grandmother very much. “And there Holderlin places his grandmother next to Mary, who gave birth to Jesus. For them he is the friend on earth who did not regard anyone as a stranger. "

literature

- Friedrich Hölderlin: Complete Works. Big Stuttgart edition . Edited by Friedrich Beissner, Adolf Beck and Ute Oelmann. Kohlhammer Verlag , Stuttgart 1946 to 1985.

- Friedrich Hölderlin: Complete Works . Historical-critical edition in 20 volumes and 3 supplements. Published by DE Sattler . Frankfurt edition. Stroemfeld / Roter Stern publishing house , Frankfurt am Main / Basel 1975–2008.

- Friedrich Hölderlin: Poems. Edited by Jochen Schmidt. Deutscher Klassiker Verlag , Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-618-60810-1 .

- Friedrich Hölderlin: All works and letters. Edited by Michael Knaupp. Carl Hanser Verlag , Munich 1992 to 1993.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Stuttgart edition, Volume 6, 1, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Stuttgart edition, Volume 6, 1, pp. 308 and 314.

- ↑ Stuttgart edition, Volume 1, 2, p. 594.

- ↑ Stuttgart edition Volume 1, 1, p. 20.

- ↑ Stuttgart edition, Volume 6, 1, p. 297.

- ↑ Stuttgart edition, Volume 6.1, p. 309.

- ↑ Roland Reuss: "... / The other's own speech". Hölderlin's 'Memory' and 'Mnemosyne'. Stroemfeld / Roter Stern , Basel / Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-87877-377-3 , p. 364.

- ↑ Stuttgart edition. Volume 2, 1, p. 19.

- ↑ Stuttgart edition. Volume 1, 1, p. 301.

- ^ Antonio Spadaro: The interview with Pope Francis. Part 2. In: Voices of the time. online, November 2013. Retrieved September 17, 2014.