Socrates and Alcibiades

Socrates and Alcibiades is the title of a short ode by Friedrich Hölderlin that was written during his time in Frankfurt am Main . It belongs to a group of five poems that he sent on June 30, 1798 to Friedrich Schiller , who published it in his Musenalmanach for 1799 . The dialogical poem contrasts question and answer antithetically.

The work in two stanzas has asklepiadic stanzas and is one of the abbreviations which, with their epigrammatic conciseness, document Hölderlin's mastery in this form.

content

The two stanzas are:

"Why do you pay homage, Saint Socrates,

To this young man always? don't you know greater?

Why see with love

How about gods, your eye on him? "

He who has thought the deepest loves the most vital,

High youth understand those who look out into the world

And the wise ones tend

Often in the end to be beautiful.

Background and special features

As far as the use of ancient stanzas is concerned, Hölderlin's poems are considered the climax in the development of the German-language ode. Since he published a comparatively large number of them, he became known to his contemporaries as a poet between 1799 and 1806. He received well-founded and encouraging as well as uncomprehending and negative reactions. Already in the first phase between 1786 and 1789 in Maulbronn and Tübingen , in which there was no publication, Alcalic stanzas predominated.

After an intermediate phase, Hölderlin turned to this genre again in Frankfurt and wrote mostly epigrammatic shorts with only two or three stanzas, turning away from the previous phase of rhyming hymns and moving through to more concise diction and more concise formulation. The stanza relation was reversed compared to the first ode phase, in that three Alkaean now stand against nine asklepiadic stanzas. Their falling rhythm and their uniformity suited the brief statement of the poems of this phase.

In addition to political questions, he was concerned with problems of artistic perfection, which he asks for in his famous poem An die Parzen , or topics such as the torn reality: After Diotima, idealized in many poems and his Hyperion, briefly took shape for him with Susette Gontard , he described the agonizing relationship between this “holy life” and the incomprehensible environment.

In Socrates and Alcibiades in particular , Hölderlin succeeded in underlining the tense contrasts with the meter of the Asclepiadic stanza and in contrasting them in the first pair of verses.

This becomes particularly clear in the second stanza with Socrates' answer:

Who the deep ste ge thoughtful , loves Le ben digs te / Ho Hey Ju quietly ver is , who in the world ge looks

Both verses are small asclepiades according to the metrical scheme

- —◡ — ◡◡— | —◡◡ — ◡—

By meeting the stressed syllables , they clarify the difference in content ( whoever thought the deepest - loves the most lively ), while the context is syntactically recognizable. Wolfgang Binder pointed out the chiasm of the stanzas, in that “the deepest” and “the world” on one side and “the most lively” and “high youth” on the other side are arranged crosswise, thus also making the contrast recognizable.

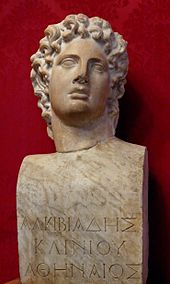

Alkibiades , brilliant orator and statesman, was a pupil of Socrates and was considered the epitome of youthful beauty. While he was the last speaker in Plato's symposium to praise Socrates, speak of his wisdom and frugality, praise his bravery in the war and describe how he had endured the troubles of winter, Holderlin reversed the relationship and had Socrates pay homage to Alcibiades. For Holderlin, the beautiful was a symbol of the divine and the content of poetry . In Hyperion love connects the finite with the infinite, is a reconciling force, a transcendent striving of eros.

interpretation

Walter Hinderer considers the ode on the relationship between wisdom and beauty in the famous homoerotic relationship to be one of the most astonishing lyrical events in the German language. The banausal question to “Saint Socrates”, why he especially loves the reckless youth so much, leads to the center of Platonic love , which in the sense of the symposium is about expansion and completion. She wants to transcend the physical object of inclination in favor of the idea . As Socrates puts it in the mouth of his teacher Diotima, the stranger from Mantineia , who speaks of the intrinsically beautiful beyond the beautiful body, which is not covered by the externals and should extend to the recognition of the primal beauty, this idea is precisely the “creation and Birth in beauty. ”For Hinderer, the three epigrammatic answers to the last stanza amount to a harmonization of opposites, from deep thinking to love, from youth to the experience of old age, from wisdom to beauty.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Andreas Thomasberger: Oden, phases of the Odendichtung, in: Hölderlin-Handbuch. Life work effect . Metzler, Stuttgart and Weimar 2011, p. 309

- ↑ Friedrich Hölderlin, Sokrates und Alcibiades, in: All poems, Deutscher Klassiker Verlag im Taschenbuch, Volume 4, Frankfurt 2005, p. 205

- ↑ Andreas Thomasberger: Oden, phases of the Odendichtung, in: Hölderlin-Handbuch. Life work effect . Metzler, Stuttgart and Weimar 2011, p. 309

- ↑ Jochen Schmidt , commentary in: Friedrich Hölderlin, Complete Poems , Deutscher Klassiker Verlag im Taschenbuch, Volume 4, Frankfurt 2005, p. 490

- ↑ Andreas Thomasberger: Oden, phases of the Odendichtung, in: Hölderlin-Handbuch. Life work effect . Metzler, Stuttgart and Weimar 2011, p. 309

- ↑ Andreas Thomasberger: Oden, phases of the Odendichtung, in: Hölderlin-Handbuch. Life work effect . Metzler, Stuttgart and Weimar 2011, p. 312

- ↑ Andreas Thomasberger: Oden, phases of the Odendichtung, in: Hölderlin-Handbuch. Life work effect . Metzler, Stuttgart and Weimar 2011, p. 312

- ↑ Bärbel Frischmann , Hölderlin and the early romanticism, in: Hölderlin-Handbuch. Life work effect . Metzler, Stuttgart and Weimar 2011, p. 112

- ^ Walter Hinderer, Im Wechsel das Vollendet, in: 1000 German poems and their interpretations, ed. Marcel Reich-Ranicki, Von Friedrich Schiller bis Joseph von Eichendorff, Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig 1994, p. 124

- ↑ Walter Hinderer, Im Wechsel das Vollendet, in: 1000 German poems and their interpretations, ed. Marcel Reich-Ranicki, From Friedrich Schiller to Joseph von Eichendorff, Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig 1994, p. 123