CV (Hölderlin)

The curriculum vitae is an ode in asklepiadic meter by Friedrich Hölderlin . Hölderlin wrote a first, single-verse version in mid-1798. He expanded it to the second, four-verse version in the summer of 1800. The single-verse version is one of his “epigrammatic odes” . Taking one and four verse versions together, one has spoken of a “poetic marvel”.

Lore

Hölderlin sent the single-verse version in June and August 1798 together with 17 other "epigrammatic odes" to his friend Christian Ludwig Neuffer for his paperback for women of education . Neuffer published his curriculum vitae in the year 1799. Hölderlin's manuscript is preserved in the Bibliotheca Bodmeriana , on a sheet of paper which also contains the poems Ehmals and Jezt and, overleaf, The Brief .

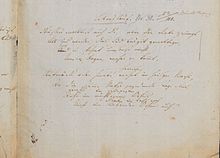

The four-stanza version first appeared in 1826 in the collective edition of the "Poems" organized by Ludwig Uhland and Gustav Schwab . There are several manuscripts in the Württemberg State Library in Stuttgart, including the provisional fair copy shown here, in which Hölderlin later made changes.

Hölderlin is quoted here after the historical-critical Stuttgart edition of his works that Friedrich Beissner , Adolf Beck and Ute Oelmann (* 1949) provided . The historical-critical Frankfurt edition published by Dietrich Sattler and the "reading edition" by Michael Kaupp offer identical texts of the poem. The "reading editions" by Gerhard Kurz and Wolfgang Braungart as well as Jochen Schmidt are orthographically "modernized".

Texts

CV

's to target my mind, but love drew Nice him down; the laid bends it more powerfully; In this way I go through life's arc and return where I came from.

CV

You wanted bigger too, but love forces all of us down; the laid bends more powerfully; But our bow does not return in vain where it comes from. Up or down! reigns in holy night, Where mute nature ponders days that are becoming, Is there not a degree, nor a right , in the most crooked orcus ? I found out about this. For never, like mortal masters, Have you heavenly ones, you all-sustaining, that I knew, led me with caution on the level path. Let man examine everything, say the heavenly ones, That he, strongly nourished, give thanks for learning everything, and understand the freedom to set off wherever he wants.

interpretation

Holderlin dresses human life in the image of the bow, as did Heraclitus , who played with the similarity of the Greek words for "life" ( βίος , bíos ) and "bow" ( βιός , biós ). In the single-verse version he restricts himself to his own biography. In the four-stanza version, the first stanza of which repeats the single-verse poem with few but drastic changes, it transcends the subjective, the individual, the personal and reflects on human existence in general. The single-verse version speaks of gentle resignation, the four-verse heroic self-assertion.

Single-verse version

Hölderlin tries to grasp his own life and experience, he speaks of himself with personal and possessive pronouns of the first person. If he had previously strived for the immeasurable ideal, for example in the Tübingen hymn of 1790 To immortality “No, immortality, you are, you are!”, Love has now “beautifully drawn him down”. In the first print it says "Bald him down", probably an arbitrary change by Neuffer. In real life, Hölderlin experienced his love for Susette Gontard as beautiful; in Susette, “beauty” was revealed to him. At the same time as the “epigrammatic odes”, Hölderlin's novel Hyperion was written in Frankfurt . The love of Diotima in the novel leads the hyperion of the novel to the conception of “beauty” as the absolutely perfect. "Hyperion does not only mean the external appearance, but even more the ideal being in its all-harmony." Hyperion writes to his correspondent Bellarmin:

“I have seen it once, the only thing my soul was looking for, and the perfection that we remove above the stars, that we push out until the end of time, that I have felt at present. It was there, the highest, in this circle of human nature and things it was there!

I no longer ask where it is; it was in the world, it can return in it, it is now only more hidden in it. I no longer ask what it is; I've seen it, I've got to know it. <...>

His name is beauty. "

With the love for Susette Gontard there has also come sorrow, which now "bends" him - the present tense, like the pronouns of the first person, shows the concentration on one's own life. The poet seems to come to terms with his skill - the verbs remain in the present tense: "So I go through life / arc and return where I came from." Rescission is an individual solution. “This first version of the poem thus offers a perfect picture of Holderlin's own spiritual development up to his separation from Diotima.” The question of the meaningfulness of a life drawn down by love and bent by suffering remains unanswered.

Four stanza version

The survey of one's own life and experience has become an survey of life in general. The first stanza, like the one stanza of the first version, captures the beginning, middle and end of life with an embracing movement. The "I" is deleted. The pronouns “you”, “all us” and “our” refer to the arc of life of all of humanity. “Holderlin talks about us all.” People who wanted “greater things”, wanted to burst open what is given, are forced down by love; Hölderlin takes up Virgil's famous phrase "omnia vincit amor" - "love conquers everything". “The laid bends more powerfully”, so powerfully that the object of bending, the human being, has completely disappeared. “Under the violence of suffering, man can no longer reflect on himself, so to speak, the purely sensual experience of bending violence takes him, the weak, withdrawn, completely.” But with “But <...> not in vain” comes in a new tone, an energetic rebellion, the attempt to understand and present the bending as positive.

The speaker no longer understands the movements "upwards or downwards" as better and worse, but as equivalent. Again Holderlin refers to Heraclitus: "ὁδὸς ἄνω κάτω μία καὶ ωὑτή" - "The way up down one and the same." The heroic keynote brings the mind to the limits of its imagination, into the "night", the "orcus" . "Rule on holy night, <...> rule in the most crooked Orkus / Not a degree, a right too?" According to the Germanist Ulrich Gaier (* 1935) from Konstanz , the apparently dubious rhetorical question requires a strong answer: "Yes ! ”Yes, even here there is“ a degree, a right ”. A little later, in the elegy Brod und Wein , Hölderlin wrote in a similar way : “Feast remains one; be it at noon or it goes / until midnight, there is always a Meuse / common to all. ”In the cosmos there is ultimately“ one degree, one right ”.

The third stanza justifies this assertion with personal experience: "I experienced this." For the first time the I appears. His own uneven life path has taught the speaker that rising and falling directions of life are of equal value to the self. The laconic sentence is followed by the deliberate reflection directed to the heavenly ones: You have never "led me on the level path".

The heavenly ones deign to answer. They, who from the start have the knowledge that is struggled for in the poem, confirm: “Everything” is examined by a person, for “everything” he should give thanks, for life, joys and sorrows, upwards and downwards. By affirming good and bad experiences, he gains the inner “freedom to / set off wherever he wants” and at the same time is “strongly nourished” for new beginnings. Eduard Mörike has the Agnes of his novel, painter Nolten 1832, pray: “Want to be with joy / And you want to be with suffering / Don't shower me! / But in the middle / there is lovely modesty. ”In contrast to Mörike, for Hölderlin what distinguishes people is that“ the heavenly ones let him draw from the overflow ”, with the extremes of highs and lows. Accepting this and obeying the principle of degrees and rights, he finds the meaning of his life course.

literature

- Elisabeth Borchers : The earthly and the heavenly. In: Marcel Reich-Ranicki (Ed.): Frankfurter Anthologie Volume 11, 1988, pp. 97-100.

- Ulrich Gaier: Attention levels. A Holderlin course. Website of the Hölderlin Society. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- Friedrich Hölderlin: Homburg Folioheft - Homburg.F. Digitized version of the Württemberg State Library, Stuttgart. Retrieved January 9, 2015.

- Friedrich Hölderlin: Complete Works. Big Stuttgart edition . Edited by Friedrich Beissner, Adolf Beck and Ute Oelmann. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart 1943 to 1985.

- Friedrich Hölderlin: Complete Works . Historical-critical edition in 20 volumes and 3 supplements. Edited by Dietrich Sattler. Frankfurt edition. Stroemfeld / Roter Stern publishing house , Frankfurt am Main and Basel 1975–2008.

- Friedrich Hölderlin: All works and letters. Edited by Michael Knaupp. Carl Hanser Verlag , Munich 1992 to 1993.

- Friedrich Hölderlin: Poems. Edited by Gerhard Kurz and Wolfgang Braungart. Philipp Reclam jun. , Stuttgart 2000. ISBN 3-15-056267-8 .

- Friedrich Hölderlin: Poems. Edited by Jochen Schmidt. Deutscher Klassiker Verlag , Frankfurt am Main 1992. ISBN 3-618-60810-1 .

- Jochen Schmidt: Hölderlin's ode "Curriculum Vitae" as a work of art and pantheistic program poem. In: Sabine Doering, Waltraud Maierhofer and Peter Philipp Riedl (eds.): Resonances. Festschrift for Joachim Kreutzer for his 65th birthday. Königshausen & Neumann , Würzburg 2000. ISBN 3-8260-1882-6 , pp. 203-209.

- Andreas Thomasberger: Odes. In: Johann Kreuzer (Ed.): Hölderlin Handbook, Life - Work - Effect, pp. 309–319. JB Metzler'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung , Stuttgart 2002. ISBN 3-476-01704-4 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Schmidt 2000.

- ↑ In the bundle "Die Heimath - Homburg.H, 15-18" of the Württemberg State Library.

- ↑ Stuttgart edition, Volume 1, 2, p. 565.

- ↑ Stuttgart edition, Volume 1, 1, p. 117.

- ^ Friedrich Hölderlin: Hyperion, Empedocles, essays, translations. Edited by Jochen Schmidt. Deutscher Klassiker Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-618-60820-9 , p. 953.

- ^ Stuttgart edition, Volume 3, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Curriculum vitae on the litde.com website. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ↑ Borchers 1988.

- ↑ Schmidt 1992, p. 677.

- ↑ Hölderlin could have written metrically correct "bows us mightier".

- ↑ Gaier p. 48.

- ↑ Schmidt 1992, p. 677.

- ↑ Gaier p. 51.

- ↑ Stuttgart edition, Volume 2, 1, p. 91.

- ^ Eduard Mörike: painter Nolten. Edited by Herbert Meyer. Ernst KLett Verlag , Stuttgart 1967, p. 386.

- ↑ Borchers 1988.