Moshe Leib Lilienblum

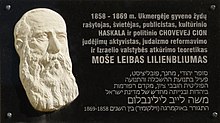

Mose Löb Lilienblum ( Moses Lilienblum / Moshe Leib Lilienblum , Yiddish משה לייב ליליענבלום, Hebrew משה לייב ליליינבלום; briefly as Moses Herlichstsohn, occasionally under a pseudonym: Zelaphchad Bar-Chuschim ; born on October 10th jul. / October 22, 1843 greg. in Kedahnen , Russian governorate Kovno [today Lithuania ]; died on January 30th jul. / February 12, 1910 greg. in Odessa ) was a Russian-Jewish scholar, Hebrew writer, Jewish reformer, and pioneer of early Zionism .

Life

Born as the son of the poor cooper Hirsch (Zvi) and his second wife, Lilienblum grew up in the pious Jewish community of his birthplace. From his father he learned how to calculate the planetary orbits in relation to the Jewish calendar . At the age of 13, he organized a boys' group to study ʿEjn Yaʿaqov ( Hebrew עין יעקב, Compilation of Talmudic-Aggadic material with commentary).

At this time already recognized as a learned boy with the potential for greater things, his future mother- in-law , wife of a butcher from Wilkomir , noticed him when she and her daughter were visiting graves of relatives in Kedahnen. She signed an engagement contract for her 11-year-old daughter and 13-year-old Lilienblum with his father. In it, she committed herself to provide maintenance for Lilienblums and her daughter for two years until the wedding and then for another five years.

At the age of 14 he moved to his future in-laws in Wilkomir, where the head of the local yeshiveh accepted him as a Bocher (student) and a. an uncle on his father's side also taught. At the age of 15 he married his now 13-year-old bride. Lilienblum soon began to study the scriptures and works of Jewish interpretation independently, in which he found nourishment for his burgeoning rationalist attitude.

When his parents-in-law's maintenance ran out in 1865, he took over the management of the yeshiveh. He also won a sponsor whose children he taught to support him regularly. As a result of his own studies and triggered by the secular orientation of his patron, Lilienblum increasingly came into conflict with the views and ideas that were internalized at an early age. Gradually he moved away from rabbinic Judaism, read the writings of the Maskilim , especially Mapu and Mordechai Aharon Ginzburg , and alienated himself from the world of his origins, which had become too narrow for him, from old-style Jewish learning, thought he recognized ignorance and superstition, against which he wanted to fight from now on.

He saw the need for Jewish reform and a harmonious connection between religion and (practical) life. Together with other young men he founded a library in order to enable readers to find the truth in his rationalistic sense through books that were avoided in traditional synagogue communities. Opponents soon see him as heretical, and his mother-in-law, who saw herself as deceived in him, encouraged him. But instead of being intimidated, Lilienblum turned his concern to the public.

Since Lilienblum had never been registered as a Russian subject, he lived as a sans-papier in his own country, which, as a Jew, deprived him of both tsarist discrimination in settling (see Pale of Settlement ) and the dreaded military service, but at the price of legal nothing to be, he chose the family name Herlichstsohn as the author , his idiosyncratic Germanization of the patronymic, based on the Yiddish father's name Hirsch .

His first article ארחות התלמוד(Orchōt haTalmūd, for example: way, ways of the Talmud ) appeared in HaMelīz in 1868 and was respectful of learned orthodoxy, especially hoping for a change in the attitude of rabbis. He was ignored, only two rabbis responded, Chaim Joseph Sikaler from Mogilew-Podolsk approving, and Zvi Finkelstein, who condemned Lilienblum as dangerous. In the meantime, the Yeschivehbocherim often left his educational institution under pressure from their parents and financiers, which angry Jews from Wilkomir eventually destroyed.

Lilienblum traveled to Kedahnen with no income and no opportunity to work, in order to have himself officially registered by the synagogue community of his birth - as was planned in the Russian Empire at the time - for which he chose Herlichstsohn as his family name. The community refused to give him this patronymic name, they would only register him with a different name and so he chose Lilienblum .

Five months after his first article, he turned to נוספות להמאמר ארחות התלמוד(Nōssafōt laMa'amar Orchōt haTalmūd, for example: Addendum to the article 'Orchōt haTalmūd') again via HaMelīz to the public, for the first time under the new name. In it he tackled his opponents directly, to free himself from the paralysis against which he was polemicized as a mere Pilpul and to find the creative will of the early sages of the Talmud in order to develop a new equivalent for the Shulchan Aruch , the demands of the life of his time Takes into account what Lilienblum triggered a storm of indignation.

He was condemned and attacked as a "free thinker", his wife, three children, his mother-in-law as well as his father were cut and shunned, so that Lilienblum had to leave Wilkomir and after months of short stays in different places to Odessa, a center of the Haskala , went (1869) to prepare for university studies. Jews from Kaunas , Maskilim, and their synagogue community stood up for him and warned against repression.

In Odessa he was confronted with the anonymity of the city, felt isolated and suffered from the separation from his family and the woman he loved, Feyge Nowachowicz, who had also stayed in Wilkomir. From his meager salaries as an office worker and tutor, he supported his wife and children. He continued to speak publicly. Lilienblum, for example, opposed marrying children before they were adults and could even learn a profession that would enable them to support a family. In Odessa Lilienblum lost his faith in the divine origin of the Thorah and began to read Russian socially critical authors such as Dmitri Pissarew and Nikolai Tschernyshevsky .

The pogroms against the Jews in Russia in 1878/1881 made him realize the futility of Jewish assimilation. For him the rebirth of the Jewish people in Palestine was the (only) necessary solution to the Jewish question. Together with Leon Pinsker and others, the Palestinophile idea became the Chovevej Zion collection movement - starting from Odessa ( Odessa committee with Lilienblum as secretary and Pinsker as president) - which was developed in the Katowice Conference in 1884 (cf. Max E. . Almond stem ) reached its first culmination point.

In the following years, Lilienblum pursued the development of the Chovevej Zion movement with energy and no small success, but no longer emerged in political Zionism, instead devoting himself more to his (especially literary) historical-philosophical and dramatic writing (in Hebrew and Yiddish).

Works (small selection)

- Autobiography ( chattat ne'urim , "Jugendsünde", Vienna 1876; derech teschuwa , " Umkehr ", Warsaw 1899)

- Collected works (Hebrew), 4 volumes, 1910 ff.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Israel Zinberg (ישראל צינבערגYisro'el Tsinberg; 1873–1938), A history of Jewish literature engl. [yidd. originalדי געשיכטע פֿון דער ליטעראַטור בײַ ייִדן (Di Geshikhṭe fun der Liṭeraṭur bay Yidn), 1st edition 1929–1966]: 12 vols., Bernard Martin (trans.), Vol. 12 'Haskalah at its zenith' (1978; די בלי-תקופה פֿון דער השכלה, Di Bli-tḳufe fun der Haśkole; 1st edition as vol. 13 1966 posthumously), p. 210. ISBN 0-87068-476-0 .

- ↑ From his attitude as a rationalist, which he later acquired, he draws his uncle to have put nonsense about man seducing demons à la Lilith and other superstitions in his head. See Israel Zinberg, A history of Jewish literature engl. [yidd. originalדי געשיכטע פֿון דער ליטעראַטור בײַ ייִדן (Di Geshikhṭe fun der Liṭeraṭur bay Yidn), 1st edition 1929–1966]: 12 vols., Bernard Martin (trans.), Vol. 12 'Haskalah at its zenith' (1978; די בלי-תקופה פֿון דער השכלה, Di Bli-tḳufe fun der Haśkole; 1st edition as Vol. 13 1966 posthumously), p. 210seq. ISBN 0-87068-476-0 .

- ^ Israel Zinberg (ישראל צינבערגYisro'el Tsinberg; 1873–1938), A history of Jewish literature engl. [yidd. originalדי געשיכטע פֿון דער ליטעראַטור בײַ ייִדן (Di Geshikhṭe fun der Liṭeraṭur bay Yidn), 1st edition 1929–1966]: 12 vols., Bernard Martin (trans.), Vol. 12 'Haskalah at its zenith' (1978; די בלי-תקופה פֿון דער השכלה, Di Bli-tḳufe fun der Haśkole; 1st edition as vol. 13 1966 posthumous), p. 211. ISBN 0-87068-476-0 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Israel Zinberg (ישראל צינבערגYisro'el Tsinberg; 1873–1938), A history of Jewish literature engl. [yidd. originalדי געשיכטע פֿון דער ליטעראַטור בײַ ייִדן (Di Geshikhṭe fun der Liṭeraṭur bay Yidn), 1st edition 1929–1966]: 12 vols., Bernard Martin (trans.), Vol. 12 'Haskalah at its zenith' (1978; די בלי-תקופה פֿון דער השכלה, Di Bli-tḳufe fun der Haśkole; 1st edition as vol. 13 1966 posthumously), p. 214. ISBN 0-87068-476-0 .

- ^ Israel Zinberg (ישראל צינבערגYisro'el Tsinberg; 1873–1938), A history of Jewish literature engl. [yidd. originalדי געשיכטע פֿון דער ליטעראַטור בײַ ייִדן (Di Geshikhṭe fun der Liṭeraṭur bay Yidn), 1st edition 1929–1966]: 12 vols., Bernard Martin (trans.), Vol. 12 'Haskalah at its zenith' (1978; די בלי-תקופה פֿון דער השכלה, Di Bli-tḳufe fun der Haśkole; 1st edition as vol. 13 1966 posthumously), footnote 35 on p. 214. ISBN 0-87068-476-0 .

- ^ Israel Zinberg (ישראל צינבערגYisro'el Tsinberg; 1873–1938), A history of Jewish literature engl. [yidd. originalדי געשיכטע פֿון דער ליטעראַטור בײַ ייִדן (Di Geshikhṭe fun der Liṭeraṭur bay Yidn), 1st edition 1929–1966]: 12 vols., Bernard Martin (trans.), Vol. 12 'Haskalah at its zenith' (1978; די בלי-תקופה פֿון דער השכלה, Di Bli-tḳufe fun der Haśkole; 1st edition as Vol. 13 1966 posthumously), p. 214seq. ISBN 0-87068-476-0 .

- ↑ a b c d Israel Zinberg (ישראל צינבערגYisro'el Tsinberg; 1873–1938), A history of Jewish literature engl. [yidd. originalדי געשיכטע פֿון דער ליטעראַטור בײַ ייִדן (Di Geshikhṭe fun der Liṭeraṭur bay Yidn), 1st edition 1929–1966]: 12 vols., Bernard Martin (trans.), Vol. 12 'Haskalah at its zenith' (1978; די בלי-תקופה פֿון דער השכלה, Di Bli-tḳufe fun der Haśkole; 1st edition as vol. 13 1966 posthumously), p. 215. ISBN 0-87068-476-0 .

- ↑ a b Israel Zinberg (ישראל צינבערגYisro'el Tsinberg; 1873–1938), A history of Jewish literature engl. [yidd. originalדי געשיכטע פֿון דער ליטעראַטור בײַ ייִדן (Di Geshikhṭe fun der Liṭeraṭur bay Yidn), 1st edition 1929–1966]: 12 vols., Bernard Martin (trans.), Vol. 12 'Haskalah at its zenith' (1978; די בלי-תקופה פֿון דער השכלה, Di Bli-tḳufe fun der Haśkole; 1st edition as Vol. 13 1966 posthumously), p. 216seq. ISBN 0-87068-476-0 .

- ↑ a b c Israel Zinberg (ישראל צינבערגYisro'el Tsinberg; 1873–1938), A history of Jewish literature engl. [yidd. originalדי געשיכטע פֿון דער ליטעראַטור בײַ ייִדן (Di Geshikhṭe fun der Liṭeraṭur bay Yidn), 1st edition 1929–1966]: 12 vols., Bernard Martin (trans.), Vol. 12 'Haskalah at its zenith' (1978; די בלי-תקופה פֿון דער השכלה, Di Bli-tḳufe fun der Haśkole; 1st edition as vol. 13 1966 posthumous), p. 219. ISBN 0-87068-476-0 .

- ↑ a b c Israel Bartal (ישראל ברטל), "Lilienblum, Mosheh Leib" (entry) , Jeffrey Green (ex.), In: The Yivo Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe , accessed May 17, 2018.

- ^ Israel Zinberg (ישראל צינבערגYisro'el Tsinberg; 1873–1938), A history of Jewish literature engl. [yidd. originalדי געשיכטע פֿון דער ליטעראַטור בײַ ייִדן (Di Geshikhṭe fun der Liṭeraṭur bay Yidn), 1st edition 1929–1966]: 12 vols., Bernard Martin (trans.), Vol. 12 'Haskalah at its zenith' (1978; די בלי-תקופה פֿון דער השכלה, Di Bli-tḳufe fun der Haśkole; 1st edition as vol. 13 1966 posthumous), p. 224. ISBN 0-87068-476-0 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lilienblum, Moshe Leib |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Lily flower, Mose Löb; Lily flower, Moses; Lilienblum, Moses; Bar-Chushim, Zelaphchad (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Hebrew writer, co-founder of Chowewe Zion |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 22, 1843 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Kedahnen , Russian governorate Kovno (now Lithuania ) |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 12, 1910 |

| Place of death | Odessa |