My Kinsman, Major Molineux

My Kinsman, Major Molineux is a short story by the American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne from 1828/29, first published anonymously in Samuel Goodrich's literary almanac The Token in 1832 and included twenty years later in the anthology The Snow-Image and Other Twice-Told Tales . This early history of Hawthorne received little attention in the period that followed until the middle of the 20th century; since its rediscovery in the 1950s, however, it has been one of the most widely interpreted and anthologized narratives in American literature. A German translation by Lore Krüger was published in 1980 under the title Mein Verwandter, der Major Molineux .

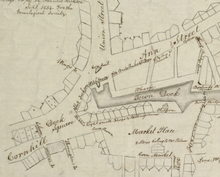

The protagonist of the story, an impoverished country boy, comes to a strange, mysterious city on a summer night to visit an influential relative. During the arduous search for his relative, he is repeatedly and incomprehensibly rejected in various encounters with residents of this city, which can be recognized as Boston in historical detail . Overtired and confused, he finally experiences a mixture of dream and reality as his relative is tarred and sprung on a cart and mocked. Initially full of pity and horror, the youngster then joins the scornful laughter of the mob in a state of confusing excitement.

content

My Kinsman begins with a historiographical introduction that provides the historical background and dates the event to around 1730. In the historical frame of reference presented, the narrator points out the increasing tensions between the governors of the English crown and the people in the American colonies, which repeatedly led to violent riots against the English governors.

The story then tells of the almost eighteen-year-old Robin, who is transported to Boston by an unfriendly ferryman as the only passenger on a moonlit summer evening. The driver can pay a special fee for the crossing at this unusual time. The boy is dressed in a well-worn gray coat and an old three-cornered hat on his head; He keeps his few belongings in a satchel on his back and in his left hand he holds a heavy oak club for protection.

As the youngest son of a poor pastor's family, Robin came to the city from the country to visit his wealthy relative, the childless Major Molineux, and to make his fortune with his support, which he had previously offered to his relatives. While searching for his uncle's house, the newcomer strangely comes across mockery and mocking laughter when he asks for directions.

An old man with a polished stick, furious and annoyed, threatened to punish him the next morning by pointing out his authority; two barber boys, watching the incident with interest, respond with raw laughter. An innkeeper, who greets him warmly at first, accuses him of being a runaway servant to the general laughter of the guests present and promises a reward to those who put him in one of the provincial prisons. A lying prostitute in a scarlet petticoat tries to lure him into her house with the false claim that she is the major's housekeeper; a night watchman chases him off the street with another threat of punishment. A small group of men speak in a language that Robin does not understand and, like the night watchman, owes him the answer to his question about the way to the major's apartment. A mysterious stranger with fiery eyes, a double bulge on his forehead and a black and red infernal face prophesies that the major will soon arrive.

When Robin looks through the window of an abandoned church, he sees the open pages of a large Bible in the moonlight. In a dreamlike imagination, he sees his family who have gathered in front of the house under a tree for a common prayer and meanwhile thinks of him and misses him. After the prayer, however, his sister locks the front door before Robin can follow the family into the house. He feels lonely and excluded.

Shortly afterwards, a friendly stranger joins him on the stairs and keeps him company. The stranger to whom Robin reports his concern is confident that Major Molineux will be over in a few minutes. Robin's attention is drawn to a noisy crowd, led by a militarily clad rider with a drawn sword, approaching in a bright red glow of moonbeams and torches with the blaring of trumpets. The grim, piebald appearance of the leader with his martial colored red-black face and the wild figures that follow him in Indian guise give the march an unreal, fabulous look like in a feverish dream.

Amid the shouts and laughter of the crowd, a cart is pulled up on which Robin's uncle sits, tarred and sprung. Despite the physical pain and the unbearable humiliation of the abuse of the crowd, Major Molineux, whose tall, majestic figure testifies to his steadfastness, tries to suppress the tremors and tremors of his body in order to preserve his pride and dignity. When the boy's gaze meets him, it seems to cause him the greatest agony.

Robin is initially full of pity and horror; however, the ghostly situation and, more than anything else, the realization of the ridiculousness of the whole scene soon arouse a bewildering excitement in him and send him into a kind of mental drunkenness. In his confusion he hears the roaring laughter of the crowd and notices the people he has met before. The infectious laughter grips Robin; he laughs roaring, the loudest of all, so that it roars through the streets.

After the spook is over, the disturbed Robin wants to return home and asks the friendly stranger for directions to the ferry. However, he advises him to stay and to make his way into the world without the help of Major Molineux.

Work context and significance in literary history

After completing his training at Bowdoin College in Maine and returning to Salem , Hawthorne turned to writing from 1825, but was with his first literary attempts, the brief romance Fanshave (1828) and the first collection of short stories Seven Tales of My Native Land so dissatisfied that he destroyed all of the manuscripts. From 1830 onwards, however, various historical sketches and allegorical stories by Hawthorne about life in colonial New England appear anonymously in New England magazines, newspapers and gift volumes.

My Kinsman, Major Molineux belongs to this group of early stories by Hawthorne, which were probably written around 1828/29. The short story was first published anonymously in 1832 in the Boston almanac The Token by Samuel Griswold Goodrich, sold as a gift ribbon, under the title My Uncle Molineux ; only "the author of" Sights from a Steeple "" was named as the author . Contemporary readers and critics were obviously unimpressed with the narrative; the only surviving comments on the publication of the story in The Token are found in Goodrich's remarks in his letters to Hawthorne.

Hawthorne himself evidently did not at first seem to attach any great importance to the story; in 1837 when he published various of his scattered early stories as an anthology entitled Twice Told Tales under his own name, he renounced a recording of My Kinsman, Major Molineux . It was not until two decades after it was first published that Hawthorne included the story in his anthology The Snow-Image and other Twice Told Tales in 1852 , without, however, attracting much attention from contemporary readers, critics or authors. In one of the few surviving reviews of The Snow Image , EA Duyckinck expressed disapproval of My Kinsman, Major Molineux in 1852 and criticized the image of the tarred and feathered appearance of Robin's relatives as an extremely lame and ineffective conclusion ( "Most lame and impotent conclusion") ). Only Hawthorne's former classmate at Bowdoin College , the writer and poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow casually mentions in his Tales of a Wayward Inn (1863–1874, collected in 1886) “the great Major Molineux, / Whom Hawthorne has immortal made” (Eng. “Den great Major Molineux, whom Hawthorne immortalized ”), for which Hawthorne thanked profusely.

Even after Hawthorne's death in 1864, My Kinsman, Major Molineux, like many of his other stories, remained largely unnoticed for decades. The author was widely dismissed as being too allegorical; In 1937, Yvor Winters disdainfully described Hawthorne's stories as "at best slight performances" .

This assessment of My Kinsman, Major Molineux only fundamentally changed with the inclusion of the story in the anthology The Portable Hawthorne edited by Malcolm Cowley in 1948 and the publication in 1951 of QD Leavis' work "Hawthorne as Poet" , in which the disdain for the stories Hawthorne was criticized in literary studies and criticism as extremely in need of revision. Leavis made explicit reference to My Kinsman and stated that Hawthorne had nowhere else in this narrative "with regard to dramatic creative power, in the mastery of tone, speed and tension, [...] in the creation of tension between the fullest consciousness the meaning and emotional incoherence of dreaming ”( “ Hawthorne never anywhere surpassed this tale […] in dramatic power, in control of tone, pace, and tension, and in something more wonderful, the creation of suspense between the fullest consciousness of meaning and the emotional incoherence of dreaming ” ).

This reassessment of My Kinsman, Major Molineux moved the hitherto almost unknown story into the field of view of literary scholars and critics and subsequently led to a wealth of over eighty interpretations, some of which were controversial. To this day, My Kinsman is one of the most widely interpreted and anthologized short stories in American literature. Despite the contradicting interpretations and readings, My Kinsman, Major Molineux is now almost unanimously not only one of the most successful and impressive stories from Hawthorne, but also one of the most beautiful American short stories ( "one of the finest short stories in the language" ). A play of the same name by Robert Lowell , based on Hawthorne's story, premiered in New York in 1964 with great success.

In terms of literary history, My Kinsman, Major Molineux, along with Young Goodman Brown, is also one of the first representative or constitutive examples of the development of the new subgenre of initiation history in American short prose.

Interpretations and readings

Ambiguity of the text statements

The American literary scholar and Hawthorne specialist Hyatt H. Wagoner stated in 1971, with regard to My Kinsman, Major Molineux, the obvious impossibility, the complexity, ambiguity and openness of this narrative with its numerous coexistence and confused levels of meaning in a comprehensive and coherent literary critical interpretation or Merge reading. So he drew the conclusion in a rather resigned tone: Any criticism is likely to seem heavy-handed when dealing with this story ("Any criticism will probably appear awkward or clumsy when dealing with this story ").

The renowned Americanist Peter Freese , on the other hand, sees the irony, pardoxy and ambiguity of this long-neglected narrative with its broad, open meaning potential and immense wealth of references as an essential reason why My Kinsman is rediscovered by readers, interpreters and critics as "extremely modern" could be. With their ambiguous typological references and analogies to the "rites of national passage" , according to Freese, "central questions about the American self-image" are raised; in the extremely complicated historical significance layer, a critical attitude Hawthorne, considered the winning of American independence as a "linked with moral inadequacy and human error happening" and also in the indirect confrontation Hawthorne with the success ethic Benjamin Franklin realization possibilities of articulating American dream with probing doubt. In addition, the impressively designed loneliness of the youth from the country in the confusing city with its isolation and isolation offers a variety of the own alienation of the Hawthorn protagonist, with which today's readers can probably still identify. According to Freese, Robin's dramatic confrontation with the shattering world of his fathers, in its ambiguity, also symbolizes a generation conflict; Through the numerous allegorical references to timeless basic patterns of archetypal cultural developments and processes in My Kinsman , the individual occurrence is also exaggerated into a timeless occurrence, which creates opportunities to create meaning even in today's increasingly "fragmented or meaningless world". In particular, the disillusioning movement from “naive innocence on the paradisiacal land to the painful experience in the labyrinthine city” proves to be “infinitely complex and ambiguous”, at the same time timeless and current “representation of fundamental internal and interpersonal conflicts”.

Different interpretive approaches in the history of reception

The multi-layered wealth of references and the bundle of themes and possible meanings created in My Kinsman led to different, sometimes contradicting, sometimes overlapping and complementary attempts at interpretation in the complex history of the reception of the work, which, from a systematic point of view, are essentially historical-political, mythological-allegorical, allow psychological and moral-theological approaches to interpretation to be summarized.

Historical-political interpretations

The historiographical introduction embeds the narrative in the historical context of pre-revolutionary Boston. Reference is expressly made to the "kings of England" who "had assumed the right to appoint the governors of the colonies". It also addresses the resulting tensions with the New England people after the reign of James II "until the revolution" recorded in the "Annals of Massachusetts Bay".

Against the background of this historical frame of reference, QD Leavis provided Hawthorne's story with the subtitle “America comes of Age” in 1951 and attempted to portray the nocturnal events as a historically and politically complex poetic parable ( “poetic parable " ), which is about the achievement of American national independence and the price to be paid for it ( " [...] a dramatic precipitation of, or prophetic forecast of the rejection of England that was to occur in fact much later " ). The naive but self-assured Robin personifies the freedom-seeking America, while the reviled and humiliated Major Molineux symbolizes the end of English colonial rule. Robin's painful experience also shows that the newly won freedom cannot be won without guilt or the painful loss of innocence.

This interpretation, in which My Kinsman is understood as a fictional confrontation with American history, which seeks to explore the shaping of the present by the past, was taken up again in 1954 by Roy Harvey Pearce from a different perspective. According to him, the central theme of the story is "the imputation simultaneously of guilt and righteousness through history" (English: "the simultaneous attribution of guilt and righteousness through history"). Hawthorne wanted to express with his story above all that the political and social history of America is burdened by original sin ; Adam's fall and the idea of historical progress are not mythologically separate, but one ( "Original Sin [...] becomes the prime fact of our political and social history. Adam's Fall and the Idea of Progress become not two myths, but one") ). Such an interpretation of Hawthorne's story as “a narrative explanation of a historical phenomenon” as well as a “type” of the American Revolution was taken up and continued several times by other interpreters and critics in the period that followed.

Pearce and other literary scholars also tried to elucidate the historical background in more detail and to make references to the historical figure of the real William Molineux, but without being able to convincingly solve the problem that this Boston merchant, unlike Robin's relatives, was anything but a loyalist . Partly in this line of interpretation at the same time largely speculative references to the historical figure of an Irish lawyer and philosopher of the same name were made, from which the interpretation was derived that for Robin the task of cognition arises “between reason and moderation on the one hand and militancy and excess the other side ”. The German Americanist Hans Joachim Lang extended this range of interpretive approaches in its attempt to show that Hawthorne's story a network of hidden clues to the United States presidential election, 1828 contained and the two-faced man in relation to the seventh US president Andrew Jackson could be brought .

Myth-critical and allegorical interpretations

The common premise of the historical interpretive approaches that Hawthorne's story deals with the most important political and cultural theme of the American republic , national self-determination and its consequences, was taken up by Daniel G. Hoffman in 1961, but his interpretation was taken on an inflated mythical - allegorical level relocated. Already in Leavis, who in the confrontation between Robin and his humiliated uncle believed she recognized the submission of the old king by a new one, there is a close interweaving of historical and myth-critical interpretations.

Against the background of the increasing influence of a literary critical school in the 1960s, which primarily tried to trace literary texts back to archetypal processes or basic mythical patterns, Daniel G. Hoffman sees in My Kinsman above all the colonial re-staging of the old ritual of the deposition of the scapegoat king ( "An eighteenth-century colonial re-enactment of the ancient ritual of the deposition of the Scapegoat-King" ). The historical development from British colonial rule to national independence , which is thematized in the story, is understood in this reading as the historical-allegorical concretization of a timeless archetype; the tarred and feathered Major Molineux embodies the "Sacrificed King, the Royal Scapegoat" (Eng. the sacrificed king, the royal scapegoat ), as he is described in Frazer's study of magic and religion The Golden Bough . According to this interpretation, the ritual deposition ceremony archetypically fulfills a double function: the vicariously personified evil is expelled and the sacrificial death of the old divine ruler, whose strength has waned, leads to a renewal of power through the appointment of his young successor. According to this understanding, the conspirators in Hawthorne's story eliminate the main evil in the colony with the sacrifice of Major Molineux as a scapegoat; Evidence is seen, among other things, in the fact that the midsummer night scene shown is linked in the story with the ritual features of May celebrations. The double-faced leader is understood in these interpretive approaches as a representative of anarchy, chaos and disorder ( riot and disorder ), as Lord of the Misrule , whose rule is only a "mock reign" , the ritual of the restoration of a new, ( "serve the end of re-establishing a stable order based on institutions more just than those overthrown." ). In this context of interpretation, reference was also made to the obvious allusions in Robin's name and in the design of the dreamy nocturnal scenery to Shakespeare's comedy A Midsummer Night's Dream ; like Robin Goodfellow alias Puck in Shakespeare, the wise ( "shrewd" ) Robin embodies the archetypal rebellion against authority.

This mythological interpretation approach presented by Hoffman was expanded in various aspects in the following years. In addition, reference was made in particular to the archetypal pattern of the search and nocturnal journey from innocence to destructive knowledge ( "unadorned archetypal pattern of the journey from innocence into destructive knowledge" ) as well as Robin's crossing on the ferry, which allegorically refers to the crossing of the Styx remembered in Greek mythology.

The numerous other contributions in this direction, a mythological interpretation of Hawthorne's narrative, with often far-fetched, mostly speculative conclusions, naturally concentrate predominantly on the darker aspects of what happened in the story.

Psychological interpretations

The ambiguous settlement of the story between dream and reality as well as the confrontation of a confused young person with the world of their fathers also offer starting points for a psychological or psychoanalytically oriented literary interpretation .

As early as 1955, Simon O. Lesser called for the inclusion of psychoanalytic patterns of interpretation in the interpretation of the narrative in order to sound out the manifest narrative content in terms of its deeper or latent meaning. He saw My Kinsman as a characteristic embodiment of oedipal conflicts in the Freudian sense and put forward the thesis that Robin unconsciously searches for sexual adventures in order to free himself from his child-like dependency as a son from the dominance of the adult world in adolescence ( “free of adult domination " ). As a reason, Lesser explains that although Robin is looking for the major on the conscious level, an opposite pattern can be seen on the subconscious level; In truth, Robin didn't want to meet the major at all. So he “forgot” to ask the ferryman for directions, was in no hurry to get to the major's house, lingered in the squares and in front of the shops for a long time, let the time pass, was not averse to the obvious lies Believing the prostitute with her sweet voice and narrow waist in the scarlet underskirt and in spite of the numerous rejections did not intensify his search for the major's apartment.

In this perspective, Robin is the rebellious adolescent who, on the run from fatherly authority and in search of sexual freedom, rebels against his uncle as a symbol of oppression and authority. The turmoil in the whole city encourages him to give in to his long repressed, secret desires; In this interpretation, his rebellion reaches its climax in his attunement to the wild laughter of the crowd, which for him in a kind of catharsis becomes a liberating laugh, since he no longer has to suppress the unconscious hostility towards his relative and can give up the search for him ( "The relief he feels that he can vent his hostility for his kinsman and abandon his search for him [...] buried hunger to break loose of a childlike dependence on patriarchical guides [...] cathartically rid himself of both filial dependence and filial resentment " ). The repeated threat of punishment is given additional weight in such an interpretative perspective; The many references to sticks from Robin's heavy “oak club” (p. 104) to the old man's “long, shiny walking stick” (p. 105) can also be understood as phallic symbols in this reading .

Based on Sartre and Laing , an attempt was also made to interpret Robin's figure as a symbol of a person painfully confronted with ontological uncertainty in an existential psychological analysis . According to Freese, however, this interpretation remained largely speculative.

Moral-theological interpretations

While the question of Robin's individual responsibility does not arise in the historical, archetypal and psychological interpretations, or at best plays a marginal role, another group of interpretations tries to direct the view of the moral implications of Robin's behavior and development.

Like Seymour L. Gross, one understands Robin's odyssey as a moral allegory and his odyssey as a “journey from the innocence of an original paradise into the scorching fire of satanic knowledge” ( “the voyage from the blind innocence of a primal paradise to the scorching fire of satanic knowledge ” ), then the dark city with its labyrinthine tangle of narrow streets (p. 107) appears as a symbol of human guilt. The man with the two-tone black and red face becomes the epitome of Dante 's Satan; Robin's laughter no longer represents an act of liberation, but rather expresses his bitter self-contempt for his moral failure after learning to distinguish good and bad. By denying his relatives he did evil himself and now knows that he will never return to the paradisiacal world of innocence. In such an interpretation, the story thematizes the connection between guilt and maturity, in which Robin's loss is much greater than his gain.

My Kinsman can accordingly be understood as “a brutally realistic account of human viciousness” ; Arthur T. Broes sees Hawthorne's central statement in the fact that sooner or later, as a result of the fall, man must inevitably get to know evil ( “[...] in the language of symbol and allegory, that man, as a result of the fall , cannot remain in the state of innocence [...] but must sooner or later come to a knowledge of evil " ); In other analyzes too, the gloom of the moral statement is emphasized in this context of interpretation. The various references made by the narrator to Robin's cleverness ( "shrewdness" ), ironized in the respective contexts, can be interpreted in this respect as signs of his arrogance; the use of the term "shrewd" in the friendly stranger's closing remarks would either be understood as an ironic reference to Robin's moral depravity or should be taken seriously as a signal that Robin has now gained insight and that the path for his further growth is too spiritual -Moral maturity is open. Against this background, Hawthorne's statement could be interpreted as meaning that self-determination and personal responsibility can only be achieved after encountering evil and confronting one's own failure.

If My Kinsman is understood as a moral allegory, the seven encounters between Robin and the people of the city, echoing Dante's Inferno (1307–1321), Bunyan's Vanity Fair (1678) and Spenser's Fairie Queen (1590–1596), can also be seen as the conflict comprehend the protagonist with the personified seven deadly or capital sins; even the friendly stranger could be understood in this frame of reference as “a devil's advocate” . His advice to Robin in the end to stay in the city despite the painful disillusionment would then ironically amount to an “invitation to spiritual ruin” (German: “invitation to spiritual and moral downfall”).

Ironic reversal of Franklin's ethics of success

At the likely time My Kinsman, Major Molineux was written, in the fall of 1828, Hawthorne had borrowed the first five volumes of Benjamin Franklin's Works from the Salem library. In several literary analyzes, the strikingly close parallels between Hawthorne's story and the famous passage from Franklin's autobiography , in which the latter reports on his arrival in Philadelphia, have been examined in more detail. This passage from Franklin's autobiography in turn formed the archetypal basis for countless narrative realizations of the American Dream , which found their most popular expression in the "from rags to riches" stories of Horatio Alger .

Due to the numerous unmistakable similarities and correspondences in many details, it is very likely that there is a direct connection between Hawthorne's story and Franklin's report of his arrival in Philadelphia; possibly Robin's name not only alludes to the Shakespearean Robbin Goodfellow / Puck , but also refers to the almanac Poor Robin published by Franklin's brother James and thus indirectly to Franklin's positions in Poor Richard's Almanack .

More striking than the similarities and similarities, however, are the differences, which suggest a critical reversal of worldview from Franklin's autobiography. If the beginning of Franklin's astonishing ascent is illuminated by daylight upon his arrival in Philadelphia, that at Hawthorne is contrasted by the nocturnal wandering of the unsuccessful Robin Molineux. Likewise, Franklin's “calm in the peaceful meeting room of the deist Quakers ” is contrasted with Robin's agonizing loneliness in front of the church of a “revenging Puritan God”. Young Benjamin receives friendly help and support; Robin, on the other hand, is met with sneering rejection and threats of punishment. Hawthorne contrasts the clever and naive Ben with the naive and only clever Robin.

Accordingly, Hawthorne's story represents an “ironic-pessimistic counterfacture to Franklin's ethics of success, which has been criticized as ostensibly optimistic”. The story thus becomes an “early symbolization of the nightmarish downside of the American Dream ” and can be understood as a political parable in which Hawthorne “inadequacy and failure diagnosed as part of the very early days of the nation ”. In this regard, Hawthorne already articulates the fundamental doubts about the myth of success, which have now become a more or less consistent characteristic of recent American literature.

“My Kinsman” as an initiation story

In numerous literary studies, My Kinsman, Major Molineux is explicitly classified as a story of initiation or implicitly understood as such. With regard to the characteristic features and typical constituents of a story of initiation , the story describes the first journey of an adolescent as a visit by Robin, the inexperienced or innocent boy from the country, to a city that is strange to him. For the youthful hero, the various stations of the journey are realized as a series of confrontations, at the end of which Robin gains an insight or insight that is decisive for him.

The pattern of an initiation story also corresponds to the narrative technical design with central individual elements such as the history of pulling through laughter, the symbolic interplay of light and darkness or of natural and artificial light, the symbolic imagery of houses and streets as well as the highlighted theme of wisdom ( shrewdness ). In addition, the narrative contains an abundance of motif-symbolic pairs of opposites typical for initiation, such as nature and civilization, city and country, authenticity and artificiality, order and disorder, existence and appearance, dependency and independence, togetherness or security and isolation or insecurity, as well as ignorance and knowledge. In an equally characteristic way, the story is presented in the basic form of a three-part structure, in which the essential steps from childhood to adulthood are symbolized as a life journey with an exit from the old, a transition and finally an entry into the new mode of existence .

Depending on the reading, the events in the short story can either be historically understood as three steps from colonial dependency or monarchy through the uprising or revolt to national independence or democracy or, critically, as " the hero's quest from a sunlit land of ordinaryity to just one The nocturnal darkness of the city that can be reached across the river, in which the last thing to do is to acquire knowledge of good or bad. Nor does a psychoanalytic understanding of history contradict a classification as a history of initiation. Here, too, a three-part structure emerges as the development from the dependent child through the rebellion of the rebellious adolescent against paternal authority and the subsequent entry into self-determined adult life. In the moral theological sense, the threefold nature of the narrative can be represented as the development of paradisiacal innocence through the fall of man of knowledge to participation in human guilt.

Regardless of the way in which the initiation or the topic of initiation is understood, My Kinsman contains a variation on the different levels of meaning of the development from innocence to experience, which is characteristic of the American story of initiation (Eng .: "from innocence to experience") . However, even such an interpretation pattern as an initiation story cannot completely resolve the fundamental ambiguity of the text; At the end of the story, the question remains whether Robin actually gained a new knowledge or insight or whether he is closed to further development.

literature

Expenses (selection)

The modern standard edition of Hawthorne's works is The Centenary Edition of the Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne (edited by William Charvat, Roy Harvey Pearce et al., Ohio State University Press, Columbus OH 1962-1997; 23 volumes). My Kinsman, Major Molineux can be found in Volume XI ( The Snow-Image and Uncollected Tales , 1974). Various edited volumes of Hawthorne's short stories include My Kinsman, Major Molineux , for example in paperback

- Nathaniel Hawthorne: Selected Tales and Sketches. (= Penguin Classics ). ed. by Michael J. Colacurcio , Penguin Books, New York 1987, ISBN 1-101-07780-8 .

In the German-speaking countries an edited text edition of My Kinsman, Major Molineux is also published in:

- Peter Freese (Ed.): The American Short Story I: Initiation · Texts for English and American Studies . Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn 1984, ISBN 3-506-41083-0 , pp. 8-28.

There are two translations into German:

- My relative, Major Molineux . German by Lore Krüger . In: Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Black Veil and Other Selected Stories . Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1980, ISBN 3-538-06584-5 .

-

My relative, Major Molineux . German by Hannelore Neves. In: Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Heavenly Railroad. Stories, sketches, forewords, reviews . With an afterword and comments by Hans-Joachim Lang . Winkler, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-538-06068-1 .

- Also in: Nathaniel Hawthorne: Eerie Tales . Edited by Siegfried Schmitz. Transferred from the American by Hannelore Neves and Siegfried Schmitz. Albatros Verlag, Düsseldorf 2007, ISBN 978-3-491-96208-8 (new edition)

Secondary literature (selection)

- Peter Freese : On Difficulties in Growing Up: American Stories of Initiation from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Joyce Carol Oates - Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux". (1832). In: Peter Freese, Horst Groene, Lisel Hermes (Eds.): The Short Story in English Lessons at Secondary Level II - Theory and Practice. Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn 1979, ISBN 3-506-74073-3 , pp. 209-220.

- Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives: On the reception story of Nathaniel Hawthorne's "My Kinsman, Major Molineux". In: Klaus Lubbers (ed.): The English and American short story. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1990, ISBN 3-534-05386-9 , pp. 12-27. Reprinted in: Peter Freese: The American Short Story - The American Short Story · Collected Essays . Langenscheidt-Longman Verlag, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-526-50864-X , pp. 160-175.

- Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". In: Peter Freese: The American Short Story I: Initiation - Interpretations and Suggestions for Teaching . Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn 1986, ISBN 3-506-41084-9 , pp. 89-158.

- Seymour L. Gross : Hawthorne's 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux': History as Moral Adventure. In: Nineteenth-Century Fiction. 12 (1957/58), pp. 97-109.

- John V. Hagopian: My Kinsman, Major Molineux. In: John V. Hagopian, Martin Dolch (Eds.): Insight I - Analyzes of American Literature . Hirschgraben Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1971, DNB 740160826 , pp. 69-73.

- Daniel G. Hoffman: Yankee Bumpkin and Scapegoat King. In: Sewanee Review. 69, 1961, pp. 48-60. Reprinted in Daniel G. Hoffman: Form and Fable in American Fiction . New edition. University Press of Virginia, London 1994.

- QD Leavis : Hawthorne as Poet. In: Sewanee Review. 59, 1951, pp. 179-205. Reprinted in Charles Feidelson Jr., Paul Brodtkorb Jr. (Eds.): Interpretations of American Literature. New York 1959, pp. 30-50.

- Simon O. Lesser: The Image of the Father: A Reading of 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux' and 'I Want to Know Why'. In: Partisan Review. 22, 1955, pp. 372-390.

- Roy Harvey Pearce : Hawthorne and the Sense of the Past or, The Immortality of Major Molineux. In: Journal of English Literary History. 21, 1954, pp. 327-349.

- Peter Shaw: Fathers, Sons and the Ambiguities of Revolution in 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux'. In: New England Quarterly. 49, 1976, pp. 559-576.

Web links

- Frank Stevenson: Exteriority, Laughter and Comic Sacrifice in Hawthorne's “My Kinsman, Major Molineux” . Article from: Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies , 37.1, March 2011, pp. 169–199, as a PDF file. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- My Kinsman, Major Molineux - A Study Guide . English-language interpretation on: cummingsstudyguides.net . Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- Young Goodman Brown and Other Hawthorne Short Stories - Summary and Analysis . English-language interpretation on: cummingsstudyguides.net . Retrieved October 9, 2014.

Individual evidence

- ↑ See Peter Freese : Robin and his many relatives: On the reception history of Nathaniel Hawthorne's "My Kinsman, Major Molineux". P. 12.

- ↑ There are now over eighty attempts at interpretation. On the history of publication and impact, see Peter Freese in detail: Robin and his many relatives. P. 12 ff. And Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". Pp. 109-125.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Robert C. Grayson: The New England Sources of 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux'. In: American Literature. 54, 1982, pp. 545-559. In his analysis, Grayson shows that the city described in the story reflects the historical reality of Boston around 1730 down to the smallest detail. See also meticulously the depiction of the historical parallels in Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". Pp. 128-132.

- ↑ Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives: On the reception story of Nathaniel Hawthorne's "My Kinsman, Major Molineux". In: Klaus Lubbers (ed.): The English and American short story. P. 14 f.

- ↑ See Peter Freese: Texts 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". P. 89.

- ↑ See Peter Freese: About the difficulties of becoming an adult. P. 209 f., Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". P. 89, and Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives. P. 12.

- ↑ Quoted from Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". P. 90. See also Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives. P. 12.

- ↑ See the information and evidence from Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". P. 90, and Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives. P. 12. Longfellow's quote was taken from these sources.

- ↑ See the information and evidence from Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". P. 90, and Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives. P. 12 f. Winter's quote was taken from these sources. For the context of My Kinsman's work, see also Hans-Joachim Lang : Poeten und Pointen. On the American narrative of the 19th century. (= Erlanger studies. 63). Palm & Enke, Erlangen 1985, p. 83 ff.

- ^ QD Leavis : Hawthorne as Poet. In: Sewanee Review. 59, 1951, pp. 179-205. Reprinted in Charles Feidelson Jr. and Paul Brodtkorb Jr. (eds.): Interpretations of American Literature, New York 1959, pp. 30–50, here p. 46. See also Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne , "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia." P. 90, and Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives. P. 13.

- ^ Hyatt H. Wagoner : The Presence of Hawthorne. Baton Rouge Verlag / Louisiana State University Press, 1979, p. 27.

- ↑ On these aspects of the history of reception, see in detail the information and evidence from Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". P. 90 f., And Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives. P. 13. Similarly, in concise form, John V. Hagopian: My Kinsman, Major Molineux. P. 69. See also Hans-Joachim Lang : Poeten und Pointen. On the American narrative of the 19th century. (= Erlanger studies. 63). Palm & Enke, Erlangen 1985, p. 86.

- ↑ See the information and evidence from Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". P. 90 f. and 132 ff. See also Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives. P. 23 f.

- ^ Hyatt H. Wagoner : Hawthorne. A critical study . Revised Edition. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge Mass. 1971, p. 63.

- ↑ Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives. P. 25 ff. See also more detailed with numerous references to Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia" , here especially pp. 145–149.

- ↑ See my relative, Major Molineux. In: Nathaniel Hawthorne: Eerie Tales. Edited by Siegfried Schmitz, p. 103. In the following, the text is quoted from this edition.

- ↑ See QD Leavis: Hawthorne as Poet. In: Sewanee Review. 59, 1951, pp. 179-205. Reprinted in Charles Feidelson Jr. and Paul Brodtkorb Jr. (eds.): Interpretations of American Literature, New York 1959, pp. 30–50, here especially pp. 44–50. See also the detailed description by Peter Freese on the historical-political approaches: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". Pp. 110–114, and in summary Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives. Pp. 16-18.

- ^ Roy Harvey Pearce : Hawthorne and the Sense of the Past or The Immortality of Major Molineux. In: Journal of English Literary History. 21, 1954, pp. 327-349, here p. 330.

- ↑ See in more detail the description and information in Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives. Pp. 16-18.

- ↑ Pearce's attempt to solve the problem of changing the real Molineux into a loyalist by arguing that Robin is also a Molineux and that he and his uncle are artistically a unit ( "in artistic fact are one ") is difficult as a speculative assumption understand. See Roy Harvey Pearce : Hawthorne and the Sense of the Past or The Immortality of Major Molineux. In: Journal of English Literary History. 21, 1954, p. 329. See also the criticism by Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". P. 110 f.

- ↑ Cf. on this line of interpretation in detail the critical presentation by Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives: On the reception history of Nathaniel Hawthorne's "My Kinsman, Major Molineux". In: Klaus Lubbers (ed.): The English and American short story. P. 16 f., And Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". Pp. 110-114. Freese describes in detail a large number of other philological efforts to create analogies and references to real historical sources.

- ^ Hans Joachim Lang : Biographical and Historical Parallels: Napoleon, Jackson and Hawthornes Robin Molineux. In: Wolfgang Binder (Ed.): Westward Expansion in America (1803-1860) . Palm and Enke Verlag, Erlangen 1987, ISBN 3-7896-0171-3 , pp. 99-126.

- ↑ See QD Leavis : Hawthorne as Poet. P. 49.

- ^ Daniel G. Hoffman: Yankee Bumpkin and Scapegoat King. In: Sewanee Review. 69, 1961, pp. 48-60, here p. 48. The article was also included in Hoffman's book Form and Fable in American Fiction . Oxford University Press, New York 1961 (new edition University Press of Virginia, London 1994) included.

- ^ Daniel G. Hoffman: Yankee Bumpkin and Scapegoat King. P. 53 f., 54 and 59, as well as Peter Shaw: Fathers, Sons and the Ambiguities of Revolution in 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux'. P. 569 f. See also the references from Peter Freese: Texts 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". P. 116 f.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Richard C. Carpenter: Hawthorne's Polar Explorations: 'Young Goodman Brown' and 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux'. In: Nineteenth-Century Fiction. 24, 1969, pp. 45-60, and Peter Shaw: Fathers, Sons and the Ambiguities of Revolution in 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux'. In: New England Quarterly. 49, 1976, pp. 559-576. See the presentation by Peter Freese in more detail with information on evidence: Texts 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". Pp. 114-117.

- ↑ See Peter Freese: Robin and His Many Relatives. P. 18 f.

- ↑ Simon O. Lesser: The Image of the Father: A Reading of 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux' and 'I Want to Know Why'. In: Partisan Review. 22, 1955, pp. 372-390, especially p. 376 ff.

- ↑ Simon O. Lesser: The Image of the Father: A Reading of 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux' and 'I Want to Know Why'. In: Partisan Review. 22, 1955, pp. 372-390, here p. 380. Robert E. Abrahams: The Psychology of Cognition in 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux'. In: Philosophical Quarterly. 58, 1979, pp. 336-347, here p. 342. Frederick C. Crews: The Sins of the Fathers; Hawthorne's Psychological Themes . Oxford University Press, London et al., 1966, p. 78. See also Peter Freese: On Difficulties in Growing Up: American Stories of Initiation from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Joyce Carol Oates. P. 213, and Peter Freese: Texts 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". P. 103.

- ↑ See Peter Freese: On Difficulties in Growing Up: American Stories of Initiation from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Joyce Carol Oates. P. 213. For a criticism of the psychological reading of history cf. Roy Harvey Pearce : Robin Molineux on the Analyst's Couch. In: Criticism. 1, 1959, pp. 83-90. Pearce, on the other hand, takes the polemical view that one can only do justice to Hawthorne's story if Robin is taken from the couch and put back in the story.

- ↑ See Peter Freese: Robin and His Many Relatives. P. 20.

- ^ Seymour L. Gross : Hawthorne's 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux': History as Moral Adventure. In: Nineteenth-Century Fiction. 12 (1957/58), p. 107 f. See also Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives: On the reception story of Nathaniel Hawthorne's "My Kinsman, Major Molineux". P. 20 f.

- ^ Thomas E. Conners: My Kinsman, Major Molineux: A Reading. In: Modern Language Notes. 74, 1959, pp. 299-302, here p. 299.

- ↑ Arthur T. Broes: Journeyinto Moral Darkness: 'My Kinsman' as Allegory. In: Nineteenth-Century Fiction. 19, 1964, pp. 171-184, here bes, p. 180.

- ↑ See, inter alia, B. Thomas E. Conners: 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux': A Reading. In: Modern Language Notes. 74, 1959, pp. 299-302, or Arthur T. Broes: Journey into Moral Darkness: 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux' as Allegory. In: Nineteenth-Century Fiction. 19, 1964, pp. 171-184. See also the summary with further evidence from Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives. P. 20 f. and 215 f., as well as Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". Pp. 120-122.

- ↑ In this reading the ferryman stands for avarice, the old man with the stick for arrogance or pride, the innkeeper for gluttony, the prostitute for lust and the sleepy security guard for laziness or indolence. The remaining vices of anger and envy are rather vaguely attributed to the mob, which deride and ridicule the major. See e.g. B. Arthur T. Broes: Journey into Moral Darkness: 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux' as Allegory. In: Nineteenth-Century Fiction. 19, 1964, pp. 181 and 183. See also Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia" on this approach . Pp. 121 and 124.

- ↑ See Peter Freese: On Difficulties in Growing Up: American Stories of Initiation from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Joyce Carol Oates. P. 218 f.

- ↑ See Peter Freese: On Difficulties in Growing Up: American Stories of Initiation from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Joyce Carol Oates. P. 219 f. At this point Freese shows in his critical comparison of texts the many similarities and direct correspondences between Hawthorne's short story and the passage from Franklin's autobiography; Hawthorne uses a complex pattern of repetitions and variations. See also in detail Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". P. 125 f. A detailed proof of the parallels can also be found in Julian Smith: Coming of Age in America: Young Ben Franklin and Robin Molineux. In: American Quarterly. 17, 1965, pp. 550-558, AB England: Robin Molineux and the Young Ben Franklin: A Reconsideration : In: Journal of American Studies. 6, 1972, pp. 181-188, Denis M. Murphy: Poor Robin and Shrewd Ben: Hawthorne's Kinsman. In: Studies in Short Fiction. 15, 1978, pp. 185-190. In his presentation, Freese also refers to these comparative studies.

- ↑ See Peter Freese: On Difficulties in Growing Up: American Stories of Initiation from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Joyce Carol Oates. P. 220.

- ↑ Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives. P. 23. See also Peter Freese: On Difficulties in Growing Up: American Stories of Initiation from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Joyce Carol Oates. P. 220.

- ↑ See Peter Freese: On Difficulties in Growing Up: American Stories of Initiation from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Joyce Carol Oates. P. 210 f.

- ↑ See the information and references in Peter Freese: Robin and his many relatives. P. 23 f., Peter Freese: On the difficulties of growing up: American stories of initiation from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Joyce Carol Oates. Pp. 210–213, as well as very detailed Peter Freese: Text 1 and 2: Nathaniel Hawthorne, "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," and Benjamin Franklin, "Arriving in Philadelphia". Pp. 91-105 and 131-149.